Fifty years ago, 43 people lost their lives in the Moorgate Tube crash. Mike Lewis was at the station that morning, and vividly remembers the scenes on one of the Underground‘s blackest days.

Fifty years ago, 43 people lost their lives in the Moorgate Tube crash. Mike Lewis was at the station that morning, and vividly remembers the scenes on one of the Underground‘s blackest days.

It was 50 years ago - a Friday morning, February 28 1975.

A crowded London Underground train ploughed through a buffer stop and along a sand drag at Moorgate station, crashing into an end-tunnel wall at more than 30mph.

It was the Underground’s worst ever accident involving a passenger train, leaving 43 dead and 74 injured. And the subsequent rescue operation was one of the most difficult ever undertaken on a British railway.

The story has some personal significance for me. I was in the station, on the adjacent platform, at about the time it happened. I didn’t see the crash itself, but I did witness the immediate aftermath.

I had boarded my Northern Line train at Hampstead station for my daily commute into the City. The train arrived as usual on Platform 8 at Moorgate.

Everything seemed normal. But as I ascended the escalator, I noticed six firemen hurrying down the adjacent escalator. At the main entrance, station staff were turning away arriving passengers. Several fire engines were parked outside.

At first, none of this aroused my curiosity. That might sound surprising, but remember that this was at the height of the IRA’s London bombing campaign. Bomb scares and terrorist alerts were by no means unusual. Only a few nights before, I had been evacuated from my own flat because of a suspected device in a neighbouring building.

However, as more staff arrived at the office and reported “something big” going on at Moorgate station, I decided to investigate.

Stepping out into London Wall with two colleagues, the first thing we saw was a roped-off area in front of the building opposite. It turned out to be an emergency blood donation centre. Students from the nearby City of London Business School were queuing to give blood.

In Moorfields (a narrow street running along the west side of the station), half a dozen ambulances were parked. A dazed woman - her hair, face and bare legs black with soot - was being led to one of them. Apart from that, the street was surprisingly calm.

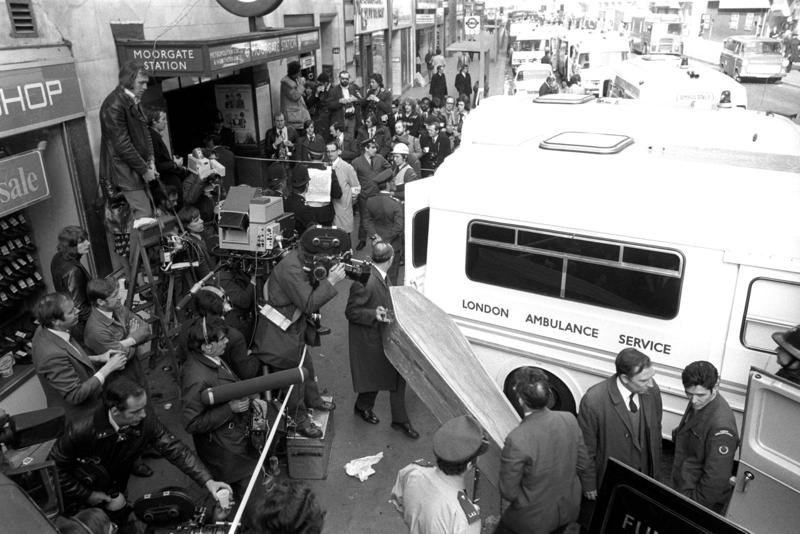

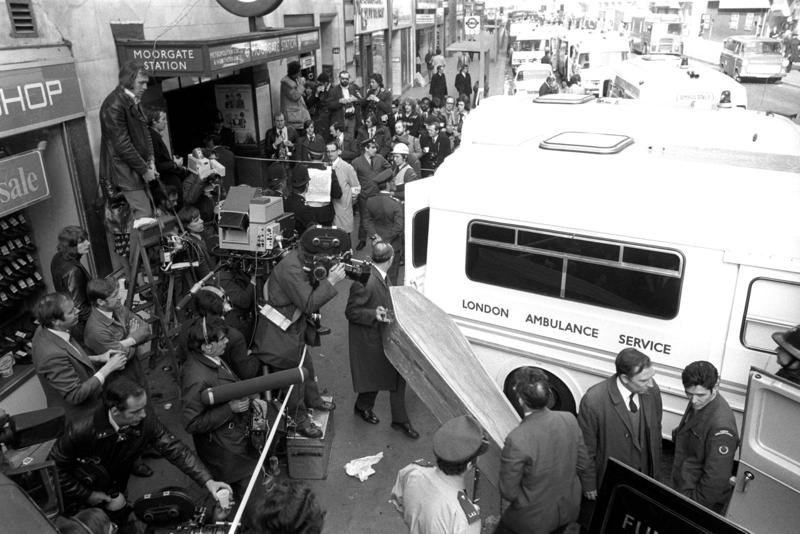

Moorgate itself was another story. Here, the area was humming with activity. The entire street had been cordoned off. Fire engines, police vehicles and ambulances were coming and going, and emergency personnel were hurrying around. A mobile command centre had been set up, and we saw at least one TV news crew at work.

Now, the last thing that emergency workers want in these circumstances is curious on-lookers, so we sensibly went back to work. It was not until I arrived home that evening and tuned into the news that I found out what had happened.

At that point, the death toll was put at 29, but was expected to rise considerably. An unknown number of survivors were still trapped in the wreckage.

The crash happened on Platform 9, a terminal platform on the Northern City branch. The train, comprising six cars of 1938 Tube stock, was the 0838 from Drayton Park. It was driven by an experienced motorman, 56-year-old Leslie Newson.

Witnesses on the platform said the train had entered the station much faster than usual and showed no sign of slowing down. The driver appeared to be sitting calmly at the controls, his right hand on the dead-man’s handle, looking straight ahead, with no alarm or panic on his face.

What happened next was truly horrific. As the train hit the tunnel wall, the front car was crushed down to one-third of its normal length. The front and back of the car jack-knifed into the tunnel roof, while the front of the second car buried itself below the back of the first. The third car then jumped up over the rear of the second, ending up squashed between the top of that car and the tunnel roof. The rear three cars were badly damaged but remained on the track.

By the time I and my colleagues walked past the station later that morning, a full-scale emergency was under way. Medical teams from two nearby hospitals - St Bartholomew’s and the London - had set up a triage station. The ambulances we saw were ferrying the most seriously injured to hospital.

For the rest of that day and over the weekend, the crash dominated the media.

The main story was the horrendous conditions faced by the rescue workers. Any subterranean rescue is fraught with difficulties, but this one was truly dreadful.

It was deep under ground in an extremely confined space with no access for heavy lifting equipment. Radio communication with the surface was poor.

Within moments of the crash, the platform had filled up with a dense black cloud of soot and grime, leaving the area in almost complete darkness. With no air circulating, the heat soon became intolerable. The temperature eventually exceeded 40°C.

Firemen working on the rescue stripped off their tunics and helmets, contrary to regulations. They had been ordered to work for 20 minutes at a time and then to take a break, but most of them carried on, despite the heat.

Local cafes and pubs, helped by teams of volunteers from the Salvation Army and the WRVS, delivered a constant supply of cold drinks to the rescuers.

A witness quoted by The Times described “the blackened faces of firemen sitting outside the station in the cold, drinking tea from local sandwich shops in complete silence”.

Another newspaper carried a picture of an exhausted doctor, grabbing a few moments rest on a station bench.

The rescuers had to work in an impossibly tight space. In the front car, there was less than four feet to stand in.

Doctors worked on their knees while firemen cut holes in the mangled wreckage. One doctor spoke of having to step on a dead body in order to reach one of the injured.

At one point, an engineering company set up an industrial fan at the top of the escalators in an attempt to provide some ventilation. But it only succeeded in blowing the dust around and so was abandoned.

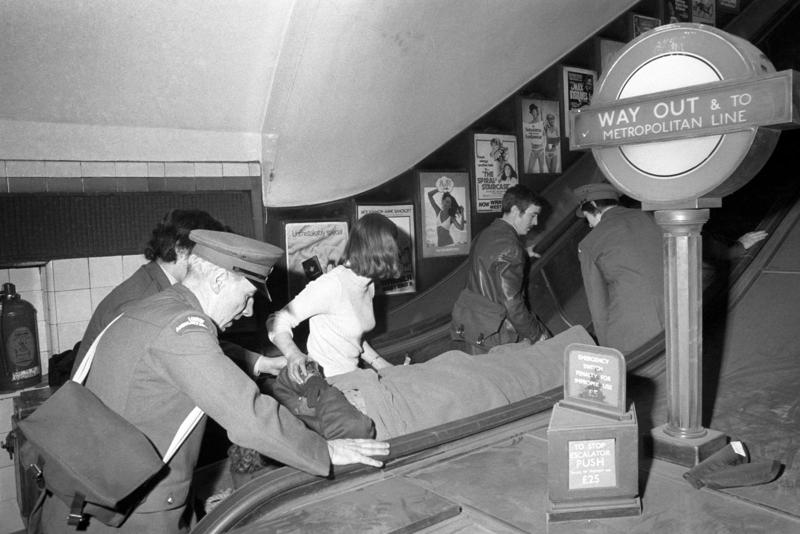

It wasn’t until late on the Friday evening that the last two survivors were brought to the surface. One was a young policewoman who had been so badly trapped that the only way to extract her was to amputate her foot - a hugely tricky operation in the confined space.

Once all the survivors were accounted for, the rescuers started on the gruesome task of recovering the dead. Most were in the front two cars, as these were closest to the platform exit. It took four days to remove all the corpses.

When I returned to work on the Monday morning, the operation was still very much in progress.

The station was still completely closed to passengers, with Northern Line services suspended and trains on the sub-surface lines running through without stopping.

By now, a new worry had emerged. With the rescuers working close to so many dead bodies, there was fear of disease taking hold.

As men emerged from the tunnel, they were being ordered to remove their boots and outer clothing for disinfecting, and to wash their hands and faces in buckets of disinfectant. Those who had received cuts from the jagged metal were given anti-tetanus shots. Later in the day, a mobile army decontamination unit arrived to assist with the task.

The station reopened on the Tuesday of the following week, 12 days after the crash. On that day, I resumed my normal commute into Moorgate, arriving at about the same time that the accident had occurred.

This time, I was aware of a media presence at the exit from Platform 9. London Transport officials were meeting arriving passengers, asking for anyone who had been in the crash to come forward to give evidence at the inquiry.

The inquiry got under way shortly afterwards. Led by Ian McNaughton, Chief Inspector of Railways, it delivered its report in March of the following year. But despite hearing evidence from more than 50 experts and eye witnesses, it failed to identify with any certainty the cause of the accident.

The press made a big thing of the fact that the train was nearly 40 years old. But the 1938 stock was still the workhorse of the Tube system, reliable and with an excellent safety record. No fault was found in the brakes or traction equipment on the crashed train. Nor were any issues identified with the track or signalling.

The inquiry concluded that “the cause of this accident lay entirely in the behaviour of Motorman Newson”.

But it did not suggest what that particular behaviour might have been. Suicide, alcohol consumption, even simple day-dreaming - these were all considered but ruled out.

Nor had the post mortem on Newson’s body revealed any illness or other physical condition that might have prevented him from applying the brake, although after four days in the oven-like heat of the wreckage, the body was so badly decomposed as to make any reliable post mortem results unlikely.

Unlike the 1987 King’s Cross fire or the 1999 Ladbroke Grove crash, Moorgate revealed no structural or organisational failings on the part of the operator, no lack of training of the staff, no disregard for established rules or procedures. On the contrary, McNaughton explicitly stated that no part of the responsibility for Moorgate rested with any person other than Newson.

The inquiry did, however, make one significant criticism of London Transport (LT). Described by The Times as an “extraordinary loophole in [LT’s] safety system”, there was no automatic mechanism in place to slow or stop a train entering a dead-end terminal platform at speed.

The Underground has always deployed tripcocks as a defence against SPADs (signals passed at danger).

If a driver passes a signal at danger, the mechanism automatically applies the brake. But that wouldn’t have helped in this case. The only relevant signal at Moorgate was the one protecting the crossover at the entrance to the platform, and this was correctly set clear.

Following two earlier incidents (one of them fatal) in which empty trains had run into buffers in a reversing siding at Tooting Broadway, LT had introduced time-release train stops in all of its sidings.

These were designed to halt a train passing the device above a given speed before it reached the end of the track. But there had been no plans to install this type of protection in terminal platforms on the passenger network.

All that changed after Moorgate. LT immediately introduced a 10mph speed limit in all dead-end terminal platforms. It then installed time-release switches along all the relevant platforms. If a train passed any of these switches at more than 12.5mph, it would immediately be brought to a halt.

As McNaughton pointed out, this would not completely eliminate the possibility of a Moorgate-style crash, as the motorman could still theoretically release the brake and accelerate the train. But it would be extremely unlikely.

Today, Platform 9 at Moorgate (where the accident occurred) and the adjacent Platform 10 are no longer part of the Underground.

In October 1975, the Northern City branch was handed over to British Rail, as had been previously planned. It is now used by Great Northern electric services from Welwyn Garden City and Stevenage.

Outside the station, there are two reminders of the terrible events of that Friday morning: a small memorial plaque on the side of the station building in Moor Place; and a larger memorial, listing the names of the dead, in nearby Finsbury Square.

The Moorgate disaster remains the worst ever train crash on the London Underground. The subsequent rescue and salvage operation involved 1,324 firefighters, 240 police officers, 80 ambulance workers and a huge number of doctors, nurses, LT breakdown crews and volunteers from the WRVS, the Women’s Transport Service and the Salvation Army.

Even now, 50 years later, it seems certain that its cause will never be definitely known.

For a full version of this article with more images, Subscribe today and never miss an issue of RAIL. With a Print + Digital subscription, you’ll get each issue delivered to your door for FREE (UK only). Plus, enjoy an exclusive monthly e-newsletter from the Editor, rewards, discounts and prizes, AND full access to the latest and previous issues via the app.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.