Move over High Speed 2 Phase 2a… the ‘Staffordshire Connector’ is coming.

That’s the gist of a report produced at the prompting of two powerful metro mayors representing Greater Manchester and the West Midlands. While Andy Burnham is still in place in Manchester, elections earlier this year toppled his former partner Andy Street in favour of Labour’s Richard Parker.

Move over High Speed 2 Phase 2a… the ‘Staffordshire Connector’ is coming.

That’s the gist of a report produced at the prompting of two powerful metro mayors representing Greater Manchester and the West Midlands. While Andy Burnham is still in place in Manchester, elections earlier this year toppled his former partner Andy Street in favour of Labour’s Richard Parker.

But that didn’t stop the work which Conservative mayor Street had championed hard after then-Prime Minister Rishi Sunak cancelled HS2 entirely north of Birmingham (RAIL 994). And while Burnham and Street both stressed last February that they were not looking to reverse Sunak’s decision and reinstate HS2 - “This is not HS2 by the back door,” said Burnham back then (RAIL 1003) - the Staffordshire Connector will follow the same route if the Department for Transport accepts the mayors’ new proposal.

The line would be fit for 186mph (300kph) running, rather than the 225mph that HS2 proposed. It would have ballasted rather than concrete slab track, which the latest report estimates could save 30% in capital costs. It would have a British loading gauge, rather than the larger European one. And it would have simpler interfaces to Network Rail’s infrastructure, particularly around Crewe. This makes it closer to the French concept of high-speed lines, which lay ballasted track onto a foundation that is topped with asphalt, making a new line initially resemble a road.

Such a design could be easier to price and make delivery more certain, because contractors can bring their existing experience to the work.

However, there is a trade-off between lower capital costs to build the line and subsequent higher maintenance costs that come with ballasted track. HS2 had concluded that slab track gave lower whole-life costs and that the higher speeds it permitted gave more benefits in terms of faster journeys.

This is the compromise on which ministers must decide. The Staffordshire Connector may come with cheaper up-front costs, but it then brings lower benefits according to Treasury economic models, and higher maintenance charges. Using the more familiar French concept might make finding private finance for the route easier if ministers remain unwilling to commit public funds. However, the report acknowledges concerns around private investment even as it lists advantages in affordability, cost controls and risk management. It admits that private funding models have fallen from policy favour amid “concerns about long-term value for money, given that these deals are often more costly to the public sector in the long-run; and the difficulty in both sides understanding, forecasting and pricing risk effectively, which could lead to either the public sector getting a ‘bad deal’, or the private sector partner taking on too much risk and ultimately collapsing”.

However, it also sees advantages. The new line is largely segregated from existing tracks, which makes it easier to build. It sits on a corridor with strong transport demand, which should provide confidence of long-term repayment of initial investment. It is also relatively straightforward to deliver, although the report admits to serious complexities at Crewe where it links into Network Rail’s West Coast Main Line.

For the Staffordshire Connector, government already holds construction powers from an Act of Parliament and has secured significant portions of the land needed. This means that construction could start relatively quickly and separately from development work on the second part of the new line. The report calls this second part the ‘Cheshire Connector’, which would run from Crewe to Manchester and link with Northern Powerhouse Rail. The previous HS2 plan called this Phase 2b, which included a station at Manchester Airport and a long, tunnelled approach into a new station alongside Manchester Piccadilly that would be fit for HS2’s 400-metre trains and have capacity for NPR, too.

This second stage does not have approval. MPs were part way through considering a parliamentary bill when Sunak pulled the plug. The mayors’ report almost suggests this is an advantage, because when the time does come to seek legal consent to build the Cheshire Connector it can be done in conjunction with Northern Powerhouse Rail, to bring forward an integrated design and build programme for both projects. It also leaves to a later day the inevitable discussion between the merits of HS2’s planned terminal at Piccadilly and Mayor Burnham’s wish to see a through-running station placed underground, which would be more expensive to build although easier to operate.

For now, however, how to fund the new lines is another decision for ministers. It represents another compromise, this time between the taxpayer funding construction upfront or handing the project over to private finance. The former gives higher short-term bills, while the latter likely presents an overall higher bill but with lower annual payments. The mayors’ report comes from a team headed by Sir David Higgins, who has had a distinguished career in construction, has headed Network Rail, and chaired HS2 Ltd. His team included Arup, Addleshaw Goddard, Arcadis, Dragados, EY, Mace and Skanska.

In his foreword to the report, he says: “We strongly recommend that the newly elected government preserve the existing powers and land safeguarding, and spend the next six months working in partnership with the Metro mayors and the private sector to develop a detailed strategy for delivering critical change.”

The report itself lays out a case for change, which could be applied more widely than simply to building 50 miles of new high-speed railway from Fradley Junction (where Phase 1 should end) to High Legh (where NPR assumes responsibility for the tunnelled miles into central Manchester).

It says: “The UK stands at an inflection point. We have incredible social and economic assets - vibrant cities, leading global universities, world-class air and seaports, and a thriving life sciences sector. But having been mired in persistently low growth and low productivity for over a decade, our economy is underperforming many of our peers.

“We are also one of the most spatially unequal societies in Europe, with a significant gap in economic output and living standards between the South East and the Midlands, the North West, and other regions.”

It continues: “The question is not whether we need to do this, but how we can best achieve it. On this, the evidence both from across the globe and here in the UK is unambiguous: high-quality, affordable infrastructure is the best recipe for stimulating economic activity, and transport is the key ingredient - spanning the movement of both people and goods.”

The previous government had already rejected building major new motorways, arguing in 2022 that high-speed rail was preferable “in terms of increasing capacity, connectivity and sustainability of inter-city travel”, in a report that examined alternatives to taking HS2 into Manchester. This same report noted that building a conventional railway would bring costs “almost as high” as high-speed rail, but without delivering reduced journey times while bringing “only marginally fewer environmental impacts”.

A 2016 report from Atkins also looked at alternatives, but found for Manchester: “No conventional alternative option was identified that could connect Manchester to HS2 that was not unreasonably disruptive.”

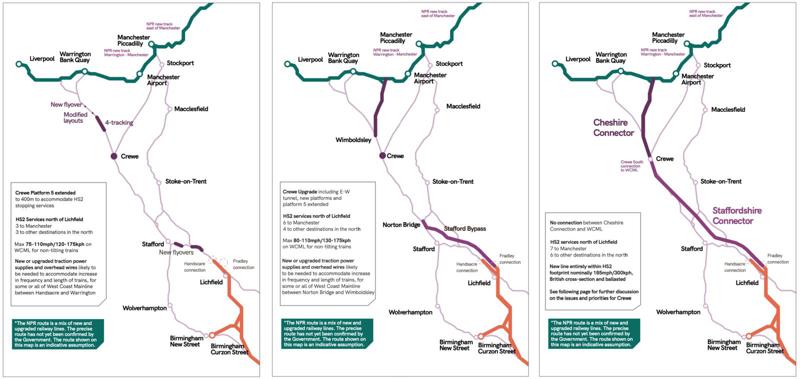

Nevertheless, the mayors’ report felt it necessary to look once again at alternatives. It drew up three concepts. Concept A looked at upgrading the West Coast Main Line with new flyovers either side of Colwich Junction, four-tracking between Winsford and Hartford, and a 400-metre Platform 5 at Crewe. Concept B included a new line from Fradley Junction to Norton Bridge to provide a bypass around Stafford, the Concept A extension to Crewe Platform 5 as well as new platforms elsewhere in the station, and a new line from Wimboldsley (just south of Winsford) northwards to meet the proposed NPR route.

Concept C brings the two connectors - Staffordshire south of Crewe and Cheshire north of Crewe. It forms the report’s preferred option and delivers (in its opinion) 75%-85% of the benefits of the HS2 plan for 60%-75% of the costs, although it is more expensive than Concepts A and B. It describes its Staffordshire Connector not “as an end-state in itself” but as a first step that “would send a powerful message of confidence to the Midlands and North West and the rail industry”. But while this two-stage solution looks clear, there is more work to do around Crewe, as the report admits.

It says: “Any solution to increase north-south capacity through Crewe will be expensive and disruptive and requires more detailed development work with Network Rail and local stakeholders to resolve the deep-seated challenges in this part of the railway. Our approach leaves open several options, including a dedicated north-south bypass for through trains.”

It now calls for work between government, Combined Authorities and private companies to find the best way forward over the next six months. More immediately, it wants ministers to reinstate safeguarding measures over land needed but not yet bought for what had been Phase 2, and keep in state ownership land already bought for Phase 2a. Both measures would reverse commitments made by the previous government. That all gives ministers time to consider the compromises the report puts forward and decide whether they wish to continue Britain’s recent history of being a country that invests less in infrastructure than its peers.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.