Nine per cent of people working on the railway left last year. Many were retiring; some were attracted to other industries. Paul Clifton asks whether enough is being done to fill the empty seats they leave behind.

In this article:

Nine per cent of people working on the railway left last year. Many were retiring; some were attracted to other industries. Paul Clifton asks whether enough is being done to fill the empty seats they leave behind.

In this article:

- A large wave of early retirements—especially among guards, signallers, and driver managers—is threatening rail industry workforce stability.

- Skills shortages are worsened by funding delays, project cutbacks, and a shrinking workforce, particularly impacting Northern regions.

- Technological adoption and cross-sector competition are reshaping rail roles, requiring modern recruitment and retention strategies.

Four in ten guards are likely to retire by 2030. So are one in three signallers and driver managers.

They are retiring early. Network Rail says the average age of an employee at retirement is 62. But in some roles, it is down in the mid-50s.

This is far below the average age of retirement in the UK as a whole, and it presents the industry with a significant challenge: skilled staff on good salaries are heading for the exit in large numbers.

The data has been collected and analysed exclusively for RAIL by NSAR - the National Skills Academy for Rail.

“It’s all about the pension scheme,” explains NSAR’s Workforce Planning Adviser Neil Franklin.

“If you’ve been in the railway all your working life, you will be on a final salary pension. So, by the time you get to 55-ish, you will be eligible to retire - potentially on three-quarters of your final salary for the rest of your life.

“If you’re a train driver on £80,000 a year, you may be able to retire at 55 on £60,000 a year.”

Data analyst Sam Goody measured the railway working profile against people in the wider economy.

He says society “leans towards” using the age at which the state pension is paid as the standard point of retirement. For most, this is between 65 and 67.

“We divided rail workers into two groups. People with rail-specific skills, such as drivers and signallers, are less likely to be poached by other sectors. The others we label as skills-based roles, which we say are vulnerable not just to retirement, but to being poached by other sectors. People such as project managers and civil or electrical engineers.

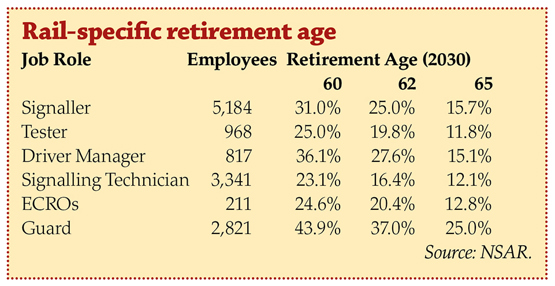

“Rail-specific workers retire earlier than ‘normal’ employees. The guards are the most likely to take early retirement, with 44% of these people reaching 60 years old by 2030. Driver managers and signallers both have more than one-third at 60 by 2030.

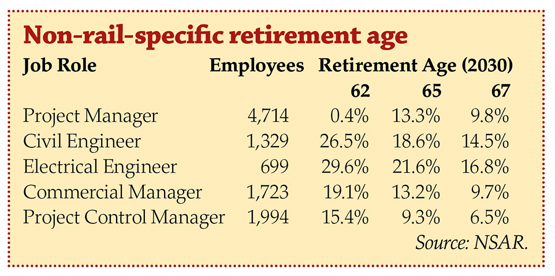

“For the skills-based roles not confined to the railway, electrical engineers are most vulnerable, with about 30% reaching 62 by 2030.”

Franklin notes: “People generally retire later in the skills-based roles that can transfer between sectors. They have moved around, they have changed employers, and therefore they are less likely to have the benefit of a final salary pension scheme.”

Goody assessed competition for workers from other sectors, using data from the annual population survey, which shows how many people are working in any particular occupation. From that, he can indicate how easy it would be to find more recruits to replace those retiring.

There are many electrical engineers and signalling technicians in the available pool, so replacing them should not prove difficult. But the number of civil engineers has fallen sharply this decade.

“We are just about keeping pace with driver recruitment,” says Franklin.

“I don’t think finding drivers is an area of risk, because people are attracted by the idea of driving a train and earning lots of money. There are hundreds of applicants for every vacancy.

“Signallers are in a different place. There is no doubt we are going to require fewer of them, because software will do a lot more of the work. So, we will not need to replace every retiring signaller like-for-like over the next ten years - technology will see to that.

“The retirement issue is a gloomy one for the railway. But you do need to add in the dimension of technology. This might force the accelerated adoption of tech in some areas, because the people won’t be available.

“So, in some areas this will become a story of modernisation rather than recruitment and retirement.”

NSAR Chief Executive Neil Robertson agrees: “The signalling engineering job will look more like digital engineering jobs in other sectors.

“We call that skills convergence. Look at the apprenticeships the supply chain is using to train rail people - instead of being railway with a bit of digital, now they are digital with a bit of railway. Which means there is greater competition for those workers, because they are qualified for many different sectors, and not just for rail as they would have been in the past. So, the stability among signalling workers will not be there in the future.

“As an industry, we will need to think differently about recruiting people, but also about retaining them.”

Interpreting the data

“I had a call this morning with all the HR directors in the supply chain,” says Neil Robertson.

“Nearly all the people in the supply chain are letting staff go or moving them around.

“There is a shortage of work. That is fact. So, there are surplus staff who are not being deployed, in areas where we know there is normally a skills shortage. They’re either being made redundant or a majority are being redeployed. Some are going overseas - that is fact, too.

“Those with an energy division are redeploying railway people there - moving them out of the rail sector.

“That’s because there are gaps in funding. The spending in the next five-year Control Period has been slow to start. HS2 procured their rail systems, but they don’t actually need them yet, because of delays to the programme.

“Nearly all the supply chain are cutting back. Very few are not.”

Office for National Statistics data shows a reduction in the total rail workforce from 740,000 in 2019 to 640,000 in 2023.

The Railway Industry Association, which represents the supply chain, calculates that more than 30% of that workforce is over the age of 50, with 47,000 people due to retire by 2030.

RIA’s annual survey of 250 rail business leaders showed that 83% expect a hiatus in the year ahead.

RIA told MPs on the Transport Select Committee: “Many companies are taking steps that will further reduce the rail workforce … forced to pause long-standing apprenticeship and graduate schemes.

“One key supplier has reported to RIA that they have had to make 660 employees redundant, including 172 highly skilled and experienced permanent signalling staff, due to unusually long delays in work coming through.”

More cuts are widely expected in the wake of the government spending review. With increased funding for defence, the Department for Transport is one area that could be ordered to go without.

“Our secret sources say they are modelling for a 20% reduction in spending at the Department. But a 10% reduction would appear more likely, with the money going to defence,” says Robertson.

“The reality is that the supply chain will have to do less work with less people. Less with less. The people who do the upgrading aren’t as busy as they expected to be.”

RIA Chief Executive Darren Caplan states: “We should not be planning for decline in this difficult moment.

“Passenger numbers are virtually at the same level as pre-COVID. A RIA-commissioned report by Steer last year forecast growth of between 37% and 97% to 2050, regardless of how supportive or effective the government’s policy towards rail is.

“The skills challenge is in part caused by the need to dramatically increase the numbers of people working in rail when there’s an almost certain requirement to increase rail capacity. And this is happening when the reputation of the railway is at a low ebb, due to strikes, poor service levels, and the negativity generated by the previous administration around HS2.

“So, it’s hard to attract new people in. This is not just a cost on government spend - it is an investment in jobs, innovation and skills, and generates a good £14 billion which comes back to the Treasury.

“What would help, more than anything, is a commitment to smoothing out the boom-and-bust pipeline of work. That is entirely within the gift of government, given the long-term nature of rail and the fact that you can see many years out what needs to be done and when.”

NSAR’s Robertson warns: “What’s going to happen is that we will do fewer upgrades and renewals, and the same amount of maintenance, so we will be patching and mending for longer. More sticking plasters on older kit.

“Performance and reliability will go down, and operating costs will therefore go up. In the near term, that will encourage ambitious people to look elsewhere for career progression.

“Presumably, the performance will become intolerable after a few years as the impact hits, and the government will then decide we have to invest again. Boom-and-bust returns.”

Robertson continues: “Layer in another factor. I’ve had two separate emails of despair from people involved with industrial strategy, because behaving this way will not make any meaningful redistribution of wealth, particularly in the North.

“The social value of railway jobs will not be there. The North gets nothing much from all this, although in some specific locations it will benefit from military spending. But just as the next election looms, it will become clear the North has gained little.

“I’m sure the Transpennine Route Upgrade will survive this, and so will East West Rail. But nothing else will.

“You will end up with a problem, and the workforce to solve it will not be there. People will have to be brought back, either through training or poaching, leading to wage inflation.

“If you have people not in work, that costs the Treasury a lot of money. More people on the dole. Putting more people in the military will not soak up the difference, for sure.

“That means there is a net drain on the economy. It is a short-sighted strategy, not providing jobs where they are most socially useful, in the North.”We’re not hearing this from the big companies in the supply chain. They’re not making the same complaints about workforce.

“Suppliers agree with what we’re saying,” insists Robertson.

“But they are not engaging with it. They are in redeployment mode. Managed decline, if you want to be tabloid about it.

“Because they are responsible employers, most of them are not stopping their apprenticeship programmes.

“But they must be tempted. The unions would question why they are taking on apprentices when, at the same time, they are making others redundant or not renewing contracts. We can see that demand for work is not where anyone expected, because government has delayed spending.

“Network Rail is really worried about this, and it is doing something about it. It has a big signaller training programme now. It gets many more applications for apprentices in the North than the South, per opportunity. That’s because there are fewer alternatives in the North, and maybe it’s because there is more respect in the North for traditional apprenticeships.”

The railway’s retirement picture

The rail industry will be posed a challenge by retirement in the coming years - in roles both specific to the industry, and in more skill-based roles where other sector competition may pose a threat.

In the case of the former, looking at the picture at the end of 2030, a role showing significant risk is the guard, where comfortably over 40% of employees would be of a notional retirement age of 60. Even given a more standard retirement age of 65, around a quarter of guards would be of retirement age at the end of 2030.

With around 2,800 in the industry, this means the number of guards the industry can reasonably expect to lose over the next five years could fall somewhere between 700 and 1,200.

Even given a more industry-standard retirement age of 62, each of the six selected rail-specific roles would be expected to lose at least one in six employees, with others pushing to or above a quarter.

This age would see 25% of signallers reach retirement age by the end of 2030 (accounting for around 1,300 employees), close to 28% of driver managers (over 200 employees) and 20% of Electrical Control Room operators (ECROs) and testers (approximately 40 and 200 employees respectively).

In terms of roles that could be considered more prone to threat from other sectors, as well as from retirement - given a retirement age of 62, engineers would be a particular risk.

Electrical and civil engineers would be set to lose around 30% and 27% respectively, accounting for around 350 and 210 employees respectively over the next five years.

Some 20% of project and commercial managers would also be set to retire - this is close to 1,000 project managers and more than 300 commercial managers.

Ultimately, all of this risk would be supplemented by the threat of other sectors hiring these employees away from rail, potentially increasing the volume of employees leaving the industry in the next five years.

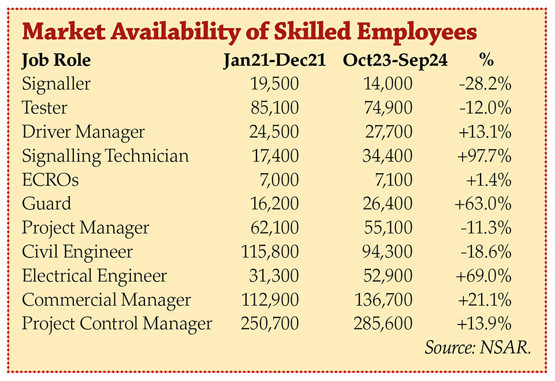

Consideration must also be placed upon the volume of employees available across the country. To do so, data from the Annual Population Survey (APS) has been sourced.

Each role identified above has been assigned to a relevant Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) code, with the volume of employees in each code for the earliest available period (January 2021-December 2021) compared with the most recent available period (October 2023-September 2024).

This should provide a gauge as to how the number of people performing these roles has changed, and therefore the propensity of the industry to be able to replace those we are losing over the upcoming five years.

It should be noted that the data is reflective of the SOC Code most similar to the roles identified - there are (as of most recent data), 55,100 “Engineering project managers and project engineers”, but not necessarily that many in the industry.

The data shows a highly varied picture. The code associated with signalling technicians (‘Electrical and electronic trades’) has close to doubled its volume of employees over the period of data collection, with also large uplifts for guards (‘Train conductors and guards’) and electrical engineers, which has a code bearing the same name.

On the other hand, roles the industry may be less well-placed to replace could include signallers (‘Rail transport operatives’) and civil engineers, which has a code bearing the same name.

CASE STUDY: SIEMENS

“I don’t believe there are any areas of the rail industry supply chain that are not currently suffering from under-utilisation,” warns Rob Morris, Siemens Mobility's joint chief executive for UK and Ireland.

“That’s not good for the government, the taxpayer or business.

“There is clearly a longer lull in work materialising, with little foreseeable upturn. Which means businesses have to cut costs and staff.

“The longer-term concern is that the industry loses capability and system operational knowledge. I’m really keen that you make this point. It is of paramount importance.”

Morris (pictured) has worked in the rail industry for a decade. But he has seen this happen before.

“A lot of my earlier career was spent in the nuclear industry,” he explains.

“We saw it happen after Sizewell B was finished in the 1990s. In the 20-year gap between that and the start of construction of Hinkley Point C, skilled engineers retired and new ones weren’t trained, so the cost to the country of restarting construction was much, much higher.

“Expertise had to be imported and a massive training and recruitment programme started, competing with our industry which was mid-Crossrail construction at that time.

“Short-term spending cuts will just drive up the long-term costs of the railway. Which is exactly the opposite of what the Treasury wants. They will hit economic growth and investment at the same time.

“For example, we have already seen resignalling projects such as York Capacity and Manchester South delayed or mothballed. But both are vital to delivering the benefits of the Transpennine Route Upgrade (TRU).

“Cutting them means you limit the benefits of the government’s investment in TRU. Which, in turn, constrains the growth of cities such as Manchester and Leeds. All of which has a drag on the UK’s GDP.

“When everyone realises this and tries to re-start the schemes, the skills aren’t going to be there. It will take longer, and cost more, to deliver them.”

Morris says that he could see the looming workforce retirement problem as far back as 2018, realising that by 2024 more than half his workforce would be over the age of 50 and therefore potentially taking early retirement. At the same time, Siemens’ signalling work was shifting from conventional signalling towards digital.

He oversaw a programme of investment in what he calls entry-level talent among apprentices and graduates, to build a more resilient and more sustainable employee demographic.

Today, nearly 8% of the workforce is in that group. That, says Morris, underpins the company’s long-term confidence in rail, along with investment in new facilities at Chippenham and Goole.

“There’s got to be light at the end of the tunnel we are currently going through,” he says.

“We do, of course, all get the fiscal pressures the government is under. The answer lies in spending what money there is wisely, by focusing on investments that reduce operating costs, increase revenues, and get more out of existing infrastructure.

“That’s why we’ve focused on digital tech and how battery bi-mode trains and discontinuous electrification can save the industry £3.5 billion, as well as making diesel trains history.”

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.