Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

"We choose to install ETCS Level 3. Not because it is easy but because it is hard.” OK, so neither President Kennedy nor Network Rail Chief Executive Mark Carne actually said those words, but the challenge for NR in installing advanced signalling compares in some way with Kennedy’s moon challenge.

Kennedy justified his ambition by saying that going to the moon would “serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills”.

Similarly, ETCS Level 3 signalling is Carne’s answer to the capacity challenge the railway is facing. He argues that it’s the only way to create the capacity needed for NR’s increasingly crowded tracks. And the breathtaking extent of that challenge can’t be understated - Carne is talking about rolling out across the country a signalling system that doesn’t currently exist. That will surely measure the skills and energies of railway engineers and planners.

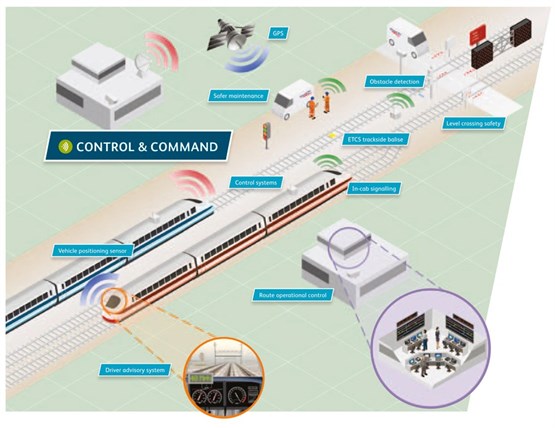

Level 3 has no lineside signals, a characteristic it shares with Level 2 (see panel). But it also has no train detection equipment fitted to the track, which is its defining difference. Removing train detection kit - whether track circuits or axle counters - cuts NR’s maintenance burden and boosts staff safety by reducing the number of staff it needs on or near the line. The improvement in capacity comes from Level 3 allowing moving block signalling, which should allow trains to run more closely together.

A more flexible railway

Lest this sound like a resignalling project, Carne counters that it’s just one element of his wider Digital Railway revolution (that also includes ticketing and timetabling) to create a more flexible railway that’s better suited to its customers, whether passenger or freight.

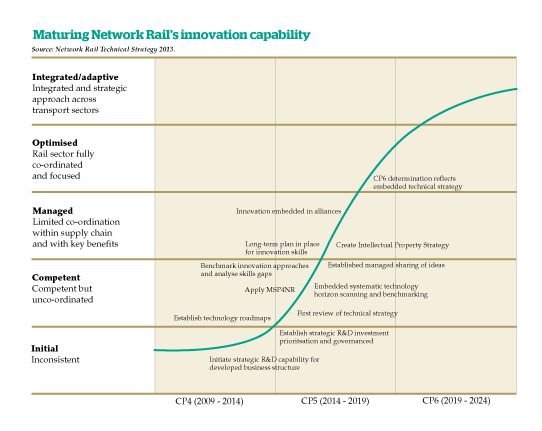

To add to the challenge, Carne wants all this done by 2029. To set that in context, compare its vaulting ambition with the Department for Transport’s 2007 plan that had Level 2 being installed by 2038, and 2012’s Rail Technical Strategy that suggested Level 3 installation should start in 2025 following a decade of development (see panel, page 12).

In contrast, NR is now talking about developing the idea of its Digital Railway in time to be included in the Initial Industry Plan for Control Period 6 (2019-2024). At the speed the railway’s planning wheels turn, that gives NR around two years.

To further increase the pressure, not so many years have passed since Britain’s railway last tried to introduce main line moving block signalling technology. Arguably, Railtrack’s demise was prompted in part by its 1999 admission that it couldn’t bring moving block signalling as planned to the West Coast Main Line, as part of a massive upgrade programme for Virgin’s 140mph tilting trains. The fatal accident on shattered track at Hatfield in 2000 played a bigger part, but both combined to depict Railtrack as a failing company.

In Railtrack’s place came Network Rail, with a mission to both restore the railway and the public’s confidence in it. Things have improved - passengers are now using trains in greater numbers than at almost any time in the last century and on a network vastly smaller than that the ‘Big Four’ inherited in the early 1920s. But NR has nonetheless been criticised for poor performance and delayed projects, even though passenger safety has greatly and consistently improved.

It’s the increasing numbers that have prompted Carne to unleash his Digital Railway revolution. Not every train has every seat occupied, but there is continuing pressure to run more trains at times passengers want them.

Nowhere is that more apparent than on the East and West Coast Main Lines, north from London. On both routes, open access operator Grand Central is pushing to be allowed to introduce new services or increase current provision, but it’s fighting against a view that the lines are already full with no space for more trains.

Meanwhile, on the Leeds-Manchester route, TransPennine Express is witnessing falling punctuality since the introduction of an extra hourly train path last May. The more crowded tracks become, the harder it is to run trains punctually.

Speaking to RailReview in November, Carne recounted a recent visit to the East Coast Main Line. He stood on a bridge over the line, and could hear birds singing for several minutes before any train passed. And yet, he said, he was told the line was full.

He likens his Digital Railway plan to the step change in air traffic control capability that came with computerisation. It increased capacity in a system that had been operating at its limits.

Carne has charged Jerry England with leading the revolution, and England is now assembling a team to take the ideas forward - both the European Train Control System signalling and the ticketing and information strand. The test bed for many of these ideas is pencilled in to be the Essex Thameside line - still better known as the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway, currently operated by National Express under the c2c brand.

Noting the precursor work from the Rail Technical Strategy (see panel), England tells RailReview: “Somewhat independently of that Mark has arrived, getting on for a year ago now, and as a newcomer and an outsider from a different industry he’s taken a look at the railway, and not surprisingly said that it looks pretty much like we haven’t really embraced new technology in the way other industries have.

“And while we have plans (or at least ideas) to implement that sort of technology, they are pretty long-term. And as you’ll be aware, just taking ETCS, the current plan takes us through to 2062 before we have ETCS everywhere.

“If you look at it in the cold light of day, it’s probably a questionable plan (to say the least) for having technology that takes that long to roll out. Because as sure as eggs is eggs, it’s going to be overtaken long before completion by something else. So I think the first question was probably around why that takes so long, and why can’t we do it quicker.

“The other major driver for this really is around capacity. The growth story of the railway is fantastic. It’s doubled over the past 20 years or so in terms of passenger journeys. We’re now at record levels of 1.5 or 1.6 billion passengers a year, which is about where it was back in the 1920s. We’re at or around the point where there are as many people travelling on the railway as there ever have been - but on a much smaller railway. There are significant pressures, particularly around the more urban parts of the railway - not just in and out of London, but in and out of the other big cities as well.

“While HS2 or possibly other high-speed links and other more strategic links are definitely needed to provide some of that more inter-urban capacity, there is also a need for a lot more capacity in and out of the cities in a more commuter type of arrangement than any high-speed link is going to give us. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to realise that building new railway lines in and out of cities is a pretty tough thing to do.”

Just how much extra capacity can be realised from ETCS varies, depending on the route. England reveals that initial work has shown that a 30%-40% increase might be possible on the South West routes from London Waterloo.

“We’ve had a look at a couple of other routes, and while I would say the 30%-40% is probably at the high end, it certainly feels doable that we could get into a lot of routes a 20%-30% increase in capacity, by smarter operation of the trains through a more digital approach to the signalling and control system.”

For the West Coast Main Line, the increase could be much lower. Its mixed traffic nature leads England to say that it might just be “single-digit percentage improvements in capacity”. And he stresses the need to continue with High Speed 2, as NR’s Digital Railway plan does not make HS2 redundant.

Changes in ticketing

The past few years have also seen major changes in ticketing. No longer must every passenger have a small piece of card. Some tickets already exist only on mobile phones; others are printed at home onto ordinary paper; yet more exist on smartcards, marketed under an array of different names even though they are essentially the same thing.

Says England: “In this day and age, other railways and certainly other modes of transport have gone into much more digital ticketing using smartphones and other devices. There’s no reason why we can’t do that, potentially getting rid of ticket barriers, and having much more intelligent detection systems that allow operators to know who’s there and who isn’t there and what tickets they have and don’t have. So we want to try and bring some of that in.”

There will be many who question why Network Rail needs to be involved in ticketing and England admits that it will be a project not just for Network Rail, but one for the whole industry to take forward.

Accurate and timely information is the other Holy Grail. England tells RailReview: “It’s not just to improve the information available to passengers on the railway about the railway, but to provide much more end-to-end journey information so that people can have on their smartphones or other devices a much more end-to-end journey plan. One that will take them from wherever they started (be it their home or their office, or anywhere else) to wherever they are going, and provide them with the right level of information - be it about cars and car parks, buses or trains, airports or whatever. And that’s all added together and in one place. The technology pretty much exists, so why not make it more fully available?

“Then, if there is disruption, it would allow everybody to provide a much better service in terms of providing alternative options for people, advising them of changes they may need to think about, or alternative routes, or providing taxi details or whatever.”

Certainly, there have been recent information improvements, but these have not come from the railway, but from third parties. For example, the realtimetrains.co.uk website, developed by Tom Cairns when he was an undergraduate, has vastly improved access to train running information.

And in London, the Citymapper app for mobile devices can display routes to and from any location in the capital by bus, Tube, taxi, cycle or foot. It calculates journey times based on how long it takes to walk to the nearest bus stop or Tube station, how often the buses or Tubes run, and how long it might take to walk at the other end. Both show what can be done with information.

England reckons: “One of the things I’m quite keen to do in my new team is to engage, perhaps only on a temporary basis, with some of those people, to understand what is the art of the possible and then think about how we might realise that. Is that something we either want to realise or that we can realise? And if so, how? If it’s just as simple as ‘here’s a bunch of information or data, just work with it and sort it out’, why wouldn’t we do that?”

Network Rail need not develop its own app and arguably the train operators need not (although they might choose to in order to help their customers), but if the provision of good quality information results from NR’s switch to ETCS, then all the railway’s customers will benefit.

England admits that even with all this extra information, NR and train operators would likely still struggle to say how long disruption might last, or how long a problem might take to fix. Of course, with less equipment on the trackside to go wrong (albeit with more on the train), it should be that faults that delay trains become fewer. For context, the Office of Rail Regulation’s latest report into NR notes that delay minutes caused by track circuit failures have increased by 23.1% over the last year. Operations delays from signalling have risen by 27.8%, it says.

Cutting delays from these causes will form a major part of the business case behind the Digital Railway. England admits that an initial review showed a case positive enough to justify further work, although he is not willing to reveal further details.

The more thorough case will conform with HM Treasury’s Green Book rules, now that NR is funded directly by government rather than through private money backed by government guarantees. The business case will need to balance the costs of ETCS development, design and installation (as well as the costs of replacing existing signalling before it’s life-expired) with the benefits of improved reliability, capacity and lower maintenance and running costs.

England explains: “Certainly, there’s a big part of the business case which is accelerating the renewal and replacement of existing signalling equipment that won’t be life-expired. We did a very high level piece of work in the summer which does show that there is a business case - and it looks like quite a good business case for doing that - if you offset the sunk costs of the infrastructure with the increase in capacity, availability and reliability on the network.

“There’s a lot more work to be done on that over the next 12 months or so, to get those numbers to something that I would be comfortable publishing. We need to be realistic about it as well.

“While there is going to be (on a net present value basis) a very good business case for doing this from an affordability point of view, it is likely to mean that if we want to do it at the scale and pace we’re planning to, there may well be a peak of expenditure in CPs 6 and 7 that effectively, against the current plan, will bring forward expenditure that was going to be in CPs 8, 9 and 10.

“So, overall we could be spending less money, but there is a question around the affordability of doing that. We’re going to have to work that into the equation as well.”

This spending also comes at a time when government is likely to be heavily committed to building HS2, which goes some way to explaining why Mark Carne has already been to No. 10 Downing Street and why NR people have been to the DfT. England tells RailReview that reaction has been generally supportive, but it’s clear that for best effect, the railway industry will need to be united in pushing the Digital Railway and that both the industry and the supply chain must be able to deliver their promises.

“We’ve been into the top of the industry, we’ve been to the Rail Delivery Group and more recently the Rail Supply Group, RIA and other supply chain forums. We’ve spent quite a lot time over the past few months with those stakeholders, helping them understand what we’re trying to do here and what we’re suggesting we do, trying to get their high-level buy-in, which everybody has given,” says England.

Now he needs to build his team. He’s appointed a development director, and expects to soon add a transformation director in place of the current temporary, on-loan, arrangement.

One early decision will need to be on the future of the current ETCS programme (see panel). It is best described as a mosaic of installation driven as much by signalling renewal dates as by anything else. It sees, for example, the Aberdeen to Nairn route converted to ETCS in 2024, and the Blyth and Tyne freight lines in 2021.

A fatal accident at Santiago de Compostela in Spain in 2013 showed the risks in switching from one signalling system to another, particularly if one incorporates speed supervision (as ETCS does) with another which does not. It’s a risk Mark Carne specifically mentioned when quizzed by RailReview.

England recognises the need for a decision about the current plan: “We haven’t stopped it at the moment, but one of the first jobs we have over the next weeks (we’ve not got much longer) is to revisit that plan. We’re not stopping doing the Great Western and we’re not stopping doing the East Coast.

“What I do want to understand is how we migrate those from Level 2 to Level 3. Then what I want to understand is what happens beyond that, to make sure that we have our current ETCS rollout plan fitting onto our overall Digital Railway plan. That’s a piece of work that we’re going through - it’s a high-level piece of work to look at what we would do and where in CP6, and then what we would do and where in CP7, but that’s about the height and the level of it at the moment.

“Obviously, what we want to do is more by line of route rather than (as now) based on signals renewals, which is a bit of a patchwork quilt at the moment. So one of the plans will be how we get whole routes onto ETCS, so that we can run an ETCS service from one end to the other instead of having to switch several times in the middle. I think that in the short-term we might be looking at life-extending a few things, so that we don’t have to rush in and replace them immediately with something that we haven’t quite worked out what it should be yet.”

As a top-level ambition, aiming for ETCS Level 3 is admirable. However, it’s not even available today off the shelf. Flick through the brochures of signalling companies, and Level 3 barely rates a mention save for a regional version running on remote lines in Sweden.

UNISIG, the European rail industry body charged with developing the specification of Level 3, has still to complete its work on behalf of the system authority, the European Railway Agency. This leaves NR to either develop its own specifications or to wait for UNISIG. The former has the risk that Britain ends up with a bespoke system based on ETCS but not of ETCS, with all the attendant costs of non-standard equipment. The latter will mean its chances of achieving Carne’s deadline look even more challenging.

England is alive to this problem: “There are two things to do. Firstly - and we’ve already started to get this set up - we need to form a good relationship with the likes of the European Railways Association and the European organisations, to get their help and support in what we want to do and to make sure as far as we can that if, as I anticipate, we are the developers of ETCS Level 3, then we are developing it in a way that as far as we can will fit the rest of Europe and the European model. Again, there has to be a balance there - between how much we can get the balance between the speed and the design right.

“The other thing is how we involve the supply chain. What I would like to do is to effectively form some sort of consortium of not every single supplier, but a small number of suppliers that we can work with collectively to develop this technology. We develop it as open technology, so that once we develop it we can then go through the normal competitive processes for the more detailed design and installation work.”

Many of the technical challenges surrounding Level 3 have been worked through in various systems that act in a similar way. According to one experienced signalling company, the challenge lies much more in standardising these ideas and putting them into one specification.

Resignalling

Doubtless engineers will bring a way of ensuring the integrity of a train. Detection equipment on the track in Level 2 identifies a split train, but Level 3 relies on the train knowing that it’s complete. For multiple units with wired connections between every vehicle, this could be simple. But it’s a bit trickier for a train of freight wagons connected by air brake hoses.

The difference between Level 2 and Level 3 must be taken into account when planning resignalling. Should a Level 2 scheme come with changes to track layouts, then the new detection equipment installed will become redundant early when Level 3 takes over. Better to change layouts only when shifting to Level 3. Effectively, this means that NR should resignal straight to Level 3, leaving only the East Coast and Great Western lines on the interim Level 2 system.

One advantage to Level 3 is that it does not rely on current infrastructure. A driver could drive a suitable fitted train on a classic line, obeying signals as normal, while ETCS kit runs in the background (clearly without control of traction and brake systems). This means that if NR is to use the Essex Thameside LTS route as a trial, those tests can continue in parallel with normal operation.

England is ambitious: “If we’re to achieve my goal of having the first proper implementation of ETCS at Level 3 in CP6, then having a demonstrator of some description down on Essex Thameside by the end of CP5 sounds like it ought to be possible.”

He adds: “My goal, a bit like Mark’s challenge to me, and I’m not sure how easy it’s going to be, but my goal is that the next project we do with ETCS will be a Level 3 project. I want to get to the point where the first project in CP6 is a Level 3 project, which may be quite a tall order to get ETCS from where it is today (which is not very far) to fully implementable in four years. That’s quite a challenge.”

Involving National Express as the operator of Essex Thameside is obvious, but NR will need co--operation and involvement from all railway companies. England is keen to push the boundaries, but is wary that uncontrolled development could take the project down blind alleys.

“I do want to be somewhat cautious about some of the enthusiasm that we’ll all have about getting some of this stuff out into a lot of places quickly. Because unless we’re sure this technology is really robust and works, it’s not only likely to cause us a lot of problems, it will cost us some money collectively. And it isn’t going to do the cause of the Digital Railway any good if the first thing that people see is something that doesn’t work.”

A further risk lurks in the Digital Railway itself - if it distracts NR’s senior management from the daily job of running the railway (see panel). Having a visionary chief executive is great, but not if he doesn’t have a top-notch chief operating officer fully astride the day job right now.

NR has an incredible amount to do in Control Period 5, which started last April. There are major enhancement programmes such as Great Western and trans-Pennine electrification (with North West electrification having already run into difficulties), major work for Thameslink and Crossrail, Edinburgh-Glasgow improvements (including electrification) and the Northern Hub.

There is also a host of renewals. NR is 52% behind its points renewals plan and its signalling programme is significantly behind schedule, according to ORR. It predicts that NR will not recover the shortfall by the end of 2014/15.

Carne knows this. He wrote in his November quarterly report: “We recognise that we must deliver what we have said we will deliver and our focus is on transforming current performance to deliver the railway our customers require. It is only if we do this that we can focus our attention on the future of the railway, one which will be increasingly digital. This will involve the whole industry and if we are to succeed, how we work with all our stakeholders will be crucial.”

Staff to play key role

He has lost key staff to HS2, and his operations managing director resigned last September. Staff will play a key part in delivering ETCS, and it’s for this reason that England describes the Digital Railway as a change programme enabled by technology, rather than as a technology programme.

“This isn’t about ‘we’ve suddenly had a great new idea for the railway and we’re going to go off and do something completely different’. It is pretty much ‘we have a technical strategy for the railway and we’re putting some real momentum and pace behind it, and instead of letting it take 30, 40 or 50 years before we implement it, let’s get on and do some significant parts of it over the next 10 or 15 years’. That for me is message number one - that this is not something brand new, it is actually implementing faster and quicker and hopefully smarter than what we have already actually agreed on.”

This means taking a huge number of railway staff, at all levels, with him and with Network Rail. It also depends on the ability of the supply chain to cope with a hefty increase in work, in an area of new technology where it has little practical experience.

Says England: “We’ve talked a lot about developing the technology and how we do that. We can still get to the point where we’ve developed the technology, but if we don’t have the capability and capacity within the supply chain in the industry to deliver it, then we’re still not going to be any further ahead.

“From a supply chain point of view, that all ought to be do-able. In a simplistic sense, there ought to be enough suppliers out there, but we still have to go through that process. We still have to convince ourselves that that is the case.

Technology skills

“I think the bigger changes and the bigger challenges are around the people within the industry, and the people who are going to have to manage and operate this technology when it comes in.

“We’ve said with ETCS that we think it’s going to touch around 55,000 people. My guess is that with the Digital Railway, it’s probably getting on for double that - it’s going to be nearer 100,000 people. It will pretty much touch everybody that’s involved with this industry at the moment.

“There will also be a natural turnover, so we’re already bringing in people with those technology skills. But there’s still going to be an awful lot of people who we’re going to have to retrain and reskill to deal with stuff in a different way.”

In case you’re wondering (!), there’s no price yet attached to the Digital Railway, but it’s likely to be large, as are the potential savings. It will ask a great deal of the supply chain, railway staff and Network Rail’s management. It’s the biggest, high risk-high return costly project Network Rail has ever attempted.

Peer review: Alf Roberts

Peer review: Alf Roberts

Former chief executive of the Institution of Engineering & Technology

The principal subject of this article is the European Train Control System (ETCS), a concept specified in outline as long ago as 1996, but on which no progress has been made. The radical proposal is to therefore advance the timescale for significant progress from 2038 to 2029! This to be part of a much broader vision of the ‘Digital Railway’.

There are two potential problems. The article recognises that a key managerial challenge is the optimisation of business processes and the role new technology can play in this, rather than introducing technology because it’s there or (worse still) because it’s hard.

The more specific and well-defined the project is before you start, the greater the chance of success. It seems to me that at this stage ETCS can be sufficiently well defined while the ‘Digital Railway’ cannot, so I would be concerned about making the former contingent on the latter.

Even ETCS will require consensus between the train operators and Network Rail on a wide range of operational and technical issues, with decisions having to be made on the basis of persuasion rather than executive edict. On past experience, this will inevitably put the time line at risk.

Which brings me to the second problem - potential incompatibility between the rate of technological develop-ment and the timescale for implementation.

Future-proofing will need to be a key element in the risk management strategy for the project. Of course, there is the advantage that the proposed technology is now central to many other sectors who will have (along with suppliers) a vested interest in the future-proofing issue. Nevertheless, few sectors other than energy tend to think, let alone plan, on 15/20-year time horizons.

Concentrating now specifically on the concept of ETCS. In principle, it must be a ‘no brainer’ to move from the manual ‘stop-go’ approach of controlling the network (using outdated electro/mechanical equipment) to one based on digital technology that will allow the optimisation of the operation of the network against a much wider range of parameters than just safety, although that will clearly remain paramount.

As the article says, this is not a resignalling project, but a radical revision of how the second-by-second running of the railway is managed. However, based on the article, the business case still seems to be a work in progress. The project will stretch all NR’s resources, and probably displace or defer other projects.

Given NR history and current challenges I am sure, therefore, that the NR Board will wish to see:

- A robust financial appraisal route-by-route as well as on a network basis, to confirm that the additional capacity will emerge and to establish the optimum rollout programme.

- An evaluation of the implications for the day-to-day operation of the railway.

- A convincing risk management plan particularly related to elements that either lie outside NR’s direct control (TOCs, HMG, for example) or are potential sources of internal priority clashes.

The article leaves me thinking that NR is a long way away from this at the moment - perhaps another reason for tight control of mission creep at this stage.

Not only does the article raise concerns about NR having enough skilled staff to implement the project, it also questions the capability of the traditional signal suppliers to meet NR’s timeline. The technology to be used is neither new nor particularly high-tech, but it is ubiquitous. Given this, apart from the future-proofing, the technical risk associated with the project seems to me to be low.

And even the future-proofing is controllable, provided excessive bespoking is avoided. Software updates are relatively straightforward, as are hardware ones provided you are using general purpose equipment. It seems to me, therefore, that two birds can be killed with one stone here, if NR looks beyond its traditional suppliers to implement this project. The involvement of the TOCs in the project is barely acknowledged - and yet it could be crucial. Replacing the traditional role of the driver as the sole ‘controller’ with a partnership between man and machine may give rise to a plethora of technical and staff relations issues.

Some TOCs have already experimented with the use of on-board computer-based driver “advisory” systems, to help drivers to minimise fuel consumption while maintaining the timetable. The lack of a co-ordinated approach to this (despite a national working group) may point to problems ahead for ETCS, as may the fact that issues with the trade union have led to the system being ‘advisory’, despite the very significant savings these systems have been demonstrated to offer.

Peer review: Chris Jackson

Peer review: Chris Jackson

Partner at Burges Salmon

Mark Carne is right to be visionary and challenging in his approach on the Digital Railway. Philip Haigh adopts and adapts JFK, but other quotations reinforce the issue too.

“One of the greatest pains to human nature is the pain of a new idea.” (Walter Bagehot - 1869).

“Optimistic forecasts of equipment availability are a characteristic of the railway industry… having reviewed the evidence as to the current development of ETCS, the availability of resources and other commitments that the industry faces, we conclude that regulations should provide that all trains running at over 100mph should be protected by ETCS by 2010.” (Uff/Cullen Joint Public Inquiry into Train Protection Systems - 2001).

Continuing to run an analogue railway in a digital world is not feasible. Much current rail technology remains derived from its Victorian roots. Fixed block signalling principles are still embedded in the foundations, overlaid with emerging technologies of the later 20th century such as BR-ATP, TPWS and GSM-R. Passenger interfaces are a mixture, with the orange ‘mag-stripe’ ticket sitting alongside Oyster, contactless payment and smartphone apps.

If the need is clear, its achievement will be daunting. It will require all the drive and organisational skills that the collective leadership of the industry possesses.

It has proved difficult for M&S to introduce a new customer website and for Tesco to keep up with market and technology shifts. Air transport has digitised airspace and on-board services, but for the moment at least still doesn’t provide routine on-board calls and emails (thank goodness!). How much more daunting therefore is the achievement of an economically transformative - but at all times safe - technical revolution across the complexities of the rail system?

It is a conceit to say that rail is different to other modes of transport or to other complex areas of business or industry. It is, however, an inescapable reality that it is a dynamic system with particularly complex interfaces on every level.

Network Rail is a key/critical player, but only one part of the matrix. The Digital Railway will need two inter-dependent sides to its coin - the customer interface and the operational interface. Retail and business customers will require ever more accurate real-time data, but if the Digital Railway is seen primarily as a supply side/track and train movement challenge (however massive and necessary that aspect), then passenger and freight customers will see an increasing gap.

An integrated approach to technology and ‘big data’ will throw up operational, social, regulatory and legal issues.

Who owns the IP? Are the systems truly ‘interoperable’, or will suppliers seek to protect their R&D and their own bespoke solutions? Who will mandate the ‘right’ online solution(s) or applications in a babble of emerging competitive IT solutions? How will the Ticketing & Settlement Agreement and Franchise Agreements evolve to new demands and new tech? Who owns and can use the customer ‘big data’ set? Will we resist the siren call of UK or local ‘enhancements’ that add time and complexity? How do we mesh train data with customer needs? How do we manage the transformative change in a way that is safe at all times?

When technology is changing every two to three years, and 5G is starting to make current technology look old before it is even fitted, how do we manage investment horizons of 30-50 years and franchise terms of seven to ten years?

The Digital Railway is essential and Mark Carne is to be applauded for both his clear challenge and his vision. It is deliverable, but delivery will require formidable challenges - technological, operational, cultural and legal, to be mapped and tackled holistically.

Peer review: Cliff Perry

Peer review: Cliff Perry

Former chairman of IMechE

The global strength of railways lies in their sustainability and high capacity potential. Road solutions based on the internal combustion engine now seem very 20th century. Electrified railways running on clean electricity deliver sustainable transport on current technology.

The vision of the Digital Railway therefore deserves universal approval. Who would vote against perfection? We are desperate to move our Victorian railway into something fit for the next 100 years and vision at the top of Network Rail is a vital component of success. The direction of the vision also aligns positively with the current Railway Technical Strategy. Another plus.

Someone has to lead the efficient adoption of relevant system technologies. If NR translates the promotion of this vision into leading genuinely collaborative development, that also scores highly. So good marks for Vision, Leadership, Alignment and Co-operation - all nine out of ten.

Reasonable challenges which follow are: Is it the right vision? Is the technology available? Are the timescales achieveable? Will the industry buy it?

- Right Vision? Partly. ETCS will become the cheapest way to resignal a railway. However, heavy rail has to move at Metro frequencies to meet demand, so the busiest lines need Automatic Train Operation as well. This is more than ETCS level 3, as currently defined. At the other end of the UK railway spectrum, on some lines operated by one train any signals at all represent unnecessary costs.

There are many capacity killers on our network, such as short trains, flat junctions and differential train performance. A single signalling solution will rarely provide the best business case for improvement.

- Is the technology there? Not yet. The current technology gap in UK rail is between what is possible and what we actually do. This vision needs new technology. Currently we are fitting brand new IEPs with redundant signalling equipment because we cannot deliver level 2 on the Great Western Main Line. Crossrail trains will operate on three different systems with undesirable transitions on every trip.

The devil is also in the detail - safe assumptions about guaranteed braking rates will always give enough gap between high-speed trains to hear the birds sing - and may well lower the capacity of Fenchurch Street.

- Are the timescales achievable? Highly doubtful, ETCS is a European project and the thought that we can unilaterally accelerate its development is over ambitious. The long-term costs of ending up with a UK-specific version are not worth one Control Period’s delay in implementation. Let’s get it right, not get it quick.

- Will the industry buy it? Not yet. NR has to commit to deliver on time to allow others to invest in the vision.

History of ETCS delivery is the problem here. Fitting the trains destroyed the reliability of the Cambrian Coast fleet, and operators may well be suspicious of NR pushing its signalling and control costs onto them.

System-wide collaboration is essential if we are to avoid producer-led ticketing solutions that do not suit the customers (or their representatives on railway Earth, the train operating companies). Real-time service adjustment and timetabling is overdue, although the best railway for producers and customers alike is one where everything happens to plan A.

Finally the skills gap: new railways, new trains, accelerated spend and major projects all need high-quality engineers to manage the changes safely and cost efficiently. Do they exist and are we getting the best into the industry in sufficient quality to meet the challenge?

- Summary: Vision 9/10, Reality check 4/10.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.