In our latest extract from Bradley’s Railway Guide: A Journey Through Two Centuries of British Railway History 1825-2025, we turn our attention to the track.

The past: 1931

In our latest extract from Bradley’s Railway Guide: A Journey Through Two Centuries of British Railway History 1825-2025, we turn our attention to the track.

The past: 1931

Heavy locomotives such as the ‘Castle’ class could run safely at speed only when the railway’s track - the permanent way, in the industry’s terminology - was maintained to a high standard.

Even in the 1930s this upkeep was still carried on by the same labour-intensive methods used in the previous century. Track inspectors patrolled the line at regular intervals, monitoring wear and watching for defects, and gangs of men worked as directed with picks, jacks, levers and shovels.

One everyday task was to knock tightly into place the teak or oak wedges (‘keys’) that held the rails securely within their cast-iron supports (‘chairs’).

Another arduous routine was to pack the stone ballast firmly back under the sleepers, using a pick-like tool called a beater.

One modest innovation between the wars was the use of lightweight petrol-driven trolleys to carry inspectors and gangers up and down the line.

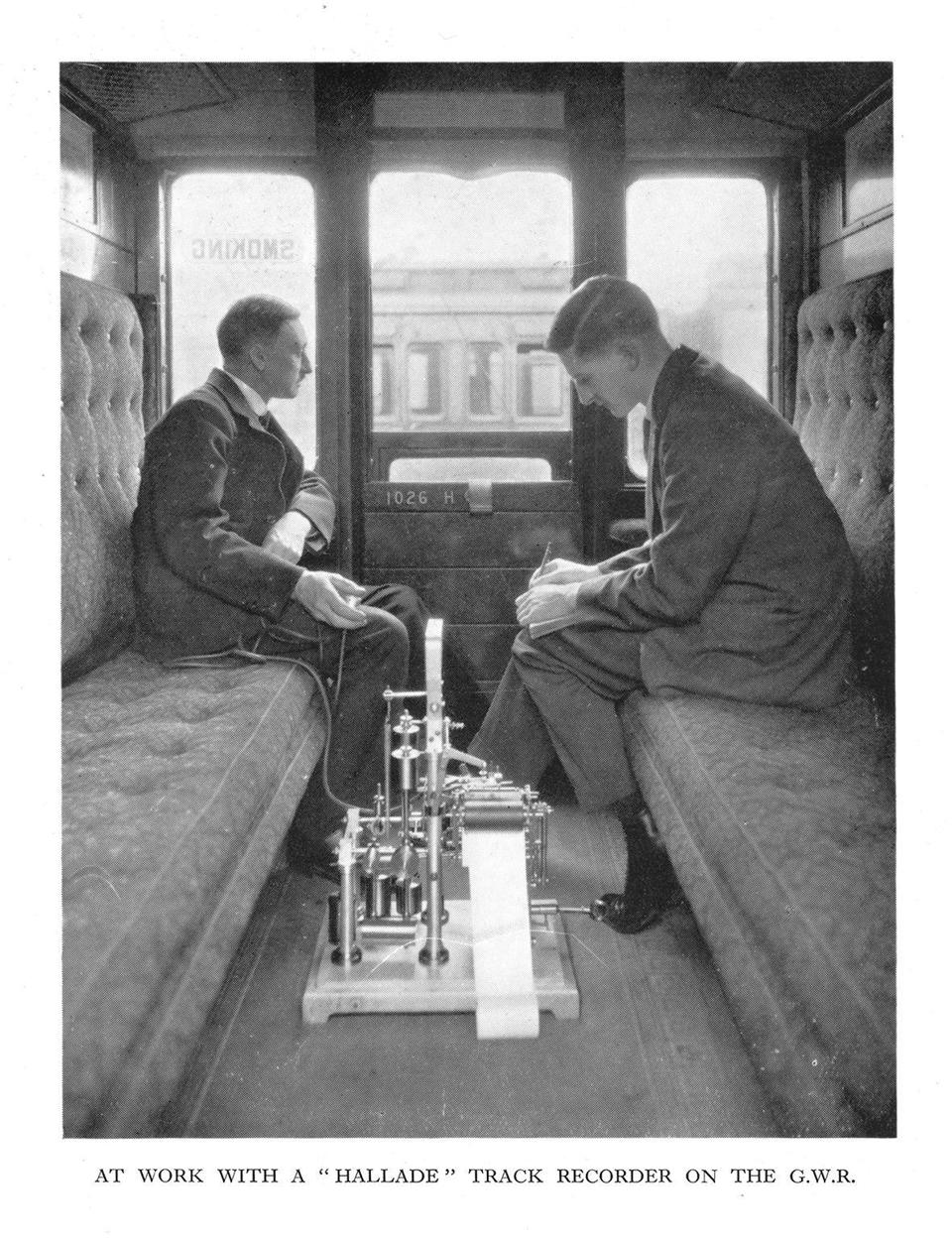

It was also possible to mechanise some of the inspector’s routines, thanks to the French invention of the Hallade track recorder. The Great Western was already using six of these machines by 1929, and in 1931 introduced a specially adapted coach equipped with two more.

The photograph, clearly posed, represents the Hallade recorder in ordinary use. This required nothing more elaborate than a standard railway compartment - the rearmost in the penultimate carriage of the train was the preferred choice - and two staff, an operator and a spotter.

The machine comprised a series of levers linked to pendulums, which responded to the train’s movements in different directions, and a clockwork-driven drum that passed continuous rolls of graph paper and carbon paper through the workings.

Pins attached to the inner ends of the levers left a record of jolts and oscillations, and a connected handset mechanism allowed the spotter to make a mark on the roll each time the train passed a landmark, such as a milepost or a station.

The completed roll thus served as a linear record of the state of the track, and could be scanned to identify defects for attention, such as a badly packed sleeper or a low rail joint.

An early publicity film has survived that shows the spotter wearing a robust face mask to protect his eyes from cinders and grit; the masked observer must have looked rather sinister to anyone catching a glimpse from the platform.

Hallade’s invention had a long life, and the special coach converted in 1931 remained in use into the 1980s.

Its other equipment included a tank of whitewash linked to a valve, which was calibrated to release two pints of the stuff when jolted by defective track. The unmissable white streak then pointed backwards to where the problem was.

Reproduced with permission from Bradley’s Railway Guide: A journey through two centuries of British railway history, 1825-2025 by Simon Bradley (Profile Books, £30).

The present: Digital monitoring and more

Richard Foster looks at how today’s NR New Measurement Train can do so much more, but technology is not standing still…

The Hallade track recorder fitted between two seats in a compartment. It’s a far cry from the technology that Network Rail deploys today, where there are entire trains full of monitoring and recording equipment.

Levers, pendulums and a roll of paper enabled the Hallade to record defects in the track.

By contrast, True Track (as used in NR’s New Measurement Train) uses lasers, gyros and potentiometers mounted under the train.

The resulting scanned, lasered image of the rails that the train is passing over is then fed to screens inside the train, where onboard technicians can see the twist (how parallel the rails are to each), alignment (how the tracks are moving left to right), the tops of the rails (monitoring dips and joints), gauge (how far the rails sit apart), cant and cant efficiency.

The train also boasts Plain Line Pattern Recognition (PLPR). This monitors every sleeper to make sure it has two rails attached to it, and that those rails are secured by two clips. It’s the train’s systems that monitors this, and will flag if something is amiss.

The NMT replaces visual inspections, whereby a team of engineers could cover somewhere between five and ten miles per night shift. By contrast, the NMT can cover 800 miles of track in a shift.

It also has ground-penetrating radar to study the sub-surface. It can also monitor the ballast profile, and can check that the GSM-R systems are working.

But the NMT doesn’t just look down. It can monitor the performance of the overhead catenary, too.

PLPR can monitor 14,000 miles of track every four weeks. This is bringing many benefits to Network Rail, for engineers can now predict where problems might occur long before the signs would be visible on a manual inspection.

This regular monitoring means that if a particular sleeper is losing its clips, it will be flagged as needing attention and a team of engineers can be despatched to investigate.

This is making the railway safer not only for those who use it, but also for the engineers themselves. Getting more ‘boots off ballast’ is a key part of NR’s Control Period 7 Delivery Plan (2024-29).

That said, time-served permanent way inspectors argue that there is still a place for physical interaction with the railway by skilled technicians.

But the NMT entered service in 2003, and CP7 funding has been secured for a team to look into the next generation of monitoring equipment, to replace or enhance what’s currently available.

History, however, could be coming full circle. Two of NMT’s Mk 3 coaches are full of recording and monitoring equipment. But advances in technology now mean that some monitoring equipment can be fitted to ordinary passenger trains, just as with the Hallade recorder. This will help Network Rail monitor even more miles of track - and we could see what this equipment looks like as early as 2027.

Unlike the Hallade recorder, with its rolls of paper, this will increase the amount of data that Network Rail has to process. But advances in computer technology will be able to sift through it all in order to highlight problems areas.

And while more ordinary passenger trains might be carrying more monitoring equipment, it won’t mean the end for specialist monitoring trains such as the NMT. These can run further and at the higher speeds that some monitoring jobs can’t do without.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.