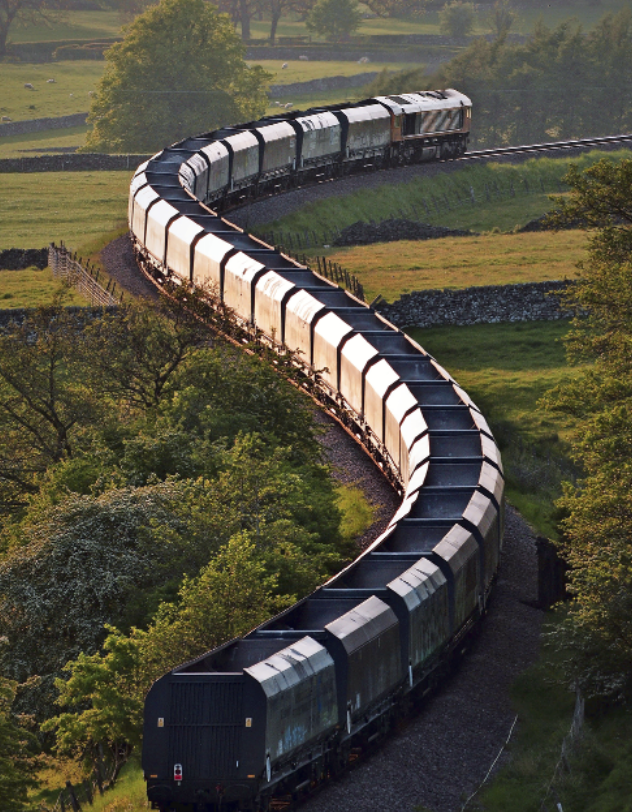

Removing diesel-only trains from the network by 2040. Yes, even freight trains. With net zero greenhouse gas emissions achieved by 2050. These are headline acts in the Transport Decarbonisation Plan.

They seem a long way in the future, especially with the sale of new purely petrol and diesel cars banned less than nine years from now.

“Electrification is the big-ticket item. Good benefits and early realisation from mature technologies,” says Rod Anderson, Rail Research Co-ordinator at the University of Southampton.

“That’s a relief. Hydrogen and batteries get all the press, and they have their place, but the grown-ups seem to be focused on electrification.”

But he warns: “Don’t emit limitless carbon in order to reduce traction carbon. There is no point busting your entire carbon budget building the infrastructure if you then need decades of traction savings to recover it. Carbon is a bit like compound interest: if you burn it early, the costs are harder to claw back.”

David Clarke, Technical Director at the Railway Industry Association, adds: “Our mantra is to get a rolling programme of electrification started now. Something like 300 miles of overhead line equipment would get 80% of freight under the wire. That is the obvious quick win.”

The Transport Decarbonisation Plan is a 220-page blueprint covering all transport modes. According to Secretary of State for Transport Grant Shapps, it is “the first in the world”. The nine supporting documents include a rail environment policy statement.

Shapps also said: “It is not about stopping people doing things, it’s about doing the same things differently. We will still fly on holiday.”

Despite what Shapps said, most commentators agree that meeting the targets will involve travelling less - especially by air and road. Politically, decarbonising is a hard sell: transport is the largest contributor to UK greenhouse gas emissions. But for the emerging Great British Railways, this is a significant opportunity.

Rail Delivery Group Director General Andy Bagnall says: “The Government should use a polluter-pays approach when considering taxation, such as air passenger duty.”

The big news for freight in the decarbonisation strategy was that the ban on new petrol and diesel cars is being extended to all heavy goods vehicles by 2040.

Because no alternative zero-emission propulsion for large lorries currently exists, there is a commitment to increase the modal share of rail freight, which is also diesel-hauled, but for which the alternative of low-carbon power already exists.

But the reports and strategies collectively avoid the elephants in the room. A £27 billion roads programme continues. But apart from the already-started HS2 and East West Rail, large-scale rail enhancements do not.

And while fuel duty for cars has remained the same for a decade, public transport fares have increased significantly. What will the Government do as fuel duty revenues plunge and electric vehicles take over? Will there be distance-based road user charging?

Clearly the road to zero-emission transport contains many uncertainties.

Quick wins: the low-hanging fruit

“The starting point is to do things, rather than talk about them,” says Professor Simon Blainey at the University of Southampton’s Transportation Research Group.

“We have been talking about network-wide electrification for 20 years. Just do it. It will deliver decarbonisation effectively. Battery and hydrogen may be useful as back-up, but they aren’t as efficient as overhead electrification, or even third rail.”

RIA’s David Clarke says the starting point is to electrify the main diesel lines, beginning with the rest of the Midland Main Line and over the Pennines. East West Rail should be electrified from the start, he says.

“And Great Western - it would be easy to complete the job that was stopped partway through. The prep has all been done. All the work through Bath - the bridges are cleared and the power is in place.”

Clarke adds: “There is such a lot to be done around reducing our energy consumption. Not all stations have LED lighting. Stations should be exemplars of sustainability in terms of energy use and waste-water recycling.

“There needs to be a change in mentality. There is no value put on carbon saving in tenders. If there was, say, a 5% premium on doing a job the low-carbon way, a bidder wouldn’t put that in, because 5% could be enough to lose the bid. Network Rail now expects all designs to be run through a carbon tool to give it a value, but I am not sure it is reaping what it should.”

Rob Morris, Managing Director of Rail Infrastructure at Siemens Mobility, says the Government needs to mandate green technology in all purchasing processes.

“If you want change ‘now’, then ‘now’ actually means a purchasing process has to start. Somehow, we have to unlock the fuzziness around competition. Everything is cost-based, as opposed to value-based. The technology to change things is available now - we just need to leverage it.

“If you unlock the opportunity to bring in third-party investment, it will be quicker because there will be no up-front public capital expenditure at a time when the public economy is stretched and struggling. Third-party spending will bring forward the operational and carbon savings.

“There is loads to go at, but on current plans I can’t see the railway being decarbonised until 2060. Or beyond. It just won’t happen unless we bring that investment forward.

“We are doing it in pockets. Outcome-based specifications create the environment. In Scotland, in our signalling partnership, Siemens Mobility is working in harmony with Scotland’s Railway, with early contractor involvement. We are developing new ideas in partnership, looking at each route as a whole rail system and recommending the best technologies for each section, such as battery or hydrogen as interim or permanent solutions, depending on the feasibility of electrification.

“On the East Coast power supply upgrade, we are working with Network Rail to come up with the most energy-efficient solution. In-cab signalling makes the railway more reliable, but it also has less installed carbon because there is less infrastructure - no lights on sticks, less concrete, more cloud-based technology.

“These are system components. What we need is a mandate from Government, explicit about the way things are purchased for the whole system, at pace, if the targets are to be met.”

Blainey says: “We need to understand the embedded carbon in the infrastructure. For a lot of standard procedures in rail, there is no knowledge of how much carbon is produced. We need to understand where it is generated and where the problem areas can be found. From there, we can find the quick wins.”

Anderson agrees: “This is motherhood-and-apple-pie stuff. We need tools to assess carbon benefit against cost ratios, and work fast to produce more effective carbon-accounting tools. I suspect the way we account for carbon isn’t keeping up.

“Happily, these often go together - less material has a strong correlation with reduced cost and quicker construction. And this can be continuous improvement - start building now, but get better as you go.

“Network Rail is planning research into wind loading on overhead line equipment, better pantograph performance, and the actual behaviour of structures. The more you understand, the more reliable and economical the designs will be.

“It may not get the headlines of hydrogen and batteries, but composite masts matter. We have to start eating into our carbon emissions now. The sooner we get our act together on the infrastructure programme, the sooner the fleet can be decarbonised.”

Blainey says: “Rail is still fundamentally a more carbon-efficient mode than others. We just need to make sure that building is about bringing people from other modes, and not just making things better for people who already use rail.

“So, don’t build for yesterday’s market. This is where some capacity enhancement schemes in the South East may no longer be needed. They may not be the most sensible way to spend carbon.”

Network Rail has “lots under way”, says Chief Environment and Sustainability Officer Jo Lewington.

“The five regions that make up Network Rail each have their own environment teams, so when we renew infrastructure, we do it in a way that is sustainable - and that protects against climate change,” she explains.

“We are looking at catastrophe modelling. We need to build a more resilient railway, knowing where our hotspots are. We are early in this journey.

“We have four pillars of strategy: sustainable land use, decarbonisation, climate change adaptation and what we call the circular economy - minimising waste and use of resources.”

Lewington points to a move from traditional station platform components to low-carbon materials. These reduce embedded carbon by up to 90%.

“We are halfway through Control Period 6. At the beginning of this financial period, the environmental sustainability strategy wasn’t on the radar. This has come along partway through a funding period, and therefore it has been challenging. We know what we need to do, but we are not truly funded to do this.

“Some of it is not about spending more money, it’s about doing things differently with the money we have.”

Quick wins: Rolling stock

Blainey criticises the lack of a coherent national rolling stock strategy, arguing that carbon is not a factor in most spending decisions.

“Some new trains are more energy efficient, so an investment in embedded carbon will produce savings. But you don’t necessarily want to scrap very energy-efficient third-rail EMUs if they can be repurposed and used for another 20 years, thereby reducing the carbon cost.

“The industry is terrible at this. South Western Railway is the classic case. The old South West Trains ordered new suburban rolling stock. Then a new operator took over the franchise and wanted different new trains. That left a whole fleet of additional EMUs in search of a purpose, as well as pushing aside perfectly good retractioned older trains. I doubt carbon cost was considered in that at all.

“If you have a new train that is 5% more energy efficient, but you spend a lot of carbon building it, it will never pay back that carbon. Keeping an existing train running for an extra 20 years, you only need to build a new train every 50 years instead of every 30 years. That will trump anything up to perhaps a 40% operational carbon saving.

“All that carbon stays in the atmosphere. It isn’t something you can easily trade off in the future against emissions now. The critical thing is to reduce carbon emissions overall. We are not capturing this in the decision-making process, because carbon benefits do not accrue in the same way as economic benefits. You have to value decisions in a different way.”

RIA’s Clarke says: “There are fleets coming to the end of their useful lives. We need to be making decisions about the Class 15x Sprinters. They have perhaps five years left. The ideal choice is to spend the next five years putting up wires, so the Sprinters can be eliminated.

“But they’re often used where the electrification priority is much lower. That’s where we can look at interim solutions such as battery and hybrid. There are players offering re-engineered stock that retains the bodyshell, with its embedded carbon and useful life. We’d like to see a bit of that.

“And people are doing clever things to reduce the carbon in diesels. There’s a hybrid trial on Chiltern. There’s Eminox, reducing emissions with passenger and freight. If we are thinking of whole-life carbon, extending the lifespan while reducing the emissions is a sweet spot. There’s a lot to go at there.”

High-speed Rail vs Air and Road

Professor Blainey puts the argument bluntly: “If the Government does nothing to reduce cheap flying, rail is not going to fulfil its carbon-solving potential. HS2 can be positive, but it has to be used to pretty much get rid of domestic aviation - and airport expansion.

“But it isn’t being economically planned at that level. The Transport Decarbonisation Plan states that everyone should continue to have access to affordable flights. I’m sorry: why? Everyone should continue to have access to affordable long-distance transport. That is not the same thing.

“Within that, rail has to get better at understanding why people make their mode choices. You have to stand in the shoes of someone preparing to make a journey, and weighing time, cost, convenience and perhaps carbon. If rail takes 50% longer, costs 25% more and is a lot more hassle, people will jump in the car - or, worse, get on a plane. Rail is not good at this.

“The reality is that most people have a car on the drive. The cost of an additional journey is relatively low, and people don’t consider the whole-life impact of one journey. Once you put one person in that car, taking the rest of the family is virtually zero cost. That’s not how rail works at all: four people travelling is close to four times the cost. Until you start to address that through fares policy, you are wiping out a lot of potential modal shift.

“However concerned you are about the environment, there comes a point where you can’t afford to take the train in terms of money or time. In Switzerland and Germany, they have affordable annual rail passes that give access anywhere, making an additional journey marginal, like the extra car journey. It’s a switch to whole-life cost. And the passes cost less than my annual season ticket between Oxford and Southampton.

“Do we need to be more radical in our discussions about fares, to deliver a carbon benefit? Tinkering around with flexible season tickets will not achieve that.”

RIA’s Clarke agrees: “Rail accounts for 1.5% of transport emissions. If we didn’t bother, it wouldn’t make a material difference to the big picture. I’m not advocating that. It illustrates that we need to be focused on modal shift. It’s about making rail attractive to people who are not using it. We now have a societal motive for doing that.

“It has to unlock the benefits of investment in infrastructure like HS2. As a rail user, I wouldn’t say it is a simple or understandable system, or that ticketing is transparently fair and reasonable. To a non-rail user, it is opaque.

“If we focus on low-carbon journeys rather than just low-carbon rail, we need to be part of the bigger system. And that means being able to buy a single ticket for an entire journey, over however many modes of transport are involved.

“The large number of people who don’t get on a train from one year to the next need to find it much less complex. We have to convert the car-only travellers. Great British Railways has to be about Great British Transport.”

Blainey says: “Land-use planning is the most fundamental element that needs to be changed to decarbonise transport. We have to move to a more sustainable urban structure.

“A lot of this is Government-led - the rail industry can’t change the planning laws. But it can do a lot as a developer to make best use of its land footprint. In Japan, the railway is doing this. And in Hong Kong, MTR runs the railway at a profit because of its property and not because of the rail fares. I do not understand why we are not doing this here. The railway can build housing, entertainment, perhaps retail on its stations, so that rail is the natural means to get there.

“Southampton Central is the obvious example. It’s smack in the middle of the city, and there are high buildings all around it. Why not use the space above the station? It would bring in money and reduce travel carbon. There are so many wins. This would be my big area to focus on: it ticks both the cost and the carbon boxes, and not many things do that.”

NRs Jo Lewington concludes: “Hand on heart, I think sustainability is very high on the agenda. We have two dedicated programmes, one focused on sustainable land use and one on decarbonisation, with workstreams around what we can tackle now - things like renewables, materials that we use, making sure we adopt low-carbon and look at whole-life carbon in all we do.

“But we are not joined-up enough with other modes. We need to look beyond just the rail industry.

“Decarbonisation we can tackle. There might be some funding challenges, but we know what we have to do to decarbonise. It’s doable - sustainability is within our gift.

“How we set up the railway to be resilient to a changing climate is the bigger challenge. Climate change is far bigger than this industry. We can’t achieve all that without outside help, and that’s the real concern.”

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.