Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

Britain’s track owner is a nationalised company. It has been since Network Rail took over from Railtrack in 2002.

Between then and the reclassification of NR’s debts onto government’s books last year, the pretence was maintained that NR was a private company. Now it is beyond doubt that it is nationalised, with its chairman answering directly to the Secretary of State for Transport.

And there have been many questions to answer, chiefly surrounding the state of the company’s enhancements programme. While day-to-day running has presented few major problems and little comment, NR’s upgrade work has attracted plenty of critical headlines. London Bridge station’s remodelling has not gone well, with chaotic scenes of crowds of delayed passengers. Electrification projects are running late - and over-budget. And there is continuing uncertainty about signalling upgrades.

The situation inevitably leads to calls for “something to be done”. In examining what exactly could be done, attention should be paid to both the problem and potential answers. The problem could be structural: Is an overarching single company responsible for all aspects of rail infrastructure, its operation, maintenance, renewals and enhancements the optimal solution? Should the company be split by function? Or by geography? Or in some other way?

If it’s not considered to be a structural problem, is it then a problem of skills and performance? Or volume of work?

Many of the structural challenges were closely examined during the Conservative government’s privatisation planning work in the early 1990s. There was plenty of tension between the Department of Transport (DTp) and the British Railways Board (BRB) in that period. The Treasury was also closely and inevitably involved, with one eye on the money and the other on its usual ambition to control all government departments.

The DTp built four options: Unitary privatisation of BR complete; by business sector (InterCity, Network SouthEast, Regional Railways and Freight); by Region; and by a combination of track authority and train operators. The BRB was pushing a fifth option… that of a National Rail Authority that would contract out services such as engineering, and franchise or sell lines and routes. It would have a holding company to own the track, and make strategic decisions.

Railtrack and Network Rail

Government opted for the track authority and train operator option, by creating Railtrack and selling franchises to private operators. Fast forward two decades and with Railtrack having been sold and gone bust, and its successor (Network Rail) now being owned by government, it can be argued that NR is the National Rail Authority, albeit with some of the grand strategic functions held by its parent, the Department for Transport.

Railtrack was created on a central board plus regional fiefdom basis, in a mirror of the BR structure before sectorisation. It contracted out most of its services, so that private companies provided the bulk of its maintenance and renewals work.

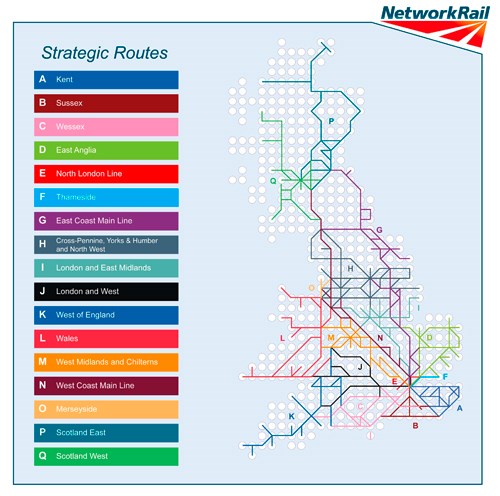

That structure remains today. Railtrack named its geographic areas ‘Zones’ (which differentiated from the Regions that BR had used). NR has ‘Routes’ that remain geographic and broadly match what has gone before.

Overlaid is a national ‘Infrastructure Projects’ (IP) group that is charged with delivering enhancements and renewals, leaving the Routes to concentrate on operating and maintaining the railway (maintenance having been brought in-house, whereas Railtrack had let it to contractors).

This leaves the Route Managing Director (RMD) responsible for running the railway on his patch, but not responsible for the major work that has so often prevented the railway from running. Over-running engineering work - a plague on Monday mornings, and making the headlines last Christmas at King’s Cross and Paddington - remains a major culprit for the railway not being available to passengers.

RMDs should play a much bigger role in enhancements. They are the senior NR managers closest to NR’s customers, but on recent evidence they appear just as helpless in the face of over-running engineering as the train operators. They should have to be convinced that IP’s plans are robust and capable of being delivered before work takes place. And IP’s arguments must be more convincing than simply applying an average to previous work and then saying that this means future work will not be late.

Each RMD could drive major improvements across NR by simply trying to do better than their counterpart on the next route. They could also do better if they had more local resources, to make the best use of the capacity of their routes. While government talks of local power and accountability, NR has created a centralised railway run from Milton Keynes. It is nowhere near as devolved as many people think.

It’s also NR’s IP division that sits behind the series of delays occurring on many upgrade projects, such as the electrification of the Great Western Main Line (late and with costs far higher than originally suggested) and the electrification of the trans-Pennine route through Huddersfield (late and now with no completion date). A similar project for the Midland Main Line was required by government to have been completed in the current 2014-2019 Control Period, but has slipped into 2020.

Analysis of recent NR enhancement programme updates reveals that a lack of resources is at the heart of many of these delays. This is not just NR’s fault - the Government asked for more than the railway could deliver, showing that it was not an informed customer.

Analysis of recent NR enhancement programme updates reveals that a lack of resources is at the heart of many of these delays. This is not just NR’s fault - the Government asked for more than the railway could deliver, showing that it was not an informed customer.

DfT appears to have no overall strategy for the railway and has instead chased the headlines that come from announcing major projects. It doesn’t help that the price tags DfT initially attaches to these projects are subsequently exposed as woeful underestimates. This puts them and the railway on their back foot in terms of public perception and means that ministers cannot deliver what they’ve promised.

Regulator the Office of Rail and Road cannot escape censure either. ORR has the role of checking that government’s plans can be delivered for the money government is offering. It commissioned numerous reports into many aspects of NR’s work in the run-up to the current Control Period, but in accepting government’s overall demands it appears equally naive about the industry’s ability to deliver.

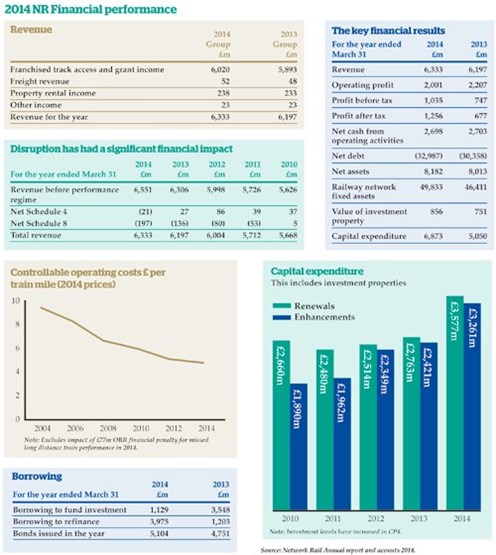

If IP is divorced from the passenger-facing realities of running a railway, it can be argued that NR itself faces more towards its owner (the Government) than its customers (the train operators). It’s not only the call that the Transport Secretary has on NR’s chairman, but also from what Apprentice star Nick Hewer accurately identified as “following the money” in his recent BBC2 rail documentary. Do this and the road leads to government, with NR receiving £3.6 billion from it in 2013/14. This compares with the £2.1bn it received in charges from its customers, the train operators.

If diagnosing the problem that NR is aligned more to government than to its customers is simple, finding an answer is considerably harder, if not impossible.

Ideally, NR should receive its income from train operators, including freight and open access companies - they are the ones that use its services. But hiding behind the large sums of money that flow round the industry is a huge amount of enhancement work. Government support in building a better railway is welcome, and it’s right that taxpayers contribute because the country should benefit overall from a better railway. But this increased spending has disguised the good work NR has done in reducing day-to-day costs by becoming more efficient and doing more with less.

Feeding this improvement money to NR via the TOCs exposes a tension between the short-term nature of the operators and the long life of improved infrastructure. The massively improved Reading station and its radically remodelled approaches will last considerably longer than its main user, First Great Western.

Passing money through the TOCs would likely put many that today pay government a premium into subsidy, with little likelihood that the real reasons will be understood in a ‘sound bite’ debate surrounding subsidies and profits. It would only serve to complicate an already confused picture.

Line upgrades

Yet it’s surely sensible that train operators are exposed to the costs of (and the decisions surrounding) the infrastructure they use. In the public sector, Transport for London operates the capital’s Underground system in a vertically integrated fashion with its hands on track and trains, and it has delivered successful line upgrades involving both sides of the wheel-rail interface.

There is now more capacity on the Victoria Line, while the Northern and Jubilee Lines have also been improved. New trains run on its sub-surface lines, even though TfL and London Underground have run into severe difficulties in upgrading aged signalling on those lines, and have now ditched two contractors.

The signalling problems surfacing on LU are also evident on NR. With major projects to shift control of trains from hundreds of signal boxes to a handful of Route Operating Centres (ROCs), NR has a tidal wave of work approaching. And that’s before any thought is given to Chief Executive Mark Carne’s hobby horse, the ‘Digital Railway’ - progressively rolling out cab-based signalling nationally that does not yet exist.

Both the ROC programme and the Digital Railway hold the prospect of considerably reduced operating costs, which should make the railway more efficient. However, these efficiencies are set to disappear if implementation costs soar as a result of the programmes overheating their supply chains.

In addition, delaying signalling projects can have an impact on associated plans such as electrification or track remodelling schemes. Delays can also result in extra money being spent to keep existing signalling going. This is a particular problem with installations dating from the 1960s and 1970s, where obsolescent and ageing wiring are becoming concerns.

Over in the US, the big freight railroads are private companies but are vertically integrated and successful. (The US also has increasing problems with lack of infrastructure funding, as was brought home in May’s derailment near Philadelphia.) Japan has private rail companies that run tracks and trains on a regional basis. In Europe, French and German state railways stubbornly resist separating the two, despite European Union directives imposing such a split in accounting purposes.

Meanwhile, Britain has split the two in both the private (Railtrack) and public (NR) sectors. One failed, and the other stands in similar danger. This line of argument points towards vertical integration as the way forward, despite EU strictures. And recent moves towards alliances between NR and train operators suggest high-level acceptance of this integration argument, while retaining a facade of separation.

The alliance model is at its most developed on the former South Western Division of BR. Trains are now run by Stagecoach operator South West Trains, whose managing director Tim Shoveller is also responsible for NR staff on his patch. Created in 2012, it has not improved performance as quickly as anticipated, although Shoveller is convincing when he argues that its problems run deeper than originally thought and that the service would be much worse were it not for his alliance.

The SW Alliance is public-private hybrid, but forms a good model for an outright regional privatisation of a vertically integrated company - or at least it did until, according to NR in mid June, Stagecoach pulled out of the joint financial arrangements, ending the ‘deep alliance’ experiment. Notwithstanding this sudden setback, government could package and sell a part of NR to own the SW tracks and infrastructure, and could sell its franchise rights in perpetuity. There would still be a need for ORR regulation, because other companies would use the tracks that owned by the new (private) South West Rail company.

There are difficulties in this approach, however. It’s not clear how government would seek to replace the income that it receives from the premium paid by today’s SWT. Nor is it clear whether the new private company would be sufficiently large to cope with major enhancement projects that might become necessary. Could it cope with a £1bn project to do to Clapham Junction what NR has done to Reading, for example? Could it cope with replacing DC electrification with more efficient AC overhead wires?

Perhaps, if the SW model was expanded to include the former South Central and South Eastern divisions, to create a company based on southeast England’s DC network. It’s possible that the premium goes into enhancements directly, rather than being sent to government only to be returned as infrastructure body funding.

Raising private sector money is more expensive than using government funds, but it might well be that the private sector would be more disciplined than governments in deciding what is needed - and then sticking to it, preventing scope creep and delivering a project more efficiently. Those who remember the private sector’s performance in LU’s public-private partnership might disagree with this statement, however.

Vertical integration

Scotland provides another vertical integration project. Here, government agency Transport Scotland provides the money and direction for Network Rail and specifies the train service to be run by ScotRail. The latter is privately delivered (ironically by Dutch state railways), but it’s easy to see the politicians of the current Scottish government wanting it publicly run, if UK law permitted this.

Some routes do not easily lend themselves to vertical integration, either public or private. The East Coast Main Line is one such route, because of the number of current and prospective open access operators in addition to the franchised inter-city operator. Privatisation might work if the track owner was sold and the franchise sold as a private company with a package of access rights. It would then be for the track owner to decide which trains ran, without the spectre of government providing its money and specifying the main operator’s services.

There are also services that do not fit well in regional models. At privatisation, Central Trains took on a mish-mash of services around the Midlands that did not dovetail with any other operation. Central has since disappeared with its services transferred to other franchises where they fit equally badly. So East Midlands Trains runs between Liverpool and Norwich, barely touching its core London-Sheffield line. And CrossCountry runs Birmingham-Stansted Airport with 100mph DMUs wending their way towards East Anglia, in a far cry from the inter-city operation XC was created as at privatisation.

This regional approach makes for a complex railway with some parts public and others private, some vertically integrated and some still with a track-train split in place. It could absorb significant management horsepower just at a time when those efforts could be better spent delivering today’s upgrade programme.

Outright sales are not the only form of privatisation recently seen on UK railways. In 2010, the Government sold a 30-year concession to operate High Speed 1 (the international line from St Pancras to the Channel Tunnel). Government remains the owner, and expects the line to be returned in 2040 in the same condition as at the start of the concession. This leaves operation, maintenance and renewals in the hands of the concessionaire.

The key difference, however, is that as a newly-built railway, HS1 was transferred in a known condition, and is not expected to need enhancing in the next 30 years. The same cannot be said for domestic UK lines, although with long-term deals, a concession could provide the means to fund enhancements.

It’s a model that could have been applied to Chiltern Railways and its line from London Marylebone to Birmingham Moor Street. This route was subject to a total modernisation of track, signalling and trains under British Rail in the early 1990s.

Train services switched to the private sector in 1996, and the operator secured a unique 20-year deal in 2002. This has enabled it to embark on a phased upgrade programme to improve track capacity and station capacity and it’s now laying a new line at Bicester to allow trains to serve Oxford. Funding for the latest work is coming from Network Rail, with Chiltern and subsequent franchisees reimbursing it over 30 years.

Relatively self-contained, a concession could work… subject to agreement about how improvements that outlast the concession itself are treated when the deal expires.

Should government decide that it wishes to continue following EU directives and keep tracks and trains financially separate, it could simply return Network Rail to the private sector with an outright sale. What price ministers might receive for a company with debts of over £30bn is open to question, although they would most likely have removed those debts from their books before any sale. They might even look to sweeten the deal by writing off some of those debts.

It could privatise the company on a regional basis, with the national company’s debts then split either on an arbitrary track mileage basis or (perhaps more fairly) on the basis of the proportion of recent enhancement work that triggered the debts.

But whatever the financial complications of such a sell-off, it’s unlikely to remove the railways from the political sphere. Ministers will still be fielding questions about rail performance. If events go badly, they will be blamed because they sold the company. And if events go the same way for the public sector NR, they will still be blamed. Essentially, selling NR only achieves the effect of taking its debts off the Government’s books (and they were only put there by changes to EU accounting rules).

It doesn’t appear worth the Government’s while to go through what is bound to be a politically complex problem of privatisation, let alone the problems of regional splits of debts or funding. It would take a brave minister to push through such a programme.

The gorilla in the room

From the railway’s perspective, NR (whether public or private) will remain the gorilla in the room, able to sit exactly where it pleases if it remains a national company rather than being split. It could still dominate the train operators and still pay more attention to its shareholders than its customers.

Privatisation does not appear to be the obvious answer to the problem of NR’s failing enhancement programme. So if ‘something must be done’, what that something is in the long term currently remains the key unanswered question.

In the short term, NR and DfT must rigorously examine that failing programme. It’s running out of control and is taking NR’s costs with it. NR has tried to tame it by postponing work, but it’s now time for a complete examination because postponement just delays the inevitable implosion.

DfT must look at what it asked of the railway in its 2012 High Level Output Specification. It must decide which of its demands remain feasible and which remain important, and must cut from the programme that which satisfies neither criteria.

What is clear is that the railway cannot carry on regardless. It is accumulating problems, and if nothing is done those problems will bite hard. Passengers have been promised improvements and they have been told that fare rises are paying for them.

If the railway and the Government cannot deliver, then they must be open and honest - explain the problem and explain their proposed answer. It might be painful… it might be embarrassing… but it must be done.

Peer review: Len Porter

Peer review: Len Porter

Asset Management Consultant and former Chief Executive, RSSB

This is a timely article, because one senses that the way the industry is currently organised and structured must evolve and change, not least because we have a new government that will be thinking about what is required to deliver a more sustainable long-term future for our railway and its finances.

Much has been written over the past decade or so about the industry’s lack of strategic long-term thinking, and its inability to plan and project-manage cost-effectively. Government and the Office of Rail Regulation (now Rail and Road) bear some responsibility, however, because they have been less than consistently helpful. his is a timely article, because one senses that the way the industry is currently organised and structured must evolve and change, not least because we have a new government that will be thinking about what is required to deliver a more sustainable long-term future for our railway and its finances.

There are various examples that one could give to illustrate this, but delivering a High Level Output Specification that dropped electrification and high-speed rail, only to put them both back in again a few years later following mounting criticism, clearly illustrates this inconsistency. For similar reasons, it has been difficult to estimate costs on larger complex projects and Network Rail, DfT and ORR have never really got this quite right. I do have sympathy with their problem, however, because improving a Victorian railway can throw up significant problems that may have been difficult to foresee before renewal or enhancement work starts.

Cost escalation as a result of poor planning isn’t good, but perhaps more damaging in the longer term is the impact on the supply chain and skills availability. We have certainly caused harm in this respect, owing to the feast and famine approach to the way asset renewal programmes have been planned - be they rolling stock or infrastructure. The current troubled electrification programme is a rather disappointing but very clear example.

Railtrack contracting out maintenance should not have been the problem it proved to be, since this outsourcing has been successful in other safety-critical industries. Not retaining a critical mass of in-house competence, introducing relevant due process and systems was, however, a major error.

Even after bringing maintenance back in-house at Network Rail, leaving the data, information systems and fragmented asset knowledge in the hands of the contracting community lost Network Rail a lot of time in implementing modern asset management practice. Nor was this helped by NR’s procurement practices, which were (for a considerable period) largely those of a bygone and much more adversarial era.

Furthermore, if you incentivise an executive team to take cost out rather than ensure that key systems and due process are in place, the problem is compounded. It is easy to do the former without the latter, but difficult (although essential) to do both at the same time. The way this is being implemented at both Crossrail and HS2, following the BIM (building information modelling) approach, are certainly good examples of the way forward.

All that said, let’s not be overly critical. In my experience, our rail industry is really rather good. In my opinion, it’s better than most in Europe and on all other continents. It has some of the best people, but structural fragmentation has led to difficulty in bringing together a critical mass of capability - whether that be in leadership, engineering, technical or operational skills. Pulling critical mass together through the various discipline leadership sub-groups has worked to a degree, but there are too many of these. Introducing the Rail Delivery Group, although well intentioned, doesn’t seem to have actually solved very much.

The rail sector’s best people are in all parts of the industry - Network Rail, passenger and freight TOCs, ROSCOs and the supply community, including both large companies and SMEs. They are not always in the bigger players, however, and may not be at CEO or even board level. The biggest, best-funded and resourced player is Network Rail, and it is hard to ignore the fact that getting NR to work effectively and efficiently would solve a lot of the industry’s perceived problems. Those working at all levels in Network Rail have difficult jobs, and much is expected of them. Philip Haigh’s article examines ways of rearranging leadership responsibility, but it’s not easy and certainly should not be made more complicated.

I would suggest that now is the time to think longer term as to what rail will need to deliver in an integrated transport sector of the future. In an age of electrically driven potentially driverless road vehicles, capable of being assembled into road trains, the railway needs to think very carefully about its role in this new world. And there is absolutely no time to waste - driverless technology for road vehicles already exists.

So an integrated transport policy with associated land use and energy policies is going to be an important consideration. In my view, Network Rail, Highways England and the Scottish equivalent should be sharing some kind of joint vision of the future - not trying to protect either road or rail, but maximising each for the benefit of the other, and bearing in mind that they may both be drawing heavily on an overstretched energy supply. Interestingly, both rail and road often draw heavily on the same supply base, and that may become more critical in the future. In my view, this is both an opportunity and a threat to GB transport plc - approached properly, I’d prefer to think of it as more of an opportunity.

The rail sector will need to work much more collaboratively in the future than it has done in the past. Contracts will need to be more of a deep partnering nature and involve all parts of the industry, including the supply chain. The TOC/NR axis is but one part. Integrated transport or rail projects are much more about multi-party relationships, technology and innovation, driving improved performance at reduced cost and with a careful eye on business risk. of which safety risk is but a part. It will need enlightened procurement relationships with GB transport plc to bring this about.

When it comes to making progress in this respect, I’m more inclined towards corporate bodies than committees, and at the heart of all this going forward is leading-edge modern infrastructure asset management. This is much better understood nowadays, with some fine documents and examples to draw on. You could argue that it is just value-driven smarter business management, and I would agree with that, but the documents leading up to and including ISO 55000 provide a good foundation.

As for organisation, I am a big fan of keeping it simple. What are our objectives? What is it that we want to deliver? I would start by getting some of the industry’s best people around a table (bearing in mind my comments earlier about leadership) to thrash this out. Then look at how to organise to deliver against that. Structure and people to populate the structure follow on from there, including at board level.

Network Rail is likely to be a key player in this exercise, which I believe would benefit them and the rest of the industry. TOCs are important, but when it comes to longer-term integrated transport, engineering, technology, project and asset management thinking, there are others (interestingly, the historically longer-term players) who are likely to be just as important in this debate. Done properly, this could reduce the dependency on our committee culture, in favour of a more inclusive corporate entity with the critical leadership mass to drive us positively towards a better future.

Peer review: Libor Lochman

Peer review: Libor Lochman

Executive Director, Community of European Railway and Infrastructure Companies

Denmark and the Netherlands, both with separated state-owned infrastructure managers, experienced rail freight market share increase of around 60% and 50% respectively between 2002 and 2012. Austria and Italy, both with vertically integrated infrastructure managers, experienced rail freight market share increase by over 40% over the same period.

On the other hand, the Czech Republic, Spain, Romania, France, Slovakia and Bulgaria (separated infrastructure managers) suffered a decrease in their rail freight market share. The rail freight markets of Lithuania, Estonia and Slovenia (integrated infrastructure managers) did not perform well either.

All this serves to illustrate that rail reform in Europe has gone in all directions, despite the increasingly narrow range of possibilities offered by the EU legal framework. Good and bad results have come from different policy approaches - it seems the secret for success lies a little bit beyond choices on governance and ownership. Infrastructure investment enhancing the quality and capacity of the rail network and compliance with harmonised technical specifications are both good choices, as is avoiding geographical fragmentation of management.

The European Commission has been promoting the corridor concept for rail infrastructure operation, upgrading, maintenance and development for years, and this should probably be included in the list of good ideas stemming from the Union’s executive branch. Any sub-national fragmentation should be prevented, since it could re-create at national level those problems we already see at European level, where the said ‘corridor approach’ is often accepted in principle, but in practice often struggles against national priorities.

Also key for any reform of the rail system is co-ordination between rail operations and infrastructure management. Experience shows that vertical integration can be a way for the infrastructure manager to keep a link to market needs via its sister rail operating company. In Member States where the state-owned infrastructure manager is separated, such a link can be emulated by a sound business culture cultivated by the public sector, and by a strong call for efficiency from the public shareholder.

Finally, speaking of efficiency, it is important to incentivise infrastructure managers to run efficiently. But the question is not how to keep customers and shareholders happy at the same time, as if this were a trade-off of some sort. Indeed, it is not only the customers who request efficiency, but also the public shareholder, who in principle should have electoral incentives to request efficiency on their behalf.

If we want to get to the heart of the issue, a lot more should be investigated in this field, beginning with the place that transport policy occupies on the parties’ agendas and the overall quality of EU democracies. Maybe rail scholars should spend more time investigating how transport and rail policies score on the list of hottest topics for political agendas in electoral years. Making transport a political issue could contribute to a better policy – that could be the incentive we need.

Peer review: Nigel Harris

Peer review: Nigel Harris

Managing Editor & Events Director, RAIL and RailReview

Philip Haigh is a seasoned and experienced observer of the post-1993 privatised railway and he has neatly and effectively summarised the fundamental problems and key questions surrounding Network Rail’s structure, role and challenges. The picture he paints is as profoundly depressing as it is worrying.

What makes the NR conundrum so multi-faceted is that despite the very obvious problems of infrastructure efficiency, lateness and overspend, I still believe we have the best railway we have ever had. A doubling of passenger figures from the BR legacy of 800 million a year to today’s 1.6 billion is as much about a better-quality privatised product as it is a reflection of a growing economy.

The post-2008 recession proved that the old link between GDP and rail use had been broken - rail growth barely faltered despite the worst global recession in living memory. Trains are a great idea whose time has come again - but the way we manage infrastructure, while delivering that excellent railway, is still too expensive and too inefficient. And the NR conundrum lies at the heart of that sweet and sour outcome.

Rail infrastructure is just too expensive for the private sector to provide and maintain and in any case good rail services are fundamental to national economic success and so it is right that the state plays the core role in providing it. Hence I have no problem with NR being nationalised. What I do have a problem with is the costly clutter and waste surrounding it, a legacy of what was necessary to underpin the fiction of a privatised status under which NR has laboured since birth. So let’s get rid of the pointless members and take a good look at ORR while we’re at it. The regulatory function performed in other fully privatised industries is an illusion in rail, and any fines imposed on today’s clearly nationalised infrastructure owner would be ludicrous. But you can’t effectively sort ORR until you decide what to do with NR!

The DfT might decide to take devolution to its limit and set up half a dozen independent NR regional entities, in which case ORR could have a major role in ensuring consistent standards and efficiencies, driven by inter-regional ‘competition’ and benchmarking. Maybe ORR could also have a role in ensuring retention of the benefits of scale in procurement.

But before DfT makes such seismic decisions it needs to figure

how much of this problem is structural and how much of it is just

crass management and incompetence? For example, the King’s

Cross christmas overrun flowed from problems including a contractor who thought it was acceptable to bring untried equipment onto a very sensitive possession. This was made worse by NR managers then.keeping ‘schtum’ for far too long about the scale of the problem. None of this is structural - it was all incompetence.

So is the NR problem about structure or expertise? How much of an issue is the perceived lack of enough rail and asset management expertise at the top of NR? Should we give Chief Executive Mark Carne and Managing Director of Network Operations Phil Hufton a beefed-up top team of proven calibre? This would be eminently possible very quickly and could yield some quick and positive results. I’d happily provide a list of suitable names, if required.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.