Read the peer review for this feature.

Read the peer review for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

The number of political organisations shaping and influencing aspects of the railway is increasing. Alongside the Department for Transport, Transport for London, Transport Scotland and the National Assembly for Wales comes Rail North, a new organisation representing 29 local authorities.

West Midlands Rail will follow. Early lobbying is starting for a group to represent the South East outside London. And the South West is a potential candidate in the future. Each one believes its own geographical area deserves special treatment, extra funding and stronger local powers.

Do these bodies make life easier for the railway? Do they make it harder? Or do they merely make it more bureaucratic, adding layers of consultation and more politicians to please or appease?

Will fragmented political influence complicate the contest for limited funds and diminish control by a strategic-thinking national Government that can oversee competing geographical regions intent on boosting their own local agenda at the expense of the greater good? The system in well-funded Scotland is firmly established, while Transport for London wields enormous power in the capital - for more than one person in ten in the UK it is the most significant transport decision-maker.

“Local control has improved London Overground and Merseyrail by any measure you choose,” contends Stephen Joseph, chief executive of the Campaign for Better Transport.

“It has shown that local people take more care with the assets than civil servants in central Government are capable of doing. The benefits are clear and unambiguous.”

But what of the newcomers and the wannabes? The South East argues that it has lost out on rail funding, and deserves more. The home of HS1, Crossrail and Thameslink believes it has a compelling case. Meanwhile the North, still running unloved Pacers and comparatively under-financed for years, finds such claims risible.

In June, Secretary of State for Transport Patrick McLoughlin confirmed £13 billion of government transport infrastructure spending over the next five years to secure improvements in the North. The money includes pressing ahead with HS2.

McLoughlin said he would “progress plans” to “build on the concept” of HS3 for high-speed services linking the main Northern cities, reducing travel times and increasing service frequencies. Major road improvements are also included in the spending, including “looking at” building a road tunnel under the Peak District.

Rail North

Rail North represents an area of just ten million people, but a quarter of the national economy. That is much larger than Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland combined. It is an economy greater than the individual countries of Denmark, Norway or Sweden. Yet it still relies on Pacer rail buses.

The Government says it wants to rebalance the national economy away from the congested South East, and away from a reliance on financial services. To achieve that, the North’s economy would need to grow at a rate faster than the country as a whole.

This new organisation represents 29 local transport authorities. Chaired by Sir Richard Leese, the leader of Manchester City Council, Rail North will be at the heart of a decentralised, devolved railway structure. On March 20, McLoughlin signed a Partnership Agreement for the management of the new Northern and TransPennine Express franchises, which start on April 1 2016. Rail North had already worked with DfT to develop the new franchise specifications.

The agreement includes mechanisms to enable the individual transport authorities to make decisions on changes to their own local rail services, and to make investments in these franchises. It also enables further devolution to take place during the life of the franchises, as the wider nature of political and economic devolution remains far from settled.

Train operators are currently finalising their pitches for the franchises. A preferred bidder will be announced at the end of this year.

Rail North’s strategy differs little from the national perspective in terms of its key messages - improved connectivity and a more coherent and user-friendly network with increased capacity, while ensuring that running costs per passenger fall. It covers 682 stations - just over one in four of the UK’s total.

Rail North is not to be confused with Transport for the North, although many of its members are the same. The latter is currently governed by an interim partnership board of the Department for Transport, Greater Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield, the North East and the Humber, together with Local Enterprise Partnerships, Network Rail, Highways England and HS2 Ltd. If that sounds large and lumbering, it does not even have a leader yet - an independent chairman is promised by the autumn, to spearhead Northern transport policy as a whole.

Rail North does not yet have a managing director either. But by the autumn, it will. In the meantime the guiding light behind it is Merseytravel Chief Executive David Brown.

“I was asked to lead it a year ago,” he says. “It had been a project for about a year and a half before that. At its peak it probably takes me two days a week.”

Brown’s office has possibly the finest view on Merseyside. It’s on the 13th floor of a 13-storey building right next to Liverpool’s Three Graces, overlooking the Mersey. Through one window you look along the former docks and out towards the sea. Through the side window you look across the river to the Cammell Laird shipyard, with the dark hills of North Wales in the distance. Directly below, the Mersey ferry plies its trade.

Brown sits with his back to it all - “so it doesn’t distract me” - as he sets out the philosophy of Rail North.

“Train services are clearly part of the economic growth agenda. The whole Northern Powerhouse thing wasn’t invented when we started looking at how the region’s transport authorities could work more effectively together. But connectivity between our city regions was already seen as a key economic driver.

“In the North, we wanted a greater say in what was important in our rail services. In the past, these had been specified by central government based on limited change - a no-growth scenario. So there was no investment for ten years.

“Getting a structure that gives political oversight on the franchising process and the content of the specifications was important.”

Will passengers notice any difference from this additional layer of regional accountability? Brown says so.

Will passengers notice any difference from this additional layer of regional accountability? Brown says so.

“Last year we produced a rail strategy for the North which was bought into by all the local transport authorities, which is no mean feat. We influenced the franchise specification and used our own market research and feedback from businesses. Then we consulted last summer and got 21,000 responses on that. It is the biggest consultation outside HS2.

“It means that what the customer wants is reflected in the tender documents - more trains, better trains, new services on Sundays, and most importantly new trains. We will get rid of Pacers.

“So actually, what passengers told us they wanted will be delivered. As a timeline this is incredibly fast. We asked customers last year what they wanted, and in three years’ time they will see new trains arriving.”

Would this have happened if the process was run entirely by the Department for Transport?

“No. I’m absolutely clear on that. We have brought a Northern view of what is important. But not just a vague wish list - it has been backed by rational, economic, operational and cost:benefit analysis.

“For example, Cumbria has been saying for years that its visitor economy needs Sunday services on the Cumbrian Coast Line. It has also said that the train times for Sellafield staff don’t meet the shift patterns of a very large local employer. Cumbria wants more trains across to Newcastle. All of that is in the franchise ITT - that has never been delivered before.”

Rail North is a company limited by guarantee. Each of the 29 local transport authorities nominates a politician as their representative. These then nominate 11 directors from among their number. They set the strategic direction.

In due course, there will be a small staff (probably four people) who will work from Leeds alongside staff from the DfT, and speak to the Department with a single Northern voice. Only one authority invited to join declined to do so - Derby has just two Northern services a day, and felt its role was too peripheral.

“A year ago, the Department for Transport was sceptical that we could work together,” admits Brown. “But they have all signed up to the association, they have all paid their membership fees, they have all come together to elect directors, and they have all signed up to the strategy.

“This is not about the North coming up with a load of train spotting ambitions - this is about business, it’s about growing services. As authorities our funding is declining year on year, so we have to be very businesslike about this.

“Our support is cross-party. The 11 directors come from completely different ends of the political spectrum, but they all want the same thing. The Chancellor is hearing a consistent message,” he concludes.

“Manchester is stealing a march on other areas,” contends Alex Hynes, managing director of Northern Rail. “It is booming. It is the principal counterbalance to London. Greater Manchester ‘gets’ working together - the Tories, Labour and Liberal Democrats each control areas, but have to put their differences to one side. They have been very successful at pushing devolution forward.

“You’ve seen some of this happen in London, Wales and Scotland, where it has delivered benefits for rail. Arguably the North has lost out from not having devolved powers so far, and we want a slice of the action here.”

Merseytravel’s Brown notes: “People in the North realise that if they get a high-quality service they will have to pay more for it. That can’t apply to some routes, of course, but it can to the big flows. Our agreement states that once the base has been let, any revenue generated by fares going up by more than inflation, or cost reduction that we have identified, gets retained in the North.”

Brown recognises that whatever solutions are put forward by Rail North, they must embrace cost reductions. In the past, he says, that was done by putting up fares and reducing services. The alternative is to grow the market, and ensure that better service quality attracts people willing to pay higher fares on those routes, which justify them. As Northern, TransPennine and Merseyrail have all enjoyed steady growth during a period of no investment and no new services, he feels that is achievable.

“We have specified that the cost per passenger must fall because the subsidy levels are going to decline. We are trying to get more passengers to offset that. We know we can fill more trains. More people want to get on our trains for work and play and that is good for our cities.”

Hynes welcomes Rail North’s involvement and can see the benefits of being answerable to the new umbrella organisation:

“Rail North will have people in the Department for Transport team evaluating the bids. The new franchises will be co-managed with them, so even the DfT management people will be based in the north of England, and not in London.

“At the moment TransPennine has a contract with the DfT alone. I have a contract with the DfT and with the five Passenger Transport Executives, although my franchise and TransPennine are mutually inter-dependent. Recent changes by TransPennine were all about chasing the money across the Pennines and between Manchester Airport and Scotland. And in some cases that led to a reduction in the local service. Clearly those planning decisions will be more joined-up in the future, as the franchises will be managed together and not separately.

“The other benefit is that the five PTEs are very focused on pursuing their own local agendas - why wouldn’t they be? So there is a tension between what Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds and Newcastle want.

“The other benefit is that the five PTEs are very focused on pursuing their own local agendas - why wouldn’t they be? So there is a tension between what Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds and Newcastle want.

“In future, under Rail North, all the 29 transport authorities in the North will come together and be forced to speak with one voice. That is one reason why Rail North has been so successful in influencing the ITT for Northern, because they have lobbied government coherently as one group.

“Until Rail North there was no coherent view across the region. Now the northern transport authorities have to get in a dark room and work out how to function together, making compromises. To central government it means the North presents a much more joined-up view, which has to be a good thing.”

Hynes does not think that will necessarily result in an easier or less bureaucratic ride for him. But he does see it leading to more money in the rail pot.

“Politicians like spending money on things they control. When Rail North has focus on both franchises, I think it will want to spend more money on them.

“For example, Greater Manchester has been spending its trans-port money on building a fantastic tram network. So it has not been spending loads of money working with us on improving rail services and stations in Greater Manchester. As a result, station quality is pretty basic. West Yorkshire doesn’t have a tram, so it has spent a lot of money with us, upgrading the local network. And it shows.”

David Brown does not see Transport for London as the role model for devolved transport authorities.

“I spent time understanding what Transport Scotland has done with letting out franchising. It has a lot of local transport authorities across Scotland, so is probably more akin to what Rail North is trying to achieve, rather than TfL. Because we cover a very big geography, at the moment we are just looking at rail franchising.”

So what’s in it for his employer, Merseytravel, which releases Brown for up to two days a week? The Merseyrail franchise represents around 5% of the total northern rail network, and is not part of Rail North’s two-franchise remit.

“We have a clear long-term strategy for rail on Merseyside, with a long time left on our current concession. We have interesting investment coming in new rolling stock, station improvement plans and extensions to the system. So a lot of the experience we have here is feeding into Rail North. On our local city lines, we are looking to get a similar quality to what we already receive from Merseyrail. At the moment Northern is not as good, not as frequent, and the customer service is not as good. For us, we are hoping to get a raised standard.

“We spent a lot of time making the wider economic case for the replacement of Pacers. All customers said to us that we needed more trains and better trains. Our train stock was old and decrepit. That became a mantra for us, focused on Pacers. A lot of those trains are full. But there is actually no financial case within the railway for replacing the Pacers with anything - they are so cheap.

“The case had to be made in a wider way. It was about the wider economic benefit, and that is where - as a bigger Rail North - we could more effectively influence MPs and the Department. And it worked. The result is the tender specification including a minimum of 120 new vehicles. We are very clear about that being a minimum. And we are very clear that these are new-build - we do not want refurbished Vivarail Tube trains. I have seen quotes from the DfT, also saying that “new” really does mean new, not second-hand from anywhere else.

“And they have to be diesel-powered. The growth potential in the North requires that, because the electrification programme is not going to deliver here. Electrification of TransPennine has been moved back, so there will be no cascade of suitable trains. We cannot wait for that to happen.”

Brown was speaking in the aftermath of a remarkable weekend for the transport system on Merseyside. One million people had attended a celebration to mark 175 years of the shipping line Cunard. Although the waterfront event happened over three days, most visitors were concentrated in a two-hour period on a Bank Holiday Monday.

It was one of the largest spectator events ever held in a single location in the UK. The Olympics were bigger, but spread over a fortnight and at multiple sites. The visiting Tour de France was bigger, but with audiences spread across Yorkshire.

“It’s a good example of where local devolution can help with major events,” explains Brown. “Because we have a concession, a financial arrangement with Merseyrail as operator, it has enabled us to put in all the capacity available, all in six-car formations instead of the normal three.

“We can manage stations, close stations, put in the resources to get a proportion of those one million visitors away from here by train very quickly. That would be much harder elsewhere. We have that flexibility. It has worked better than ever before, but it still required Northern to get a special derogation from central government to move vehicles and so on.

“Liverpool City Council wants to do big events like this. One of the reasons they can do that here is a really good local rail system. We’ve put a lot of effort into customer service. People have moved away from the Cunard event by train with smiles on their faces, and they’ve paid a fare. That’s the ideal railway, isn’t it?”

“Rail North can understand the local economics better,” agrees Hynes. “We are encouraging Government to see rail spending as an investment, rather than as a cost. The Department has a business case to expand rail in the South because it is commercially viable. Up North it doesn’t - every time you expand the rail service, it costs you more money. So a cash-strapped central Government is never going to be particularly keen to drive growth, rather than merely accommodate it.

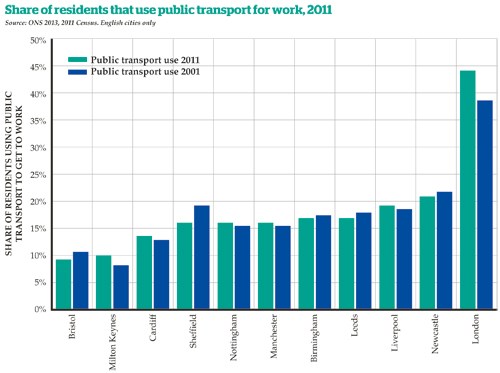

“The Northern cities take a different view. They want a better rail service in (say) Manchester, because Manchester is competing for inward investment with the likes of Dusseldorf. It is a very different mindset.The northern economy is changing. There is less work in factories and more work in city centres by people wearing suits. And that means we commute more.

“Clearly the DfT had to take the huge response to last year’s consultation on board. An approaching General Election also affected the franchise specification - George Osborne and Patrick McLoughlin wanted something positive and upbeat. Rail North wanted full devolution of both franchises. DfT said no, but went for a partnership agreement between them.

“I think in five years’ time the Northern product will have been transformed, because the specification for the next franchise is transformational. And that is partly because it has been influenced by Rail North’s involvement in the process.”

Rail devolution in other regions

Could rail devolution work elsewhere in the UK?

“I think it could,” says Merseytravel’s Brown. “We have a big geography, a high level of subsidy, and an historic lack of investment, so we have taken on perhaps the biggest challenge. The evidence to support it is here. The trains in Liverpool used to be called Miseryrail - they were the worst in the country for performance. Now they are among the best.”

Meanwhile, Northern Rail’s Hynes comments: “A local focus does bring local benefits. My instinct tells me the more Rail North control, the more money they will want to spend on it. At the moment, in-franchise change is such bloody hard work. In the future it will be easier to get good stuff done.

“Look at what LOROL did in London. It got the franchise, then Transport for London said it wanted to lengthen trains and improve stations. LOROL has done a great job because London was prepared to pay more for what used to be Silverlink Metro than central government thought was justified. For the DfT, Silverlink Metro was not part of its agenda. But London saw in it an opportunity to reduce congestion on the Tube and a chance to make poor areas richer. And they spent shed-loads of money on it.”

Mike Brown, managing director of rail and Underground for Transport for London, explains: “Our model of devolution is not a one-off for London. The differential lies between middle-distance routes and what you might call urban or suburban rail. In our model there is a recognition that revenue generation and ridership is a macro-economic factor, and not one that is at the disposal of any one operator to influence. Yes, they can do a bit at the margins - off-peak and weekends - but generally speaking, in big conurbations people use railways because they don’t have any viable alternative.

“If you have a model where revenue risk is taken away from the operator, and instead you incentivise punctuality, performance and delivery for passengers, it creates a different dynamic. That’s what we have done on London Overground, and it is equally deliverable in the other great urban centres.

“Manchester is the most well-developed parallel - it is key that there is well-developed political leadership. That doesn’t necessarily mean a Mayor, as we have. But there must be a single coherent voice that represents the urban area overall, coalescing disparate views.”

The West Midlands

West Midlands Rail will follow Rail North’s lead. In March, the Secretary of State formally agreed the process that will lead to rail devolution.

“While there are many similarities, West Midlands Rail will have governance structures more suited to local conditions,” says Toby Rackliff, rail strategy manager for the West Midlands Integrated Transport Authority. We will be looking jointly to specify and manage local rail services in the West Midlands travel-to-work area, in partnership with the DfT.”

West Midlands Rail is a group of seven metropolitan authorities and seven shire and unitary local transport authorities. Above it will sit Midlands Connect, similar in scope to Transport for the North.

WMR’s target is to create a more efficient railway that offers better value for the taxpayer, drives growth and reduces subsidy. Its proposition states: “Having a targeted, locally accountable contract with proper incentives on the operator will enable WMR to specify and manage rail services more effectively than the current national arrangements.”

The organisation aims for a single identity for the local rail network, a consistent fare structure across routes and operators, a common smartcard, and a standard approach to information. It would operate 112 stations and run more than 650 services a day, carrying 30 million passengers a year.

“The new London Midland franchise will commence in June 2017,” explains Rackliff. “It is likely to run until 2024, but will in any case need to expire before the opening of HS2 in 2026, as this will require a re-mapping of services on the West Coast Main Line.

“The DfT wishes to keep the current London Midland franchise geographic area, which will (for example) enable through London-Birmingham semi-fast services via Northampton to be retained. However, it is proposed that there will be a separate WMR business unit with its own distinct identity within the new franchise, and this will be the focus of the devolution proposition.”

It is proposed that the initial contract follows DfT standard arrangements, with the operator taking revenue risk. But during the franchise WMR would progressively take on greater management responsibility, and be in a position to take the revenue risk itself in subsequent contracts.

“There is a non-devolution model which still gets results,” points out CBT’s Joseph. “Groupings of local authorities such as the East Midlands Rail Forum can help to bring forward modest upgrades, such as easing of speed restrictions to make small journey time improvements.

“You don’t need devolved control to make progress, but you

do need strong local authority partnerships. That said, Jonathan Denby at Abellio Greater Anglia and its predecessors has almost single-handedly co-ordinated a rail strategy for his region, and brought every local authority onto his side. A first result is the ‘Norwich in 90’ policy.

“There are opportunities for regions which don’t want to go the whole hog. In the South West, they don’t really want to split away from the rest of the country. That’s because they do rather well out of the cross-subsidy that flows from a single operation running long-distance inter-city and local branch lines. They think separating them in a Rail North style would be counter-productive.

“But the principle of local control is without doubt. When snow is disrupting Merseyrail, the people in Merseytravel can see it is snowing, as they have to get home on the trains, too. So they can work with the train operators to ease the impact and manage the paperwork afterwards. The Department for Transport only sees the drop in performance data without understanding what caused it.”

Regional economic growth

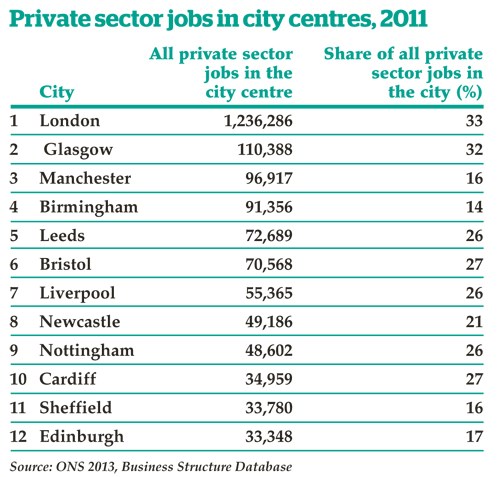

London and the South East drive the UK’s economy. Recent figures show that the UK economy grew by 0.8% in the first quarter of 2015… but the economy is not growing evenly.

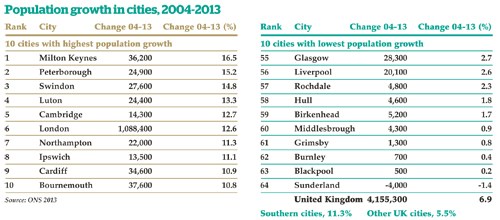

The Centre for Cities has produced a report (Fast Track to Growth, 2014) arguing that the economic divide between north and south is growing. The paper found that growth had been mainly driven by cities in southern England - for every 12 net new jobs created between 2004 and 2013 in cities in the south of England, only one was created in cities throughout the rest of Great Britain.

The independent research organisation said the number of jobs created in London rose by more than 17% between 2004 and 2013. But in Blackpool, Rochdale and Gloucester, there were falls of 10%.

Centre for Cities called on all parties to oversee “significant devolution of both fiscal and structural power, providing incentives for cities to support economic growth, and giving greater flexibility to ensure money can be spent where it is most needed”.

This appears to match the emerging agenda of the new Government. In his final Budget of the previous Parliament, Chancellor George Osborne made a series of policy announcements relating to what is now termed the ‘Northern Powerhouse’.

“Working with Transport for the North, the Government will look at rolling out better roads, quicker journeys, and improved rail connections between the major cities of the North,” he said.

Centre for Cities researcher Dr Ilona Serwicka says: “The focus on city-region transport is important. Almost half of commuters in cities live and work in different local authorities, and this number is likely to increase. The census shows that in the past decade, the distance that commuters travel to work has increased. But many city-region transport networks remain fragmented.

“Successful cities need continued investment in transport to continue to be attractive places for businesses and people. They also need more control over how their transport systems operate, in order to deliver the more integrated and co-ordinated transport networks that people and firms depend on.”

London Overground

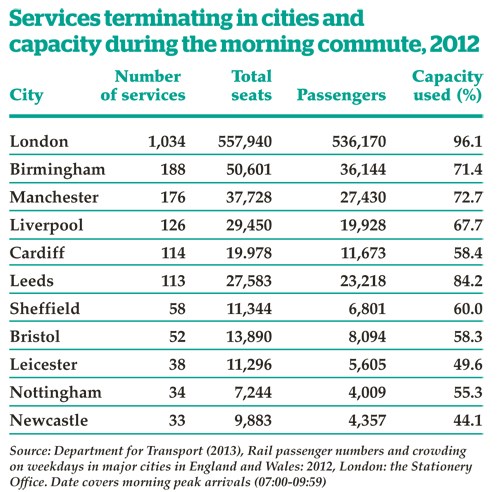

London Overground has been in existence for less than a decade, but already it has reshaped the capital’s rail map. And since May 31 it has grown even larger, with Abellio Greater Anglia’s inner suburban services transferring to Transport for London’s jurisdiction.

The routes are from Liverpool Street to Chingford, Enfield Town and Cheshunt via Seven Sisters, plus the separate Romford to Upminster line. These will now be operated by LOROL, the joint venture between Hong Kong’s MTR and Deutsche Bahn. MTR solo has taken on Liverpool Street to Shenfield as the first stage of its Crossrail concession.

Unlike most other train operating companies, London Overground is franchised by TfL and not by the Department for Transport. Prior to the latest absorption it already operated six lines and 83 stations. It carried 136 million passengers in the year to March 2014, and the inner West Anglia services will add another 20 million.

TfL says that as a result of regional control, new trains will be on the way. But the biggest change that passengers notice is lower fares. TfL says 80% of journeys cost less than before, and that no passenger will have to pay more because of the changes.

TfL says that as a result of regional control, new trains will be on the way. But the biggest change that passengers notice is lower fares. TfL says 80% of journeys cost less than before, and that no passenger will have to pay more because of the changes.

TfL sets fare levels, procures rolling stock, and determines service levels. The revenue split between TfL and LOROL is 90:10, and the franchise is due for renewal from November 2016.

“Our franchising model - a management concession - gives a better deal for passengers,” says TfL’s Mike Brown. “It focuses on a reliable railway, rather being there to generate income growth for the train operating company.”

Brown confidently predicts rapid growth under TfL’s stewardship. He points to a 268% increase in passengers on the North London Line since 2007, fuelled partly by the increasing size of London’s population.

He adds that work has started with a deep clean of all the additional stations, with redecoration, cameras and better customer information. “It’s not like we’re taking something that is in perfect working order,” he says.

TfL wishes to extend its direct influence further. It would like to acquire Southeastern’s metro services from Victoria, Cannon Street and Charing Cross, although Kent County Council has objected. So would those areas on the periphery of big devolved metropolitan railways lose out?

“I argued the case strongly when I made the bid to run the inner suburban parts of Southeastern last year,” says Brown.

“We ran into a lot of political opposition. Not party political, but geographical political from those outside the London boundaries who felt that their mid-distance services could somehow be diminished by a focus within London. My argument is that if you incentivise performance and reliability, then even at the margins you must get a benefit. Even for those routes outside the political governance area.

“We continue to make the case based on the evidence of what we are delivering. Our delivery record is the thing that will swing this. There will be a public cry for it. It is an inevitability. It is a matter of time. Southeastern - we want the routes out of London Bridge. Southern - the inner routes from London Bridge and Victoria. And South Western routes into Waterloo. You could almost draw a clockface around London. But the three big ones in the south are the ones I have my immediate eye on, because they are the ones where we can make the biggest difference - providing the south of London with the same level of metro service as those who live north of the river, and who get on the underground and the bits of overground that we already run.”

Mike Brown says he lost the argument with the DfT last year because Government did not want another operator in the mix at London Bridge during the Thameslink construction upheaval.

“We might have had some chance of preventing all the pitfalls that have been delivered there,” he counters. “It’s not about having one operator per station - it’s about having a clear remit to provide a consistent decent service.”

So is the DfT incapable of doing that?

“They have not been minded to work that way. They haven’t yet been persuaded that the interests of those on the periphery would not be disadvantaged by being answerable to local government instead.

“The Department could have done as we have on London Overground, but the impetus was not there. Yes, we had to spend money on the North London Line, but it was all within our budget settlement from Government. We just prioritised it differently.

“This was a terrible line. Its core section was running three trains per hour. It is eight now, and we’re going up to ten trains per hour in the next couple of years. Growth is phenomenal - capturing demand that was either on the Tube before, or using some main line stations, but it’s also new business, people discovering railways for the first time. By any stretch this is a major success story.”

The South East

“The South East has suffered from significant under-investment in its rail and road infrastructure.”

That’s the claim of councils in southeast England outside London. Really? The region of HS1, Thameslink, Crossrail and a large slice of Network Rail’s electrification programme, plus the youngest train fleet in Britain, is hard done by?

Apparently so. The region is lobbying for a larger slice of the financial cake, led by South East Strategic Leaders, a partnership of upper-tier authorities, and by South East England Councils, which covers all levels of council in an area encompassing Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, East and West Sussex, Hampshire, the Isle of Wight, Kent, Oxfordshire and Surrey.

The leaders are David Burbage (from Windsor and Maidenhead Council) and Gordon Keymer (from Tandridge District Council), who wish their comments here to be jointly attributed.

They point out that the busy commuter routes from their region to the capital rely on track layouts largely unaltered since the days of steam. They say the South West Trains routes are the only ones that fully pay their way and make a genuine financial contribution to government, yet the region has missed out on the levels of government investment seen elsewhere.

“Under-investment is stemming our economic growth potential,” they tell RailReview. “With £80bn profit for the Treasury over the ten years from 2002-12, the South East is the UK’s most profitable economy, greater than all eight core cities combined and more than Wales and Scotland together. Ongoing under-investment will hit the South East’s ability to return profits to the Treasury to spend on economic regeneration UK-wide.

“South East transport investment is vital, but this will only happen with greater devolution of funding and powers alongside greater investment in strategic transport projects that cannot be delivered without Government’s help.”

How would this be achieved? The council groups suggest that devolution of property taxes would have created a regional pot worth almost £10bn in 2013-14 - a combination of council tax, business rates and stamp duty.

It would represent devolution of 11% of total taxes paid in the South East, which could be used to fund investment in road, rail and digital connectivity.

“The economic success of the UK should be underpinned by every part of the country maximising its economic growth potential,” they say. “That includes all cities, whether major conurbations like Manchester or smaller yet equally important and innovative cities such as Milton Keynes.

“Greater fiscal devolution will enable us to make a greater contribution to investment in vital local infrastructure, to unlock economic growth. But it will not be sufficient on its own. The South East transport network is not just for local journeys, it is an essential link to international ports and airports used by travellers, freight and businesses across the UK.

“Despite this, the South East’s only public transport link between the major airports of Heathrow and Gatwick is by coach. The HS1/Channel Tunnel routes, access to key London airports and ease of freight transport from the South Coast are critical to the national economy, and why we need fair funding from the Treasury for larger-scale, nationally significant rail and road schemes.

“South East councils need greater power and influence over the franchising arrangements for relevant major routes and the operation of rail services. At present, democratically elected councillors are mere consultees in these decisions.

“Our relationship with London is far from the whole transport picture,” the councillors conclude. “One area where South East authorities would like to work together is on improving orbital rail routes to improve intra-South East commuting - routes such as the North Downs lines and connections from Dover to Southampton.

“Another area where there is significant interest in influencing rail covers the routes for passengers and freight into Southampton and Portsmouth.”

London is not a template

The model for devolved transport powers in London is not seen as a template for the rest of the country, although TfL begs to differ, believing its method is viable elsewhere.

Devolution is meant to reduce London’s grip and place decision-making in the hands of those who know best. But if new bodies are to control chunks of the country’s infrastructure, might this not over-complicate an already burdensome bureaucracy?

“Nowhere else in the world can you walk into a central government department and bid for contracts covering an entire rail network,” says Northern Rail’s Alex Hynes.

“Nobody does it like this apart from us. In Germany you have a number of states. You don’t bid for rail contracts in Berlin - you bid to one of the states. And they have inter-city and international rail services that seem to work fine, although the specification, letting and running of the regional contracts is devolved. So I’m sure it can work.”

With fragmentation, is there not a risk that parochial local needs override a strategic national view?

“The reverse is true,” says TfL’s Mike Brown. “There is a fundamental difference between the connections between the great urban centres and the connections within them. Those distinctions are not always clear. But I happen to believe in local accountability for local transport planning decisions.”

“The local authorities that want deregulation see it as one part of a much wider strategy,” concludes CBT’s Stephen Joseph. “They don’t take the orders for new trains in isolation - it’s about larger labour markets, it’s about attracting inward investment, it’s about what kind of city region we want to see.

“Development plans can be shaped around it. The Department for Transport by its nature has a franchise management focus that is much narrower. It doesn’t need to look at better bus connections and integrated smart-ticketing all over a city.”

“The devolution agenda is not about trains and buses,” agrees Rail North’s David Brown. “It’s about the whole economy. The current government recognises that transport has a fundamental role to play in improving economic growth, and increasing productivity. London has proved that with TfL. We have a financial stake in making good things happen.” n

Peer review: Christian Wolmar

Peer review: Christian Wolmar

Transport writer and broadcaster

|

Devolution is a vague concept and Paul Clifton does well to try to identify its precise meaning. As the article suggests, devolution is now seen as a ‘Good Thing’ by many politicians across the spectrum, with more and more expressing support for the concept. |

However, there is less certainty about what it means and its implications. The vagueness of the concept is leading to confusion, and may well spell trouble for railway companies who will have to deal with the muddle, and who may not have clarity about who is setting the parameters for their operations

The problem for the Devolvers is that each region is different, with issues over boundaries between lower and higher local authorities (such as counties and district councils). Moreover, some regions struggle to establish an identity, and even where there appears to be a strong local identity, devolution is not always popular.

The Labour government tried to create a regional structure by focusing on the North, where John Prescott organised a series of referendums in 2004 thinking these regions offered the best hope of success. In the event, they voted overwhelmingly ‘no’, and the process was abandoned before the more tricky regions such as the South East and the East Midlands were asked for their views.

Therefore the Devolvers have to tread carefully - and this is clear from Paul’s analysis. While he sounds positive about progress in the North, where the franchise requirements in the draft Invitation To Tender do suggest that a recognition of the region’s needs has been taken into account, it is far more difficult to imagine something similar happening in many other parts of the UK.

Merseyside’s success can be explained by the fact that it is a self-contained region, and the local authorities have joined together to ensure its success. London is comparatively simple, given it has Transport for London, which covers the whole area. But even here there are complexities - when Conservative mayor Boris Johnson tried to bring more services into the TfL fold two years ago, the plan was stopped abruptly by protests from his fellow politicians in Kent, who were worried that services to the coast would be cut back in favour of suburban trains.

It is not just the Kent Tory brigade. Over the years, I have received numerous protests from people living on the outer fringes of the Metropolitan Line, such as Chesham or Amersham. They argue that they get a poor deal from TfL, and that there is a democratic deficit because they cannot vote for the mayor as they live outside the capital. That has struck me as a tendentious argument, but it is a view that apparently has some resonance in Buckinghamshire.

Therefore, I am deeply sceptical about any attempt to devolve powers over the railways to local politicians in the South East. This region has no real identity apart from being part of the travel to work area of London. Politicians in the various Home Counties have little in common, and it is difficult to imagine them agreeing over the future of local train services. The same applies to both regions in the Midlands, and even in the South West there is a lot of difference between Cornwall and Devon.

That is why there are clear limits to devolution, which explains the very vague notion of exactly how it would work in various regions. While it is easy for politicians to argue in favour of it, actually devising ways to make it work is rather more difficult.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.