Philip Haigh joins one of Network Rail’s video inspection units, to learn how the technology is improving detection, efficiency and safety.

Philip Haigh joins one of Network Rail’s video inspection units, to learn how the technology is improving detection, efficiency and safety.

The next train to leave Platform 17 is the 1039 to… Platform 15.

Sure enough, at 1039, Class 153 153385 departed and ran the few hundred yards into Liverpool Street station throat, and then into Platform 15 after its driver changed ends.

Of course, there was no public announcement of this move, nor of 153385’s several more visits to Liverpool Street that morning as it shuttled back and forth over the final few miles of the Great Eastern Main Line.

The unit is one of Network Rail’s fleet of three video inspection units (VIUs), equipped with forward-facing cameras and a second battery of linescan cameras slung underneath to record the state of the track in millimetre detail. It also records track geometry via sensors fitted to its bogies. All at up to 70mph.

RAIL joined November 6’s run, which would take the ‘153’ as far out as Temple Mills, around six miles from Liverpool Street.

The unit usually has just its Colas Rail driver, with its former passenger interior stripped out to house a diesel generator, computer racks, batteries and modems. It retains a couple of bays of seats and tables, as well as basic mess facilities. The unit records and uploads images automatically, sending typically half a terabyte per shift.

NR Infrastructure Monitoring Project Manager James Lee explains that NR visually inspects switches and crossing (points) across the network around every two weeks, looking for cracks, damage or other problems.

Following recent accidents, NR has banned ‘red zone’ working which would see inspections taking place on open lines as trains ran.

The alternative of closing lines while checks took place during daylight would have disrupted train services too much, while night-time inspections risked not seeing problems, so NR turned to other answers.

Mounting cameras on a ‘153’ proved an answer because it takes little time for the driver to change ends and reverse direction (not needing to climb onto the track to do this). It could therefore shuttle back and forth across the pointwork of somewhere like Liverpool Street with comparative ease.

But that still means threading it between passenger services, and Lee says it has been challenging to find working timetable paths that permit this on a regular basis. (November 6’s trip is the first at Liverpool Street, so is also to prove to NR’s System Operator that its timetable path works.)

For the moment, NR continues manual inspections while it grows confidence in the automatic product, which is reviewed by the same technicians as carry out the manual checks. Eventually, NR will cease manual checks in favour of reviewing the VIUs’ material.

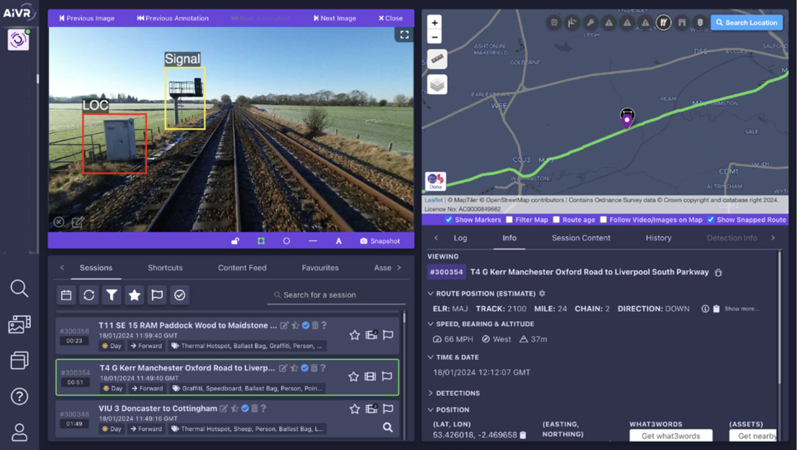

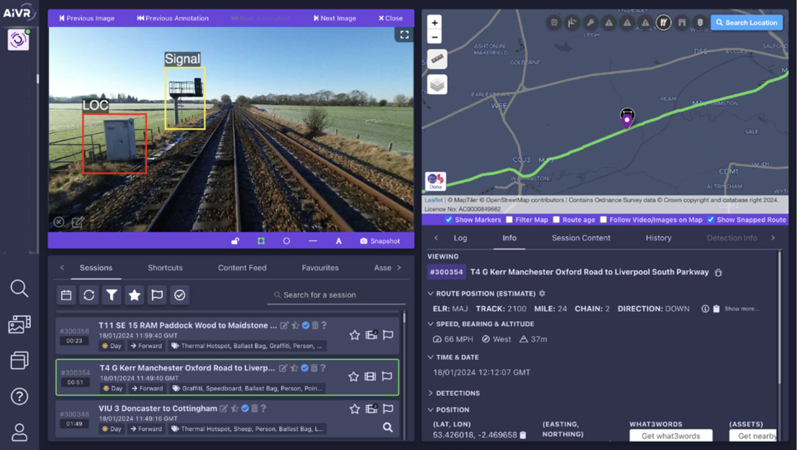

NR uses One Big Circle’s Automated Intelligent Video Review (AIVR) system, to take the time out of these reviews. AIVR uses machine learning to identify and classify what the cameras see.

Logging into AIVR through a web browser allows the user to see video recordings of a route, captured by the VIU fleet’s forward-facing cameras. This could be ordinary visual recordings or thermal recordings to detect hot spots such as electrical faults, or to see if point heaters are working correctly.

Or the user can ask AIVR to show every signal along a stretch of line. Or every speedboard. Or scrap rail. Or location cabinet. Even graffiti.

The thermal imagery could pull up every hotspot along a route. Or AIVR can generate an automatic alert when it finds a hotspot that might, for example, be the symptom of an electrical fault.

From these videos, users can deploy basic measuring tools, saving the need to send someone out to check something.

These tools are not approved for design work, One Big Circle’s Jasper Roseland tells RAIL, but they’re good enough for rough, initial work.

The VIUs’ underslung track cameras use similar machine learning to identify components and faults, even showing up hairline rail cracks, according to Lee. It can find rail joints, measuring the gap between rails on jointed track, for example.

AIVR can find and read casting marks on switch and crossing components, which Roseland suggests can be easier than finding the drawings that have this information.

Seven cameras sit under the ‘153’. One concentrates on the four-foot space between the rails, while each rail has three cameras - one vertical and two angled to see both sides of the rail.

AIVR can find squats (which are defects on the railhead), or contamination, missing ballast, wet spots, or many of the host of track faults a visual inspection team would be expected to detect.

And with repeated runs, AIVR makes it easier to see how something is changing, enabling technicians to monitor developing situations, and allowing them to act before something becomes a problem.

For all the system’s automation, the state of the track remains an engineers’ responsibility, with them making decisions on work depending on what they see.

Repair work still needs to be carried out, usually at night when tracks can be closed. But with inspection trains such as NR’s Class 153s, these closures can spend more time on repairs rather than devoting time to inspections as well.

The underslung cameras record the railway in one-millimetre slices, presenting images with no blurring. Precise location information comes from a combination of GPS data and video interpretation from a company called Machines With Vision.

At its simplest, this uses known visual characteristics such as cracks and marks on sleepers to give precise locations, often to better than 10cm accuracy.

The trains literally take the legwork out of basic visual track inspections, while the AIVR software bring consistent analysis without the risk of missing problems.

“It doesn’t get bored like humans,” Roseland notes, although he adds that it’s not perfect. It sometimes confuses scrap rail lying in the four-foot with guard rails on bridges, for example.

NR currently has three VIUs - 153311, 153376 and 153385 (which is RAIL’s ride for November 6) - working on its Eastern (one unit) and Southern (one on Wessex and one on Sussex) regions. NR leases them from Porterbrook. Colas Rail operates them, and Loram maintains them.

From next year, they will be supplemented by two more VIUs (153383 and a second that has yet to be identified), according to Lee.

So far, the VIUs have concentrated on the track. But one has a pair of cross-eyed cameras on test that concentrate on structures. Lee reckons this equipment will come from new on VIU4 and VIU5.

There is also a pair of track condition monitoring units (TCMUs), 1533379 and 153384, which will supplement NR’s plain line pattern recognition trains on Eastern and Anglia.

NR’s fleet of Class 153s, painted blue rather than the usual track yellow, marks a major shift in the way the company assesses what work is needed to keep its railway in good condition. That’s good news for passengers, freight users and funders alike.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.