Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

A few weeks ago I met with Anthony Smith, chief executive of Passenger Focus. Ironically, our meeting was to discuss roads, and the new role that his organisation is set to acquire representing users on the strategic road network. But the conversation moved on - as they do - and we found ourselves discussing passenger priorities for the railway.

What surprised me, although perhaps it shouldn’t, is that the themes raised by passengers are so consistent whenever and wherever they are asked. That is not to belittle them in any way, or to underestimate how difficult they can be to satisfy, but I was struck by how different their views are - both in topic and approach - to those regularly expressed by freight customers.

I was reflecting on this at the Rail Freight Group summer meeting, at which Drax Power, one of rail freight’s larger customers, set out its expectations and priorities for rail freight.

The list was distinctly different from those expressed by passengers, focusing on cost efficiency, management of network capacity and securing return on investment. But ask a user in the retail sector what their issues are, and you will get a different list again.

So what do freight customers want? And how are we, as an industry, responding to that?

The rail freight market today

To understand why freight customer views differ, you need to start by understanding the market.

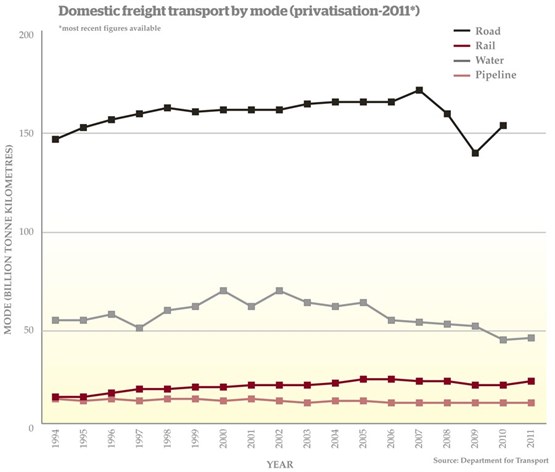

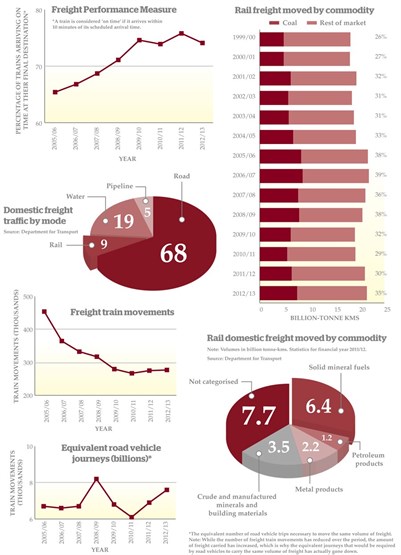

Today, around 22 billion tonne-kms of rail freight is moved, up 6% in the last year. Research from the Rail Delivery Group shows that the value of the goods moved is over £30 billion, and that collectively the sector contributes over £1.5bn to the economy, keeping 7.6 million lorries off the road.

Yet the rail freight market is not homogeneous. The different sectors that contribute to that total face very different market conditions, future trends and supply chain needs.

Coal, the traditional bedrock of rail freight, still represents around a third of all business. Because domestic coal production has mostly ceased, with the exception of the Scottish open cast business, the vast majority of traffic now links ports and power stations rather than the traditional flows from mines.

Many ports are involved in the supply of coal, including east coast locations such as Immingham and Hull, and Bristol and Liverpool on the west coast. Traffic runs to the large coal-fired power stations, such as Drax, Ferrybridge, Fiddlers Ferry and Cottam.

As you would expect, coal movement is seasonal as power demand rises and falls with the weather. The share of coal generation is driven by the relative prices of coal and gas (the latter is particularly volatile).

Supply chains are also complex. To ensure security of supply, power stations use a diverse range of ports and rail operators, booking deliveries across them on a week-by-week basis. Little wonder that coal flows are so complex on the network!

Coal generation is under pressure from environmental legislation, and we have recently seen a number of power station closures - including Didcot, whose landmark cooling towers were demolished in July.

However, the remaining fossil fuel power stations still have a decade of useful life ahead, and the recent Budget made changes to the rate of carbon tax that appear likely to stabilise coal generation over the coming years. It is of note that last winter, coal generation accounted for almost 40% of all UK electricity needs, despite a rise in the share of renewables.

Coal is not the only commodity moved for the power sector. Partial or full conversion of some generators to handle biomass (pelletised wood) has opened a new market for rail freight, and necessitated significant investment in wagons and loading facilities to accommodate this new fuel. It is still unclear how many generating units might convert, but with government support confirmed to 2027 for those that are, there will be significant opportunities in this market.

Away from coal, the other large bulk commodity group is construction materials. Last year this grew by 17%, as the economy pulled out of recession and building activity began to resume.

Materials moved include stone (limestone and granite), sand and gravel and cement used in the building industry, as well as other smaller flows of gypsum, pulverised flue ash, construction waste and other materials.

The movement of construction materials on rail owes much to the nation’s geography. Hard stone mainly occurs north of the so-called ‘stone line’ that extends from the Severn estuary to the Wash, while sand and gravel occurs to the south.

As the foolish man discovered to his peril, you cannot build a house on sand, so hard rock must be imported to the London and South East region to support any kind of significant construction activity. Hence the main rail flows come from the quarries in the Mendips, East Midlands and Peak District to terminals in the South East. Increasingly we are also seeing flows into other conurbations such as Manchester and Leeds, while sand and gravel moves back in the other direction.

Rail’s increasing role is also being influenced by the minerals planning regime. Getting new extraction consents is difficult and costly, so as smaller and older quarries become expired, there is more focus on the larger sites with longer permissions. This tends to work to rail’s benefit, as haul lengths from these ‘super’ quarries to market are greater. This trend has already contributed to the sector’s growth in recent years, and we expect it to continue.

Away from bulk, the largest sector is intermodal, which today makes up a further third of all traffic.

This is actually two distinct markets. First (and by far the largest) is the movement of deep sea shipping containers from port to terminal, dominated by the large flows from Southampton, Felixstowe and London to inland destinations across the UK.

These ports dominate because the global shipping lines such as Maersk, using the world’s largest container ships, tend to only make a single UK call on routes between the Far East and Americas to mainland Europe, and do not want to sail far from the shipping lanes taking them on to ports such as Rotterdam.

Of course, other ports do handle containerised goods, including traffic coming on feeder vessels and other short sea trades. The Port of Liverpool is presently investing to enable ‘new post panamax’-size vessels to call there, while several of the East Coast ports also handle container flows.

But for rail the combination of volume and destination has (at least to date) made this difficult business from the regional ports, although all eyes are on Liverpool at present.

On the main flows, however, intermodal volumes have soared - up 75% in the decade to 2012. There is little doubt that work to ‘gauge clear’ the network, allowing 9ft 6in standard containers to be conveyed, has made a big difference.

Increased efficiency and competition in the market has also caused costs to fall, making rail more able to compete with road. We expect these trends to continue, and there is certainly significant potential for rail to increase its market share in this sector.

The second part of the intermodal market, so-called domestic intermodal, is the movement of goods for the retail sector within the UK mainland. This is still a small market on rail, but one where there is huge potential for growth.

Retailers rely on a series of national and regional distribution centres, from where they supply their store networks and ecommerce businesses.

Some, such as Tesco, are finding that they can use rail on the trunk flows between these centres, and in some cases even direct to store.

To date, this has tended to work best through third-party logistics providers such as Stobart, which help to co-ordinate loads and maximise train fill.

On the right flows, they are finding that they can compete on price (even compared with double-deck road trailers), and meet reliability and journey time requirements. The key, however, is locating the warehouse as close as possible to the rail terminal, which is why the majority of the traffic today originates from the strategic rail freight interchange at Daventry, and why there is pressure to develop other similar sites elsewhere.

There are, of course, too many sectors to mention individually, with others including Channel Tunnel freight, steel, waste, Royal Mail and automotive. It all paints a picture of rail freight not as a homogeneous sector, but as a series of distinct markets. For rail operators, and for the rail sector as a whole, understanding this and the respective customer needs is critical to success.

The changing role of customers

Rail freight flows are complex and varied, involving multiple parties. Even identifying who the customer is can be complex. Is it the owner of the goods, or the freight forwarder, or the shipping line? The terminal operators play a major role, but may not own any of the goods. Is the port or the power station the customer of a coal flow? Simply, we might consider they all are!

The level of engagement also varies significantly, with many customers content to let their rail operator represent their interests. But as the market for haulage has become more competitive, there has been an increasing trend for some customers to seek a greater role in determining rail strategy.

This has been particularly linked to investment. The freight operators such as DB Schenker, Freightliner, GB Railfreight and others have invested over £2bn since privatisation in rolling stock and facilities, as well as in systems and technological improvement. Alongside that, customers have invested significant sums in their own facilities.

Recent examples include Port of Felixstowe’s investment of £40 million in the North Rail Terminal, and London Gateway’s extensive rail facilities. Drax Power has bought new rail wagons and upgraded its internal rail lines, as well as supporting investment at Port of Tyne and elsewhere. Prologis is investing heavily in rail-linked facilities at Daventry, with Phase 3 recently receiving planning consent. Potter Group is extending the headshunt at its Selby facility, to take 775-metre trains. And there are many other examples.

This investment often goes unnoticed, but without it rail freight would not be progressing as it is.

And yet if you are a major port, for example, you might consider such investment a leap of faith. You have no control over rail paths on the network. There is no way of securing capacity to enable your investment to be used in the future. The access charge process is profoundly complex. You’re not even consulted on network changes that might affect your traffic, while engineering work schedules are planned at whim.

This is not in any way to criticise the rail operators who work tirelessly to represent the needs of their customers in all these areas. But as rail freight becomes increasingly competitive, many customers are seeking their own relationships with government, Network Rail and the Office of Rail Regulation, to gain influence.

The key issues

Despite the diversity of the market, some common customer priorities are emerging.

Top of the list is cost. For freight customers, there is a much closer correlation between operational costs and the price they actually pay than there is in the passenger sector. So, for example, Network Rail’s efficiency targets have little (if any) impact on rail fares, but make a direct impact on rail access charges and hence costs to customers.

For elastic markets such as intermodal, rail must compete directly on cost with HGVs. The road market is fast moving, competitive, flexible and (with road fuel duty now held for a fourth year) increasingly cost-effective. Customers such as Tesco price check on a regular basis, and will revert to road as soon as the cost margin tips even a few pence. Rail has different advantages, but they are all secondary to the bottom line.

Even in sectors such as coal, and perhaps steel, where some goods are captive to rail, costs are still a major consideration.

Transport prices influence decisions over where facilities will be located, upgraded or closed. And in a global economy, the decision whether to invest in the UK or elsewhere is nudged by many factors, of which transport is one. So while these customers are unlikely or unable to use road, they are still keenly astute on rail costs.

A key element in reducing costs is increasing the efficiency of rail freight operations. There have been significant gains in staff productivity, asset use and train loading. There are a third fewer freight trains running than a decade ago - yes, fewer - and yet each train is moving more than 50% more goods than it did then. Longer, better-loaded and heavier trains are becoming the norm across the network.

But there is still far more to do. Average freight train speed is a derisory 25mph, and is worse in some cases. If trains sit idle in loops they are still consuming both fuel and driver hours, limiting the number of daily trips each locomotive and wagon set can make. As trains get longer and heavier, their ability to easily accelerate and decelerate in and out of loops is compromised, which brings performance risk. And on top of this there can be inefficiency in terminals and ports, which is often compounded by poor alignment of network and terminal capacity and performance.

This is not easy to unlock, but if rail freight is to take the next step in efficiency - and, dare we say it, pay any more for access - this must move forward. Customers are beginning to understand the issue and to play their part in finding solutions, but it requires collaborative working between Network Rail, operators and customers.

One of the reasons why asset use is difficult is because rail freight is restricted (for good reason) during the passenger peaks, and then constrained overnight by engineering work schedules. You can use a lorry 24 hours a day, but rail has much lower availability.

Over time there have been numerous studies on efficient engineering work (most recently from the Rail Delivery Group), concluding that more work is needed at weekends, or overnight, or in short blocks, or long blockades, and so on. Yet there seems to be little progress in arranging the work to enable freight (and passenger) trains to keep moving.

Even where diversionary routes have been provided, Network Rail seems incapable of scheduling work to keep one route open at all times. The Port of Felixstowe sees 60 daily trains Monday to Friday, but not a single one on Sundays, as the engineering schedules cannot guarantee a path.

Customers cannot understand this, and are frustrated at the seeming indifference to opening up this capacity for their use. It is particularly vital for the retail sector, which needs Sunday deliveries for store replenishment.

Making more use of capacity at weekends and overnight may seem to be an impossible challenge to some, but as the rail network becomes increasingly constrained it is surely a must.

Ports and developers planning to construct rail-linked facilities need to understand that they can get a return on their investment, running the services they expect on the network, not just today but also in the future.

As the network gets more and more full, there is a danger that investor confidence will be undermined by the perception (if not the reality) of limited capacity. This is why we are pressing for early certainty over the freight benefits that might be delivered by HS2. We are also keen that Network Rail continues to make progress on delivering and securing strategic freight capacity on the core routes.

Suppliers

Although we have talked mainly about rail freight customers, the supply sector is equally vital to the success of the industry.

Modern locomotives and wagons are critical to achieving enhanced payloads, improving acceleration and braking, and delivering efficiency. Handling equipment, cranes, reach stackers and such like can make the difference in terminal operations, while digital technology also has a major role to play.

The supply industry has invested in research and innovation, but will only do so where it is confident it can make a return, and (like freight customers) its voice is perhaps underplayed in the debate. Perhaps this is an area for the newly established Rail Supply Group to pick up.

Making progress

Despite the challenges, there are encouraging signs of progress. Network Rail’s freight team has committed more time and resource to end customers with positive results, collaborating on projects such as control rooms at Immingham and Drax to encourage right time performance.

End customers are becoming more aware of wider sectoral issues, helping to inform their decision-making and to understand the challenges and opportunities faced.

The operators are becoming increasingly comfortable with the new order, and are working together more than ever before. And even the ORR has promised a freight customer panel.

Recognising the voice of the freight customer isn’t just a ‘nice to have’, it’s how we will unlock the true benefits of the competitive, private rail freight sector. Working with the rail operators, a collaborative approach is the only way to achieve the next tranche of efficiency benefits, and to secure ongoing investment.

And understanding the diversity of rail freight customers, and why they expect something so different from the rail passenger, is an important education for all in our industry.

Peer review: Mike Jones FRSA FCILT

Peer review: Mike Jones FRSA FCILT

Former Railfreight National Business Manager

The overriding success of the freight operating companies has been their drive to improve productivity, in noticeable contrast to the passenger operators. This is a result of investment in efficient traction and rolling stock, terminal facilities, and flexibility in the way staff are employed. The subsequent lower costs have allowed greater competitiveness for flows that would otherwise not have been attracted to rail.

The role of the Government’s Mode Shift Revenue Support (MSRS) grant regime should also be acknowledged. This takes the form of a direct subsidy for the movement of bulk tonnage and containers where the price of road movement is below that of rail. The scheme is justified on the basis of societal benefits, in removing heavy goods vehicle traffic from the roads, and has an annual budget of £18.6 million.

There was a degree of good fortune for the freight operators, in the switch from locally produced deep-mined coal to imported supplies, which has created long hauls from ports such as Hunterston, to power stations. The structure of the privatised industry enabled substantial investment to take place to meet these needs, with the availability of equipment financed by leasing companies.

The number of licensed operators also produces a competitive market that drives innovation in response to tenders.

It is an outstanding statistic that despite continuing growth, the number of train movements has been substantially reduced. This does mask a product weakness, however - apart from the containerised market, which might be seen as a retail business, the increased size of trainloads means flows that may be substantial in road haulage terms cannot be conveyed competitively by rail.

A solution has been tried in the form of a freight multiple unit. And although successful operational trials were carried out, the freight operators have shown little interest in a product that would allow smaller trainloads to be competitive in terms of both the market and winning paths on a congested network.

Maggie Simpson is right to draw attention to the failure of the seven-day railway concept that Network Rail evolved to address the limitation of times when freight trains can be run. In reality, the continuing growth of the passenger railway and demands for greater reliability means it is unlikely that the need for engineering possessions outside the hours of the timetable will diminish.

The solution has to be greater investment in diversionary routes that can be used by freight trains, such as the Joint Line between Peterborough and Doncaster and the type of re-routing possible when the East-West Oxford-Bedford route is commissioned.

There is only passing reference to the potential for international traffic using the Channel Tunnel. Various factors have been put forward to explain the lack of business, and although the tariff structure has recently been made more competitive, I suspect the greatest constraint is the lack of commercial expertise in meeting the requirements of a market dominated by road haulage.

The outstanding opportunity for continuing productivity is the use of electric traction, as the national programme for overhead wiring will give greater network reach.

At present there is no sign that the freight operators are contemplating any change from their current ‘diesel under the wires’ strategy. However, the order for ten new electric locomotives by Direct Rail Services may be the start of a change in this trend.

Peer review: Cameron Taylor

Peer review: Cameron Taylor

Primary Account Manager (Rail), Tesco

Maggie Simpson asks the question: “So what do freight customers want?” And indeed she goes on to answer that question very well.

For the retail intermodal market the answer is fairly straightforward: a customer-focused operation that is reliable, flexible and cost-effective. It seems simple enough, but to achieve this we must have a strong working partnership with a logistics provider (ESL), a rail operator (Direct Rail Services), and, of course, suppliers.

The right product has to be at the right place at the right time. As Maggie points out, this can be a distribution centre or a store. Either way, staff are waiting to deal with the stock - therefore on-time deliveries are crucial to ensure productivity does not suffer and customers can get what they want.

If a road driver calls in sick, the net effect is that one load may not travel. If a train driver calls in sick, we have a situation whereby up to 36 loads may not travel. This situation led to a long-held belief in logistics that rail was not reliable enough for retailers, but this is being proved wrong - every day of every week Tesco sees full trains depart and arrive on time.

This is due in no small part to our rail operator. They understand that as a customer we expect them to deliver, and when issues arise they need to react to minimise any impact on our operations.

As we know, today’s customers demand a 24/7 operation. However, as Maggie points out, rail freight customers are frustrated and cannot understand why Saturdays and Sundays seem to be an issue. How can rail freight hope to compete against road if we can’t move for 36 hours?

Of course, there is some Sunday traffic. But much of the time it can’t run due to possessions, and it seems inconceivable that we can’t get a path out of Scotland on a Saturday night or get a timely northbound path on a Sunday.

Increasing weekend capacity can only be good for customers of rail freight and operators alike. Customers can get the product to where it needs to be, and operators can use assets more productively.

After all, a haulier does not buy a tractor unit just to have it sit idle for 20% of the time. Keeping the wheels turning brings cost efficiencies, and this must be at the forefront of rail freight’s thoughts. More and more retailers make use of double-deck trailers, and rail freight has to measure itself against this rather than the conventional trailer.

There is no one size fits all for retail customers in rail freight. Each one demands a bespoke solution, and if the rail freight sector wants to unlock more of the market - such as fresh and frozen food - then this is what it must be willing to offer.

Peer review: Mary Bonar

Peer review: Mary Bonar

Consultant, Bevan Brittan LLP

Maggie Simpson has provided a comprehensive update on the different sectors and needs of the industrial and retail market interested in putting their raw materials and goods on rail.

The underlying message is that the commercial organisations have (in most cases) plenty of choice of mode and even location. They are driven by cost and efficiency. It is for our politicians and society, not merely the rail freight operators, to understand the benefits of putting more freight on rail and to make the offering sufficiently attractive.

A 6% increase in tonnes-km moved by rail last year sounds impressive. Linking this to the number of road (lorry) miles saved would be a useful measure in explaining to politicians and voters the wider benefits of increasing freight on rail. It’s one of the areas where more needs to be done - for example, to help sell the benefits of HS2 to people who get all the disadvantages of the line disrupting their area, but none of the direct benefits.

The rail freight market (like the road freight market) is completely different to the passenger market - the freight customer nearly always has an obvious alternative in using road haulage, or in specific cases of changing the location and country of its operations..

This brings the key issues that Maggie Simpson has identified into focus. The underlying point, one that I agree with, is that there is still a long way to go to make the way the UK rail network is regulated and operated sufficiently attractive to make a real impact in getting freight off our roads and onto rail.

In 2007 the Office of Rail Regulation held a consultation into track access options, and a policy was issued in January 2008.

Most of the organisations that took part were interested in the freight market, but the main immediate output was the Crossrail Track Access Option. The policy does, however, provide an answer to the question of how a port or freight facilities developer could ensure that paths are available for the use of the facility to underwrite the return on investment. This is conditional upon there being sufficient capacity on the Network Rail network.

The market changes identified suggest that it is time for the regulator to look again at this policy, as well as monitoring and enforcing the delivery of the efficiency targets it has just set for 2014 to 2019.

Peer review: Nick Gallop

Peer review: Nick Gallop

Managing Director, Intermodality Ltd

Despite significant progress by Government, the industry and end users, much work remains to be done if the untapped potential for rail freight is to approach anywhere near the level of forecast growth.

Where there was once only one choice of rail freight haulier (BR), now there are several to choose from. Yet most of these will source their wagons and locomotives from the same places, have traincrew on similar terms and conditions, and obtain broadly the same rates for fuel and track access.

If each is to grow their own market, rather than simply poach customers from each other in a race to the bottom on price, the challenge will increasingly be to differentiate - on performance, or margins, or individual service offers based on different types of traction, rolling stock and bolt-on value-added services, such as terminals and road haulage.

With most of the traditional core traffic flows in the bulk sectors being mature or potentially in long-term decline, there are several new markets to tap for rail in the non-bulk sector, including sectors where rail used to have a presence. These will require new mindsets as much as service offers, as the customer requirements can be more demanding, while current traction and rolling stock may not be suitable or in sufficient supply – examples include car-carrying wagons, high-cube conventional wagons and high-speed wagons. Cracking these markets will require a bold and highly entrepreneurial view on performance, as well as investment risk.

There is no doubt that the work being done by Network Rail on upgrading the rail network to cater for taller and longer trains is yielding results that Government cost-benefit analysis would not have predicted. No one is denying that such works require significant levels of investment. Yet comparisons with other countries repeatedly indicate that the cost of maintaining and enhancing the GB rail network remains stubbornly high, suggesting further work is needed to embrace global best practice without compromising safety.

In parallel, recent reductions in cross-Channel access charges should help stimulate this obvious but under-performing sector of rail freight. Yet this alone will only achieve so much if it remains stubbornly difficult to secure reliable train paths through France, or in turn to achieve seamless pan-European (and now pan-Eurasian) transits that can compete head-on with road haulage and shipping.

The ports have shown how investment in rail facilities can make a significant contribution to smoothing the flow of freight through major import and export gateways.

Where the planning system has allowed, so too have property developers, with inland terminal developments such as DIRFT and Hams Hall. It is hoped that the new planning regime, which has helped expedite consent for the third major expansion phase of DIRFT, will be similarly able to process other inland terminal projects in a similar fashion, to once again create a vibrant and well-populated network of inter-connected terminals, able to reinvigorate the market for domestic rail freight.

Maggie also refers to speed, which should be one of rail’s key unique selling points, particularly in the face of a congested road network and retailers wanting to achieve the holy grail of ecommerce – same-day delivery. 25mph is simply not good enough when trucks can average twice this speed, and freight trains can travel at up to four times this speed when allowed.

Speed is a challenge for timetabling planning, traction and rolling stock, but get it right and road haulage won’t be able to come close!

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.