Current assessments of HS2 are too gloomy, as several frugal tweaks are available to improve its business case in the changed rail market.

HS2 Ltd and the Department for Transport need to acknowledge potential phased outcome scenarios, now that they have scaled back their original aspirations for 18 trains per hour (tph) at Euston. Defining the likely outcomes would help rebuild confidence in HS2’s efforts and prospects.

Current assessments of HS2 are too gloomy, as several frugal tweaks are available to improve its business case in the changed rail market.

HS2 Ltd and the Department for Transport need to acknowledge potential phased outcome scenarios, now that they have scaled back their original aspirations for 18 trains per hour (tph) at Euston. Defining the likely outcomes would help rebuild confidence in HS2’s efforts and prospects.

HS2 could still be as significant as the first motorways. But with depressed rail farebox revenue since COVID, and several under-resourced operators, the previous full HS2 is a much too risky step.

With hindsight, HS2 ought to have started as a Manchester to Warrington quick scheme with reversing platforms at HS2’s Manchester Piccadilly station, and with a better understanding of how best to serve Heathrow and Birmingham’s Curzon Street and Interchange stations.

As a transport economist planner who commuted on the Midland Main Line (MML) for 12 years, I assume that speed north of Handsacre Junction and Crewe is less important than capacity, and that capacity problems near Crewe will be solved. This article therefore discusses reduced and phased variants of HS2’s 18tph design and the likely consequences of smaller HS2 stations at Euston and Crewe, designed to minimise risk and limit operating costs.

Potential adjustments have also been considered in case rail ridership is much more or less than expected, or reliable capacity is more limited than predicted.

Key opportunities

When HS2 costs escalated and its East Coast Main Line relief plans were dropped in the Integrated Rail Plan (IRP), some tentative ideas were floated in the IRP about how to develop a Nottingham-focused variant. Part of the motivation was how to preserve the major time savings to Heathrow and points west that were originally offered from the ECML by HS2.

Those Heathrow benefits to/from ECML stations exceeded central London savings by 40 minutes and are still achievable.

Hourly extended HS2 services to/from the ECML, with connecting services in between, is enough to attract a range of Heathrow (etc) passengers - many with luggage. But to be cost-effective, they need to be part of the CrossCountry/TransPennine Express timetables to Teesside, Edinburgh, and so on from Birmingham or Manchester (or both).

Other opportunities to generate extra revenue arise now that a scaled-back HS2 has spare train paths. For example, some of HS2’s planned double-length trains could be split, making half of them quicker at prime times. Such a strategy can cost-effectively increase frequencies to Lancashire and reduce journey times to Birmingham Curzon Street by up to ten minutes compared with HS2’s plan.

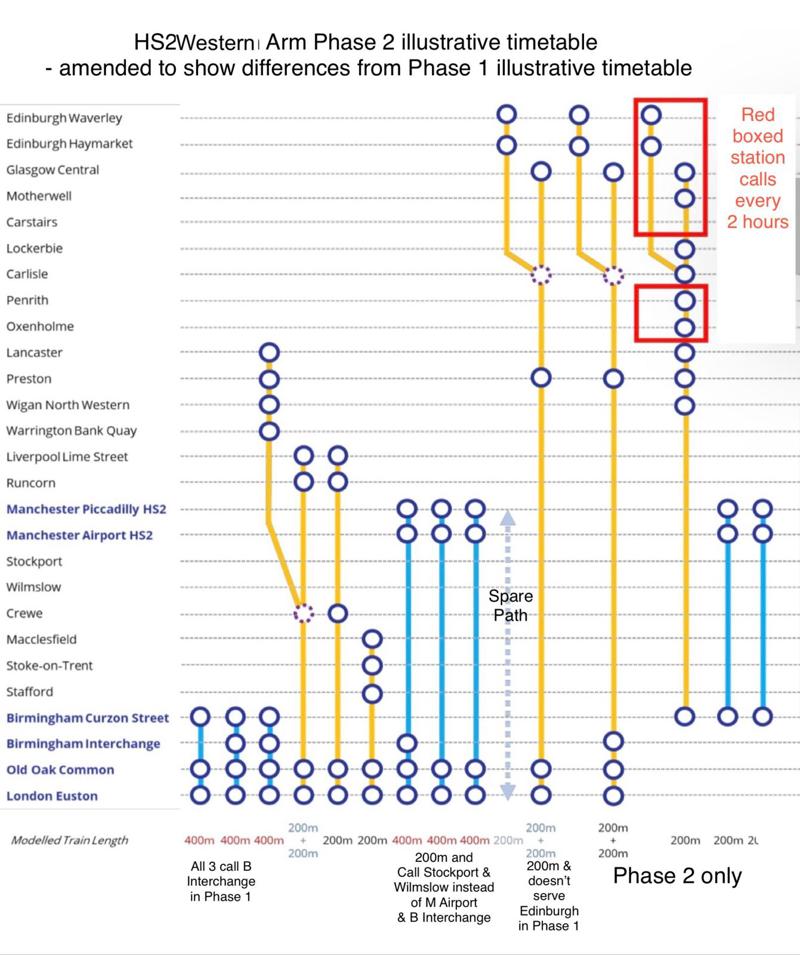

HS2’s planning (shown below) identified the western arm opportunities on which they planned to concentrate. It has been criticised because of low frequencies to key destinations such as Liverpool, Wigan, Warrington, Crewe, Macclesfield, Stoke-on-Trent and Stafford, where HS2 proposed only 30- and 60-minute frequencies.

HS2’s plan also implies uneven arrival or departure patterns at Birmingham and Manchester, although the spare path shown on HS2’s ‘illustrative timetable’ was seen by many as a hidden Manchester, Birmingham Interchange and Old Oak Common or Heathrow service aspiration.

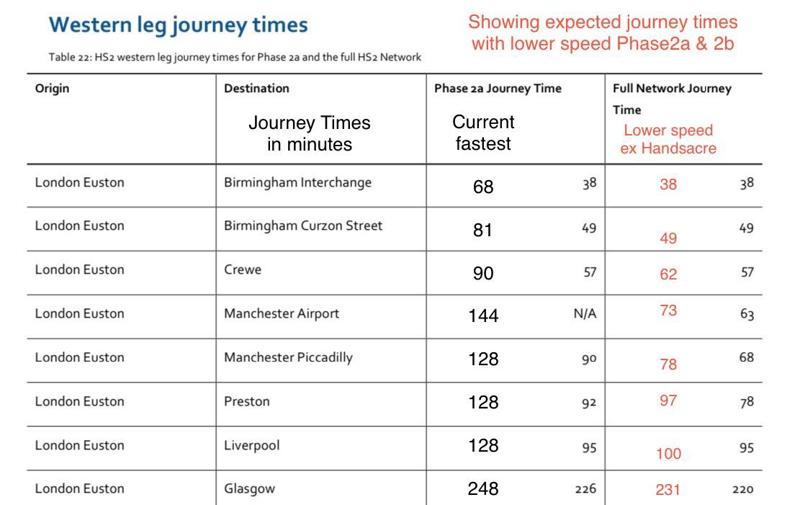

HS2 Phase 1 plans to reduce Euston to Birmingham journey times by 32 minutes. The proposed private sector-funded lower-speed Staffordshire and Cheshire links imply an ultimate 40- or 50-minute reduction to Manchester Piccadilly, but only 28 minutes to Liverpool and 17 minutes to Glasgow, according to my estimates. That’s why the extra services to both the latter destinations are proposed above.

Most frequency improvements generate more benefits than a five-minute journey time saving for full fare passengers, which in this case also smooths departure gaps at Birmingham and Manchester.

As journeys to Heathrow and points west save around 45 minutes on top of those savings, any HS2 extensions north of Birmingham and Manchester are particularly attractive for Heathrow journeys (for example) to and from Leeds and beyond. This should reduce the need for internal flights.

Old Oak alternatives

Alongside (or instead of) the above juggles, some relief services could start or end at Old Oak Common and maintain eight-coach operation for longer. Doing that would increase Birmingham Interchange’s connectivity and lessen the threat of overloaded services at Old Oak, which 25% of HS2 forecast passengers prefer as their interchange rather than Euston. Any such pairings could be seamlessly recombined at quieter times of day, or during some driver shortages.

The ideal Old Oak arrangement would be to reserve one central platform at Old Oak as a spare to hold empty or disabled coaching stock, and the other for Birmingham services turning there.

That seems to restrict the latter to one Birmingham train per hour arriving at Old Oak at xx45 or xx51 and departing at xx10, plus one at xx11 departing at xx30 or xx34 to use the empty spare paths ex-Euston.

The remaining empty arrival slots seem to be an xx25 arrival slot at Old Oak and empty departure slots at Old Oak of xx30 or xx34, subject to the expected seven minutes running between Euston and Old Oak.

Alternative illustrative timetables could change those spare slot distributions or require passive provision for Old Oak sidings. Potential passive provision for such sidings needs limited tunnel throat widening and the retention of the Atlas Road service tunnel.

Any subsequent widening in the 2060s could be carried out in a way similar to that used to build extra cross-passages or the Battersea extension of the Northern Line.

If sidings are justified, extending them to Camden Road and HS1 stations in the 2070s could also be considered.

Beyond Birmingham

Either arrangement with the Old Oak extras would eventually have enough passenger capacity to allow four or more services each hour to be extended to Derby and beyond from Curzon Street.

That would require battery-equipped rolling stock or infill electrification, and connections to be built.

It could offer ten-minute faster services to Derby and Sheffield, more frequently than the Midlands Main Line’s aspirations by 2050, and relieve the line’s limited capacity at four-platform St Pancras.

The necessary rolling stock orders could be provisional and timed to optimise that relief in the light of MML and HS2 experience.

The MML was to be relieved by the eastern arm of HS2 - and still could be in that frugal way around 2050.

Nottingham could benefit by eight-minute journey time savings from St Pancras at the same time - if the fastest MML Sheffield services are diverted to Nottingham and the eight-minute slower semi-fast services are sent to Sheffield and Derby.

That would improve MML connectivity from Luton (etc) and Nottingham’s services, and avoid overstretching St Pancras’s limited four MML platforms.

Ultimately, that requires HS2 branded trains to be squeezed onto the existing network south of Derby by using the paths of two pairs of CrossCountry services.

The Nottingham and Derby to Cardiff Turbostar services could be diverted via Leicester and Loughborough (a route upgrade already funded by previous announcements), perhaps with half serving Derby and half Nottingham.

CrossCountry’s Bristol and beyond services could turn around at Birmingham International (connected by the committed driverless shuttle to the Airport and Interchange Station) or Northampton.

North of Chesterfield, some (battery or diesel) regional services might need to be diverted via the Barrow Hill Goods Line and approach Sheffield from the north, to optimise capacity north of Dore.

Regional services currently start in Nottingham and head to Leeds, Manchester and Liverpool via Sheffield (hourly on both routes), and could justifiably stop at key new stations en route.

The MML’s semi-fast Sheffield (about to be bi-mode) service could, if needed, follow the Barrow Hill route and head to Manchester to relieve MML congestion around Dore and improve connectivity.

To optimise those benefits, passive provision should be made to replace and enhance Derby’s CrossCountry services. As Derby will be the home of Great British Railways, that modest cost eventuality is well worth preserving.

Conclusion

This article assumes that the efforts of others to resolve WCML capacity issues will be successful. It discusses opportunities and problems, and the space they create for complementary proposals.

HS2 could plan to provide extra journeys to Glasgow, Manchester, Chester (post-electrification) or Liverpool, to improve the business case and connectivity. Doing that with HS2 journeys ex- London reversing at Curzon Street (and in the 2050s complementary proposals for the MML, including Derby and Sheffield) would be the ultimate ideal.

Regular reversing was seen by HS2 as the best way forward for Northern Powerhouse Rail services at Manchester Piccadilly, but unnecessarily complicated by others. Similar reversing at Curzon Street can provide prime station passenger loading time there, and lead to frequency improvements and competitive advance fares to Lancashire, Derbyshire, Yorkshire and beyond.

HS2 Phase 1 plans to reduce Euston to Birmingham journey times by 32 minutes, and the mayoral announcements imply a 40-/50-minute reduction to Manchester Piccadilly.

Journeys to Heathrow save around 45 minutes on top of those savings, making any HS2 extensions north of Manchester particularly attractive for Heathrow journeys to and from Leeds and beyond, reducing the need for domestic flights.

Passive provision designed with all the leading options in mind is inexpensive now - and doesn’t imply that all will actually be needed.

It mainly involves building HS2’s already planned high-capacity Euston approach throat - plus minor preparatory widening of Old Oak tunnel throats.

It could also include preliminary scoping to evaluate if follow-on rolling stock orders should include tilting or battery power mechanisms, now that the highest speeds only apply to HS2 Phase 1.

Plans need to be re-examined looking for economic case improvement opportunities to justify using the HS2 ‘black hole’ funds and to release the money Manchester Airport had offered to put in. The ideas in this article share that aim. HS2’s ‘illustrative timetable’ needs to be independently re-examined as a baseline (or variant) business case.

Stuart Porter is a retired DfT planner.

For a full version of this article with more images and data, Subscribe today and never miss an issue of RAIL. With a Print + Digital subscription, you’ll get each issue delivered to your door for FREE (UK only). Plus, enjoy an exclusive monthly e-newsletter from the Editor, rewards, discounts and prizes, AND full access to the latest and previous issues via the app.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.