Philip Haigh considers the viability of reopening a rail route between Bangor, Caernarfon and Afon Wen.

Rail travel in West Wales is very limited.

Philip Haigh considers the viability of reopening a rail route between Bangor, Caernarfon and Afon Wen.

Rail travel in West Wales is very limited.

In broad terms, the country has three routes running west. The northern one runs along the coast through Bangor to serve Holyhead on Anglesey.

The central route runs from Shrewsbury in England to Machynlleth, and then branches north to Pwllheli and south to Aberystwyth.

Finally, the southern route runs through Newport, Cardiff, Swansea and Carmarthen before branching out to Fishguard Harbour, Milford Haven and Pembroke Dock. In essence, the trio of routes form a back-to-front ‘E’.

To travel by rail between the termini of these three branches requires a passenger to head east to use the Marches route between Newport, Shrewsbury and Chester, which lies largely in England.

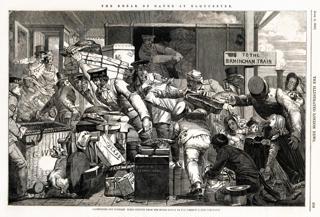

Until 1965, British Rail’s Western Region ran between Carmarthen and Aberystwyth. In North Wales, services lasted between Bangor and Caernarfon until 1970, and between Caernarfon and Afon Wen until 1964. Had they remained, the reverse ‘E’ of today would be a figure ‘8’.

The missing links come under the microscope from time to time, because the Welsh government wants to make it easier for people to travel without using cars.

Reopening rail routes is not easy or quick. You need only look at the time it’s taking to return trains to Portishead, where it’s a pretty simple job of reopening 3.4 miles of line with the old track still in place.

It’s much more complicated in Wales, as a new report from AtkinsRéalis shows in looking at the old route between Bangor and Afon Wen.

Between the two sits Caernarfon as the only settlement of any note, with a population of around 10,000.

It has a railway in the shape of the Welsh Highland line that runs through Snowdonia to Porthmadog. This shares the trackbed of the former main line as far as Dinas, where the Welsh Highland Railway’s narrow gauge tracks bear east along their original alignment, while the former trackbed heads south towards Afon Wen.

Within Caernarfon itself, the old railway now bears road traffic. The rail tunnel under Castle Square is now a road, while a car park sits on what was the station’s southern throat. Morrisons supermarket sits on the former station site and its petrol station on the northern throat.

This line through and under the town centre was the last part of the overall line to open (in 1870). The northern section from Bangor opened in 1852, while the southern section saw trains from 1867.

Caernarfon clearly posed challenges for the London and North Western Railway’s engineers. Their route’s dedication now to road traffic gives today’s planners plenty of headaches, too.

The answer from AtkinsRéalis is tram-trains - similar to the Class 398s that Transport for Wales is testing for services on the Core Valley Lines in South Wales.

Such units can run as trains on segregated tracks with railway signalling, or they can run as trams sharing public roads with car, vans, buses and lorries in a ‘drive on sight’ mode.

AtkinsRéalis suggests two options to run past Morrisons on its seaward side. Its preferred option needs the petrol station demolished. The other needs sea defences built outwards, so that tracks can bypass the petrol station.

A third option swings the new route off the old trackbed to run along the main northern approach road into Caernarfon, before swinging back through Balaclava Car Park and on towards the town centre tunnel.

Even Caernarfon Tunnel is not easy. The LNWR built it for a double-track railway, but today’s road sits higher than yesterday’s rail and so it’s likely to need its road dug out and down to accommodate tram-trains.

Then there’s the WHR station that sits just beyond the southern portal. It opened in 1997, with its modern building following in 2018.

AtkinsRéalis considered using a mixed-gauge railway, but reckoned this plan would not meet with approval from the Office of Rail and Road (ORR).

Its alternative is sharing St Helens Road with traffic. But this isn’t easy either. It would likely cut the road down to a single lane, so needing traffic lights to control two-way vehicle flow.

Heading further south to Dinas comes with the challenge of incorporating the WHR’s track with that needed for tram-trains, while maintaining the cycle path that also occupies the old LNWR trackbed.

Trams and cyclists have long had an uneasy relationship. Where they mix, tramways use rails with a groove that accommodates the flanges of tram wheels. This groove can catch and trap the wheels of a bicycle, which can cause accidents.

And that’s with trams that usually have a narrow wheel flange which minimises the width of the groove. Heavy rail vehicles have wider flanges, known as the P8 wheel profile, which demands a wider groove.

Therefore, AtkinsRéalis has tried to minimise the amount of on-street running, while also suggesting that rubber gap fillers could be used to reduce the risks caused by wider grooves.

But back to the route. Between Caernarfon and Bangor sit Vaynol Tunnels, which comprise twin bores that are 455 metres long. The tunnels pierce a steep hill, making them the only realistic option for tram-trains. However, they’re occupied by businesses which would need to be moved.

A small industrial estate sits on the northern end of the tunnels, and then a water works that would need a new alignment around them.

The old alignment drops steeply to meet the North Wales Main Line at what was Menai Bridge station. It runs parallel with today’s open line for around 1,000 metres, but it sits ten metres higher at the point the two converge near Britannia Cottages.

Any future line will need to be even steeper, because it must cross the A55 dual-carriageway as that road approaches the top deck of Britannia Bridge. AtkinsRéalis suggests a 70-metre bridge if the old alignment is kept, or shorter 50-metre spans if the new route diverts around the water works.

Planners must also develop the best way of linking new and old lines together.

Today’s layout around Menai Bridge has a twin-track line approaching from Bangor to a crossover of two sets of points. This takes trains onto the single line that crosses Britannia Bridge when both sets of points sit reversed.

When sitting normally, the points in the Down Main (westbound) lead towards a sand drag. This arrangement protects the single line from trains running away westwards.

The simplest arrangement would be to place the junction for Caernarfon on the single-track section, with trap points to protect the main line from movements from the branch. However, this results in a steep gradient on and off the branch line.

Planners could replace the sand drag with a connection straight onto the line towards Caernarfon. A second crossover would be placed a little to the east to allow trains from Caernarfon to reach the Up Main (eastbound) line.

Both options need the branch clear before a train for Caernarfon can leave the main line, potentially causing congestion. It might be better to have the junction closer to Menai Bridge, to give a gentler gradient onto the branch and give space for a passing loop to relieve main line congestion. But this needs more trackwork and thus more money.

At the other end of the line, Afon Wen sits firmly in the ‘blink and you’d miss it’ category. It was never much more than a remote railway junction, and when the junction closed, the station’s reason for existing went with it.

The old junction faced east towards Porthmadog. Passengers for Pwllheli had to change to a westbound service at Afon Wen.

If the Welsh government takes forward AtkinsRéalis’ proposal, it would build a triangular junction letting trains from Caernarfon turn west for Pwllheli or east for Porthmadog. Loops on each of the new chords at Afon Wen would allow for traffic regulation without blocking the single line. There is no need for a station at Afon Wen.

This latest report considers only the physical obstacles in the way of reopening. It hasn’t carried out a timetabling study.

However, it notes that journey times between Bangor and Afon Wen in the early 1960s were around 1hr 15mins, with 13 intermediate stations.

AtkinsRéalis proposes eight stations (Parc Menai, Y Felinheli, Caernarfon, Dinas, Groeslon, Penygroes, Bryncir and Chwilog). It reckons a future service should be quicker, but suggests that the final timetable depends on the proportion of light and heavy rail running, with their respective 45mph and 60mph speed limits if stock similar to Class 398s works.

Those ‘398s’ draw their power from 25kV AC electrification or batteries. AtkinsRéalis does not delve into power supplies, but suggests that there may be sections of route for which 25kV overhead line equipment is not feasible.

Reopening the line will, without doubt, make it quicker to reach towns such as Pwllheli and Porthmadog by rail from North West England. It can draw the communities along Wales’ north and west coasts closer together. It’s a vital link in forming that ‘8’ from the reverse ‘E’.

Yet it’s a big leap between that and having a viable case for the money needed to reopen the line, even using tram-trains as a cheaper option.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.