Download the graphs for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

Jobs, housing and economic growth are a priority across the UK. To achieve this, cities - and their transport infrastructure - matter. Cities are the drivers of innovation and of economic growth and performance - not only today, but also increasingly as our need to compete in the world economy intensifies.

We delude ourselves if we believe that we can opt out of such competition. Our current standard of living is not a birthright. If real wages are to start growing again and if our children are to be better off than we are, we will need to invest to keep up at the top of the value chain and to continue creating the new opportunities that made this relatively small country among the richest in the world.

This means that we must invest in our cities. Not only because 60% of jobs are in cities (which cover less than 10% of our land mass), but also because cities are where innovation and new ideas come to fruition.

Over recent decades, a modern knowledge economy has flourished in our cities, at the heart of dynamic city regions. They have shown how larger centres can generate greater density and higher wages, if supported by good transport systems both for the labour market and for business-to-business access.

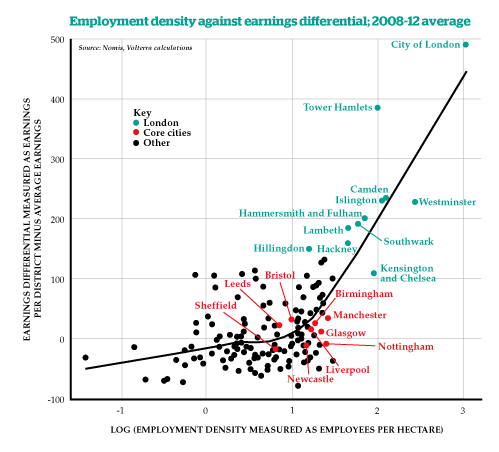

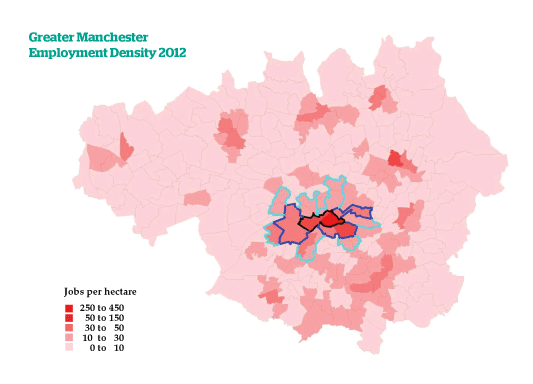

For cities, jobs and productivity are related to density (see diagram, page 22). The diagram compares wage levels and density across the largest local authority districts, and illustrates this curve. The densest and most highly paid districts are all in London, where there is also a high concentration of private sector knowledge-intensive jobs (51% in 2011). The other major cities are all in a middle range of densities, and have not all yet achieved relative wages significantly above the average.

Crucial to the role of a city is the existence of its city centre. This is where the intensity of communication takes place that can generate a successful location. Increasing the scale of such centres enables individual and business specialisation that in turn generates diversity in a city’s offering.

Diversity is related to a city’s ability to attract sufficient density of knowledge-intensive jobs. Work carried out by the Centre for Cities has established this. The cities with higher proportions of knowledge-intensive business services-based jobs (KIBS) also have higher relative earnings for a given density - Newcastle and Nottingham do less well than Birmingham or Manchester, for example. Achieving greater densities needs to go alongside achieving the range of knowledge-intensive roles that are apparent across London, where both wages and densities are highest alongside high proportions of knowledge-intensive roles.

The city advantage rests fundamentally on communications. Cities allow people to get together, exchange ideas, use resources more effectively and be creative. Transport systems make it possible to achieve this, as well as making the wider connections to other experts, to markets, and to wider ideas. Even digital economies

still need physical connections, as Silicon Valley shows.

So the question on which we must focus is how best to enable the range of communications needs that cities require in order to thrive and what the right mix of investments is - particularly in physical transport. A process known as agglomeration drives success in cities. It was first observed in Manchester. As the scale of the labour market increased, so too could its efficiency, with better matching between jobs and people as well as more choice for both employees and employers.

The importance of this has risen in recent decades, with the proportion of two-earner households and the flexibility that this requires. Marketing new ideas between businesses is easier in a larger market, as is generating them in the first place. Facilitating the emergence of new specialisations adds to the diversity and attractiveness of the business centre, and creates positive feedback.

A recent example might be the emergence of King’s Cross as a new business area. Reinvestment in the area’s railway stations, coupled with the high-speed line to the Channel Tunnel, encouraged additional public and private investors - from new offices to St Martin’s School of Art, Kings Place concert hall, the British Library and the Francis Crick research institute. A down-at-heel area once known chiefly for drug addiction and prostitution has been completely transformed.

Creating emerging centres is not a centrally driven process, it relies on integration between development, policy, transport and market forces. We know from cities around the world that devolution and more integrated approaches to investment will secure better infrastructure, unlock growth and create new, locally-determined funding opportunities. Centralised decision-making, on the other hand, means that transport decisions are evaluated independently of their impact on the economy or interaction with other policies, something that astonishes non-economists and even some politicians.

And Britain’s cities are among the least devolved in the world, with very little control over services, funding or borrowing. This constrains their ability to give a clear focus across policies at the local level, to promote sources of competitive advantage in the interests of local and national productivity.

Getting the right mix of investments requires the ability to set priorities and the ability to fulfil them. UK cities currently have little leverage in this, because of the centralised nature of decision-making in this country.

This has been extensively investigated in recent years, by the City Finance Commission and the London Finance Commission, as well as by the Government. The most recent publication was by the City Growth Commission, of which I was a commissioner.

Once again, it has highlighted how the UK is the most centralised of developed economies and how even recent City Deals and Growth Deals have had only very limited impacts on this. They propose that city regions - metros - should have the ability to access greater independence in finance and investment, subject to some selection criteria to show that the city has the requisite skills and tax base.

Appraisal and funding system

A consequence of the UK’s centralised system is that funding for cities comes down a complex set of pipes, with no connections or integration at the city level. A more devolved system could not only take a more coherent view of the investment needs of a city, it could also prioritise on a wider set of criteria than is currently possible. In particular, such criteria can be focused on economic potential and growth as much as on welfare (or user benefits), which is the basis for current spending decision-making in government departments such as the Department for Transport.

The UK’s current appraisal and funding system is based on the assumption that transport investments are made to generate welfare improvements for passengers, rather than to change the economy’s output potential. Where change is only incremental, it may well be reasonable to consider the economy as being independent of transport in this way. However, where there is the potential for structural economic change, accompanied by major spatial change locally and regionally, this is unlikely to provide a sufficiently full view of likely future transport requirements.

Our appraisal system insists on using models in which the past informs assumptions about the future, but the changes experienced at Canary Wharf show that past trends are not, in all circumstances, a useful guide.

This is a very important realisation - it suggests that our current static framework for evaluation, particularly of large-scale and long-term projects, is inappropriate. It will not capture the feedbacks that change the nature of places, even when so-called ‘wider benefits’ are taken into account.

What should be asked is: what constraints exist, how serious are they, and what might relieve them? The further question is to gauge the extent of new opportunities - how they can be accessed, and what investment would make it possible to achieve them.

Localities can recognise and leverage the combinations of factors that create a place and attract variety of investment.

When first opened, Manchester Metrolink beat expectations of ridership and leveraged private investment into Manchester. Reinvestment in St Peter’s Square and in the airport has also resulted from better connectivity secured through the current Metrolink expansion programme. This expansion has been facilitated by a locally-led, risk-based funding programme with a significant proportion of finance secured through borrowings against future farebox returns and local council tax receipts.

Greater Manchester has thus been able to deliver regeneration-led investment projects (such as the Manchester Airport Metrolink extension) that would have performed less favourably under national welfare-based analysis approaches than under the productivity-led analysis and prioritisation used by the Greater Manchester authorities.

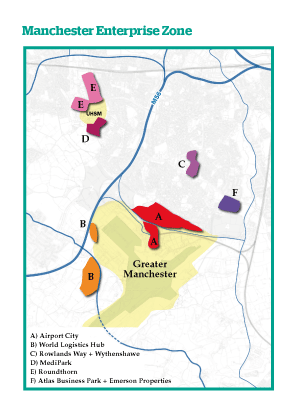

Argent, which led the redevelopment of the land between King’s Cross and St Pancras in London, is now leading the Airport City North development in Manchester - this forms a major component of the Enterprise Zone (see map, right) that has been identified around the only UK airport outside Heathrow with two runways.

Unless we make changes to our evaluation system, the UK will continue to miss out on the potential of its cities. Visionary schemes such as Crossrail, HS2 and the One North proposals rest precisely on their ability to be game-changers for city regions and the whole country. And they require complementary plans to be put in place to allow this to happen.

Strong risk analysis

What we need is a reformed system that looks both at returns on investment and allows these corresponding policies to be put in place. Major investment decisions must be shaped by a more holistic view of cities’ needs - it must start with the growth imperative and then be supported by strong risk analysis, rather than a narrow transport appraisal system that assumes the development of the economy is broadly independent of the transport system.

The proposition is actually fairly simple. Devolution and better transport and land use planning go hand in hand. Both for London and other cities, an integration of land use planning and development with the transport investment is central to economic growth and to future welfare. (Welfare has a particular meaning in economic theory that is narrower than its meaning in normal language.)

Maximising economic potential will require both inter-city and intra-city investments as well as parallel engagement from all cities, from London as well as outside it. Most importantly, the decision process needs to be reconsidered to focus on how payback is to be generated and by whom, so that financing and funding decisions can be aligned.

Maximising economic potential will require the building of dense city centres that can accommodate productive workers in knowledge-intensive firms and sectors. Such firms exist across a whole range of activities - from bio-medical research to 3D printing, as well as accounting and law. But creating dense city centres requires both commuter networks and external networks to access major markets, as well as the planning policies to support development.

A key conclusion is that creating a larger and more effective commuting potential for all the cities outside London should be a priority, as this has been neglected. And given the difference in scale, this suggests that more effective integration of these cities is required. Indeed, this is a key conclusion of One North: A Proposition for an Interconnected North, the One North report prepared in July 2014 by the cities of Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle and Sheffield.

The report concludes: “Our proposition builds on this common perspective and aims to create a North of England that is a powerful and integrated series of economic geographies. This will be a highly interconnected region of thriving cities and towns, providing a valuable counterweight and complement to London and helping to re-balance and deliver growth for the national economy in the decades ahead.”

Links between cities in the North are not as effective as those into London. The fastest link is between London Euston and Milton Keynes, with a journey time of 30 minutes for 50 miles. The distances between Sheffield, Manchester and Leeds are all shorter, with 39 miles between Sheffield and Leeds and between Sheffield and Manchester, and 43 miles between Manchester and Leeds. Yet the quickest trip is between Sheffield and Leeds (40 minutes), while Manchester to either Sheffield or Leeds is nearly an hour! There are also just ten trains between these three pairs of cities in the peak hour (0800-0900), compared with 11 just between Milton Keynes and London.

Devolution will be required to ensure that these elements can be effectively brought together, as well as to prioritise the investments that support growth in a manner that can be responsive to local economic conditions.

A process that focuses more centrally on the economy, through economic entities/geographies and corridors, will prioritise both revenues and output potential, as well as take a risk-reward perspective to investment rather than assume that the future will be like the past.

But a different approach requires an understanding of the mechanisms by which transport can be associated with economic performance. This was explored in High Speed Rail, Transport Investment, and Economic Impact, a 2013 paper for HS2.

It is not enough to observe that trip growth has been associated with economic performance, since correlation is notoriously not causation. Moreover, there is an increasing view that the performance of some cities has already been constrained by a lack of infrastructure of the right type. A focus on growth creation and the role of transport investment challenges our existing system of evaluation and how we think about finance and funding.

So what is to be done?

The focus of evaluation needs to concentrate on revenue and on the wider economic returns generated by major transport investment programmes. Instead of thinking about welfare benefits that do not exist in real money, we should concentrate on those that have direct value. It then follows that we should think about what revenue will not cover, and why there might be a case for such investment. This is where GVA, productivity impacts and returns to the national economy over time come in.

This allows us to consider the capital financing of transport projects in a new way. A project that offers proven, realistic potential to add to jobs and productivity will raise the total sum of taxes generated and present new sources of finance over time. And in due course, there will be continued streams of activity-generating benefits.

By viewing spending priorities in this way, we can break with the constraints of short-term decision-making and spending approaches, to create a virtuous investment and performance that rewards a spirit of entrepreneurialism in our cities. Through this model, of course, welfare benefits will still be represented, as has been shown by the Greater Manchester Transport Fund investment programme, whose components were determined by their GVA potential and refined by the ability to secure social and carbon benefits at a programme level.

Crucially, linking benefits to paybacks, particularly those generated by new economic activity, is done much more easily at a sub-regional or city region level than nationally. Once the assumption that the economy is independent of the transport system is abandoned, then the immediate prior question becomes what the objective of a policy is, so that the relevant benefits can be examined.

Cities and city regions should be able to have a more focused view of their prospects and how best to respond to opportunities. Indeed they will be essential to actually taking advantage of new opportunities. Transport is a necessary but not sufficient condition for success. Cities and their regions will play a key role in ensuring the other conditions are in place, and therefore for maximising the value for money of the overall investment.

Risk analysis is a vital component and should play a much broader role. It must achieve two things. First it must identify the key risks, then it must assess them. A big element of this is to assess where the future could be different from the past and how much needs to change for the future to pay back an investment. A sense of the scale of change, and whether such change has any historical precedent, is enormously valuable in assessing both feasibility and risk.

The risk that we fail to put in place sufficient infrastructure and thus constrain growth needs to be set against the risk that we over-invest. All the evidence suggests that we have historically under-invested, while economic opportunities are currently burgeoning. The need is to free up the ability to invest on the basis of a potential payback in revenue and in output terms.

The current system is not risk based. Implicitly it assumes that all possible productive investments have already been undertaken. The public sector only undertakes those investments which produce other benefits additional to what would otherwise exist. In fact it is very important to recognise that it is impossible to prove such additionality, at least in a real scientific sense. Consider HS2. This is an investment over twenty years at a minimum even if we accelerate the implementation. What will happen in the ‘Do Nothing’ case? Enormous changes in the world economy will occur. The EU might collapse; new but currently unknown technologies will certainly emerge. We can, however, be sure it will be hard to access new opportunities for northern cities and that they will remain small scale. But what is the economic consequence? How severe? Forecasts based on extrapolation cannot answer these questions.

Yet unless you are sure about the do-nothing, it is impossible to be sure about the impact of the do-something. Even less can you be sure if the do-something needs other investments alongside it, in local transport or in skills, to be truly effective. Additionality is an empty concept where long-term change is in prospect. It might have some validity at a small scale or over a short time. But in the case of significant change or over a long time scale it is impossible to use.

Risk analysis is more relevant. Risk analysis must do two things - it must identify the key risks, then it must assess them. A big element of this is to assess where the future could be different from the past, and how much needs to change for the future to pay back an investment. A sense of the scale of change, and whether such change has any historical precedent, is enormously valuable in assessing both feasibility and risk.

Take Crossail, for example. The additional peak capacity created by the scheme is around 80,000 additional people delivered into the central area. The analysis instead assumed that only around 35,000 additional people would arrive, based on both transport, cost and crowding off models. Could the additional output pay for the railway? On what assumptions?

Payback will be larger

Again, some restrictive assumptions about full employment, the size of a productivity differential and the time frame for increasing employment were used and the output and taxes were still sufficient. So the risks are largely on the upside - to the extent that as the rest of the system fills up, payback will be larger, and as new investors are attracted, payback will again be larger.

An approach of this nature would look at investments such as HS2, One North or Crossrail 2 from a rather different perspective. It would be possible to conclude that such investments are necessary because of the risk of constraints that could otherwise emerge, even if we cannot be certain.

There is a highly visible and powerful risk that London and the South East will become still more unbalanced, with regard to the rest of the country.

I have argued here that agglomeration forces are powerful, and it is therefore likely that scale will attract scale. It is not feasible to create an alternative agglomeration in one city, so the most likely strategy to succeed is to connect existing agglomerations together more effectively and then to connect them better to the outside world and to the international gateway of London.

From the analysis of cities with more than one centre, it must be recognised that multi-level agglomerations are harder to grow. However, they do exist in both Germany (the Ruhr) and the Netherlands (Randstad), and close links enable specialisation to become the diversity that drives success and resilience.

This is where it is necessary to begin to think in risk terms, rather than formal and unprovable models based on the past.

Let us assume that better connections between the cities of the North support an additional 5,000 jobs in each of the major cities. This is significant, yet in just the last two years, 13,000 private sector roles have been created in Manchester alone.

Let us also assume that this also raises the employment rate, so that 20% of the jobs go to people who were not previously working. This would narrow the gap on participation rates, but not close it. Using estimates of average output, this generates roughly £15 billion of additional value over a 60-year period, illustrating how a relatively small impact on the number of jobs available can build up over time to a large total, creating output and economic performance that helps pay for it.

Such calculations can and should be challenged. For example, what productivity growth rate should we think about, and how can history inform this? Are such job assumptions too weak, or conversely can they only happen if other investments are made as well, whether in transport or other areas? However, all of these questions can be laid out on a limited number of pieces of paper, so that everyone can understand them.

Most non-economists, including some politicians, are astonished to learn that transport is not considered to be an investment in the economy. They would consider it obvious that a city development plan should go alongside the plan for a new railway and new stations.

And yet it required a taskforce, chaired by Lord Deighton, to make this recommendation as a key element in maximising the benefit of new transport investment, alongside recommendations to review guidance on how we evaluate such major game-changing investments. (In High Speed 2 Get Ready, a 2014 report to the Government by the HS2 Growth Taskforce.)

A previous review of transport evaluation, chaired by Lord Eddington, argued that smaller projects may be more effective. With our current system, that is an inevitable result of an evaluation system that starts from the proposition that the economy and transport can be separated. It also results from greater ability to analyse smaller projects, because more variables can be held constant.

With schemes such as Crossrail, HS2 and the One North proposals, they rest precisely on the ability to change everything, and require plans to be put in place to allow this to happen.

Thus, the proposition (as described earlier) is actually fairly simple - integration of land use planning and development with the transport investment that can pay for them is central to economic growth and to future welfare.

However, the cities and city region authorities will also need a wider structure re-oriented to reflect this. Taking HS2 as an example, its success requires a robust alignment of local and national agencies to realise its potential. This will need a significant shift not only in the prioritisation and investment approaches adopted by agencies such as Network Rail, but also in their planning and funding horizons, so as to ensure that the current arrangements (typically constrained to five-year cycles at present) can be reformed to reflect the 20-year development processes involved in HS2. Only in this way can the UK ensure that its processes do not undermine its potential.

This is not a zero-sum game. If economic growth is somehow predetermined, then both government policy and market pressures will limit debt to GDP ratios. However, devolution and more integrated approaches to investment will make better infrastructure, unlock growth and create the opportunity to pay back debt. In this case there is a distinction between the purposes of borrowing - as growth emerges, then debt amounts can leave ratios unchanged.

The challenge for cities and transport authorities is to ensure that the case for borrowing includes the mechanisms by which it can be paid back.

Finally, the model requires a new paradigm for planning and funding transport across all agencies, national and local, breaking free from five-year funding cycles to truly respond to the long term.

The scale of opportunity and pace of change offered by our cities, acting in a global marketplace, demands this. So too does the national transport framework that will be shaped by programmes such as Crossrail and HS2 that will be delivered through the next ten to 15 years.

A fresh approach to these decisions is essential, to give a strategic focus on how investment is to be paid back, whether by fares, taxes on increased activity, or developer contributions.

- This article draws on Investing in City Regions: the case for long-term investment in transport, November 2014, prepared by Volterra Partners.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.