Why should rail employers take on people from disadvantaged backgrounds? As well as the right thing, Paul Clifton learns that it’s essential for the future.“I was an agency worker on a zero hours contract,” says Ajmal Nazir.

Why should rail employers take on people from disadvantaged backgrounds? As well as the right thing, Paul Clifton learns that it’s essential for the future.“I was an agency worker on a zero hours contract,” says Ajmal Nazir.

In this article:

- The rail industry needs to recruit from disadvantaged backgrounds to sustain its workforce as wella as to bring in diversity.

- Replacing 10-20% of retiring workers with disadvantaged people could generate billions in social value and reduce unemployment.

- Training programs like QTS Rail Skills Academy provide disadvantaged individuals with skills for long-term rail careers, benefiting employers.

“I was an agency worker on a zero hours contract,” says Ajmal Nazir. “I could not rely on it, and I did not have a trade like a carpenter or builder.

“I got a call from the careers service to attend a document control programme at college. There was a four-week course and then two weeks of pre-work trial, which was paid. At the end I was offered a position at Balfour Beatty Vinci. That’s how I got into construction in the rail industry.”

Nazir is one of 4,500 people who have found roles on HS2, despite initially not having suitable qualifications. A requirement to recruit from diverse backgrounds is embedded in every supply chain contract.

“After one year I was promoted, and I am going on a course to get more qualifications,” he says.

“Now my daughter has just finished school after A-levels. She is on work experience at BBV, and she is applying for an apprenticeship. That is another benefit in my home.”

Natalie Penrose is director of stakeholders, skills and inclusion at HS2.

“The industry has an ageing workforce,” she explains.

“The majority are white, male, and over 45. We need new blood. We need to fish in different pools to find people who think and work differently to what has gone before.”

HS2 employment peaks this year, with 31,000 people working on the construction.

“To sustain that massive number, we need to keep bringing new people in,” says Penrose.

“We require our supply chain to find people who are currently unemployed, skilling them up with pre-employment training, and keeping them in employment for at least 26 weeks.

“The aim is to benefit them for the rest of their lives. We are trying to change the industry to be a place where everyone can have a career, regardless of background.”

“The Treasury doesn’t care about social value,” says Neil Robertson, chief executive at NSAR (National Skills Academy for Rail).

“But it does care about the economic value of getting people off benefits, off the dole.

“Future rail investment will depend on the quality of the job creation, more than the speed or comfort of the train.

“Instead of using the money to recruit and train young people, especially from disadvantaged backgrounds, we’re paying expensive consultants and agencies and poaching from each other. Which leads to wage inflation. That decreases our productivity by increasing unit costs.

“We change that by recruiting and training. The balance has to shift.

“We haven’t measured it properly before. Now we can. We are doing good stuff - but we are doing it in pockets, and we are not doing it systematically. We have to pull that together into a strategy.”

New analysis

NSAR has carried out new data analysis for RailReview. It calculates that by 2030, the rail sector will need to replace 70,000 of its current employees, due to retirement and other reasons for leaving the workforce.

It has modelled the social value that would come from filling a proportion of those roles with people from a disadvantaged background. It worked on a figure of one in ten, but suggests that the proportion could stretch as high as one in five.

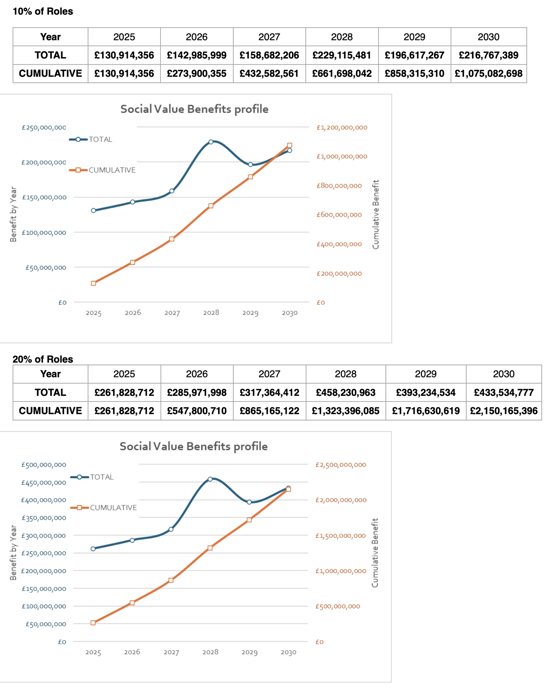

“Replacing 10% of those leaving the industry to 2030 with people from a disadvantaged background would create over £1 billion of social value, including a peak of £230 million in 2028,” says data analyst Sam Goody.

“Increasing this to 20% would swell the total figure to £2.bn of social value and the peak to £450m in 2028.”

What exactly constitutes NSAR’s social value, and how does it translate into money?

“It includes securing a job, enrolment on a training scheme, commencing and completing an apprenticeship, and other employment training. It also accounts for improvements to local health and environment, increased financial inclusion, lower levels of youth anti-social behaviour, increased social groups, higher levels of physical activity, and reduction in homelessness.”

NSAR carried out detailed modelling for the Northumberland Line reopening and for the Transpennine Route Upgrade (TRU).

With above-average unemployment in the North East at 6% and a catchment with significant deprivation, NSAR argues that the social value added was a significant factor in securing public funding for Ashington-Blyth.

For TRU, it found that the peak workforce shortage would reach 15,000 people in 2026, made worse by other rail investment absorbing existing skilled workers in the North West and Yorkshire regions.

Half the posts would have to be filled by people either not in the rail industry or not from the surrounding areas. That would bring an economic value of £1.2bn. But that figure could rise by a third, should a proportion of those jobs be filled by local people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“The Conservatives were stumbling towards a new test, and didn’t quite get there,” says Neil Robertson.

“Labour should get there. The test is how many good jobs you create for each pound invested.

“Investment in the railway is not about trains. It’s about job creation, it’s about growth, it’s about tackling poverty. It’s what the military do - make good people out of unpromising material. The railway can do that.

“We need a bridge to get people in. Pre-employment programmes can get disadvantaged people to the point where they are ready to be recruited.

“It’s also about employers shopping local for staff. That’s right for so many reasons. You’ve seen Sir Keir Starmer talking about the solution not being keen, eager people from overseas. We have to reach deeper into our communities, and it will be noticed when we do it.”

At HS2, Natalie Penrose backs up that comment.

“There is a constant drum beat to this - both back-office and frontline work. This doesn’t just happen by accident. - when a company bids for work on HS2, it has to demonstrate it. We build it into contracts and monitor it every three months. We make sure they are bringing in apprenticeships, doing work placements, going into schools.

“That’s the lesson from this: not just meeting the numbers, but also making sure they are good-quality jobs. You have to embed it in the contracts and in the culture.

“We require suppliers to deliver 4% of the workforce as apprenticeships. That’s 2,000 over the life of the project, and we are at 1,600 now. We don’t have a target for getting people out of unemployment. But we’ve had 4,500 so far.

“The aim is to benefit communities close to the line of the route. For obvious reasons, there is heavy concentration of recruitment in Birmingham and London.

“We’re making sure local people don’t just see the misery of construction and noise and road closures. They won’t get on the railway until the early 2030s, but they can see some more immediate benefits now in their area when people get jobs.”

Neil Robertson adds: “Only a certain number in a cohort can be disadvantaged, otherwise it becomes too difficult. You can only have a certain number of apprentices in the workforce, otherwise it becomes a college

“Railways can require quite highly skilled recruits. As they become more complex, that means there is a bigger bridge to cross. Rail is getting better at this, but we are not quite making the argument yet that we are the right investment for government.”

Recruiting at ground level

“The experience has been life-changing,” says Joseph Little.

“It’s opened a door for me into a new career path. Without it, I probably wouldn’t have been able to pass through these first steps.”

Little attended a basic training course at the QTS Rail Skills Academy in Scotland from February to April this year. Now he has a job as a trackman operative at D J Civil Engineering.

“It has given me a new lease of life when I needed it the most,” he says.

The company reports that he has now been trained to work on several track machines and is about to swap his blue hat for a white one, “which demonstrates just how quickly he is developing in a rail environment”.

Kirstie Stevens did the course last autumn and is now a track operative at Story Contracting.

“I got so much support and everyone was keen for us to do well,” she says.

“I can’t believe I got offered a job on the last day. I’m still shocked, but this has been the best thing I’ve ever done.”

The company took two people from the same cohort and states: “This is the blueprint for future operative recruitment.”

“They don’t look diverse. They tend to be young white males,” points out QTS Training Managing Director Lorna Gibson.

“We have people who are neuro-diverse. They may have experienced life in care, or be third-generation unemployed, or we’ve had ones living in supported accommodation. Some have not held down a job. Most have not had a great experience with education.”

But 97% of the young people who’ve been through her ten-week training course have successful outcomes. That’s a high number for any form of training.

Gibson adds: “The rail industry has a critical skills shortage. People just don’t know the opportunities are there. And our young people have come across a lot of barriers.

“Getting into the railway is hard for them. You require a sponsor. To get a sponsor, you need competencies. To get competencies, you need a sponsor. A lot of these people don’t have the confidence to get round that.”

Ten or 12 people at a time join the courses. In two years, more than 80 have been through the QTS Rail Skills Academy. The number will top 100 by the end of the year.

The first week includes passing the drug and alcohol test required by Network Rail. For some, says Gibson, that can be a big stumbling block.

They then move on to health and safety, emergency first aid and mental health awareness, manual handling and fire safety. Soon they’re on personal track safety, working on small tools, and later specific equipment used by contractors likely to hire them.

For some, the six weeks in a classroom may be the longest they’ve ever sat at a desk. The written assessments may be the only tests they have ever passed.

But they emerge into four weeks of on-site training with accredited skills on their CVs, doing real work and gaining abilities an employer would value.

What’s in it for the local authorities who are paying for this? So far East Ayrshire, South Ayrshire, South Lanarkshire and Fyfe have put up the money.

“It saves the councils large amounts of money,” Gibson explains.

“These young people cost a lot. They’re getting universal credit and housing benefit. They’re supported by keyworkers. They’re going from benefit receivers to taxpayers.”

And what’s in it for a potential employer?

“The railway has an increasing proportion of over-50s, and a decreasing number of under-30s. Employers struggle to get employees, and we’re finding them.

“These are people who’ve been tried and tested for ten weeks. They’ve kind of done a ten-week job interview. They have a list of competencies that would cost an employer a lot of time and money to put them through, so they get quite good roles.

“And they’re very loyal, because of the route they’ve come through.”

QTS, which employs 700 rail workers, has taken on 15 of the trainees. Others have found work at different rail contractors. At the end of each course, senior staff from potential employers sit down with each person in turn.

“They move into a variety of roles - civils, drainage, fencing, vegetation,” says Gibson.

“They might go on to do NVQs or an apprenticeship. Some have gone up to safety-critical training. One lad is now going to college on day-release to study civil engineering. There’s no real limit to their opportunity.

She’s talking about Murray McAllister, who finished the course last November and went straight into a job as a civils operative at Track Civil Engineering Solutions.

“The programme is really good, particularly the work experience that lets you see what a career in the rail industry is really like,” he says.

“It has given me the opportunity to make a career I never really thought of before.”

His employer describes McAllister as “one of our most promising apprentices with a strong desire to learn”.

“I could say we’re doing this because we’re nice people and we want to do the right thing,” concludes Gibson.

“But really, we’re doing this because we need to bring young people from different backgrounds into the industry. We can’t just wait for the right people with the right skills to walk through the door, because they’re clearly not doing that.

“But changing lives at the same time is just amazing.”

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.