You certainly can’t fault Mark Carne for his vision of a British railway system transformed by digital technology. He believes it would not only create the extra capacity we so desperately need, but also bring a major safety premium.

Carne’s vision is big, bold and quite breathtaking. And in his first year at Network Rail, he has firmly grasped the most uncomfortable nettle with tremendous enthusiasm.

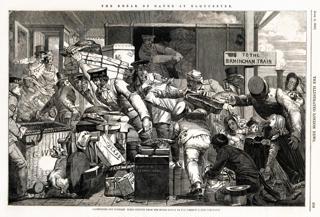

On a railway which in many places still relies on Victorian lever frames in traditional signal boxes to control traffic, with semaphore signals worked by wires and gravity and points switched by long rodding runs of mechanical linkages, there’s certainly plenty of room for modernisation. It’s no exaggeration to say that the oil lamp isn’t long gone on our main lines.

And don’t forget, you still find signalboxes in some surprising places - even in places such as Stockport as a result of the pre-Pendolino West Coast Route Modernisation’s problems!

Even where we do have latter-day multiple aspect colour light signalling, Carne refers to these as “coloured lights on sticks”. And he is by no means the first to do that. I distinctly recall Sea Containers top man Jim Sherwood (well known for his ascerbic tongue) scathingly using the same description at the launch of Great North Eastern Railway in 1996! A mere 18 years ago.

“And if that coloured light stays red,” Sherwood went on, rather sneeringly, “the driver has to climb out of his cab, down onto the track, and use a telephone to talk to the signalman.”

This all speaks of the slow pace of change - as well as the practical difficulties - of upgrading signalling systems. Especially when you have to carry on using an increasingly busy railway at the same time.

So yes, Carne is ‘on the case’ about digital technology. His argument is entirely logical, too. “Look at air traffic control in the UK,” he says. “A few years ago, under the old analogue system, capacity reached a plateau at around 300,000 movements. Once the new system was introducd, it brought vast extra capacity - a 61% increase. We need to do the same thing with the railway.”

So, what precisely does he mean by ‘digital railway?’ Surprisingly, for an infrastructure owner that has been criticised consistently for not appreciating customer needs, that’s where he starts (not with train operations). He believes existing capacity can be boosted by maybe 40%.

“The digital railway is where we use digital technology first and foremost to change the customer experience,” he begins. “So, there’s better information to customers standing on platforms. At the moment we know we can do better about providing information.

“There are also better ways of providing them with means of buying tickets or buying access to trains. Do we even need tickets in the future? We can do that digitally.

“We can also improve communications and connectivity when they are on the trains - and I’m talking now about the railway industry as a whole. For our part, we are already making strides to use digital technology to change the way our workforce interacts with the railway.”

Some of this is pretty obvious stuff involving non-intrusive inspections using digitally equipped trains as well as helicopters - NR uses two modern turbine machines bristling with technology.

“Using these smart trains, we can provide down-the-wire information to people on the track, live when they are there, completely changing the way we work,” explains Carne.

“Then, of course, you’ve already mentioned digital control of trains - or in-cab signalling. This is a huge transformational opportunity - the biggest change in the railway in many generations.”

Warming to his subject, Carne extols the operational and safety benefits that in-cab signalling would bring - chiefly by eliminating not only physical constraints but also dangerous working environments.

“If we move to ETCS, we also remove the need to maintain all of this equipment on the line, so we have a safer track and more reliable railway. This would then be cheaper - we would be able to run more and faster trains that are closer together.

“They would also be more environmentally acceptable trains because they won’t be stopping and starting at red lights - they will just be slowing down and speeding up again. In terms of the overall passenger experience I think it can be a really major step change, but at the moment the programme to roll that out across the network is a very long one - many decades.

“This means that for those many decades we will be running mixed signalling across the network, which is something I also think we should have a look at. So we must set that out as an option that can then be considered by those who ultimately decide how much money should be invested in the railway. At the end of the day, that is a decision for governments.”

Therein we run headlong into one of the big dilemmas of Carne’s thinking. You can’t fault his logic in setting out either the benefits of digital control, or the disbenefits of taking half a century to install it. But at a time of escalating public spending cuts, is it feasible to think this is ever going to happen?

It is a massive undertaking - because Carne is actually talking about getting this job done by 2028-ish. That’s right, eliminating every trackside signal and moving to in-cab control within about 15 years.

To put that into context, current thinking on ETCS/ERTMS envisages a start made in the mid-2020s with completion by around 2062. Each extension would be provided as existing signalling schemes come up for renewal.

Again, it’s hard to argue with Carne’s logic that taking over 30 years to fit ETCS isn’t sensible, as the technology will have completely changed by the time the job is finished. And yet, as he implies, it’s a big and expensive decision for Government to have to take - and that’s before you even consider whether NR is culturally and managerially capable, with the right skills, to be ready for such an enormous task? And in any case, is it definitely the right answer?

“I’m not saying that it’s the right answer yet,” he replies. “I don’t think we have done the work to say that it’s definitely the right answer - but if we don’t do the work to actually consider it, then we will never know. So let’s do that work, let’s lay it out as an option. I think it’s a very exciting opportunity for the railway as a whole.”

There’s no doubt, Carne has absolutely bought into ETCS, which he clearly believes must come - and must come soon. The capacity problems are just piling up, he says.

“ETCS won’t apply in all cases and so we will still need to invest in new railways, like HS2,” he says.

“But for our complex urban railway systems, particularly London and the South East, Wessex (especially coming into Waterloo), Victoria and around Manchester and Edinburgh, there is a lot of opportunity to get many more trains on our existing network.

“The prize includes bi-directional running at basically no cost, plus a huge increase in flexibility in the railway. Reliability will also benefit, given that 10% of our current primary train delays are a result of signalling failures. We’d see less construction, less pouring of new concrete, more limited building of new railway lines, because we will be using the existing network much more intensively.

“Also, let’s not forget that 80% of our SPADs are caused by drivers either not seeing a signal properly or seeing it in a maze of other signalling, or through inattention. So there’s a significant opportunity to improve safety there, too.

“Plus, we will have managed to significantly reduce the number of people we actually have to put out on track, in order to fit or install or maintain this stuff.”

Carne’s vision means scrapping the existing ETCS aspiration of rolling it out incrementally, as various resignalling schemes become due.

“So do we want those huge cost and environmental benefits and faster running? I look at this and ask ‘what is not to like about this, why are we not doing this faster?’ Yes, we know our existing signalling is fundamentally very safe and pretty reliable, and has been perfectly capable of handling the kind of capacity that we have had on the railway over the last few years - but it’s reaching its limit.

“Our railway in certain areas is full and if we are going to make the step change in capacity that we need, we need to think about different ways of controlling trains. Our existing rollout plan for ETCS is based on replacing existing signalling when it reaches the end of its service life. That way we will end up with very fragmented deployment of ETCS, with little bits and pieces of it all over the network over the next 50 years, but not necessarily connected up.

“Because of that, you have to invest in kit on the trains, because at some point in time the train will run over a bit of ETCS railway - so you’ll get the cost but you won’t get any of the other major benefits.

“So, by 2024, two-thirds of our trains would have been ETCS-enabled, but only about 10% of the track. This is a sub-economic optimisation of the opportunity for digital railway. What would it take to actually do something dramatically different?”

Carne stops and reflects for a moment, perhaps aware that his zeal for the principle outstrips the finance, skill, and even will to bite off such a huge job and then hope it can be chewed.

He continues: “This isn’t a plan, by the way. I want to be very clear about this - this isn’t a plan, I call this is a vision. That is to say, I am asking what would it take for us to deliver a complete, national integrated railway.”

Carne has set up a Digital Railway Group, led by Network Rail Group Asset Management Director Jerry England, to come up with some answers over the next two years.

“We need to have those answers within two years - before we have to submit the Initial Industry Plan for CP6 and CP7. We must identify all the barriers that we would have to overcome in order to achieve that kind of programme and let’s see if we can develop an alternative for Britain’s railways for investment in the next ten years.”

But who is going to pay for this? Surely it will mean operators having to shell out for equipment on trains that might lie unused for years? Neither rolling stock companies nor train operators nor the DfT (especially the Treasury) will wear that.

“You have identified one of the challenges,” he concedes. “But I don’t believe that is the sort of challenge which actually stops us - we can overcome that kind of challenge.

“We don’t currently have a supply chain capable of delivering this sort of change programme - we don’t have enough people with the skills to do it. These are plenty of challenges we have to overcome, but I honestly don’t think any of them are insurmountable.

“If the prize is big enough for the railway as a whole, then one of the hurdles we have to overcome is how we distribute the benefits in such a way that they compensate for the additional cost that some operators will incur.”

But won’t NR’s reclassification last September as part of the public debt hamper such a potentially massive investment commitment? NR is already under scrutiny by the Rail Regulator and DfT for the way electrification costs seem to be shooting up - surely there’s no way the Treasury will wear this?

“Well, on one level, it’s really a statistical reclassification of the debt - so it may mean very little,” he says (although I’m not sure I share his optimism).

“We are working with Treasury and the DfT to actually describe the way we will now work with Government. They have been clear that this has been a reclassification of debt - it was not a signal to change the way Network Rail operates with Government. So we are trying to describe the way we will operate in this new world, and to enable Network Rail to continue to operate in much the same way that it does today.

“But we also recognise - and I certainly recognise - that there will be different levels of scrutiny. And, by the way, I welcome that… I welcome the transparency we should operate in because I think it’s absolutely right that customers and taxpayers should know how we make the choices that we make around investment in the railway.

“But if we don’t deliver and we don’t perform, then the Government has the means in its control now to directly influence us in a way which it couldn’t do in the previous structure.”

Precisely! And surely that’s inevitable? Experience tells us that politicians simply cannot resist meddling with railways - either with or without their officials or the help of the Treasury! I’m surprised that Carne disagrees.

“I don’t think it’s inevitable actually, because I think that politicians also know that running the railway is really difficult - really tough - and they are quite happy that there is a team of professionals doing it. I think as long as they are seen to be doing a good job, they will be allowed to do so.”

Hmm. I can almost sense experienced railway managers who have had to fend off precisely such meddling shaking their heads and wondering if Carne is not being more than a little naïve?

So after the next election you aren’t worried that the Treasury will clamp down on NR’s spending, as it tries to implement what respected economists have described as “colossal” cuts?

“I think it’s absolutely right that the country as a whole, represented by the Treasury, should make decisions about where it wants to spend money on public services,” he says.

“And the railway should not be fearful of being prepared to compete against any other form of public service for finance. Governments face choices as to whether we build more hospitals or more railways or more schools, and we shouldn’t see that as a threat. We should just be prepared to make the case for investment in railways in a better way than we have had to do it in the past.”

Doesn’t this reclassification of debt, giving the Secretary of State major new powers, render the members to whom NR is allegedly and theoretically answerable to (as a proxy for shareholders) redundant?

“No,” says Carne, firmly and without hesitation. “To repeat - this retreatment of debt has not changed the governance structure of the company fundamentally, so there is no intention to change either the board structure or the member structure.”

Does reclassification change NR’s relationship with the Office of Rail Regulation?

Again, Carne is ‘glass half-full’. He just won’t see a downside.

“No, it doesn’t change that either, because we operate in a regulatory regime where we have defined outputs defined by government and regulator. With those outputs set, we are left to decide how best to achieve those outputs and that regulatory regime remains the same. So no - reclassification doesn’t fundamentally change things actually.”

Well, perhaps not in principle. But if NR misses a wide range of its output targets, I can see this becoming a very hot potato. There’s a big difference between principle and actuality.

Carne has a way of seeing good in all areas - which is not a bad thing in principle, but I do wonder if he is either turning a Nelsonian blind eye to some issues, or whether he just isn’t seeing some unpleasant truths.

I’m fairly sure I’ll get the ‘party line’ on my next question, but I do have to ask it… what does he think of industry leadership? We have the Rail Delivery Group, the Rail Supply Group, the High Speed Leaders Group - there has traditionally been a shortage of leaders in the privatised railway and a reluctance to take any position, on anything. Now we seem to be tripping over strategic leaders, all with their own agendas and views.

Carne replies: “Yes, I’ve heard you say this in one of your previous Comment pieces. It is an industry that does have a proliferation of industry bodies, there’s no doubt about it.

“But I think RDG plays an absolutely critical role in pulling together the chief executives of the train operating companies, the freight operating companies and Network Rail.”

Like other leading figures, Carne has ‘the script’ clearly to hand. He talks of suppliers being represented in RDG sub-groups and that the RSG now exists. Like everyone else, he skates over the fact that if suppliers were properly involved at RDG, a separate Rail Supply Group would not be needed.

“We want to work very closely with the RSG. I met with RSG head Terence Watson, of Alstom, this morning, so we are working very closely together with RSG. This idea that there is some sort of schism in the industry, I don’t subscribe to it.”

In an industry too often characterised by there being as many opinions in the room as there are people, there’s an astonishing level of agreement nowadays on this subject - even to the words actually used by top executives when you ask them about it! It’s not the sort of consensus normally found and so it’s going to be interesting to see how this develops over time.

We move on to performance. I ask Carne if he thinks that the Public Performance Measure for punctuality is the most appropriate measure of how well an increasingly congested railway is serving its customers? The Tube uses a very different system that measures reliability rather than timekeeping (see panel, page 50). Wouldn’t this be better?

And a crammed railway is only ever going to seem punctual if recovery times are manipulated - which is exactly what happens, of course. Doesn’t this at least blunt PPM, if not render it increasingly meaningless?

“Yes, you could always argue that there are definitely flaws in the way that PPM is measured, and there are undoubtedly many who would argue that there are better measures of assessing overall reliability. But the difficulty is that as soon you change the method of measure then people will accuse you of massaging the numbers.”

He’s right about that. There would be a political and media firestorm whose narrative would be that the railway is trying to massage the numbers because it can’t run trains to time, so it’s looking for another, less inflammatory way to measure performance. Just like when the Government switched from the Retail Price Index to the Consumer Price Index to measure inflation. The thing is - it bit the bullet and made the switch because it felt it was right, despite the criticism. Shouldn’t the railway be equally bold?

“PPM is still the prime measure and for me there is no doubt that we have to move to a right time railway way of thinking, both at the top level and at the Network Rail perspective,” says Carne.

“As the railway becomes more congested, these tiny differences in train paths and in train sectional running times create these interface issues within the network which then back up and create all sorts of problems.

“It’s becoming more and more critical that we focus on the very small deviations to the path and that we relentlessly strive to improve performance. That’s a joint effort with the TOCs, making sure that dwell times are adhered to and making sure that the trains then actually deliver the sectional running times - and stick to them. There’s no doubt at all that there’s still a lot we can still do to improve.”

What’s NR’s view and position on HS2 at the moment?

“We are very supportive of HS2,” says Carne. “The West Coast Main Line is the busiest mixed use railway line in Europe, and without major, further investment in capacity we are going to really, significantly impede the economic growth of the country. So I think that HS2 is a very necessary investment.

“Yes, it is a huge step - but a very necessary one. Beyond that, I think that HS3 also shows commitment to continued new investment in railways, particularly in the North.

“I am also very excited about the Northern Hub and the benefits that’s going to give to passengers in and around Manchester and the North in the next five years. It’s exciting that we are now thinking beyond that and asking ‘what are the next big steps that we could take to improve services in the North?’”

He’s right about that - and the changes in northern mindset following the Scottish referendum have led to a rising groundswell of opinion for more devolved regional powers, with transport high on the list of northern priorities. Neither Government nor NR can ignore this. Change is now inevitable.

Carne is also very keen to talk about NR’s people and skills requirements.

“If you look at HS2 or Crossrail, Thames Tideway, Hinckley… there are all these major projects occurring right across the country, so having enough skilled people to tackle these challenges is very important.”

He then says something that may prompt raised eyebrows around the industry, not least considering the ballooning costs and slow progress on electrification, in particular.

“Because we have such a strong track record in the delivery of these infrastructure projects, we are a very attractive breeding ground for people, some of whom leave. I am very proud that people have confidence and want to come and recruit people from Network Rail. So we have to therefore go out and develop new talent to replace that, and I think we have a tremendous programme of investment in people.

“The training centres we have are second to none. We have just opened a new one in York, we are opening one at Basingstoke very shortly, and we have a marvellous training facility at Westwood, in Coventry. So, our investment in people and developing people is one of the great strengths at Network Rail, and it’s something that I am absolutely committed to continuing to pursue.

“But I also think that this idea of what I call the Digital Railway, and the sort of technical transformation that can occur in the railway, will make the railway seem a much more dynamic and exciting place for young people to be a part of. We are competing against many other industries for the brightest and the best, so we have to think about how we are going to succeed in that market place and attract young people to want to come and join this industry.”

There’s one last aspect I want to drill down on - and that’s Carne’s relentless focus on safety. My worry is that his microscopic focus on fine detail runs the risk of losing sight of the bigger system safety picture.

When you visit the NR offices now, the receptionist self-consciously gives you a little safety lecture that comes down to being told to watch your step, hold the handrails - and if you see a safety risk, please tell us.

It was the same story on the BP Deepwater Horizon production platform off the US coast in 2010. It exploded, killing 11 people, causing massive pollution and costing BP billions of pounds in fines and compensation. The court cases still go on.

My point is this: what many people don’t know is that the night before, a group of BP top executives were on the mainland, preparing to fly out to the rig on the day it actually exploded - to present safety awards focused on watching for slips and trips and holding handrails.

They did ‘small personal safety’ well, but in the pursuit of an end to minor slips and trips, much bigger system risks went unaddressed. Is Carne running the same risk at NR, by making receptionists tell people such as Wolmar and myself effectively not to run in the corridors when we visit his office?

I think I detect a hint of irritation behind the smooth and controlled highly-polished exterior, but if it’s there, it’s only for an instant. I certainly think there’s a soupçon of discomfort. But he smiles again.

“It’s true that there were inspectors on the rig at the time,” he answers carefully. “They weren’t necessarily there to give the awards out - but I think that slightly misrepresents the situation that I am trying to talk about.

“So without wishing to talk specifically about BP and that particular incident - if you think about the waves of improvement that the oil industry (and our industry) has gone through… when you have had a serious accident like Piper Alpha, Clapham, Potters Bar or Ladbroke Grove, what happens is that there is a technical fix.

“People focus on an engineering solution, and that’s embedded in things like the safety cases and safety regulations and so on - so that’s about engineering improvements. But then the next wave is when you start to get into the safety management system: how do we ensure that our people have the right competency and skills to be able to execute their jobs properly?

“But the third wave is all about behaviours - it is about really getting people to change the way they work. The crucially important point is that you have to have all three waves. The danger is when you get to the third wave - the behaviours wave - you must not put all of your focus on that and forget about processes, skills, or engineering accidents. If you don’t have proper focus on all three waves then that is when you start to let the system you describe creep in.

“It is definitely the case, in my view, that in the oil industry there are now a lot of people who have almost forgotten this vital point. We will not be doing that.”

So you have to have all three in a mutually supportive tension? To hold the whole system together and keep it in safe balance?

“You make a very, very good point,” he concedes. “And I am acutely aware of it because when I talk about workforce safety, it’s not because I am not worried about train accidents. Of course I am worried about train accident risk - it’s the most important thing that we have to make sure we get right from a safety perspective.

“That’s why we have very clear plans of how we are going to reduce train accident risk by a further 50% in the next five years.

“But we are also changing our work processes - we are looking at safe systems of work. This is a fundamental change to the way we have controlled work on site in the past - we are making sure that the competencies for safe work leaders can only be held by permanent staff. They now cannot be held by contingent labour, so as you see - we are indeed working on all three elements of the safety journey at the same time.”

So when it’s time to pack his bag and leave NR (in two to three years judging by previous experience), what will he wish to leave behind as his legacy?

“If I felt that the railway was a safer place, that it had a real high performance culture embedded within it, was forward-thinking in terms of technology, and was brave enough and ambitious enough to apply that technology - then I think that would be a pretty good place to sign off.”

- This feature was published in RAIL 764 on 24 December 2014

Anon - 20/08/2015 19:08

That's all well and good... However judging from his comments he is a big benefactor of the massive loss of jobs for people through this scheme.