In the second in our series of extracts from Bradley’s Railway Guide: A Journey Through Two Centuries of British Railway History 1825-2025, we look at Rammell’s Pneumatic Railway - and developments since.

The past: 1864

In the second in our series of extracts from Bradley’s Railway Guide: A Journey Through Two Centuries of British Railway History 1825-2025, we look at Rammell’s Pneumatic Railway - and developments since.

The past: 1864

The failure of Brunel’s atmospheric railway did not put an end to attempts at developing railways powered by means of pumped air.

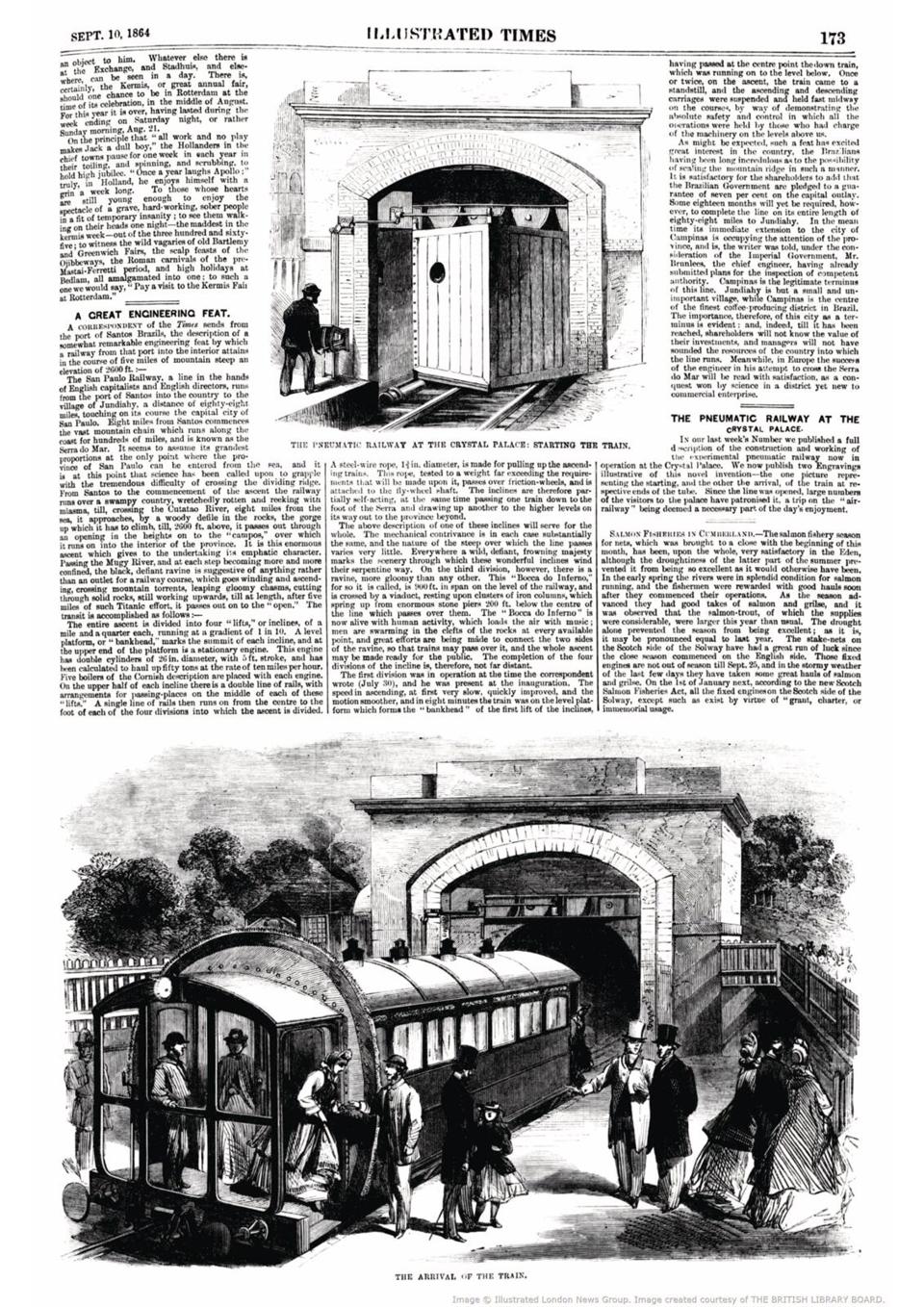

One project that did achieve limited success was the Pneumatic Railway devised by the engineer Thomas Webster Rammell (1814-79). This operated in 1864 in the park at the Crystal Palace in South London, where the Great Exhibition building (1851) had been reconstructed as a permanent attraction.

Some 600 yards long, the railway was enclosed within a curved brick- built tunnel, and rose at a sharp gradient of 1-in-15. The air supply was generated by a giant fan-wheel, powered by a stationary steam engine and acting on a single carriage with room for up to 35 passengers.

To ensure a tight seal, a rounded timber diaphragm edged with bristles was attached to the carriage, rather like a giant rigid flue brush. In addition, each end of the tunnel could be sealed by a folding door.

To get the carriage moving uphill, the fan blew air into the tunnel, pushing the vehicle along on the pea-shooter principle. A briefer reversal of the air pressure, acting through a duct at the upper end of the tunnel, got the carriage moving on the downhill journey.

Rammell’s Crystal Palace railway was intended as a demonstration, and was in use for only a few months.

It represented an attempt to scale up the technology used by the London Pneumatic Despatch Company, which had opened its first tunnel route the year before.

The company carried parcels and post in small narrow-gauge wagons between railway termini and sorting offices, but unreliable operation and the relatively modest time savings compared with street-level transport led the Post Office to abandon its use in 1874.

Yet in 1864 the concept still appeared to many to have a great future. Admiring press reports of the Crystal Palace installation stressed its smoothness of movement and the appeal of breathing clean air within the tunnel.

Rammell’s next step proved to be a tunnel too far. The Whitehall & Waterloo Railway, begun in 1865 and abandoned incomplete in 1867, remains surprisingly little known for such a bold project.

It required the construction of a sunken iron tube below the Thames, comprising lengthy segments 12 feet in diameter. These were to be linked together by brick chambers built below the level of the river bed.

Beyond the underwater section, the line would have continued to Old Scotland Yard at the upper end of Whitehall, and to Waterloo station, where the pumping apparatus to blow and suck the trains back and forth was to be constructed.

There was even wild talk of extending the line southwards as far as the Elephant & Castle, more than doubling its length. Work stopped on account of a shortage of funds, so the technology never had a chance to prove itself.

In the event, the world’s first operational Tube railway did not open until more than 20 years later, with electricity as the transformative power (1890).

■ Reproduced with permission from Bradley’s Railway Guide: A journey through two centuries of British railway history, 1825-2025 by Simon Bradley (Profile Books, £30).

The Present: Hyperloop and other dreams

“With the atmospheric system, Brunel had taken the power source off the engine and put it in a pumping station in much the same way that modern electric locomotives take their oomph from a power station.”

Jeremy Clarkson eloquently argues that Brunel’s atmospheric system should be given greater consideration in the story of Britain’s railways, rather than being an embarrassing footnote. He adds: “Brunel’s problem was that he was thinking 21st century thoughts in a 19th century world.”

Brunel hasn’t been the only engineer whose ideas were hampered by the technology available to hand. While it’s doubtful that Leonardo Da Vinci’s ornithopter would get off the ground (no pun intended!) with today’s technology, a version of Thomas Webster Rammell’s Pneumatic Railway is being developed.

Today’s version is called a hyperloop. It’s a glorified version of the ‘tube travelling technology’ beloved by science fiction writers for decades. But real hyperloops have been built, to the point that papers setting common standards have been published.

There have been many attempts to replace the flanged wheel-on-rail that has served the railway well. Christopher Cockerell’s invention enabled a machine to travel on land just as easily as it could travel on water. Could hovercraft technology be applied to a train? Displayed alongside the Nene Valley Railway’s Peterborough terminus is the last remnants of Britain’s attempt to develop a hovercraft train.

Magnetic levitation (maglev) was deemed the logical next step. Magnets would provide a means to lift the vehicle away from the ground, reducing resistance and enabling ‘trains’ to run at high speeds.

The technology has been around for decades - as anyone who used Birmingham International Airport in the 1980s and 1990s can attest. But there are only seven operational maglev systems around the world today.

Thunderbirds still offers us a tantalising view of the future and, alongside atomic-powered airliners, monorails provide the main cross-country form of public transport.

Again, it’s not a new concept. The most famous monorail in the British Isles was the Listowell & Ballybunnion, built in County Kerry in Ireland, using the Lartigue system. Remarkably, while plans to build a monorail linking Liverpool and Manchester in the 1900s came to nothing, the nine-mile Listowell line survived until 1924.

Again, the monorail is a system that promises much but has yet to gain a true foothold.

Sydney’s was a case in point. It opened to great fanfare in 1988 but closed a quarter of a century later.

Of course, not all engineers found themselves in Brunel or Rammell’s position. George and Robert Stephenson had the skills and materials around them to build a working steam locomotive in 1825. Nigel Gresley was able to access the aeronautical and automotive research into wind resistance carried out in the 1930s, in order to develop the streamlined ‘A4s’ and thus create what was then Britain’s fastest locomotive.

BR has also been able to benefit from aeronautic research. Professor Alan Wickens brought experience from the aerospace world to better understand the high-speed wheel-rail interface.

From that research came the Advanced Passenger Train - a project curtailed not by the lack of available materials, but by the lack of money. But it wasn’t a wasted effort, for the High Speed Train emerged from the chaos.

It’s impossible to predict where the next invention or development will come from. It could be something radical that works. Or it could be another Pneumatic Railway.

But whether it’s fast-charging battery technology or communications-based signalling, our railways are constantly evolving.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.