In August, Ukraine signed a deal with the European Union on harmonising its railways with those of its western neighbours.

A month or so before that came news that a subsidiary of Ukraine’s state railway company had gained a licence to run in Poland.

In August, Ukraine signed a deal with the European Union on harmonising its railways with those of its western neighbours.

A month or so before that came news that a subsidiary of Ukraine’s state railway company had gained a licence to run in Poland.

And back in April, Ukraine’s Prime Minister looked on as the first dual-gauge track panels were laid on a line that will allow standard-gauge trains to run 14 miles into the country to Uzhgorod - rather than having to change gauge at the borders. This ‘Eurotrack’ will run to Chop, meeting railways from both Hungary and Slovakia.

Ukraine is turning to the West - physically as well as emotionally. That initial ‘Eurotrack’ is about freight, but in future the country is to be connected to the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T), allowing passenger trains to run directly from cities across the continent.

All places are prisoners of their past - that’s a cliché, but one that seems particularly apposite to Ukraine right now. Its history as part of the Soviet Union meant that the bulk of today’s Ukrainian railways were built to 5ft (now 1,520mm) gauge rather than the 4ft 8.5in (1,435mm) that spread from Britain around much of the globe.

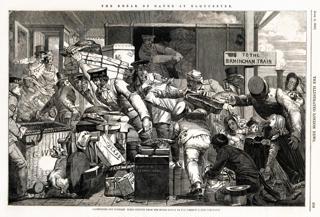

In fact, however, Ukraine’s first railway was both standard gauge… and British.

It is also claimed to be the world’s first military line, and was built by engineer Thomas Brassey in 1855.

The 14-mile Grand Crimean Central Railway supplied Sevastopol and lasted just a couple of years, with the track lifted and sold to Turkey after the Crimean War ended.

The first permanent line was constructed in 1861, connecting Lviv with Cracow (Poland) and Vienna. By 1914, Ukraine had approximately 15,600km (9,690 miles) of railway.

During the inter-war years (when Ukraine became the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic), the network expanded to include lines that had been planned before the First World War, adding a further 4,000km (2,485 miles) to the network.

Damage during the Second World War was extensive. Then in 1945, Western Ukraine, not under Moscow’s control before the war, was incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Crimea was added in 1954.

Although several of the early cross-border lines were standard gauge, Ukraine’s main network was built to ‘Russian gauge’. Electrification and track doubling took place from the 1950s.

Upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Ukrainian Cabinet formed the ‘State Administration of Railway Transportation in Ukraine’, which proclaimed Ukrzaliznytsia a government body administering railway transportation, uniting the six state railway directorates of Donetsk, Dnipro, Southern, Lviv, Southwestern, and Odesa.

The early 21st century brought a reconstruction programme, with stations refurbished and new express trains introduced.

In February 2014, President Viktor Yanukovych was deposed after halting plans for economic alignment agreement with the EU. Ukraine’s parliament had approved finalising the agreement, but Russia had pressured Ukraine to reject it.

On February 27, Russian soldiers without insignia invaded Crimea. A disputed referendum on seceding to Russia was held, with Russian military overseeing the voting, resulting in an alleged 97% in favour. Later that month, Vladimir Putin ratified a law incorporating Crimea into the Russian Federation.

At the same time, receiving covert support from Russia, militants in Ukraine’s east took over towns in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions (known as the Donbas). Ukrainian attempts to fully retake these areas failed, and disputed independence referendums were held by Russian authorities.

During the winter of 2021-22, there was a build-up of Russian military along the Ukrainian border and in Belarus. In February 2022, Russia recognised the independence of the self-proclaimed people’s republics of Donetsk and Luhansk and ordered troops into the territories as “peacekeepers”. On February 24, Putin announced a “special military operation”. Within minutes, explosions were heard in major cities across Ukraine.

Ukraine’s airspace was closed to civilian traffic at the start of the invasion, owing to the threat of missile attack. Ukrzaliznytsia (UZ) reported a large increase in passenger numbers, which included evacuating people from conflict areas.

Russia’s initial advances to the outskirts of the capital Kyiv and Ukraine’s second largest city Kharkiv were quickly pushed back by the Ukrainian army, who regained most of the territory.

The UN reported that more than a million refugees fled Ukraine in the first week of the invasion, reaching over eight million by February 2023. A significant number have returned, especially to western and southern regions away from the conflict zone, with around eight million people still displaced.

The vast majority of refugees have moved by rail - 61,000 people were evacuated by train from front line regions in 2023. The railways have taken on the increased workload along with several other new roles, including military traffic and carrying politicians and other dignitaries to Kyiv for meetings. Evacuation trains returning empty from the west were utilised to deliver humanitarian aid back to the affected regions.

Initially, Russia was not targeting critical rail infrastructure, assuming it would take control of the country quickly and depend on the rail network. After the Ukrainian counter-offensive a significant amount of damage has been inflicted by retreating ground forces and air attack, with a large number of casualties among railway workers. To date, 684 railway workers have been killed and almost 2,000 wounded, with 460 losing their homes.

Missile and artillery attacks on the network have also killed dozens of civilians and caused extensive damage.

The Kyiv School of Economics estimated that by September 2023, Russians had damaged $4.3 billion (£3.6bn) in railway infrastructure and rolling stock, and UZ has stated that around $16bn (£12.2bn) is needed for reconstruction work, including several major bridges.

Across the north and east, UZ has restored services to more than a dozen liberated stations. In November 2022, passengers arrived in Kupyansk in the Kharkiv region a month after it was liberated.

Oleksandr Kamyshin, the 38-year-old chief executive of UZ, declared: “We have a rule. Our tanks go in first, followed by our trains. Once our troops reclaim our territory, our job is to restore rail service there as quickly as possible.”

UZ has said that damage to the network is being repaired quickly where possible, although some infrastructure takes longer. Two major bridges were destroyed, and reconstruction is a multi-million-euro project.

As of June 2024, 83 bridges have been destroyed (and 46 rebuilt), 25km of track has been replaced of 52km destroyed, and 2,000km (1,242 miles) of overhead line equipment has been damaged and destroyed, but 700km has been repaired.

There has been a wide variety of aid delivered to Ukraine, including from the railway industry to UZ.

The Global Ukraine Rail Task Force is organised by Allrail, an association of independent passenger rail companies based in Brussels. It was established to support Ukrainian railway employees and their families, as well as to aid in rebuilding railway infrastructure, and improving passenger and freight capacity levels.

They raised €300,000 (£252,000) to purchase 13,000 food and drinking water packages that were delivered to railway workers and their families at the frontline and in newly liberated territories.

Rail Partners, which represents private rail operators in the UK, has fundraised more than £106,000 in donations to support Ukrainian rail workers, and has visited Ukraine as part of an official delegation to see how the European rail industry can best help Ukraine. Rail Partners is currently running the Kit for Kyiv campaign, fundraising for body armour for Ukrainian railway workers.

A team of volunteers from Network Rail delivered four vehicles - loaded with spares and railway tools, including generators, drills, jacks, and cutting equipment - to UZ in May 2022, all the equipment having been donated by NR.

Also in 2022, a train of 24 shipping containers filled with aid was delivered to Ukraine after being transported across Europe by DB Cargo. The aid was organised by UK Rail for Ukraine, a group comprising volunteers from across the railway industry.

In February 2023, NR donated £10 million worth of bridging material, including rapid-build modular steel bridges and tunnel-lining repair equipment provided by Mabey Bridge.

Deutsche Bahn transported aid to Ukraine free of charge soon after the invasion in 2022, but dropped the service in March 2023.

United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) has delivered a variety of equipment as part of its RELINC project (Repairing Essential Logistics Infrastructure and Network Connectivity).

In August 2024 it delivered 200 flatbed container wagons to UZ, and between December 2023 and July 2024 it delivered over $8 million (£6.1m) worth of plant equipment to Ukrainian Railways - including excavators and dump trucks, as well as smaller items such as compressors and concreting equipment that are crucial for repairing damaged lines and infrastructure.

The management of UZ has started to plan the reconstruction and development of the organisation and the network, some of which is reconstruction of damaged existing infrastructure, along with improved facilities for disabled people, and high-speed standard gauge lines to improve connections to the rest of Europe.

A joint paper published by the World Bank, UZ, the EU and UN estimates that the railway network needs a budget of €16.6bn (£14bn) for recovery and reconstruction work over a decade.

This is in addition to the substantial amount needed for improved connections to the rest of Europe. One of the biggest hurdles is the break of gauge, as Ukraine (along with Moldova) uses Russian 1,520mm gauge.

In July 2023, the European Commission and European Investment Bank produced a detailed joint study regarding the integration of Ukrainian and Moldovan railway networks with the existing European standard gauge networks. Agreements to extend four European Transport Corridors into Ukraine and Moldova were ratified in April 2024.

The proposal is to develop routes of the TEN-T core network to include direct international connections to Lviv from Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania, a direct international connection to Odesa from Moldova, a line connecting Lviv and Odesa, and a line connecting Lviv, Kyiv and Mariupol.

Ukraine is a significant producer of grain for the global market, and the traditional route for most of its grain exports (which total around 45 million tonnes a year) was via the Black Sea ports of Odessa, Yuzhne and Chornomorsk.

To facilitate exports, an agreement known as The Black Sea Grain Initiative was implemented by the UN, Turkey, Ukraine and Russia in July 2022, although it expired around a year later when Russia refused to renew the agreement.

After the expiry, Russia attacked many of Ukraine’s main grain export ports with missiles and drones. Odesa has been a primary target, while the smaller river ports in Reni and Izmail (on the river Danube in the west of Ukraine) have also been targeted.

Much of the grain exported by Ukraine is destined for Europe, China and Africa, and the issues of grain supply have been discussed on a global basis, with concerns regarding food security owing to the volume of Ukrainian food production and export.

In the trade year 2022-23, Ukraine was the sixth largest wheat-exporting region, producing around 5% of the world’s wheat. Other food commodities exported include nearly 40% of global sunflower meal exports and 35% of sunflower oil production.

UZ itself set up an operating company in Poland named Ukrainian Railways Cargo Poland, headquartered in Warsaw.

Having received a licence to operate at the end of June, it is now able to focus on increasing freight volumes through Polish-Ukrainian border crossings for export traffic to Polish ports on the Baltic Sea, or further west to the German ports of Hamburg and Bremerhaven on the North Sea coast.

UZ chairman of the board Yevhen Lyashchenko says: “Obtaining the licence is another step on the way to creating a fully-fledged international railway operator that will be able to offer its customers a single cross-border transport service. We are also working on the development and co-ordination of new international routes.”

In May 2023, UZ agreed to co-operate with Lithuanian Railways (LTG) in the Free Rail programme, to strengthen business ties among the Baltic countries and Ukraine. It is unclear how this will incorporate in the Rail Baltica Programme, which is a high-speed line that will connect Warsaw with the capitals of the Balkan states, and which is in the early stages of construction.

The European Commission produced an action plan for EU-Ukraine Solidarity Lanes to facilitate Ukraine’s agricultural export and bilateral trade with the EU in April 2022.

This implemented a “match-making platform” to facilitate exchanges between logistic chain operators to optimise cargo flow from Ukraine to the EU and further afield, emphasising the importance of grain exports.

EU wagon owners were hesitant to allow their rolling stock and vehicles to enter Ukraine after the invasion, but in 2022 the Ukrainian government published a decree that allowed for compensation to cover the cost of damaged wagons.

Previous grain movements west by rail led to unintended consequences, with some being sold in Poland and Romania, leading farmers there to object owing to the lower price than domestically produced grain. During some isolated incidents in the winter of 2023-24, trains were halted at the border and grain tipped out on the track by protesters.

The Polish, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Slovakian and Romanian governments effectively banned the sale of Ukrainian grain and several other agricultural products in their countries, while assisting with rail transport to ports - enabling it to be exported.

This approach is not universally popular with Ukraine or the European Union, but it appears to be a pragmatic solution which allows for the export trade to continue.

One such measure to enable the flow of grain for export was the opening of Europe’s largest railway grain trans-shipment terminal in the Romanian town of Dornesti in May 2024. This will handle three million tonnes of grain annually to streamline traffic to Constanta, a major Black Sea port in southern Romania.

Spain’s experience with gauge-changing bogie technology is also being utilised. Spanish infrastructure manager ADIF is piloting the use of automatic gauge-changing wheelsets with UZ - the technology allows automatic changing from Spain’s traditional 1,668 mm gauge to standard gauge and is being adapted to add 1,520 mm gauge capability.

UZ has stepped up domestic production of wagons and components, as it imported a substantial number from Russia before the invasion. The UZ wagon works are now building newly designed variable gauge hopper wagons.

This is the first time UZ has ventured into variable gauge vehicle production, and Lyashchenko notes: “Next, we plan to put such wagons (the new hoppers) into serial production.”

It has been noted in various reports that gauge changing technology, while enabling freight volumes to be increased relatively quickly, is not a longer-term option. There is a considerable difference in loading gauge between Ukraine and EU countries.

Grain hoppers in Ukraine have a maximum volume of 104 cubic metres and measure 14.7 metres in length, 3.2 metres wide and 4.8 metres high. The rest of Europe operates grain hoppers with a volume of 102 cubic metres and are 15.4 metres long, 3.1 metres wide and 4.2 metres high.

UZ Board Member Yevhen Shramko stated in August 2023 that UZ “was already looking into the design of grain hoppers with EU-compatible dimensions. However, there are other significant bottlenecks to integrating the railways besides the gauge issue. For example, testing methodologies in Ukraine are quite different from the ones in Europe.”

Until the start of the war, virtually all rail used in Ukraine was manufactured by Azovstal Iron and Steel Works in Mariupol, which fell into Russian hands in May 2023 after a three-month siege. Other sources have now been agreed from outside the country. The French government has agreed a €37.6m (£31.6m) loan to Ukraine for rail from French manufacturer Saarstahl Rail, which will supply around 20,000 tons of rail in 2024. The loan extends for 35 years, with a 14-year grace period.

The first batch of rail gifted from Japan arrived in May, with the remainder of the 25,000-tonne consignment to be delivered by the end of 2024. The deal is brokered by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (Jica) on behalf of the Japanese government’s Emergency Recovery Programme.

Lyashchenko notes: “We need 70,000-100,000 tonnes of rail every year just for repairs. We plan to use the rail received from Japan to repair the main lines from Kyiv to Lviv, Odesa, Uzhhorod and Dnipro.”

Some development and construction of improved connections is already under way. A new standard gauge electrified connection between Chop (south-west Ukraine) and Uzhhorod (western Ukraine) is currently under construction, continuing the standard gauge line that crosses from Hungary. It is planned to continue the link to Lviv and electrify the entire length.

In January 2023, the broad gauge connection between Dilove (south-west Ukraine) and Valea Viseului (Romania) was reopened. Out of use since April 2006 owing to serious flood damage, the connection now serves as an alternative route to Romania instead of the vulnerable Zatoka bridge in Odesa.

Private operators are also developing better connections to Ukraine, with Regiojet introducing a new Prague-Kosice-Chop Sleeper service in March 2024, while Metrans started a freight service between Medyka (Poland) and Mostyska (Ukraine) in May.

International involvement in Ukraine has unsurprisingly increased since 2022, with the railways no exception.

In November 2023, UZ signed a Memorandum of Understanding with South Korean rail operator Korail and Korea National Railway for co-operation on seven reconstruction projects.

They include a high-speed railway between Ukraine and Poland, an increase in capacity of the existing railways connecting the southern cities of Reni, Odesa and Izmail, and construction of a new railway traffic control centre.

Hyundai-Rotem is expected to supply rolling stock. Its ten HRCS2 nine-car Rotem units are already in service on UZ (since 2012), where they operate higher-speed services on the Lviv-Kyiv-Kharkiv routes.

In December 2023, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) signed a Memorandum of Understanding with UZ to assist in developing a 75km (46-mile) dual gauge line from a connection with the existing standard gauge line at Mostyska in Poland, to run parallel with the existing 1,520mm gauge line to Sknyliv about ten kilometres west of Lviv city centre.

The development, with a proposed $225m (£171m) of funding from USAID, will include a freight facility and passenger terminal at Sknyliv to relieve pressure on Lviv central station. The connection will also add freight capacity.

USAID has calculated that improvements to land and rail border crossing points could increase grain export capacity by an estimated 2.5 million metric tonnes per year, boosting exports by up to $425m (£324m).

In addition to the hurdles UZ has had to overcome as a result of the invasion, it is now facing another potential problem with finances.

In August, it announced that it is now facing financial issues owing to a court ruling regarding freight tariffs. According to the company, several private companies in a “large industrial group” succeeded in annulling a 2021 government decision to raise rail tariffs, when the Ministry of Infrastructure changed the tariff coefficient from 2,204 to 2,402 for First Class cargo. This class primarily includes raw materials.

The Kyiv court is now also looking into two more related cases, says UZ, which is appealing the court’s annulment of the 2021 tariff decision. It argues that the court did not evaluate the legality of the measure, but rather the political expediency of it, and that the court overstepped its boundaries.

There are a number of European freight companies keen to be involved in handling the €45bn (£38bn) worth of Ukrainian exports annually, and the railway industry worldwide has already shown a strong commitment to assisting Ukraine with developing its network and international connections (although more is needed).

Russian aggression towards Ukraine and its plans to bring Ukraine back into its fold have spectacularly backfired, and the Ukrainian people have shown that the vast majority now want and seek closer ties to the rest of Europe. The railways are a key part of this.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.