The story of how we arrived at standard gauge, and how it’s anything but standard across the world.

Just how irritating is it when you find you have the wrong phone charging cable?

The story of how we arrived at standard gauge, and how it’s anything but standard across the world.

Just how irritating is it when you find you have the wrong phone charging cable?

Such are the results of ‘format wars’. But the problem is not new.

When the railways started out, there was no such thing as standard gauge. Indeed, early waggonways used a variety of track widths, largely somewhere between 4ft and 5ft.

That made sense if you were using horses to haul wagons, because the motive power could fit between the rails (although sadly the old story that ‘standard gauge’ derives directly from Roman carts can probably never be proven!).

What is true is that railway pioneer George Stephenson came out of such a world, where these gauges were common.

He favoured 4ft 8.5in. And given that Stephenson had such an impact on the development of early railways, including both the Stockton & Darlington and Liverpool & Manchester, it was natural that such a gauge would find favour.

But it wasn’t universal.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel is perhaps one of history’s most ambitious engineers. Rather than copy Stephenson, he specified a gauge of 7ft 0.25in for his Great Western Railway, built from the 1830s. The extra 0.25in was added to avoid clearance problems - in a similar process to how the extra 0.5in was added to the original ‘Stephenson gauge’.

As Network Rail records controller John Page said in 2021: “Brunel was the one to suggest a new gauge for a new technology - to leave the horse and cart behind.”

The GWR’s engineer argued that this offered more comfort, greater capacity, and better stability at higher speeds. There is evidence of all that - reports of 80mph running on his broad gauge are fairly common.

Yet, the broad gauge ending up losing what became known as the ‘gauge wars’.

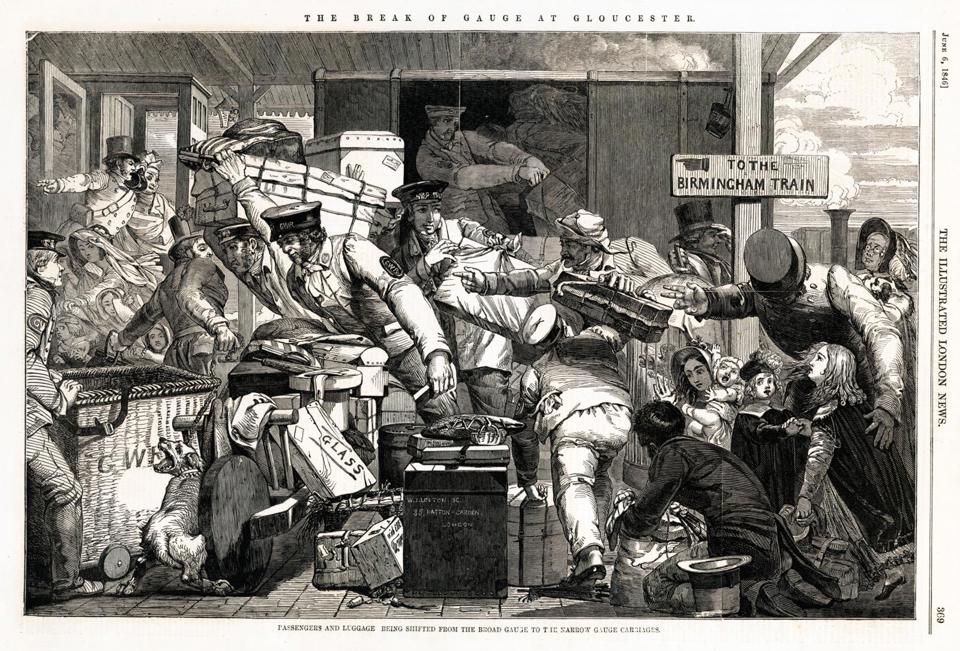

The problem was the same as with any format war - incompatibility. Passengers had to change trains (and goods had to be transhipped) wherever there was a ‘break of gauge’. The logistics were horrendous. What’s more, broad gauge was mainly confined to south-west England and parts of Wales.

In 1845, a Royal Commission was set up to look at the issue.

As a result, 4ft 8.5in was made the ‘standard gauge’ in Great Britain, with 5ft 3in named as the standard for Ireland.

The commissioners did not mandate that the GWR would have to convert, but even so, the future was clear - and the last of the GWR changed over in 1892.

Brian Whitney, a Network Rail track specialist, said in 2021: “Was it the right thing? I don’t think I know. It was that the majority rules, almost, in the mid-1800s.”

Given the UK’s (and the Stephensons’) early role in spreading railways, standard gauge was increasingly adopted around the world.

But that does not make it universal, even taking into account narrow-gauge lines. Russia adopted 5ft, Australia and Ireland both use 5ft 3in, the Indian subcontinent and parts of South America run on 5ft 6in… and the Nazis proposed 3m.

At nearly 10ft, that would have been even bigger than Brunel’s broad gauge… but it was never built.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.