Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

"If there is an industry cascade plan within the Department for Transport, it’s not one that is shared with stakeholders.”

Tim Burleigh should know. He’s Relationship Development Manager at Eversholt Rail, one of the UK’s three big rolling stock leasing companies.

He continues: “We all have our thoughts on how existing rolling stock could be deployed in the future. We share our thoughts with the Department, but we don’t get the same back.”

That certainly seems to be the official Government line. Asking for an explanation of the current state of the rolling stock market resulted in this cut-and-paste response from a DfT spokesman: “The Government believes in a market-led approach to rolling stock, and therefore does not believe that the cascade of units between franchises should be planned by officials within the Department for Transport.”

Certainly Burleigh believes there is a genuine market, with real competition to supply the most suitable trains to the appropriate users. Well, he would say that!

“Very much so. Very strong competition. With Thameslink particularly, Crossrail yet to come, and the Hitachi IEP order creating pools of existing rolling stock which has future potential use. There are more trains in some categories than there is current demand.”

But not everyone agrees with the DfT’s official stance.

“That’s bollocks. Utter bollocks,” says a very senior executive in the passenger rail industry, who prefers not to be identified (for obvious reasons).

“DfT claims it does not interfere in the rolling stock market. But in reality it does. There is a question about whether it is really a market anyway. When demand exceeds supply, normally supply is increased. That doesn’t happen for rolling stock in the UK, which is why we have a shortage of trains, particularly diesel ones. I would say it’s not a market.”

This is not a view shared by all train companies. MTR operates London Overground, and will soon take on the Crossrail concession.

“I’d say there is a genuine market,” says Jeremy Long, MTR’s CEO, European business. “Of course, the DfT has control over franchises, and it can put in place specifications which dictate much of the rolling stock. But as there is more demand than supply, everyone wants to get their hands on second-hand DMUs and EMUs. There is a lot of antiquated stock that the industry would like to see pensioned off, but as there isn’t a replacement available, then there is a market for those trains.”

There is a plan. It is called the Long Term Passenger Rolling Stock Strategy for the Rail Industry, and its purpose is to make clear the level of demand for new trains over the next 30 years. Now in its third iteration, it was updated at the beginning of March. It is put together by the ROSCOs, by the Rail Delivery Group, by the owning groups of train operators and by Network Rail, under the leadership of former Eurostar chairman Richard Brown.

The strategy discusses the relationship between the rollout of overhead wires and the rate at which new electric trains will need to be ordered.

It anticipates that the total passenger fleet will grow by between 52% and 99% over the next 30 years, and that the proportion using electric traction will rise from 69% today to more than 90%. This means that between 13,000 and 19,000 new electric vehicles will be required.

New trains

Last year’s version of the strategy stated that fewer than 100 new diesel vehicles would be needed, none of them in the present decade. Now there has been a sharp shift of emphasis. There is “a potential requirement for 350 to 500 non-electric vehicles, for a variety of urban stopping, rural stopping and inter-urban express services. In the longer term, up to 1,500 new self-powered vehicles may be required.”

These will be required because of the existing levels of crowding and strong growth in demand on non-electrified routes. The strategy also assumes that all 290 Pacer vehicles will have to be replaced - this is specified in the Invitation To Tender for the new Northern Rail franchise, for completion by 2020. Northern is the largest user of unpopular Pacers, which are also operated by Arriva Trains Wales and First Great Western.

To meet demand, there would have to be an average build rate in the coming years of a dozen vehicles each week. In the five years to April 2014, the build rate was a third of that figure… four a week.

The strategy also states: “Government policy is that rolling stock procurement should, other than in exceptional cases, be franchise-led.” Yet in the big recent orders, that has not happened.

Government led the way in procuring IEP trains from the Japanese company Hitachi (at the time of writing, the first vehicles are on board a ship heading to Southampton). Government led the way on buying new Thameslink trains from German manufacturer Siemens. And together with Transport for London, Government led the way on the Crossrail order from Bombardier in Derby. It is undeniable that politics plays a significant role in the procurement process.

But the strategy says remarkably little about the manner in which cascaded second-hand stock should be used. So what will happen to the rolling stock that will be displaced, and who will be in charge of it?

We will get a detailed analysis from Tim Burleigh at Eversholt. And we will hear from Northern Rail, which will inevitably be on the receiving end of cascaded stock from southern England.

But first, back to our senior rail industry figure for a forthright off-the-record briefing. Read this, and you’ll know why we’re not naming him… or her!

“There was a stage where the old Strategic Rail Authority had an industry plan. That was dropped. It was deemed not appropriate for the Government to meddle in the rolling stock market. That’s a line which DfT trots out today - they’ve given it to you again. But in fact, they meddle in it all the time.

“And they have to. Electrification is going backwards, so the need to answer the shortfall is getting greater by the day. There is a disconnect between the process of electrification and the supply of trains. The new trains are coming faster than the wires to power them. Who is in charge of this? The DfT.

“That is a problem. DfT does not have the capability and knowledge and experience to perform this function, which is to have a joined-up plan for UK rail. That is why it created the Office of Passenger Rail Services and appointed Peter Wilkinson to help give it the capability to perform this function. Wilkinson holds all the levers of this industry. Directly or indirectly his staff control the whole bloody thing. But ministers try to pretend they don’t, because it’s then easier to bargepole the rest of us when something goes wrong.

“Who writes the ITT for the franchises? The DfT. It is deciding what the future of the rolling stock strategy will have to be by the way it writes each ITT. DfT is front and centre of the strategy.

“Rolling stock strategy should be planned over the 30-year economic life of the train, not the eight or ten years of a passenger franchise, let alone the two or three years of the current short-term extensions. We are locked into this hand-to-mouth existence. Every bidder for every franchise has to comply with whatever the ITT says. We have politicians promising that the North will get rid of rubbish Pacers. DfT is saying to itself: ‘They might be rubbish, but they’re cheap.’ As I said, all roads lead back to the DfT.”

What does the Department make of this? Sorry, folks, all we can do is quote from the two-paragraph statement on offer:

“When proposals arise, such as the transfer of the nine Class 170 trains from TransPennine, officials will work with the industry to help find a solution, but the Department has made it clear that it expects train operators and rolling stock companies ultimately to resolve such situations.”

Government intervention

Certainly there is some Government intervention. Look at Northern Rail, currently in a short-term contract pending the letting of a longer-term franchise.

“We signed our franchise agreement on March 26 and started running it on April 1 last year,” says Northern’s Managing Director, Alex Hynes. Since then we’ve signed two variations to the franchise agreement to bring in more, better and electric trains. It’s not long-term planning. But we get 20 electric trains to operate in the North West when the wires are ready, which they’re not yet. The second variation was a complicated solution between TransPennine and Northern to maintain capacity when the trains are switched from there to Chiltern.

“Rolling stock comes under what are called ‘key contracts’ in the franchise agreement. And you need approval from the Secretary of State to make changes to them.

“The North is used to having to put up with poor-quality rolling stock, sent to us from elsewhere. Northern is the last big TOC to get the massive rolling stock investment it needs. That’s a consequence of it being let on a no-growth, no-investment basis ten years ago.

“DfT is now in the process of procuring the next Northern franchise, and wants it to be completely different. It realises the North deserves better. So let’s assume that’s going to get fixed.”

The rolling stock strategy assumes that electrification will proceed at broadly the current rate for the foreseeable future. Tim Burleigh at Eversholt highlights the franchising hiatus as the biggest hurdle to be overcome before the rail industry can move into what he calls a “steady state” of cascading.

“We’re in a transitional period as a result of the West Coast franchising issue in 2012 and the Great Western franchise that followed it. That, of necessity, has given us some short-term planning headways, which cause some difficulties. They are restricting some of the longer-term possibilities that we all think are best for the industry.

“The reorganisation within DfT is helping. But the delay and uncertainty around some of the electrification has an impact on what is a feasible cascade and what isn’t. If the wires aren’t up, it is impossible to run an EMU unless you pull it with a diesel locomotive, which is not efficient. That is a real challenge.

“In this transition there is a mismatch of availability. The EMUs coming out of Thameslink and Crossrail might be available earlier than the wires are up to use them. Managing growing customer demand is going to be a problem, because for a while there will be no wires and no power supplies. That will be one of the biggest challenges over the next few years, and we are concerned that it will compromise the long-term vision that we all want to have.”

Our nameless senior executive is able to put this more bluntly:

“The electrification timescale is all over the place. It’s going backwards day by day. In a sensible, rational industry we would look longer term. Electrification is not moving far or fast enough that it will release enough diesels to be deployed elsewhere for network growth. We will have to end up buying some new diesel trains at the same time as we spend money on electrification, which is daft. It might mean we can’t even get rid of Pacers.

“IEPs are going to arrive late. They’re going to have to run diesels under where the wires should be for a while. Scotland thinks it’s going to get the old HSTs when they come out of Great Western. It wants to create a mini inter-city network by shortening some of the HST formations. But they can’t get those until IEP is completely done. It is an utter mess.

“We think there’s going to be a surplus of electrics coming, but we’re not sure when. There will only be a genuine market for rolling stock when there is a surplus, and it will be fascinating to see what that does to the price.

“On Crossrail and Thameslink new electrics replace old electrics, so in theory the cost of those should fall. But you can’t run the old electrics if the wires haven’t gone up in time - it’s all out of balance. In the meantime, there is an acute shortage of DMUs, and the ROSCOs can charge whatever they like for them. Train operators - and ultimately taxpayers - just have to pay up.”

The 2015 rolling stock strategy includes a tacit admission that electrification is indeed falling badly behind. It’s the first time this has been officially recognised. From the low, medium and high scenarios of the rate of installation of wires, it adopts the lowest rate. And it warns: “Any reprogramming of the completion dates of the currently planned electrification projects would have adverse consequences for rolling stock:

- Slower achievement of the additional capacity required.

- Higher capital cost and whole-life costs of any new diesel vehicles.

- Incremental costs associated with short initial leases.

- Longer introduction timescales compared with those for new electric vehicles.

- Lower reliability of diesel vehicles.

As this issue of RailReview went to press, it seemed increasingly likely that the first evidence of this will be a small fleet of diesel-only IEP trains to run from Paddington to Penzance, to be specified in a new First Great Western franchise in late March. They are rumoured to be by some margin the most expensive trains to be ordered.

Other options include building new self-powered trains as bi-mode vehicles to future-proof them. The strategy document also suggests that they could be unpowered, to be hauled by either diesel or electric locomotives. But time is tight - whatever solutions are picked, the trains are needed in service by 2020.

With passenger growth consistently exceeding 4% a year, the nominal surplus is likely to be absorbed by the need to increase capacity, doubling up formations. Burleigh explains that an ideal cascade would involve moving an entire fleet of trains from the South to the North in a single move.

“You need a critical mass of a type of rolling stock to build up expertise and maintenance. The more you have, the higher the potential availability. Our suburban fleets are reaching 93% availability, which surpasses that of newer trains. That only happens when you get enough of them in one place, giving passengers predictability and reliability.

“We want to avoid small fleets of varied stock. The guys at Northern Rail are the obvious victims of that - they would really benefit from standardised trains.

“But if you’re moving large-scale fleets of common units from London to the North West, there are very few places that could accept the entire fleet. If you do have to split it, you want to do so to as few places as possible, so that the issues of sharing spares and support equipment are minimised.

“We share this information with the DfT and with franchise bidders. There are short-term problems to overcome, but there is a general recognition by everyone of where we want to be.”

Any deal covering the next decade will entail shunting the older trains from London and the South East to the North, and also to South Wales. Politicians have been quick to criticise this priority given to cushy commuters into London, with their lovely new trains fitted with WiFi, air-conditioning and the latest information systems. But almost two in three passenger journeys are in that part of the country - the investment goes where the future revenue can support it.

“This whole thing about cast-offs: I don’t buy that,” says Northern’s Hynes. “The age of the train is irrelevant - what matters is the condition of the train. Have a look at the Class 455s on South West Trains. Those trains are ancient but they’re brilliant - a transformational refurbishment. The customer environment is good, they’re reliable, and they’re safe. They’re everything a train needs to be.

“The key thing is that cascaded trains have to be delivered fully refurbished, with everything done. Some people in the North are complaining about getting the South’s rejects to operate beneath the wires between Manchester and Liverpool. But actually we’ve refreshed them - we’ve put audio and visual passenger information in them, and repainted them. My customers will think they are like new. Rolling stock quality is on the political agenda here. That can only be good.”

Burleigh agrees: “There are lots of suburban and inter-regional electric trains coming up. When we transition these to a diesel part of the network, passengers will not want to see trains that fail to match the capability, the comfort and the information provision of newer trains. Lower quality is an inhibitor to future growth. The new trains coming elsewhere lead to higher expectations for other trains, too.”

But he warns of very real affordability constraints: “Electrification costs have gone up. We are dependent on whatever the pace and scale of the future electrification programme will be. It’s still very much in flux.

“There will come a point where the balance of funding between electrification against new rolling stock will have to change, and that may mean we see some of the existing stock retained for longer than anticipated.

“We need to align the fleet with growing expectations - some elderly fleets are unloved and much derided. That’s why there has been a lot of investment in demonstrator trains, to show how a new-train feel can be imparted to existing trains. Several regions will still retain unelectrified routes, and there will be a medium-term need for self-propelled rolling stock. And that currently means diesel.

“We have to look at whole-life assets. We are certainly looking at retractioning some of our existing trains. And while there aren’t current alternatives to diesel propulsion, the automotive sector is moving on apace. So it could happen.

“So when we engage with manufacturers about any future new diesel stock, we are looking for modular designs with the potential to accommodate a future upgrade when those alternatives mature - perhaps in the final quartile of the asset’s lifespan. Look too at the work sponsored by Network Rail on an independently powered electric demonstrator. You could see for some routes that might one day prove attractive.”

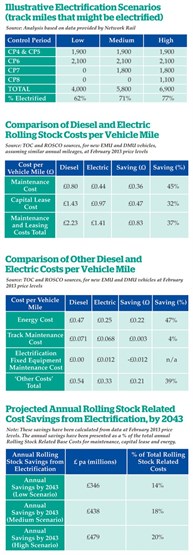

The rolling stock strategy document sets out a substantial projected reduction in costs, resulting from the switch to lower-maintenance electric traction and a stable production rate of units that share common standards.

At 2013 prices, the strategy states that the maintenance cost of a diesel is 80p per mile, compared with 44p for an electric train. Combined with the lower energy and capital lease costs, an electric train works out as 37% cheaper to run.

But in the light of the enormous drop in oil price since summer 2014, the warning in last year’s document was impressively well-timed: “Future energy costs are very difficult to forecast. Diesel fuel costs may in future rise faster than electricity costs, but the reverse is also possible. Electricity costs are currently rising to help pay for lower carbon sources. It is possible that the cost of fossil fuels used in generation may fall from their current high levels.”

So if there is no grand cascade plan… if the control of it lies in many different hands… if the pace and extent of future electrification remains in the hands of a future government that may have other priorities… how can the operational railway prepare for the next round of hand-to-mouth changes?

“There is no rocket science in this,” says Burleigh. “A successful cascade needs a lot of groundwork. It’s not just about the trains - it’s the training of the operators, training of the people who will train the fitters. It’s about having the depots and the stabling ready before the trains arrive.

“Moving from a diesel fleet to an EMU fleet brings practical challenges in terms of off-peak and overnight stables. In many cases this is not a trivial issue - replacing a two-car DMU with a three- or four-car EMU needs longer depot sheds and longer sidings. Large fleets being split means an appropriate allocation of spares, documentation, a different management of overhauls and maintenance schedules.

“And it means making sure the passenger-facing aspects are sorted long before the trains arrive. Has the recipient operator got the passenger information re-programmed? Has it made sure the booking systems reflect the seating layout, and maybe a different split between First and Standard Class than it had before?

“If these things are not done well, they can take a long time to overcome. Short-term issues and pressures can lead to some of these vital steps being rushed or omitted. Constantly moving fleets around is not a recipe for best performance.

“If you’re looking for long-term stability, the compatibility of the mix of rolling stock is key - stopping and inter-regional services have to work well alongside each other, especially if they share a depot. What happens with the electric suburban fleet running alongside IEP will be a good example.

“The franchise competition for Northern is now running. We’re the smallest rolling stock provider to Northern - we’ve invested in the incumbent fleet of ‘321s’ and ‘322s’. With our demonstrator we’ve created a new-train environment, and we are in discussions with anyone who may be interested. New trains may not be affordable there. There mustn’t be a perception about the North getting cast-offs. Quality is now a higher proportion of the DfT’s overall evaluation of bids.”

Burleigh points to the way Transport Scotland handled the recent ScotRail franchise (Abellio takes over from FirstGroup on April 1).

“We saw from Transport Scotland a very high requirement that any train moving across needs a good-quality interior, it needs to meet accessibility requirements, and it needs to be in the correct livery before it moves. All that was published in the Invitation To Tender.

“It spelled out by service groups the minimum functionality needed in terms of WiFi, power points, tables and air-conditioning. That was immensely helpful to us. There was a very comprehensive stakeholder consultation. It shared a draft ITT with all potential bidders and suppliers. That gave us an early chance to come up with more mature proposals.

“For example, when extra facilities are sought, the obvious thing to do is to combine that work with the existing heavy maintenance cycle - when the trains are out of service, anyway. The bigger fleets take three or four years to work through a heavy maintenance programme and you don’t want to take them out twice - the work needs to be done together so the trains can stay with the operator earning money.”

So is Transport Scotland’s refranchising a model for the Department for Transport to follow?

“It could be the model for the rest of the industry. We do know there has been dialogue. We really welcome it - it’s very helpful to us. We are keen to get early visibility of what the franchise objectives are going to be, so we can talk to our supply chain to commit to the pricing well before we deliver any enhancements, especially when they are needed very early in the franchise.

“From the Department for Transport perspective, it is beginning to work through into a more consistent system. There is a will to get into a more consultative regime where ourselves and others can influence the shape of future franchises.

“The franchising is becoming a two-year cycle. The first year is about consultation, so they get right what they want to buy before they embark on the competition phase.

“The bidders get a 120-day response time. But in that you have to take chunks off for scrutiny, review and approvals. If you’re not careful, bidders get very limited time to work up technical details and the pricing of fleet enhancements. That’s why we put a lot of effort into engaging with stakeholders even before an ITT is around in draft form.”

Third rail to overhead wires

In the current debate about how far and how fast electrification can proceed, Network Rail is evaluating the consequences of replacing the third rail DC system with overhead wires, although the sheer number of route miles and the intensity of operation means this is likely to become a longer-term goal.

Eversholt, which owns Southern’s huge fleet of Derby-built Electrostars, recognises clear benefits in terms of efficiency, resilience and capacity. But it warns that the practical challenges and costs of implementation are likely to push this down the agenda.

Getting from one state to the other (DC to AC current) may mean dual-voltage EMUs or modification of existing trains. The Electrostars were designed with conversion to AC built in, with space for pantographs and provision for running power cables through the carriages.

“Inevitably an operator’s horizon is only a few years long,” says Burleigh. “But we have to consider from the outset what we might need in the final years of that asset’s life. Dual-voltage operation clearly figured in that. The viability and commercial attractiveness of AC conversion will depend on how far ahead that decision is made. We’re not expecting it in the short term!”

It is now six years since anyone placed an order for a DMU. In that time, none of the old ones (however unloved) have been pensioned off because passengers need them.

Although electric trains are cheaper to operate, those lower bills alone do not offset the capital cost of electrification. The business case for putting up wires is a combination of cost reductions and the increased revenue that flows from more passengers attracted to modern trains (with the greater capacity they can offer and the wider socio-economic benefits that are so notoriously difficult to quantify, but which are widely accepted).

The industry says we need up to 19,000 electric vehicles over 30 years, but only 100 diesel units by 2043. No wonder the Rolling Stock Strategy says it is “probable there will be a business case” for further extending the life of diesel stock built under British Rail. It further states: “No new diesel vehicles would be required to be built in either CP5 or CP6.” So nothing until the 2020s. Though it predicts that up to half the old British Rail DMUs will be scrapped by 2024, it is likely that some old diesel trains – including HSTs - will still be in daily service when they are more than fifty years old. The motoring equivalent is what? An Austin Allegro? A Ford Cortina would be positively modern in comparison. This is a situation unthinkable in the car, bus or aviation industries.

The strategy estimates that a 50% increase in berthing capacity will be needed. Those old sidings have a future, while new depots will be required - especially in the West, North West and in Scotland, where demand for regional services is expected to rise faster than elsewhere.

And yet there is no formal plan for a cascade of rolling stock to fit this truly remarkable, unprecedented and geographically uneven growth scenario. The Government believes that the market will provide what the customer demands.

But today there is a shortage of rolling stock. DMUs are at a premium - there aren’t enough of them, and the wires are not yet ready to take the flow of second-hand electric services that will flow three years from now.

“I don’t see any evidence that DfT has acknowledged there is a problem,” says our senior rail industry executive. “It does not see that the solution lies at the centre. But that is the inevitable conclusion to get around the grief and cost that will follow.

“They’ve created a rail executive within the Department, under Peter Wilkinson and Claire Moriarty. There’s talk of spinning that out after a General Election and making it into an arrangement like the Highways Agency. The SRA got too big for it boots. But the HA is not too big for its boots - it’s just a centre of expertise. That’s what the Department for Transport desperately needs.

“It screwed up West Coast because the railways were being run by people who knew nothing about railways. That’s being corrected. The state getting involved is not something I would normally welcome, but in Wilkinson’s position I would take control, and be more centrally planned and interventionist about the cascade. The Department needs a joined-up long-term plan for rolling stock. Because currently it doesn’t exist.”

Peer review: Adrian Shooter

Peer review: Adrian Shooter

Chairman, Vivarail. Former Chairman & MD, Chiltern Railways

The origin of the confused situation that Paul Clifton describes can be traced directly back to the way in which the Railways Bill was put together in 1992.

I had a privileged position in that I was working for one of the BRB Members and was charged with helping to get some common sense into the proposals.

Unfortunately, the relationship between the Board and the Department had deteriorated to the extent that the civil servants tasked with drafting the Bill had been specifically instructed not to solicit any advice from BR. Much of their advice therefore came from lawyers - in particular aviation lawyers, because the notion existed that railways were conceptually very similar to airlines and that the best way to introduce competition (and thus break the ‘inefficient BR monopoly’) was to model the future of rail on the recently deregulated airline industry.

From time to time the drafters got stuck, at which point I, and a couple of other managers in similar positions, got a call that went something like this:

“You know that we are not allowed to talk to you, but do you fancy a coffee somewhere quiet?”

“Yes, if you are paying.…” was my answer. (I had no such instructions.)

At one of these sessions I became aware that train leasing companies were to be set up and sold off. They would be closely modelled on the international aircraft leasing companies for which the lawyers acted. There would be a totally free market in trains, which (like aircraft) would be completely portable and be deployed where the market dictated.

Deep breath…”in which case you should know that there are a few issues that you need to understand.”

I spent a fair amount of time explaining that while some trains are fairly “portable”, many are not for a variety of technical and commercial reasons. For example, a Class 321 EMU looks very similar to a Class 319, but you cannot use it on Thameslink.

Subsequently I was instructed to take a leading part in a small group within BR that created and prepared for sale the three ROSCOs. I hope that I succeeded in mitigating some of the wilder propositions that were being discussed.

It is worth remembering that the underlying assumption in rail privatisation was that railways were on their way out, and that much of the legislation was framed in a way that contemplated a gentle wider decline with a smaller and commercially viable core being defined and served by market forces.

There was absolutely no concept that railways contributed to the economic wellbeing of the country, other than a grudging acceptance that congestion in London might get a bit worse if there were no trains. Does this mindset result from the proponents all living within a cab ride of the City or Westminster?

This assumption was behind an insistence that train leases entered into by the pre-sale train operating units should have 15% of trains on short-term leases, the idea being that many of these short-lease trains would be returned to their lessors and that a genuine competitive rolling stock market would thus be created.

Having seen (from the inside) the many ways that BR wittingly or unwittingly drove passengers away, I could see that this would not happen. Equally unrealistic was the idea that the ROSCOs would initiate investment - it was always obvious that they would be owned by banks or bank-like institutions. And how often do you read about banks making speculative investments?

This was, of course, at the same time that the equally dotty idea was around that Railtrack would initiate enhancement investment.

It can be seen that the institutional framework set out in the Railways Act, containing as it did fundamental flaws, was going to set the scene for many problems in the event of (shock horror) railways becoming successful.

History teaches us that things tend to work rather better if civil servants concentrate on devising policy and leaving the delivery to a suitably incentivised private sector. The fairly frequent, often high-profile Government embarrassments can usually be traced back either to civil servants meddling in the detail, or their failing to have contracts which adequately describe to their private sector partners the outcomes they are looking for.

The privatised railway is full of such examples. Look at the recent Public Accounts Committee report on the DfT-led procurement of the Crossrail EMUs and IEPs, where the Department was heavily criticised for wasting huge amounts of public money.

Contrast this with several successful TOC-led train procurements which have resulted in fleets of excellent trains procured at very competitive prices and with very low procurement costs.

For example, South West Trains’ order for Siemens EMUs. Just to put this in context, this was the biggest train order Siemens had ever had, and the biggest order of any sort that the company had received for 20 years. Southern pulled off a similar trick with the acquisition of a fleet of Electrostars to replace its Mk 1 EMUs.

Virgin’s Pendolino fleet has (very cost effectively) transformed the West Coast Main Line, and the fleet of Voyagers has similarly changed CrossCountry out of all recognition. The fact that these Voyagers are now often very overcrowded on many routes is the result of a policy failure by the DfT, who (by their actions) made it impossible for any bidder for the current CrossCountry franchise to win if they included additional trains in their offer.

Anticipation of this type of problem was the reason for Chiltern lobbying in 1999 for a provision to be included in the ITT for the 20-year franchise that overcrowding must not exceed a set level. This has meant that Chiltern’s passenger satisfaction and growth has been much above average and has enabled the company to contribute substantially to the economic wellbeing of its hinterland. This benefit has far exceeded the theoretical risk the DfT perceived in underwriting “unnecessary” additional trains.

This provision explains why Chiltern has used its ingenuity to obtain small numbers of extra vehicles at frequent intervals. New Turbostar orders have been for as few as six cars, while the opportunity was taken to tag an order for eight Class 172 cars onto the back of an order for its sister company LOROL. It also explains why Chiltern has five rakes of Mk 3 locomotive-hauled coaches that it owns and why it did a deal with Porterbrook to acquire several Class 170 DMUs when their lease to First TransPennine Express comes to an end.

This latter has, of course, resulted in a degree of consternation in “the North” - a place far beyond a taxi ride from central London.

The moral of this story is that interested parties should lobby for all they are worth, to keep the DfT on the straight and narrow in that they should specify outcomes and not inputs, and that these outcomes should include a seat for everyone, except for very short journeys. Whatever happened to the ‘Boeing 737’ train? Well, there are nearly 500 of them - they are called Turbostars of Classes 168 , 170 and 171.

Peer review: Stephen Joseph

Peer review: Stephen Joseph

Chief Executive,

Campaign for Better Transport

Paul Clifton’s article exposes the fragmented way in which rolling stock is managed in the UK. Lip service is paid to having a market in new and existing trains, but in practice the DfT pulls the strings. The problem is that because it doesn’t want to be seen to be doing so, the bigger picture is missing.

And the bigger picture is about UK manufacturing and rebalancing the economy - something to which all politicians at least pay lip service.

If this means anything at all, it is about building up skilled manufacturing jobs in the UK, diversifying away from financial services. In particular, a focus on green and low-carbon industries ought naturally to include rail.

If this is to happen in rail, however, it will need Government leadership whereby it endorses and supports the industry’s long-term rolling stock strategy and uses franchising, funding and other levers at its disposal to produce a long-term order book for new and refurbished rolling stock, backed by the development of skills and apprenticeships to give these orders at least a chance of being made in the UK.

Government does do this in other sectors. It has an ‘automotive council’, grants, funding and regulation which together are promoting a move to low-carbon and electric cars being built in the UK.

Energy policy is more of a mess, given the reluctance of some elements of the Conservative party to admit that climate change is real and human-caused. But even here there has been support for various kinds of energy generation - for example, major offshore wind generation industries being sited in Hull and elsewhere.

The challenge is to make this happen for rail. As Paul’s article makes clear, the delays in electrification are leading to some short-term headaches whereby previous cascade plans will need revisiting, and which are dictating new diesels for Northern Rail, for example.

This on its own makes the case for Government leadership - the broader strategic economic case means that this must be more than short-term firefighting.

It will also have to bring in Transport Scotland, Transport for London and the emerging devolved rail operations such as Rail North.

Whether it is through a more strategic role for the Rail Executive, or through Labour’s ‘guiding mind’, the next Government needs to grasp this and make the long-term rolling stock strategy a reality rather than an aspiration.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.