Read the peer review for this feature.

Read the peer review for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

For all the screaming headlines last Christmas about Network Rail’s engineering meltdown at King’s Cross and Paddington, the subsequent delays to services are expected to have no effect on the Moving Annual Average punctuality for train operators East Coast and First Great Western.

In total, just three possessions overran at Christmas out of the 800 implemented by NR’s Infrastructure Projects division. One of them was by just an hour, while the other two were the pair that captured the headlines.

They did so because of the disruption they caused to many thousands of passengers. Chaotic scenes caught on camera at Finsbury Park station in north London did not paint rail in a good light. Those passengers were not the commuters that are Finsbury Park’s staple. They were “families with young children, the elderly and vulnerable often travelling with lots of luggage in an unfamiliar environment”, according to the Office of Rail Regulation.

Were the problems at King’s Cross and Paddington typical of NR’s engineering programme, or were they simply eye-catching outliers of a normal pattern of work?

There’s no doubt they were serious problems. Were they not, then NR Chief Executive Mark Carne would not have made this opening comment to the Transport Select Committee on January 14: “Let me start off by once again unreservedly apologising to all the travelling public on December 27 who were affected by the two incidents at King’s Cross and at Paddington. Clearly this was an unacceptable situation for them and they had a very difficult day.”

This was not the first time NR’s Christmas work has delayed thousands of passengers. Back in 2007, trouble at Rugby crippled West Coast Main Line services. It led to major changes in the way NR plans engineering work, with a new process introduced called Delivering Work Within Possessions (DWWP).

Risk assessment

DWWP introduced a risk assessment - called a Quantified Schedule Risk Assessment (QSRA) - that sought to refine plans such that they had at least a 90% chance of running to time. For Christmas line closures, NR looks for an even higher chance (95%).

Francis Paonessa is the man charged with delivering NR’s renewals and improvement work, as its infrastructure projects managing director.

“You don’t need to be a mathematical genius to figure out that if your risk analysis says you’re going to have a 95% chance of handing back on time, then 1-in-20 probably won’t. Or won’t unless there’s additional intervention or time or something. So that’s not to say that when we enter a weekend planning that 1-in-20 jobs will overrun, but of those critical ones, unless some intervention is put in place, that would be the statistical likelihood based on the Monte Carlo analysis that we’ve done on those projects.”

Increasing the likelihood of an on-time handback from 90% to 95% or to 99% comes at a price. The project management team can put in more resources, such as spare equipment or personnel, but there are times when neither is available. The other option is to look at reducing the impact of any overrun - that is, have a contingency plan for running the railway in some other way if a stretch of line remains closed for longer than expected.

QSRA works by taking a project, splitting it into component parts, and then looking at the likely minimum and maximum times each part could take. It then runs scenarios based on all the parts taking their minimum time and all the parts taking their maximum time, and from there works out the distribution of the likelihood of when the job will finish. For jobs made of standard parts, the result should be fairly accurate. For jobs with novel elements, it’s much more of a challenge to work out the range of likely times.

ORR criticised the QSRA for King’s Cross, noting that meetings had been badly attended. But, counters Paonessa, it was a standard job - having more people at the meeting would not have changed the outcome.

However, he adds: “What we are doing now - putting that extra level of discrimination in between the things that are made up of standard elements, which most of the track jobs are, and the things that are made up of things which have a uniqueness to them, where actually figuring out what the maximums and minimums are is that much more difficult - is why having a greater representation actually at the meeting makes a bigger difference.

“It was a good reminder that on the unusual jobs we need a broad attendance, but actually on the standard jobs of a more repetitive type it’s less critical. But it has really made us look again at it, to ask if there’s a better way of doing this.”

Paonessa acknowledges that QSRA doesn’t explicitly cover each individual element of a job. It doesn’t, for example, appear to cater for the four brand new log grabs used at King’s Cross which had been provided specifically to reduce the risk of delays, but which NR’s report admitted leaked hydraulic fluid.

The risks of specific resources within a project affecting its outcome appear to be averaged out in the statistics loaded into the QSRA process. It’s rather like the delays to the thousands of Christmas passengers having no overall impact on the year’s punctuality figures.

Paonessa takes up a wider project management thread: “Now the other element is that the process overall just can’t cater for every single incident. You can’t continge for everything. So where we have a big Kirow crane - yes, we’re going to have fitters on site and, yes, we’re going to have people who can do running repairs. But if we have a catastrophic failure of a Kirow there is no contingency plan, because we can’t put two spare cranes on site when we only have three in the country.

“There are some that we just can’t mitigate for. But what we’re now doing, since Christmas, is having another look back at that overall integrated process and saying that if you put the passenger at the heart of that, how do we minimise the disruption to passengers. We either do that from having a fantastic operational recovery plan, if it is possible to do that, or we have to put additional layers of contingency into the project plans. All of which on the project side can cost money… and a considerable amount of money.

“We had a very good example at Wimbledon just after Christmas. We had a planned blockade of five weekends to replace the six sets of S&Cs at Wimbledon, which have sat there since the 1980s and are in quite poor condition with wooden sleepers. It causes lots of operational issues for South West Trains, so it’s a highly critical job.

“The dilemma with Wimbledon, and the reason it’s been deferred so many times, is that it’s difficult to access Wimbledon. If you have a problem at Wimbledon, you not only block Waterloo, you trap SWT trains in the depot.

Schedule risk analysis

“There really is no operational contingency plan that can cope with blocking Wimbledon, so we had another look at the Schedule Risk Analysis for the job and said well, we’re planning to do two point ends, one point end, two point ends, one point end and some follow-up work, but we can actually only safely do one point end (actually, it’s two points - one crossing) per weekend. That adds 30% to the cost.

“So when I say there are real costs in raising the probability of handback from P90 to P95 to P99, they are real and they are quite significant. So we are working on a more sophisticated process that can balance that triangle of the passenger TOC, the operational contingency plan and the project contingency plan, with the costs sitting somewhere in the middle of that.”

Probability runs solidly through project management. What are the chances of all tasks being completed correctly and on time? And, if not, how long will it take to find and correct any errors? For example, in the 5,000-plus words of this article you should (hopefully) find no spelling or typographical errors. You can be pretty certain that the first draft had some of both, which were all later found and corrected.

So it was with Paddington. Critical to this job was checking the changes made to signalling as a result of the changes made to track layouts. Only once all these changes had been made, checked, corrected as required and then checked again could the railway re-open. There were, says Paonessa, something like 10,000 checks to be made.

Under a series of testers-in-charge at Paddington, checks were made and defects reported. Paonessa recounts what was happening:

“Those defects are being loaded into the forward work bank. You’re munching your way through a process that gets you to a point, when you’ve finished, where there’s an hour’s worth of shuffling a stack of paper. And the stack of paper fills three A4 lever arch files - it’s not a simple piece of paper with one tick on it.

“But when you get into those last two hours, if in pulling it all together you find that you have additional work that you need to do, or work that you haven’t completed and you need to go back out and do that, then you need a heck of a lot more time than shuffling the stack together and putting the final tick on it.”

He continues: “So we got to the end of the process - we thought we’d got to the end - and at 0330 the tester-in-charge thought they had an hour’s worth of snagging together. But in going through and carrying out that final detailed check, they found there were some additional things that needed to be done. We had to send people back out onto the railway, so we had to take some possessions.

“As it turned out, we had deferred some overhead line work which wasn’t critical to the handback. We’d deferred that, and since we thought we’d finished testing we put a whole load more MEWPs (Mobile Elevated Work Platforms) back out to do some of that overhead line work. We’d now deployed MEWPs in the area, but we needed to do some wheels-free testing, so we had to get them back off the line as well.

“There were lots of things that stacked up into this process, all of which was around finding testing that was either incomplete or needed to be redone to satisfy the tester-in-charge that what he was handing back was safe to do so.

“Quite a long complex story in all of that, which ends up in a huge amount of detail that doesn’t really help the travelling passenger much at the end of the day. We thought we’d got there and then we found we weren’t. And, of course, we found we weren’t just at the point we were supposed to be handing back.

“That’s what caused such significant difficulties in coming up with an operational contingency plan. We gave the train operators no notice, so we had a fair bit of criticism for First Great Western drivers sitting at signals thinking they were going to be 30 minutes because our best view at that time was that it was going to be 30 minutes.

“It’s a very, very difficult balance when the whole safety of the railway and that whole process is sitting with one individual, and they’re saying it’s going to take 30 minutes. At what point do you stop them and spend an hour trying to understand exactly where we are? Because that’s an hour lost. Or do you leave them with it and let them finish? That’s a really difficult balance to make.

“The team on the ground figured that at 0830 that was the time we needed to stop, draw stumps, and have a long hard think about exactly where are we with the knowledge that we had.”

It must be said that the complexity at Paddington - the 10,000 checks - is hardly unique. Other projects have similar challenges yet are delivered on time. With some pushing, Paonessa concedes that it was “the volume of time that we had to start with and the volume of work that we had to do”.

He adds: “The stack-up of bits that went in there. To be perfectly honest, the process didn’t work as effectively as it could have done because we ended up with a situation at the end where the tester-in-charge thought the work was done, and when we did that final evaluation we found that it wasn’t. There is absolutely a piece in there about the management process that sits around the management of that scope of work.”

Compromise at King's Cross

That balance between volume of work and time available is a theme that runs through Paonessa’s interview. NR wanted four days of full closure for its King’s Cross renewals job - it ended up with two days of complete closure and two days of partial closure. With the West Coast Main Line also closed, a full four days was not available. NR had said after 2007’s problems that it would not have both Anglo-Scottish routes closed at the same time. The clear message from Paonessa is that meeting this requirement compromised NR’s chance of completing its King’s Cross work.

“I think I’d say a couple of things. One is that I think Network Rail and the train operators, and the freight operators, do a great job on a daily basis in minimising the impact of quite a large number of incidents that happen on the railway that are not of our control or of our making.

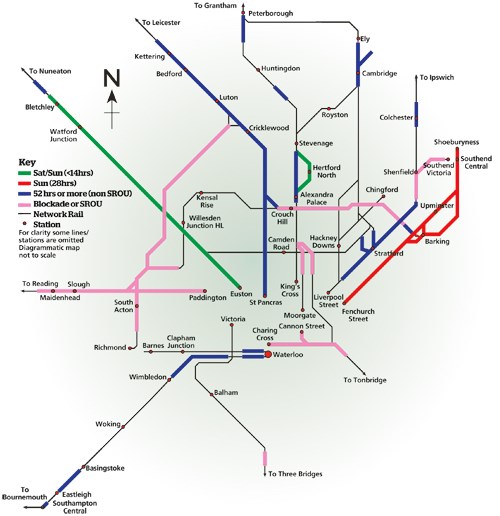

“Christmas and the Bank Holiday periods really complicate that because we have so many areas where we are working. We had 2,000 worksites just as infrastructure projects at Christmas, across 800 possessions. Every single one of those is affecting the railway.

“I think the key part that came out of the report was yes, we look at operational plans and yes, we look at project delivery plans, but our focus is to remember why we have those two and to set ourselves at the top as the passenger, and say: OK, we’ve got this plan and we’ve got that plan, how do they add up to make sure that we minimise disruption to a passenger either through a great plan or a great project delivery plan that has great certainty of delivering.

“Recognising that with the Wimbledon discussion - the more certainty you want of the delivery plan, the more it will cost. And the travelling public wants and quite rightly demands that the railway costs less to operate. So we end up with much tighter boundaries and much tighter constraints, and people have higher expectations. You can’t fault that, but it is a much more difficult circle to square every single weekend.”

NR has long tried to squeeze major engineering work into holiday periods such as Christmas, Easter and Bank Holidays, when fewer commuters will be affected. It also provides the opportunity for longer closures.

ORR’s investigation into the Christmas problems exposed one of the difficulties with the broad assumption that fewer people travel. The days of most disruption were Saturday December 27 and Sunday December 28. For First Great Western, its overall numbers were down - 158,000 passengers over December 27-28 compared with an average weekend of 242,000. But East Coast had more passengers than it would normally expect on a weekend - 84,000 compared with 76,000. (FGW had more delayed passengers, but news coverage focused on Finsbury Park/King’s Cross, probably because there was warning of this overrun.)

The best time to close a line

Even if the broad assumption of fewer travellers is more generally correct than it was at Christmas, it’s fair to say that weekend and holiday passengers will have more bags and be less experienced than the everyday commuters who so skew overall passenger figures. In other words, the railway may find it easier to re-route regular commuters for a period because they will learn a new (if only temporary) routine in a way a heavily loaded occasional traveller will not.

The subject on when is the best time to close a line for engineering works is currently under review by the Rail Delivery Group.

“That’s quite a complex question because part of it is around our ability to deliver that work. Clearly, sticking everything into a short period of time a couple of times a year stretches the resources and makes things very much more difficult,” argues Paonessa.

“For example, take the train driver issue. On a normal weekend, when we start running out of train drivers we can usually rustle some up. Frankly, on Christmas Day, you’ve got the train drivers you’ve got - the others are at home with their families, so it makes it that much more difficult because there are that many more constraints.

“If we’re doing all these big activities at certain points in time, there are only so many tilting wagons and there are only so many big Kirow cranes. Buying a whole load more of those is very inefficient, because they’re standing for the rest of the year. So if there’s a piece of work looking at how we can better balance that work out, that’s great.

“I think the other piece which is equally important, and which was quite key at King’s Cross, is that the time of year drives the type of passenger that we have, so that adds a layer of complexity. It also puts the train operators in a difficult position - what do they do to enable us to have longer periods of time in which we can provide a greater level of surety.”

NR is also forced into very long planning lead-times for scarcer resources. Paonessa explains: “At T-8 , it’s a bit late to wake up and say I don’t have enough, which is why we run the process so far in advance. We already have a very clear view of what Christmas 2015 will look like - and it’s full.

“We also know what Easter 2016 will look like, and we have a very good view at the moment of what Christmas 2016 will look like. We’re already matching our plans to make things fit.

“But some of these big activities at Great Western, for example, have so many sequential large activities that can only fit in at one point in time. So our programmes are driven by when Christmas and Easter is, not by what’s best for the programme or is most efficient.

“If we had opportunities to spread that workload out it would have multiple benefits to us as the people doing the work. If I sit with my Network Rail infrastructure projects hat on, I’d love lots of long weekends.

“The flip side of that for the train operators, who are clearly there to serve the travelling passenger, is that it’s very much more difficult in that they have a different set of priorities and a different set of drivers. Ultimately the railway is here to move people around, it’s not here to build bridges and lay track and resignal stuff for its own sake. It’s quite a difficult question, and I’d be very interested to see what the report comes back with.”

So if that’s the story of Christmas, where does it leave Network Rail with its five-year work programme that is just coming to the end of its first year. For renewals alone NR is funded to £12 billion, with track and signalling consuming just over £3bn each and civil engineering around £2.4bn. That brings a considerable amount of work - for example, about 800 miles of conventional plain line rail renewals and about 470 miles of high-output rail and sleeper renewals.

The bill for enhancements is a similar £12bn, with eye-catching electrification projects under way for the Great Western and Midland Main Lines, and Edinburgh-Glasgow. There are also the Northern Hub and East West Rail projects to progress, plus numerous smaller regional schemes.

On top of this, there is Reading and Thameslink to complete, while NR is also playing a key role upgrading suburban lines east and west of London for Crossrail. That project itself will soon move from its Central London tunnelling phase to fitting out, which will demand more railway resources.

And then there’s High Speed 2, which should shift from its planning phase to more detailed railway design work over the next few years. All this, plus London Underground’s continuing modernisation programme, will consume resources. Which begs the question: is there enough to go round?

Paonessa initially appears relaxed, saying: “There’s a broad discussion at actually quite a high level. We have a people steering committee between the three organisations (Network Rail, Crossrail and HS2), which is attended by our respective group HR directors. They get together and look at that national resourcing issue. Different phases of different projects demand different types of resources. We certainly see that at the moment. We have the tools to look at those resource demands and we’re working our way through it.

“Of course, the vast bulk of Crossrail’s surface railway is being done by Network Rail in any case. We’re well on with activities both on the west and east of Crossrail, and doing a really good job. High Speed 2 is in a slightly different phase, but certainly raises all sorts of questions of that smoothing of projects as we move into the back end of CP5 and into CP6.”

Resources needed

To the suggestion that this makes it sound as if there’s not much of a problem, he expands: “I think it really depends on what fits in where, and what are the major schemes that are also potentially happening in the railway at the same time.

“We don’t know what will happen in any spending review. We haven’t even started our submission for CP6. Will investment in rail continue at the current rate? How will that be split across the major projects? There are a lot of unanswered questions.

“But certainly for the next couple of years we have a very clear view of the resources we need. And while it’s certainly demanding of the industry, we are also more open-minded about bringing people in from all sorts of other industries. As our sector is growing significantly, others are not in such a fortunate position. We’ve brought in a lot of people from the armed forces - very, very skilled people who come in with a great approach and a great work ethic who are very well trained. That’s been very good.

“Equally, people running large projects in defence, who again come in with a whole set of very complementary skills - myself included. I’ve spent most of my life in defence, and then moved into rail really through the major projects route through Bombardier to then come to Network Rail. It’s a really complementary set of skills. If there’s one thing that defence companies do, it’s that they run large projects that are the ultimate in low-volume manufacturing - huge projects that deliver maybe one big thing or a few slightly smaller things.

“We’re looking at UK industry as a whole, and bringing in the sort of resources that we think we need to deliver that. But what I would say is that it is a challenge. We’re delighted to have the investment in rail that we’ve seen.”

The uncertainty in future work beyond the next few years is particularly acute for signalling contractors - such as Signalling Solutions Ltd, the company responsible for Paddington’s work at Christmas. Paddington was also its second major overrun of 2014, the first having been at Poole in May. Having looked into the problems at both jobs, Paonessa and his team have concluded that they should proceed with a further job at West Slough this Easter.

Whether or not NR has sufficient signalling contractors for the work planned overall is open to question, and indeed is being questioned within NR itself. Paonessa explains: “It’s difficult. We ran a competition a few years ago to appoint our three framework contractors that do our signalling. They are by no means the only ones that can do signalling work for us, but they carry out the vast majority of the major signalling schemes that we have.

“There are some advantages in having more, and there are disadvantages in having more. Three is the number we have at the moment. It works. Should we go to the effort of bringing in a fourth? It’s a question we’re asking ourselves at the moment.

“The balancing element of that is: what demand is the digital railway going to bring? So we’re at the start of that journey. There will be very little point, I’d guess, in building up a conventional signalling capability just at the point at which we switch into our digital signalling deployment, if that’s the direction we’re going to go in.

“The best I can say is that we’re looking hard at that, we’re looking at the demand going out, and we’ve started the work on digital railway to see what we can accelerate within ERTMS deployment. As that work matures, as we work our way through the conventional signalling work bank, then probably in a year’s time we’ll have a better view of how that crossover will look. I think we’ll have a really clear view then of what we need to do. But I would hate to build up a whole load of signal testing capability, promising great careers in the railway, only to find that there aren’t any more signals.”

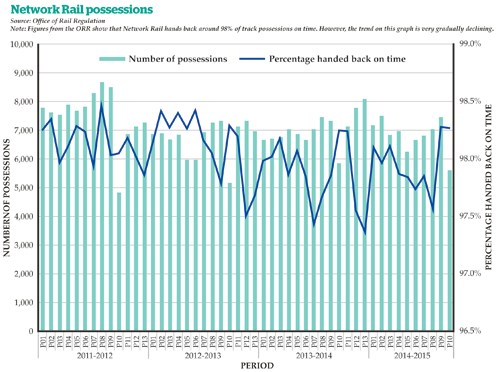

Taking Paonessa’s comments in the round, it seems that the Paddington and King’s Cross overruns were the eye-catching outliers of a process in which around 98% of all possessions are handed back on time. If there’s a flaw, it perhaps lies in the statistics fed into NR’s QSRA process.

There are flaws in contingency plans to restore train services. At Paddington there was little time to organise effective plans (made worse by the continually changing hand-back times), while at King’s Cross there was only a plan if the whole four-day job overran. There was no plan to cope with the first two days overrunning, even though it must surely have been obvious that a considerable number of passengers would be travelling.

If the railway is now to switch towards more major work on weekdays, it will have serious consequences for train operators and passengers. If it’s cheaper for NR, then it could reduce its draw on government money. This could be just as well, because (in turn) weekday disruption is likely to reduce the premium payments government receives from some of the train operators.

Peer review: Michael Holden

Peer review: Michael Holden

Chief Executive, Directly Operated Railways

The fundamental problem with the QSRA process is that the ranking which emerges from it is only as good as the assumptions on which it is based. The old maxim, Garbage In Garbage Out, still applies.

There is no substitute for experience here and a time-served old lag (dare I say it, such as myself) would have instantly spotted that a lack of sufficient train crew spare cover on a job as complex as the Holloway switch and crossing renewal represented a real threat to the timely execution of the work. Likewise, those of us who bear the scars of early resignalling commissionings in the post-Hidden and post-privatisation eras are only too aware of the risks of delays in getting Tester-In-Charge paperwork signed off, if it is not kept on top of during the commissioning process.

So, I think the real issues from these two high-profile overruns are likely to be around the quality of input to the QSRA process, and the seeming inability of our industry to remember expensively- learned lessons from one decade to the next.

There is a difficult trade-off to make between carrying out the work required in a cost-efficient way and reducing the risk of an embarrassing overrun. Judgement is involved as to how much insurance the industry (and eventually, the taxpayer) is prepared to pay for.

I reckon that the best balance is probably likely to lie around the 95% level for high-profile pieces of work such as these, always providing the 95% confidence level is real and not imaginary.

Of course, one should not just consider the risk of an overrun, but also how long that overrun can be before it becomes seriously embarrassing. In the case of the Holloway S&C renewal, there was probably a window of a couple of hours or so when an overrun would have caused some disruption, but would not have been catastrophic. Consequently, good QSRA reviews should also consider the likelihood of completing works one, two or three hours late as part of that decision-making process.

My biggest concern now is that there is bound to be an over-reaction to these particular possession overruns, owing to their high-profile nature and the damaging political fallout.

I have heard talk of Network Rail insisting on additional contingency time being added to all renewal and enhancement works for the foreseeable future. This will have a dramatic impact on NR’s ability to meet its output targets and its efficiency targets for CP5. More insidiously, for the long-term stewardship of the network, it will also result in the de-scoping of projects that are already scoped and sitting in the two-year planning pipeline for renewals works.

For example, take a piece of plain line track renewal, already in the programme. Applying an additional 10% contingency allowance into a booked series of fixed-length possessions will result in a proportion of the work not being carried out. This will leave a piece of life-expired track in situ for another few years, during which time its maintenance costs are likely to rise, and its propensity to need a temporary speed restriction to be imposed or else to cause unexpected train service delays due to component failure will increase.

So, my advice to Network Rail is this: hold your nerve. Resist the urge to add additional contingency time, but concentrate your efforts instead on ensuring that you only use competent and suitably experienced people to lead project teams.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.