It will be news to nobody that there is a skills shortage in the rail industry. This well-trodden ground has been the subject of many a conference speech and magazine article over the past few years.

It will be news to nobody that there is a skills shortage in the rail industry. This well-trodden ground has been the subject of many a conference speech and magazine article over the past few years.

But there comes a point when admitting we have a problem and quantifying the size of it can only get us so far. Continued investment in the railway will only be worthwhile if we take action now to ensure that the workforce and expertise is put in place to deliver on our ambitions.

We’re suffering from the legacy of past underinvestment in transport and its workforce, preventing skills from being handed down to the next generation and stifling the flow of new and young people onto the railway.

In more recent years, rail has enjoyed significant Government investment, but will this continue?

National Skills Academy for Rail Chief Executive Neil Robertson warns that our skills shortage could create a vicious circle here: “The Treasury is very reluctant to invest in rail because they think we are overheated. They think we have skills shortages and wage inflation. I’ve been saying this for six months, and I think the Autumn Statement and recent Budget proves it.

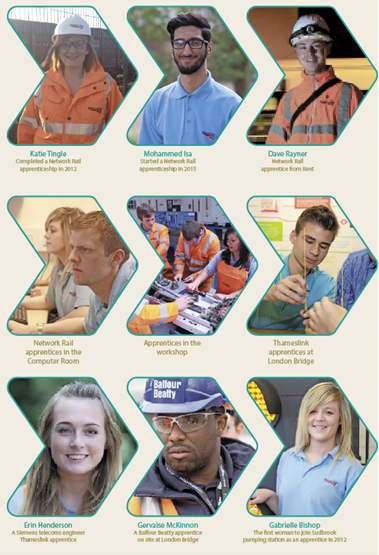

“So there is a really, really important job for rail to do, which is to acknowledge the problem and then do two things: firstly, tell a very convincing story about what we’re doing on skills to make things better, which is primarily training lots of apprentices; and secondly, how we are working together as an industry to smooth peaks and troughs in demand to give companies a longer-term view, so they are incentivised to invest in people and innovation.”

Rail has a higher wage inflation than any other sector - a fact that Robertson says the Treasury is well aware of. But why is this more prevalent in our industry?

“Three reasons: shortage of people; unions (getting above inflation pay increases); and a good thing (which makes us look bad in the figures) is what the economists call the concentration effect - we’re already starting to see a move higher up the skill levels. There are fewer of the Level 2 jobs and more of the Level 3/4 highly-skilled jobs , so those people are naturally more expensive. We’re moving up the value chain, which in many ways is a good thing, but it looks bad in the figures.”

In the railway’s favour is that we have the best data on skills of any sector at the moment. And there is significant evidence that people in rail are not only keen to act on this, they are actually getting on with it. There is goodwill towards solving the skills shortage, which is half the battle.

Robertson explains: “We’ve got the bit between our teeth and, to mix metaphors, our husky dog sledge is starting to move. But it needs to move further and faster. We’re doing the right things, but we’ve got to do more of them and more quickly. So get on with it, because telling a good story and showing some early green shoots will only take us so far. The Treasury will only believe it when they see it in the figures. So, by the end of 2017, we need to have lots of new people signed up on apprenticeships.”

Essentially, the only thing rail can do to improve the story to the Treasury is to take on more apprentices - they earn less, bring the average wage down, and reduce the wage inflation caused by skills shortages (which is probably about a third of the inflation issue). Our relationship with the unions also plays a big part in this.

The Government is taking its own action to resolve some of these issues, and Robertson is optimistic about this involvement: “It’s unusual because the Government is really getting alongside industry and really getting involved in terms of skills. I can’t fault it, and I’m a man that says when it’s good and when it’s terrible!”

The biggest change this year is the introduction of the Apprenticeship Levy (see panel, page 73), which begins at the start of the new financial year in April. For many big companies this brings huge costs, but one of the main areas on which NSAR is currently focusing is providing advice and assistance to show businesses how they can optimise their levy and achieve the best return from it.

In many ways rail is leading in this area - NSAR’s bespoke levy planner has already been bought by other industries. The aim is to help businesses understand how much of the levy they can get back and how to create a high-level plan for using it.

However, encouraging businesses to invest in skills is easier said than done in an environment where there is a lack of clarity and certainty over future demand and investment in rail. Resolving the skills shortages in the industry cannot just be about what individual companies can do to help - there is an onus on Government to play its part more effectively.

In a report released in February (Staying on Track), Balfour Beatty claimed that the lack of an industrial policy for the railways will drive skilled engineers into other sectors, and that this is preventing the supply chain from investing in technology that would increase productivity, because of the uncertainty about future available work.

The knock-on effect is that rail loses or fails to develop the skills required to deliver projects such as HS2 and Crossrail 2.

Says the report: “The ambitious upgrade and enlargement of the UK’s rail infrastructure has the potential to drive economic expansion and provide employment opportunities for thousands of people for years to come.

“However, the future success of the rail industry is inextricable from the continuity of funding - and thus project flow - provided principally by Network Rail. This is because the investments required of its supply chain partners in existing and future skills, as well as in R&D and critical strategic equipment, cannot be justified without greater demand visibility and certainty.

“The projected stop-go pattern of the project pipeline - a function of Network Rail’s funding model and, in a way, its perceived performance - must be addressed and resolved as a matter of urgency. This will require the examination of better partnership ways of working, which are already proving more efficient, as well as potentially more innovative sources of funding.

“Otherwise, skilled engineers - be they about to retire, much in demand by other industries, aspiring recruits or foreign workers - will be lost to sectors with more reliable, steady pipelines of work. The same forces will also restrict investment in new innovation and productivity.

“Such loss would intensify the already serious constraints facing the rail industry and put in question the efficient delivery of the Government’s intended infrastructure enhancements, with all their benefits.”

Robertson is in agreement with this. He says that we have a problem in this industry investing in our people and innovative technologies because we lack the confidence - there are too many peaks and troughs in work, and this is exacerbated further down the supply chain. For Robertson, this is a key area where he wants NSAR to help, by providing data.

NSAR has been tasked by the industry with setting up a strategic forecasting model to measure, monitor and manage the national skills supply and demand, and provide intelligence by business unit, project, skill set or geography to inform investment needs.

This will allow the industry to establish a baseline, factoring age, gender and the skills profile of the current workforce. It will analyse expected rail investment, changes in technology and productivity gains, to understand future demand.

The Government has set a challenge to create 30,000 new apprenticeships in transport by 2020 (20,000 of them expected to be from the rail sector). Achieving this will require a proactive approach to changing the perceptions people have of the industry, particularly to encourage a more diverse intake than our current make-up. So what is this baseline study, and how will it help to achieve this goal?

“It is the biggest ever skills study,” explains Robertson. “This is a report which will be a cut of the data as of today. There are very few surprises, which is good because we’ve validated that a lot of our assumptions are correct.”

At the time of speaking to RailReview the baseline was not yet published, so Robertson would not be drawn on the finer details of its content. But he did say that it will contain some encouraging signs - it is certainly not all ‘doom and gloom’, with positive indications on gender and skill levels.

The baseline will give us the best database we have ever had, allowing us to answer just about any question on today’s workforce and our future needs. The idea is that every year, we measure ourselves against the baseline to establish how far we have come and how much further we have to go.

The accuracy with which future demand can be identified will tail off through the years, because projects tend to be signed off five years in advance, but even allowing for that, the rail sector already has more clarity on future demand than any other industry.

Understanding where the peaks and troughs are in demand for skills across different sectors would allow the Treasury to build a picture of the whole construction industry, enabling it to commission work for a sector experiencing a trough while there is a peak elsewhere. Of course, this will only help with the non-specific skills - it will make little difference to the ebb and flow of demand for rail-specific skills.

This becomes all the more important because the roads, energy, telecoms and house building sectors are also experiencing growth and skills shortages. The concrete pourers, welders, plant drivers, bridge builders and road builders of this world will all be needed… by all of us. And Brexit is only going to make that worse.

Says Robertson: “Up to half the workforce (around 46%) in the southern half of the country are from a non-UK EU background. This has been confirmed by all kinds of construction surveys. How many of them are going to go or stay after Brexit? Who knows. There are some that have already gone.

“In the Autumn Statement, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) prediction showed that the EU workforce will approximately halve. That means we could lose a quarter of our workforce. That’s both bad and good. It’s good because it creates opportunities for local youngsters to get good, well-paid work. It’s bad because we’re not training local youngsters at anything like the rate.”

Robertson says we are therefore likely to lose about an eighth of our total workforce. But he is surprisingly optimistic about this, because it presents a real opportunity provided we train more people. He believes the Apprenticeship Levy will incentivise this.

Balfour Beatty’s report raises the same concerns about loss of skills from the EU, but is less optimistic about the short term because it can take a decade or more to train a highly-skilled specialist engineer.

“Uncertainty around the free movement of labour in the EU could increase the industry’s recruitment and staffing difficulties, as it may no longer be able to handpick highly-skilled engineers from other EU countries as is currently the case.

“In November 2016, more than 10% of the Balfour Beatty workforce held non-British EU passports, and around 11% of new recruits in 2016 held non-British EU passports. Around 100 of our 2016 recruits came to us via a proactive campaign targeting Greece and Portugal, with a further 40-50 expected in 2017.

“In our supply chain and the people who actually build tomorrow’s infrastructure, the proportion of non-British EU workers is even higher. Only 0.2% of our 2016 recruits come from outside the EU, due to the complexity, cost, administrative burden and time delays required in managing the current points-based sponsor licence system. There is also currently a global shortage of engineers.”

The latter point makes Robertson’s view that we have an opportunity to ‘grow our own’ even more vital - perhaps we need an element of pain to incentivise change.

Technology advancements such as the implementation of the Digital Railway and the introduction of new trains will require us as an industry to have more highly-skilled people, either by training new people to a higher level (something that is already under way by the creation of new apprenticeship standards) or by the upskilling of the existing workforce. So signalling engineers become digital signalling engineers, for example.

Digital skills are also in short supply, so this is not an easy task. Robertson’s advice on this is simple - we need to increase the skill levels of the current workforce because the current levels will not serve us well in the future.

However, he thinks that Brexit could have a negative impact on rail’s wage inflation issues: “Immigration has kept wages lower than they otherwise would have been in the construction and semi-skilled sectors (not in the rail specialist sectors). It has been easier to take on Eastern Europeans rather than innovating and trying to do things differently. So in many cases we have continued to do the same thing, the same old ways, but we’ve got Polish people to do it. Brexit will mean they have to do something differently.

“Many are now working to create the long-term view through the Industrial Strategy - because you will not invest in new ways of doing things or in training people unless you have a reasonably confident view of the future. That’s the most important question - how can we create long-term confidence so that people can invest in kit and people?”

NSAR’s baseline study will give the industry the best springboard it has had in a long time to incentivise and assist credible action on skills. But it will be just that - a springboard - for others to take action from.

“I’ve been doing this sort of stuff in different sectors for a long time, and it is the most exciting time I’ve had in a long time. Because we’re really making a difference,” says Robertson.

“The framework is in place. The strategy is in place. People just need to roll up their sleeves and just bloody get on with it. It’s good to see that many already are.”

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.