The Manchester-Liverpool route was the world’s first inter-city line, connecting the two cities in 1830. Since then, it has been an integral part of the region’s growth. And as the modern railway looks towards its 200th birthday next year, plans are being developed to ensure that it remains just as vital to the region in the future.

As Labour finally revealed its plans for rail in April, with its publication of Getting Britain Moving: Labour’s Plans to Fix Britain’s Railways, there was an impression of the many details that it will still need to outline, having now gained the keys to No. 10. This will need to include much of Network North, the collection of projects packaged up by Rishi Sunak after his cancellation of HS2 Phase 2a last October.

The Manchester-Liverpool route was the world’s first inter-city line, connecting the two cities in 1830. Since then, it has been an integral part of the region’s growth. And as the modern railway looks towards its 200th birthday next year, plans are being developed to ensure that it remains just as vital to the region in the future.

As Labour finally revealed its plans for rail in April, with its publication of Getting Britain Moving: Labour’s Plans to Fix Britain’s Railways, there was an impression of the many details that it will still need to outline, having now gained the keys to No. 10. This will need to include much of Network North, the collection of projects packaged up by Rishi Sunak after his cancellation of HS2 Phase 2a last October.

Getting Britain Moving also didn’t mention Northern Powerhouse Rail (NPR) - the grand plan to join the northern cities of Liverpool, Manchester, and Leeds through a series of new and existing rail lines.

Since that cancellation of HS2 Phase 2, and the announcement from government that £12 billion saved from not building the line from the Midlands to Manchester would be transferred to Northern Powerhouse Rail (and specifically a high-speed rail link between the two cities), the government and mayors of Liverpool and Manchester Steve Rotheram and Andy Burnham have been looking for the upper hand in any conversation on what that could look like.

We had some indication in March of the future for NPR, when the government announced its next steps. As part of that announcement, a “clear consensus” among local leaders had been expressed to see Manchester Airport and Warrington Bank Quay served by any new rail line.

“We welcome the progress of further engagement with northern political and business leaders. It’s essential that any final route is place-based and meets the ambitions of local leaders for their residents and businesses,” said Transport for the North Chair Lord McLoughlin at the time.

But how did we get here?

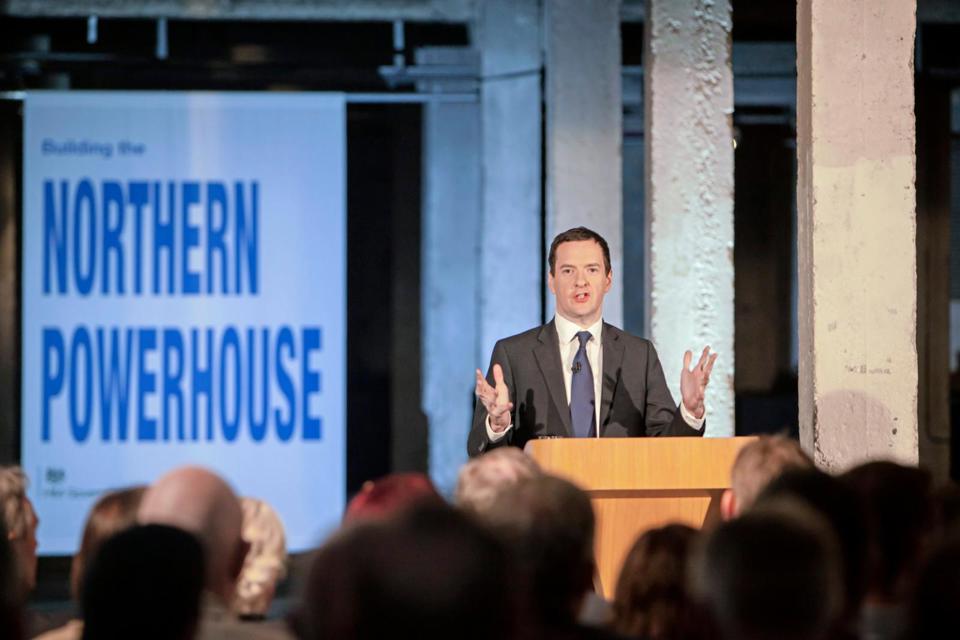

The Northern Powerhouse was the brainchild of the 2010 Coalition government, part of a wide-reaching and ambitious plan of growing the industrial heartlands of the North and connecting its major cities.

The term Northern Powerhouse was first mentioned by then-Chancellor George Osborne in 2014 (pictured above). The initial aim was to build a new high-speed route from Liverpool to Manchester Airport, joining HS2 at a new station at the Airport, before heading into Manchester Piccadilly. From there, the new line would carve through the Pennines finally reaching Leeds, via Bradford. However, NPR then found itself caught up in the Boris Johnson administration’s muddled ‘Levelling Up’ agenda, competing for funding and space in the transport agenda that had been occupied by HS2.

It lost out significantly when the project was curtailed in the Integrated Rail Plan (IRP) in November 2021.

The IRP proposed that the high-speed line from Liverpool would be scrapped. Instead, the existing Liverpool-Manchester southern route would be upgraded, with a short high-speed section between Warrington and Marsden in West Yorkshire, stopping at Manchester Piccadilly. Here it would then join the trans-Pennine route, itself undergoing an upgrade.

But NPR was (and has always been) more than just one high-speed line. Before the IRP was published in November 2021, TfN had argued that the way to unlock the North’s potential was not to hang its hat on one project, but rather to focus on a more inclusive approach. Its plans, originally published a few months before the IRP in June 2021, had advocated for the new line between Liverpool and Manchester, alongside upgrades to lines that served Manchester to Sheffield, believing that would improve passenger times and capacity.

The plans for Manchester to Sheffield connectivity have been partly addressed by the Hope Valley upgrade - although the benefits will take some time to be seen with capacity issues on both sides of the Pennines. TfN also pushed for electrification from Leeds to both Hull and Sheffield, as it sought to include the major urban centres of the North and retain the original vision for a Northern Powerhouse. In the meantime, HS2 continued to make its presence felt, and NPR (as envisioned by TfN) was deemed a stretch too far for the Department for Transport.

Then the landscape changed entirely with last October’s cancellation of HS2 Phase 2a. That shifted focus back to what could be delivered to truly match the vision that the government and regional administrations had of the North’s potential. NPR was suddenly brought into sharper focus, forming a key part of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s Network North plan. Having achieved a landslide General Election victory, Labour will have a decision to make on how it sees NPR being delivered. New Prime Minister Sir Kier Starmer has already ruled out reviving HS2 Phase 2, but he has committed to building NPR in full. However, he has stopped short of outlining those plans until conversations have taken place with the region’s devolved powers. Jonathan Spruce, Institute of Civil Engineers trustee for Policy and Affairs and former interim strategy director for Transport for the North, believes that the lack of a plan has harmed progress.

“There are many disparate transport strategies throughout the UK, for different modes, and for different regions,” he says.

“What we lack, and what we need, are clearly defined transport objectives to align those strategies with the UK’s long-term goals - and a commitment from central government to stay the course.”

Costing a scheme is likely to be as difficult for the new government as for the previous administration, but Labour will be keen to create space between itself and its predecessors.

This will likely mean an expectation that Starmer will want to push ahead with the Manchester-Liverpool Rail link at the very least. However, the route that it will eventually take is still a little unclear. The newly formed Liverpool-Manchester Rail Board (including the two mayors of the cities) outlined its preferred route at the end of May, deciding that a completely new line between Manchester, Manchester Airport, Warrington and Liverpool was the most viable route, although it is a little unclear on how this will fix capacity issues.

HS2’s removal has in some part meant that any NPR line will not solve the capacity issues that plague Manchester’s inter-city network, with some of its value tied to the fact that HS2 would be picking up some of the services and thus releasing space on existing lines. This is especially true of the Castlefield Corridor, the city’s busiest bottleneck. And that bottleneck has only worsened with the opening of the Ordsall Chord in 2017.

While some of the services will undoubtedly move onto the new line, inevitably fast train services will continue running on the Castlefield Corridor.

The capacity problem will likely still exist to a certain degree once the Liverpool-Manchester line is open, simply because the corridor runs in an opposite direction to the new proposed line and will have to be resolved another way (a brand new Castlefield tunnel and line has been proposed to offer relief to the line in the past).

The previously mooted idea of upgrading the Fiddlers Ferry freight line from Widnes to Warrington seems to have been dropped, with Liverpool City Region Mayor Steve Rotheram confirming in March that it was not an option. He had also been opposed to it originally, describing the initial plan presented in the IRP as “cheap and nasty”.

However, if a new four-track line is to be built, and needing to stop at Manchester Airport, it will likely have to carve a very similar route - although as former Rail Minister Huw Merriman remarked in a response to Rotheram and Leader of Liverpool Council Liam Robinson in March, the government was “committed to looking at alternatives to using the West Coast Main Line [WCML] into Liverpool and to review station options as part of the next phase”.

Whichever route it takes, the benefits have long been clear.According to TfN Rail and Roads Director and Deputy Chief Executive Darren Oldham, it is a case of now or never: “It must happen. Manchester and Liverpool are two of the UK’s key cities and the need for those to be effectively connected on a rail route that works efficiently must happen.”

Oldham also believes that there has been a renewed impetus from politicians to finally get the Manchester-Liverpool Rail Link off the ground.

“I don’t see any lack of desire from any politicians in the North West or in Westminster in terms of making it happen,” he says.

As Oldham and TfN know, making sure that both the route and the wider project are right is hugely important. And while TfN hasn’t been given everything it has been asking for over the past decade, a new fully built connection between Liverpool and Manchester is inching closer. This time, therefore, it must be right - and this is never truer than with Manchester.

“Manchester absolutely must be done in the right way to ensure that there is effective connectivity, for travelling in and out of the conurbation,” says Oldham. “It needs to be effective for connections through to Liverpool. But also, just as importantly, it needs to be designed in the right way so that the travelling public - be it from Leeds or further to the East - can travel effectively into Manchester.

“That’s also important for those travelling from the south, be it on existing lines or new lines. So, in many ways, Manchester is fundamental to the effective operation of the transport network of England.” What the right way looks like is still open to debate. But ICE’s Spruce believes that before any construction or engineering works take place, there needs to be better understanding of how to effectively manage projects of this size.

“There are undoubtedly lessons to be learned from the cancellation of the northern leg of HS2 and how the project was planned, managed and strategically communicated,” he tells RAIL. “There are clear themes already emerging from our discussion with key stakeholders and other experts. “For example, there is a need for better corporate governance on who makes decisions and how and when those decision are made. It’s also clear that a programme of work of this scale should spend more time in development.

“However, while it’s important to consider how the cancellation has impacted individual projects such as Northern Powerhouse Rail, it’s potentially more useful to consider what the cancellation shows us about how transport infrastructure is strategically planned in the UK.”

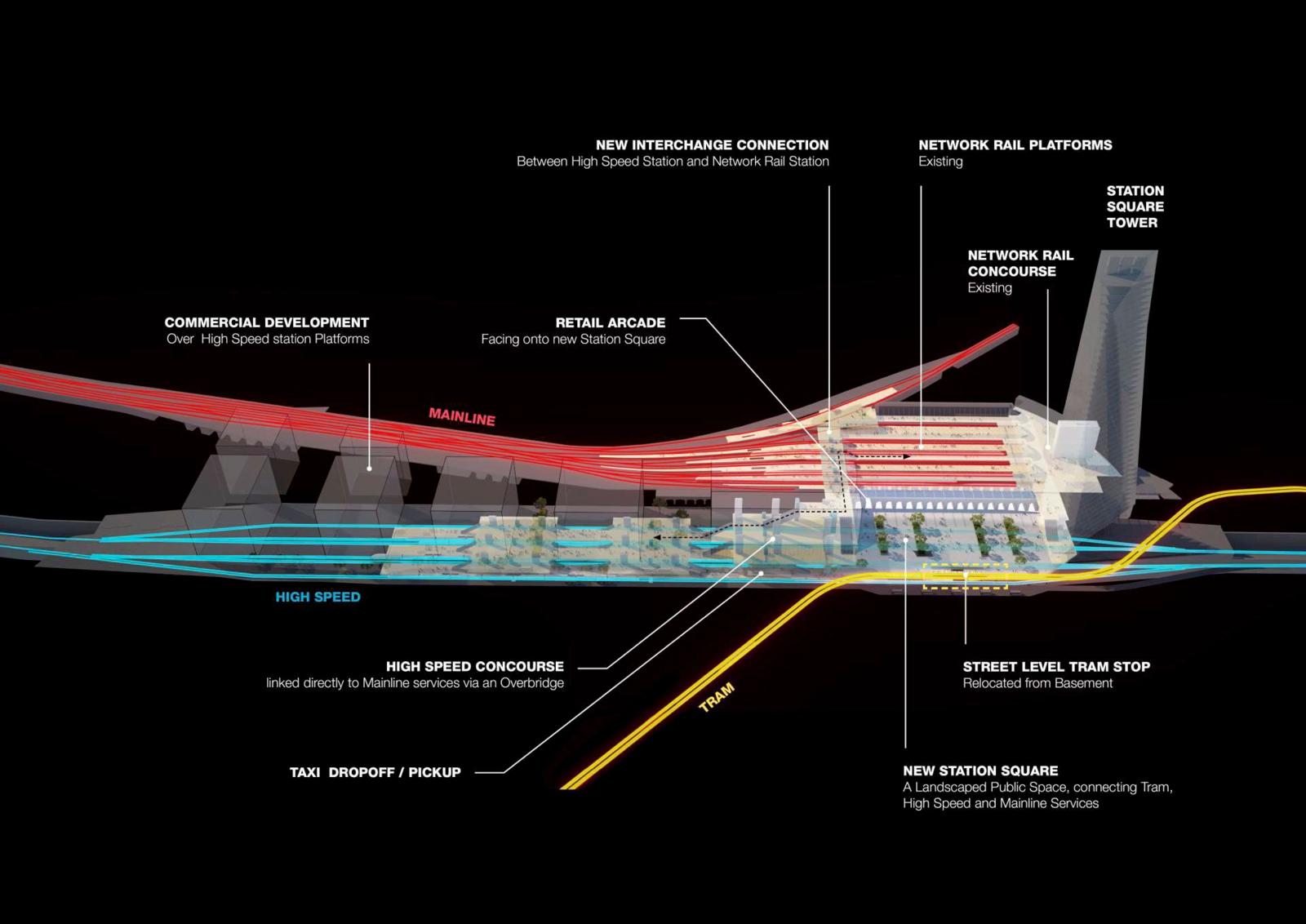

Nevertheless, government and devolved regions seem keen to move forward with the project as quickly as possible, even adapting the High-Speed Rail (Crewe-Manchester) Bill to suit NPR’s needs. In short, the previous government had not changed the route from Manchester Airport to Manchester Piccadilly, just its purpose. But with Phase 2 cancelled, the HS2 approach into Manchester will now have to be costed into the new link’s budget. This leaves the conundrum of what a station at Manchester Piccadilly would look like.

Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham has always wanted a below-ground station at Manchester Piccadilly. It is the only way to ensure capacity can be increased sufficiently, he argues. It would also unlock property opportunities not taken up with above-ground viaducts.However, in initial discussions, the costs proved to be a step too far, and the government went for the cheaper above-ground station option.

But, with this being about second chances, Burnham has seized the opportunity to push his preferred option again. For Chris Pike, UK Rail sector director at Arcadis and a member of the High-Speed Rail Group, deciding what is the right way regarding the below-ground station is a balancing act that should be aimed at compromise.

“Ultimately, whenever we look at projects like this [Manchester Piccadilly], it is about maximising its potential. Local authorities, government and the rail industry will all have different ideas. But what provides the biggest return? What has the biggest benefits?

“The right decision for one interested party may not be the right decision for others.” Potentially, this means that the many voices that are currently working on NPR and the Manchester Piccadilly development will have different end goals. Some are political, some are financial. Somewhere in between is what’s right for the railway. But such discussions will need clarity from whichever government is in place in 2025. The argument for an underground station at Manchester Piccadilly was initially based on the idea that it would be accommodating HS2 trains - originally up to three per hour from London. That would best be served underground, it was argued, to enable the above-ground station to handle suburban and regional network arrivals.

A six-platform approach was the initially mooted idea, which was then scaled down to four owing to cost concerns - allowing for up to 15 NPR and HS2 trains per hour.

But the cancellation of HS2 means that capacity issues, which could have presented a problem for the below-ground station given the timetabling synchronisation needed with London Euston, now need no longer apply. And the originally costed proposal of just over £7bn could be less if new plans are moderated. However, Burnham is in no mood for this to happen. He has, for a long time, said that the capacity for Manchester Piccadilly’s new station should HS2 Phase 2 ever be resurrected. This would presumably also mean increasing capacity for any new line built between Manchester and Bradford. In the end, to fully realise the Manchester-Liverpool rail line and the further ambitions of Northern Powerhouse rail, it will come down to cost.

But for TfN’s Oldham, it’s important that it is also the right scheme, one that finally realises the potential of the region.

“The answer must be the right answer, and not an answer that relates to a timeline or to a budget. Of course, we all must work to budgets, we must get best value. But it’s too important to get wrong. “We have to strike that balance between getting things right and having the optimum scheme, making sure we have something that works well for Manchester, Liverpool, Warrington, Cheshire, but also the rest of the rail network.”

Chris Pike believes that the right solution should involve high-speed rail, but one that truly delivers to an ever-growing region.

“If connectivity is to be realised, we must look at the scale of high-speed options. There is an exponential relationship between speed and cost. The faster you go, the more expensive it’s going to be, and there is an argument to say do you need to run it 360kph [225mph, the estimated speed of HS2]?“Because if you dial that back and you look at the specification that you’re using, there are potentially some significant cost savings to be made.”

With the correct specification, it could improve speed, capacity, and connectivity. According to Spruce, some part of the issue with cost is down to how it is communicated. “We need to explain projects to the public in terms of outcomes, like cleaner air and better transport links between cities, instead of measuring everything in terms of cost.”

Nobody wants to see this project fail and the chance to create the building blocks for a truly connected North are now starting to take shape. If the region and government is going to realise this dream, then they will have to do something they haven’t done very well over the past few years - work together.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.