Read the peer review for this feature.

Read the peer review for this feature.

A Londoner travelling to work waves a debit card at a barrier. It opens. In the capital, paying for a Tube or bus journey really is that simple.

Yet a rail commuter from Basingstoke or Canterbury can’t even exchange a cardboard ticket for a piece of plastic, because the most basic smartcard technology is not yet available.

We’ve had Oyster since 2003. A smartcard has worked at every station and on every bus in Holland since 2008… and in Hong Kong for much longer. UK bus operators are also getting on with the job - they are way ahead of rail.

But the pace of change on trains - at least outside London - has been glacial. So why is the rail industry so far behind the curve, when proven technology is available off the shelf?

Because the children in the playground won’t play nicely together. The prefects have gone off to do their own thing. And the grown-ups are hiding in the staff room, instead of coming out on playground duty.

Most smartcards conform to a common standard, called ITSO. This ensures that card readers are capable of detecting products issued by a variety of different organisations. Interoperability is a buzzword. Oyster is a separate system.

“I would not touch ITSO with a bargepole, to be honest,” exclaims Shashi Verma, director of customer experience at Transport for London. “It suffers from being designed by committee at national government level 15 years ago. It is, in my view, unworkable.”

This is perhaps surprising - Verma is a member of the ITSO board. But his alternative system, using contactless bank cards, is gaining new users at the rate of 22,000 a day. It has been operating for just over a year, but already has seven million individual users - comfortably exceeding all other systems in the UK combined.

Most people expect that within a handful of years, most old-fashioned cardboard tickets with magnetic stripes will be replaced. But with what? Govia Thameslink Railway, London Midland, East Midlands Trains and c2c already offer their own smartcard systems, joined in 2016 by South West Trains. In Liverpool, Walrus is a success. In November, Nexus launched its equivalent for the North East. Manchester has struggled with Get Me There. And buses everywhere have been using smartcards for years.

Do we really need this plethora of different brands, run by often competing commercial interests, each operating in geographical silos? Isn’t that what the Government-promoted ITSO scheme was meant to circumvent? Or is it better to rely on local expertise, since the vast majority of public transport journeys are short and urban, within city regions?

“It’s basically a mess,” says Stephen Joseph, chief executive of Campaign for Better Transport. “This is a key part of the ‘Digital Railway’. It is in the doldrums, and proceeding at the pace of the slowest. That is down to a lack of leadership by the Department for Transport.”

Perhaps it is better led at a regional level? Transport for London certainly thinks so. So does the emerging Transport for the North.

“The only people who really understand how it all works are the operators,” contends Verma. “As soon as you take the design away from the operators and put it in the hands of a national body, you distance yourself from the customers. It becomes just another massive IT project.”

In a statement, the DfT responded: “Collaboration between Government, industry, transport groups and regional partners on a shared vision is the best approach to ensure the experience of smart ticketing is consistent. Millions are being invested in rolling out smart ticketing technology across the South East and we’re supporting nine city regions outside of London.”

But Verma adds: “If people think that smart ticketing is about taking a paper ticket and making it plastic, they are completely mistaken. Yet that is the core reason for the ticketing strategy nationally and in the regions. Look at what the North East or Transport for the North are trying to do: turn paper into plastic. Complete waste of time. It doesn’t add anything to the way customers access the system, and it doesn’t change the way operators run the system.

“The revolution that Oyster brought in was Pay As You Go. That liberates a huge number of people from the need to buy a ticket each time they travel. Commuters buy tickets once a week, once a month, once a year. They don’t need to interact with the ticketing system again until it runs out. But for everyone else the hurdle of having to buy a ticket every time they travel deters them from using the transport system.”

Verma says the original Oyster system could count the number of journeys, but not the number of users. The Pay As You Go system can do that - 6.5 million people. Irregular users make up the majority of travellers, and the majority of Londoners.

“Unless you can provide Pay As You Go as the core of your smart system, the whole thing is a waste of time,” he says.

“We have two different systems in London. We have had Oyster since 2003… 100 million cards issued. I could give you many statistics, but everyone knows it is a roaring success. Since the end of 2012 we have had contactless payments on buses, and since September 2014 contactless has been extended to all our transport services.

“The bulk of transport journeys are made in an urban context where the fares are relatively small. The ticket has no meaning - we are not reserving a seat for you. All it shows is that you got in at Point A and got out at Point B, therefore there is a fare to be paid. Ticketing is actually an unnecessary process for that.

“As soon as you define the ticket as a micro payment problem, you look for the most efficient solution to that, not a solution to a ticket problem. That is why contactless payment was invented. We invented it.

“We gave it to the banking industry and they ran with it. Now, if you can pay for your transport with a product that is already in your pocket, it takes away the need for you to buy a ticket at all.

“In the 13 months that contactless has been operating on the Underground in London, it has been a runaway success - 23% of our Pay As You Go journeys are now being made on contactless. That is without any financial incentive - the fare is the same as Oyster. So almost a quarter of our customers have switched to contactless, because of the convenience.

“More than seven million cards have been used already. Seven million unique users on our system. We are seeing 22,000 new cards used every day. That is an astonishing number. And they come from 61 countries. So all this stuff about interoperability has been cleared out with a machete. Our system is already globally interoperable.

“Any transport system that goes down the same path and uses contactless payments can work the same way we do. You don’t need to go and buy a Starbucks card before you get a coffee. So why do you need to do that on public transport?”

Verma says TfL’s system can be adapted to any local transport system, although not to long-distance rail, which makes up a small percentage of all transport transactions.

ITSO strikes back

Verma makes ITSO sound like yesterday’s story, which is unfair. Look at the figures: Stagecoach alone has 240 million smart transactions a year on its ITSO system; Go-Ahead has 600,000 The Key cards in circulation; Merseytravel has 150,000 Walrus cards.

“It is well established on buses across the whole of the UK with the exception of Northern Ireland,” says ITSO General Manager Steve Wakeland. “The further you go away from London, the more deeply entrenched we are.”

The technology was adopted in piecemeal fashion across the country, with individual authorities and operators using it as the basis for their own brands. Few are interoperable, and all work only within specific geographical regions.

“It did grow out of individual silos,” acknowledges Wakeland. “But ITSO can be adapted. Everyone is looking for a one-size-fits-all solution. But there isn’t one. ITSO is the most adaptable solution. The underlying infrastructure is in place - we have cards, ticket machines and gates out there.

“And in some cases the same technology can be used across modes and from one city to another. I took a Nottingham City Card to Newcastle, loaded a Metro product onto it, and rode around.

“In ITSO-land we call it the Martini Principle. Remember the old advert? Any time, any place, anywhere. The original silos from which it grew are now overlapping more and more.”

But there is no doubt that the adoption of ITSO on the railway is slower than anyone had envisaged. On October 30, Shadow Transport Minister Jonathan Reynolds asked the Government when the ITSO-based South East Flexible Ticketing scheme (SEFT) would be delivered.

Rail Minister Claire Perry replied: “Smart ticketing was taken up after 2010. Five train operators have now signed up. A new central back office, providing critical infrastructure, underwent testing in August 2015. On current plans, the South East Flexible Ticketing programme will complete in 2018.”

So the Government-led IT system will have taken eight years to implement. That’s the same amount of time taken to move from GPRS phones to 4G, and longer than it has taken to introduce fibre optic broadband to most rural areas in England. By then, even ITSO itself will be moving to mobile phone use, and Transport for London considers the scheme obsolete now, in late 2015.

The Train Operators’ View

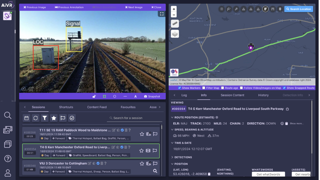

The most firmly established user of smart cards outside London is Southern Railway. Now that Southern is part of the giant Govia Thameslink Railway (GTR) franchise, The Key is being rolled out across all its routes.

Launched four years ago, progress has been slow but steady, with 50,000 journeys a week now bought on the card. Last year, TfL travelcards were added, so that season ticket holders can use The Key on the train, Tube and bus. A Pay As You Go version has been launched more recently.

“The Key will become the method of choice on our routes,” says Dave Walker, head of revenue and ticketing at Govia Thameslink Railway. “Three years from now we hope the vast majority of travellers in our area will have moved to contactless KeyGo.

“We are involved in the Government-led South East Flexible Ticketing programme. But The Key was launched before SEFT. We use an earlier back-office version, and SEFT is funding the extension of The Key onto Thameslink routes.

“It now covers almost every GTR station, and KeyGo is valid at 120 stations. Next year it will reach Cambridge, Peterborough and King’s Lynn. Your bank card is associated with your KeyGo card, so you can tap and go from (say) Gatwick to Brighton. It will work out the correct fare for you and charge you afterwards. This is particularly innovative – no one else has this.”

KeyGo is linked to Metrobus and Brighton & Hove buses. So it is possible to travel by train to Brighton, by bus to Eastbourne, and then join another train. Not many people do, but even so this is the closest non-metropolitan system to London’s contactless payments.

“Interoperability is important,” says Walker. “We would like to reach a point where our card will work on the South West Trains system and vice-versa. As it already works on the travelcard area, our cards are read by the machines at Waterloo… no problem.”

c2c is a more recent convert to smartcards that also work in the London travelcard area, using an evolution of the Southern model.

“We are part of the SEFT scheme,” explains spokesman Chris Atkinson. “We went live one year ago, and 20% of our season ticket holders are now using it.

“From February we will launch an automatic delay repay scheme on the smartcard, if your train is delayed by two minutes or more. You will get 3p per minute put back, up to 30 minutes. Above that you get 50% off the fare. The automatic credit gives you money off your next purchase. So for the following season it might mean £40 to £50 off. You will have tapped in and tapped out of each service, so we will have a record of how long every journey will have taken.

“We are also doing a trial with Barclaycard for payment bracelets called bPay. Each has a chip like a contactless card. It’s a wearable system, a bit like a Fitbit. We are sending 8,000 of them to customers in East London and Thurrock who are currently buying paper season tickets, or those who use Oyster Pay As You Go a lot. The contactless fare is cheaper, so they could save up to £80 a month over a paper ticket.”

It works like a digital wallet. Customers add funds from their existing Visa credit or debit card, and it can be set to top up automatically whenever the balance falls below a threshold. The full c2c route will have contactless payments from 2017.

South West Trains is a step behind, with the first passengers due to switch from cardboard to plastic in 2016. Staff already have smartcards, with 6,000 issued last summer for familiarisation and testing. The company says it identified some glitches, which are being fixed before it becomes available to half a million season ticket holders.

“That will come in parallel with a new website and booking engine,” says SWT Managing Director Tim Shoveller. “The bit of plastic in the customer’s hand is actually the final bit of the jigsaw. The rest all has to be in place first.

“We also have a programme on the Portsmouth line running trials to Waterloo, but at the moment the cards can’t be used further than that. We haven’t yet got agreement with TfL to sell season tickets through to the Underground. We can’t sell outside SWT. We were hoping to have that resolved a long time ago. The technology is there - it’s about agreeing the details.”

SWT accepts that the SEFT programme has been slow and difficult, but believes the Government will specify it for other parts of the country as part of franchise requirements.

“It is what the vast majority of our passengers want and need,” says Shoveller. “London can afford the significant infrastructure required to gateline every station. Not a problem here, because of the vast volumes on a fundamentally profitable railway.

“But I recognise that there are parts of the country which will not support the levels of investment to fit gatelines at every station and then staff them. And you need that if you’re going to replace magnetic stripe cardboard with smartcards.

“We will find that the smartcard itself will soon be on a phone. The time during which it is a physical card will be relatively short. But it is too big a step to go to the phone now. And nor do I think we can wait for that - the cardboard with a magnetic stripe is 1980s technology that is well beyond its sell-by date.”

Shoveller points out that holders of cardboard season tickets are not necessarily given a replacement if they lose one. That piece of card can be worth £5,000 or more, and Shoveller notes: “I can’t just give you another one, because you might pass it to someone else. Sadly we know that happens.” A smartcard, on the other hand, can simply be cancelled and a replacement issued.

“Straightaway that changes the relationship with our passengers,” he says. “At the moment we know very few of them. They can buy their season tickets without leaving us the means to contact them. With smartcards we can know who they are, if they choose. We can know if they are frequently on a particular train. And if there is a problem with that train - a cancellation or a delay - we can let them know.

“If we do overnight engineering work, we have no idea who is going to be on the first or last train that gets replaced by a bus. We can’t contact them to warn them, we just have to put up some signs. In future we can warn them in advance. It changes the whole dynamic. That is worth more to us than just the plastic card itself.”

Smartcards should enable another key demand by passenger groups: the flexible season ticket for people who do not make the same journey to work five days a week.

“The Government has committed to this publicly,” points out CBT’s Joseph. “But the Department does not have the faintest idea how to make it happen.”

South West Trains offered to take part in a flexible season ticket trial, but was not selected. Shoveller admits it has been hugely frustrating, but explains the scale of the problem:

“The challenge is not just how to issue a flexible ticket, but how to do it in a way which also tackles the overcrowding issue. There is no point doing it if it just reduces income for the railway.

“From Monday to Thursday, the level of overcrowding is pretty consistent. On Friday, we carry a lot fewer people. If people could pay for travel on four days a week, we think most people will choose Friday as the day off. That is the day when there is already spare capacity on the trains. That will cost the railway, and ultimately the passengers, because we have to run the same amount of rolling stock on Fridays as on other weekdays.

“So do we really want to give people a discount to travel on a day when there is spare capacity? Or do we want to use this technology to incentivise passengers to travel when space is available, thereby reducing overcrowding in the peaks? I’m all for a sensitive approach, but we do have to achieve more than just making season tickets cheaper for some. Having emptier trains would seem to me to be the wrong thing to do.”

The DfT responded in a statement: “We are actively working with the industry to test a range of options and to identify how flexible tickets can best be achieved.”

The Northern View

“We have a remit to create a smartcard solution across the North,” says David Brown, the newly appointed chief executive of Transport for the North (TfN). “We need an outline implementation plan by March.”

The former Merseytravel boss is based in Manchester, which has had a troubled history with its own smartcard system. As yet, TfN does not even have statutory status. And Brown has just a handful of staff, largely loaned from other local authorities, while he establishes what he hopes will become a northern equivalent of Transport for London.

“We need to build on the schemes already in place,” he says. “The Walrus card in Liverpool is the biggest smartcard system outside London. What we do must go beyond that. It needs to be pan-northern, and it needs to provide real customer improvement.

“The pan-northern card must incentivise people travelling between city regions. It has to add value. It must be there not merely because we can do it, but because it is better.

“I’m not convinced it will be card-based technology. I think it will be more personalised - it will allow existing cards to plug into it. Talking about the technology comes from the wrong direction. It has to be about the person.

“It needs to work for me - working in Liverpool with business to do in Manchester, then going home to Macclesfield. It has to offer a price incentive by card, phone, watch - whatever is suitable for me. But it also has to work for someone who lives in Bootle and who travels into Liverpool every day for work - sometimes by train and sometimes on a bus.”

Brown says he sees little point in a UK-wide smart ticketing system, pointing out that Scotland is currently developing a national card because there is sufficient demand there.

“In all seriousness, the cultural differences between London and the North are massive,” he explains. “And even within parts of the North the differences are large.

“Here in Liverpool, moving people to a card that they have put their trust in, and loaded money on, is a big step. I live near two people who have just for the first time trusted the Walrus card enough to put three quid on it. But my kids, who are quite cosmopolitan, trust implicitly the account they have set up to pay through a phone, because they have downloaded the bit of software that checks what it does. It varies enormously.

“We have a window of opportunity with the new rail franchise owners being put in place in the coming months.”

The Dutch Model

Anyone who has tried train travel in the Netherlands can see how far behind the British system has fallen. The O-V Chipkaart operates on practically every train and every bus in the country. It is simple and seamless.

You tap it against a reader at the start of your journey, and tap it at the end. A train guard checks its validity against his hand-held card reader. A bus driver hears the “beep” as you board the vehicle. As a user, all you have to do is make sure it has sufficient credit. Queues for tickets and crowds at the gateline are consigned to history.

“The Dutch O-V system is an ITSO-like operation but done very successfully,” says Verma. “It is a single card that can be used anywhere. But you still have the problem of getting the card and topping it up. It doesn’t liberate people from the need to buy a ticket.

“I don’t want to belittle what they have done, because they have achieved what ITSO never managed. And it went live in 2008, when contactless bank cards didn’t exist.

“O-V has a heart where all the clearing is happening. It is a centralised system where the company that runs the Chipkaart stands behind everything that is going on. With ITSO in the UK, it was decided very early on that no one organisation would control the technology. So it couldn’t happen here.”

ITSO’s Wakeland says the Dutch model is, in many respects, the same as his system: “It works on pretty much all services - that’s the difference. They’ve just chosen to use a single badge which every passenger recognises can be used everywhere. In the UK the cards look different in different places - Stagecoach Smart, The Key and so on. But the underlying technology here is identical below the branding.”

John Verity is both chief advisor to ITSO and chairman of the Smart Ticketing Alliance, a not-for-profit organisation registered in Brussels that brings together a network of smart ticketing schemes across the world.

“The Dutch card is a standard e-purse,” he explains. “You put at least 50 euros in it. Every time you take a journey, you buy a local ticket with that money. It looks great, but it is in effect like Oyster Pay As You Go. You are not buying a through single ticket, which means you are not necessarily getting the best value. It’s fine where there is only one operator - Amsterdam or Rotterdam. But if you travel for part of your journey on a Veolia service, you can end up paying two maximum fares.”

Wakeland says the technology to use a system such as the O-V Chipkaart already exists in the UK. But no one has tried it.

“We have a standard across ITSO that every card must contain - it has a national e-purse on it. Sadly that purse has never been used. We could have exactly the same implementation that they have in the Netherlands if someone had the political will and the leadership to start using what is already there. You just have to sign up for a back-office facility that assigns the fares to the organisations that are part of it. That’s where you need national leadership.

“Multi-modal smart ticketing like the Dutch have is coming together outside London all over the place. But the biggest challenge has been getting all the operators to sign up to the apportioning of revenue.

“It is not the technology that has been holding the UK back. Those business rules have been the issue, both on rail and on buses. Everyone has to play nicely together.”

Verity offers his international perspective: “We have a very different business model in the UK to anywhere else in Europe. And the business model makes smart technology very difficult to implement. The technology can cope with almost anything you care to throw at it. But the lack of an agreed tariff structure here makes it extremely complicated to use.

“If you’re going from Rotterdam to Amsterdam there are only two fares - one for the high-speed service, and one for everything else. If you travel from London to Manchester, there are hundreds of different fare options.

“In the Netherlands you have a clear tariff structure led by federal government. It is simple and understandable. I used to be operations manager for the Rail Settlement Plan. We were coping with 350 million different fares at RSP. That’s between only 3,000 stations. Then add in the different bus fares - my local one has four different rates from my house to the station, which is a five-minute journey. That does not happen in any other country.

“People are now accepting there is a lesson to be learned here. A simplified structure is the key to smartcards. Transport for the North is starting from scratch. It has an opportunity not just to replace paper tickets with smart ones, but also to look at the structure of ticket pricing. It can use the smartcard to give people a more straightforward and more easily understood pricing system.”

Wakeland concludes: “TfL has a regulated market and a simple fare structure, like the Netherlands. We call it account-based ticketing. What they have done with the contactless bank card has been relatively easy. If you tried to use the same model elsewhere in the UK, where fares are unregulated, it would be very difficult.”

Verma says that the Dutch - already far ahead of most of the UK - are now looking at updating and reforming their system to make it more like TfL.

“The Dutch want to move to contactless as well. We are in discussion with them,” he says.

What Happens Next?

The Smart Ticketing Alliance has been looking at door-to-door journey planning.

“In the UK this is well organised,” explains Verity. “The problem is translating journey planning into ticketing, so that you can do both in one place.

“Two things stand in the way of progress. First, mobile phones don’t yet have a common standard in terms of contactless smartcard operation. We are looking at that with phone manufacturers - they must work across all systems. Second, we are missing the ability to plan a journey and pay for it in one place, then hold the e-ticket there.

“Try explaining to an American or an Australian how our rail fares work. It’s almost impossible. When ATOC sells a UK rail ticket to people outside Europe, it is sold on a zonal system. London to Edinburgh is a three-zone ticket. They buy in the system developed for Swedish rail by a company now based in London - SilverRail.

“This is what Transport for the North should look at: a system that is easy to use by a person who wants to buy a ticket but who does not know exactly what ticket they want. This needs to be done through a mobile phone or tablet.

“Seventy per cent of all journeys in the UK do not involve buying a ticket at the time of planning the journey. The figure is similar in France or Germany. It is pre-planned by buying a season ticket, or an advance fare, or a concession, or the ticket is bought through some other process. And that figure is increasing.

“People want certainty on how much they are going to pay. SilverRail’s expertise is on the planning side - it wants to be an aggregator, seeing a journey across multiple operators and different modes, and calculating it all in one place. What we need is a system that sells the ticket in the same place. We want it to say: ‘Trust me with your credit card number, and I will go off and buy it for you.’

“SilverRail is not alone in that - other big organisations want to do the same. Amadeus does it for the airline industry. For example, a flight with EasyJet or Ryanair, connecting to British Airways long haul to Australia, then a local flight there - done with the same credit card to ticket all the way through.

“The same thing could happen on rail and bus. An electronic wallet that contains multiple tickets, bought in one go. For that you have to trust the tariff system to offer you the best value for money. That is harder in the UK because the pricing structure is so complex. The technology is there, but the fare structure is not.”

ITSO’s Wakeland says the linking of journey planning, real time information and mobile phones is the key goal for the next few years: “This is what people really want - loading your information onto a device which shows the journey options, pays for them and keeps you updated during your journey. We are working on bringing ITSO ticketing to mobiles. That’s the future. But it will involve simplifying fare structures, if it is to work by merely pointing your phone at a barrier.

“It can be done technically if the political will is there. I think it exists in Transport for the North.”

Ditch ITSO?

The move from cardboard tickets to smartcards has been strangled by a lack of leadership, particularly from central Government. It has taken years longer than anybody expected, characterised by obfuscation and indecision.

“You have to find somebody with the commercial, technical and operational capability to pull this off,” says TfL’s Verma. “Central Government has none of those three requirements.

“They should let us into the tent, and let us help them sort it out. That is the right answer. But it was the right answer ten years ago as well. And if they don’t let us in, then frankly five years from now the system is going to look pretty much like it does today.

“The DfT has specifically said we have no remit outside London. They make the rules. If that is the policy we cannot do anything about it, even though we have a system that has already been proved, and which can work everywhere.”

Verma believes ITSO is fundamentally flawed.

“Having watched this for ten years, it is incredible how vast amounts of money are being spent on this, with practically nothing to show for it. Central Government is investing money for absolutely bizarre reasons. A lot of money, and more importantly a lot of emotion, has been invested in ITSO by the Department for Transport. And that makes life very difficult.

“Let me press the money point,” he continues. “Fantastic amounts have been spent on smart ticketing.

“The Oyster card system in 2003 cost £50 million. Since then we have spent another £50m. £33m went into extending Oyster Pay As You Go to the national rail networks in London - that was the total cost of putting Oyster into 400 stations. Against which there has been extensive academic analysis of the benefits of Oyster Pay As You Go. It shows the increase in revenue is of the order of £100m-£120m per year. It is not difficult to see the investment case.

“Likewise the cost of contactless was £68m. £24m of that was bringing an asset refresh. So the real cost was about £44m. And we have seven million users already. These are not seven million people who are being forced to use the system - they have alternatives. They are choosing it.

“Now look at ITSO. The cost is definitely in the hundreds of millions of pounds. We do not know how many hundreds. And the only substantial successful use of it in the whole country is with concessionary passes for the elderly.

“My suggestion to anyone, operating transport systems anywhere in the world, is to stop investing in technology that is already 15 years old and go with the most modern solution… contactless bank cards. Your passengers already have them.”

CBT’s Joseph adds: “When the Public Accounts Committee finds out, it will fry the Department for Transport. TfL has been offering for a long time to extend its ticketing to Gatwick and Luton airports, so that visitors don’t have to buy a rail ticket and then an Oyster card. It has been turned down because there are fears of revenue abstraction.

“There is a large chunk of the London commuter area that does not have this stuff, when it has been offered on a plate. I’m not sure ministers realise the extent to which DfT pride had stopped them delivering tangible benefits for passengers. It is trying to make its own SEFT system work. And it’s not at all clear that it is working in any meaningful way.”

The DfT responded in a statement: “Through our investment, smart season tickets are already available through two operators in the South East. Our investment has offered the foundations for smart ticketing in the Midlands. We are clear that rolling out smart ticketing in the North is a priority, and we are working with local authorities to deliver this as soon as possible.”

“What we have done is world leading,” Verma concludes. “And we are in discussions with practically every major city around the world. They want to emulate what we have done. Every large city you can think of - New York, Paris, Hong Kong, Singapore - they are all talking to us. My recommendation is that the rest of the UK cannot ignore this any more.”

Conclusion

Is Shashi Verma right? Is smartcard travel already yesterday’s technology? There seems no immediate prospect of an equivalent of the Dutch O-V Chipkaart, even though that has been successful since 2008. In the UK, that puts us eight years behind already.

Verma thinks we should skip that stage altogether, and adopt London’s contactless bank card system. If he’s right, it’s as if the Government is urging us all to buy our music on CDs instead of on scratchy vinyl, at a time when everyone else has already tried downloads from iTunes and is now moving on to storing their music in the Cloud.

But most journeys are local. So if we adopt a hotch-potch of options, each of which satisfies a local need, how much does it really matter that a smaller number of long-distance travellers or overseas visitors are significantly disadvantaged?

It’s clear that outside London, we are falling way behind the game. There are two technical paths we could follow, each of them viable now. One is not being pursued at all, and the other is not being pursued with any particular sense of political urgency. One rule for London… another for everywhere else.

Read the peer review for this feature.

Peer review: Trevor Birch

Peer review: Trevor Birch

Partner, PA Consulting Group

This article raises many implicit questions, and I’m going to address a few of the most important:

Are we building with the right technology?

Why is it taking so long for smart ticketing to roll out in rail?

Is government providing the right leadership?

I’ve spent the past few years working closely with the DfT, trying to drive SEFT forward and articulate how it fits into an emerging national strategy for smart ticketing. SEFT is implementing an ITSO scheme in the South East, but is also looking more widely at the national context for smart ticketing on rail, options for contactless payments, requirements for Transport for the North, and how rail interacts with other modes. It’s a complex landscape, and many of the arguments are simplified too much.

Are we building with the right technology?

The article seems to suggest that ITSO is obsolete, stresses a lot of the benefits of contactless, and points towards the adoption of mobile technologies. It recognises that the majority of journeys are made in an urban environment, but skips over the realities of national rail and the (very) differing needs of the people who travel on it (commuters, infrequent travellers, cities, rural environments and long-distance travel). There has been significant debate over the past 12 months, largely within the Rail Delivery Group, and the emerging consensus is that the future will not be a single technology, but multi-media:

- Card based tickets in urban/city areas - because cards are physically resilient and fast processing, and cities have good connectivity.

- Barcode tickets - for long-distance travel and potentially rural areas where there is little connectivity.

‘Mobile’ is misleading as an option. Functionally, mobile replicates a card (contactless or ITSO) or barcode, so it makes little difference. The advantage of mobile is its ability to link internet access (for information and payment) with the same device that can carry your ‘ticket’. The functional advantage is its potential for geo-location to record the start and end of your journey, replacing ‘taps’ and the need for costly infrastructure in stations, such as validators.

Before consigning any technology to the bin, or declaring one the best solution for rail, we should consider the maturity of the different technologies and their advantages/disadvantages.

ITSO is mature, well-established on buses and exists on parts of rail, but its deployment has been fragmented. Its biggest advantages are interoperability (it is designed so different systems can talk to each other), products are held on the card (which means you don’t need WiFi on trains or 3G for revenue protection), and it’s good for high-value products (long journeys and seasons). Downsides include the need for lots of infrastructure to collect ‘taps’ at the start and end of journeys, and customers having to purchase cards in advance (so it’s not great for turn up and go travel).

Contactless is a massive success in London and offers great potential. The advantage is that many people have cards, and it’s easy for turn-up travel. Disadvantages include reach (not everyone has a bank account), it’s not great for high-value fares (customers are uneasy ‘tapping’ if they don’t know how much they will pay), and there is no agreement yet on interoperability (journeys starting and ending in locations that are not connected to the same back office).

Barcode has been proven to work in trials on national rail, but is not yet rolled out at scale. Nor will slow processing speeds work well for large volumes of passengers arriving at busy stations during peak. It offers good advantages for infrequent travellers, long-distance travel, and potentially in rural areas.

Mobile offers great potential where payment and tickets can be put on one device. The downsides include reach (many people don’t have smartphones, large portions of the population don’t download apps, and only small number of phones can be used to make payments), and the lack of established standard for carrying ‘tickets’ on phones or processes and equipment for geo-tagging.

As such, I don’t think we are building the wrong system - we are trying a number. ITSO has a head start and offers immediate interoperability, but contactless is developing quickly and will be a big part of the future. The ambition is ‘account-based ticketing’ where the technology is less important - it acts as a ‘token’ to pass through gates while your account registers your right to travel (ticket), proof that you have paid, and enables payment to be checked (revenue protection). Link an account to an ‘engine’ that calculates fares and you can offer Pay As You Go, price capping, delay repay or flexible pricing to incentivise travel at different times of day or days of the week. ITSO can support this, but is only one option on the journey.

Why is it taking so long to implement smart on rail?

Yes, progress on rail has been slow, and John Verity makes some good observations on the reasons why. London has been able to implement its systems quickly because it is in control - of fares and of the bulk of transport modes. National rail in the UK is much more complex

- The industry is fragmented - with multiple, competitive operators who have different (at times divergent) commercial interests. Legal and commercial frameworks are essential to bring operators together and create financial settlement, but can take years to agree.

- The fares structures are complicated - with over 350 million permutations

- Everything is contractual - change has to be managed through new franchise commitments or amendments to existing franchises. TOCs are incentivised to meet their contractual obligations and not much more

The positive news is that momentum is building. There is £150 million of funding for Smart on Rail in the North, the Payment Cards Association is co-ordinating thinking on how contactless may work on national rail, and ATOC has ideas on the use of barcodes. SEFT provides funding and is bringing together a critical mass of TOCs in the South East who will operate within a common scheme.

Is the Government providing sufficient leadership?

My observation is that the Government has taken a stronger role in recent years because things were moving slowly - it has taken a lead role in SEFT in promoting multi-operator schemes in cities, and is supporting Transport for the North.

There is an argument that government should do less - that rail is a free market economy and that government should not be involved. This is happening. SEFT will hand over to the Rail Settlement Plan, TfN is taking responsibility for solutions in the North, and the RDG has a working group looking at smart.

How do we move forward?

We need to focus on the customer, not the technology. We need to simplify ticketing, rather than replicating it on smart, and use fares to incentivise take-up. Unfortunately for some, the Government has a key role in much of this.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.