Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

Rail passengers are no more aware of how their fares are constructed than motorists understand the detailed components that make one car insurance quotation cheaper than another.

Increasingly, travellers simply search for the most suitable compromise between convenience and cost and then fret that they have still missed out on the best deal.

But there again, nobody expects to understand the logic behind airline fares - they just accept that every ticket has a different price. So should it matter if the fares system on the railway follows a similar path? The convoluted, usually unfathomable fares system is a deterrent for passengers using rail. And the fragmented nature of franchising encourages increasing complexity whereby individual operators make more money by setting their own fares, at the expense of network-wide benefits.

“You’ve got to do something fundamental,” argues Jim Steer, founder and director of global consultancy Steer Davies Gleave. “Tear up the system that evolved over decades and start again. Start with the basic question: What is the purpose of the fare structure?”

Abolishing return fares would be the obvious route, switching to an airline system of one-way tickets that vary according to the day and time of travel, but this would work against the interests of train operators. So, there’s the inbuilt resistance to change.

Successive governments have considered it, but have shied away from tackling a structure that would be extraordinarily complex to dismantle, and potentially costly to reinvent.

Yet here’s the surprise: David Mapp, commercial director at the Association of Train Operating Companies, says: “Reform is a viable option. There is a strong case.”

The current fares structure was established under the Railways Act of 1993. Season tickets - reasonably priced under British Rail - were capped. So were long-distance Off-Peak Returns.

“A long time ago, Britain had a simple pence-per-mile system that was easy to understand. The further you went, the more it cost,” says Mike Hewitson, head of passenger issues at Passenger Focus.

“Demand management and commercial pricing really swept in during the 1980s, when the link between distance and price was broken.

“At privatisation, the Government tried to preserve network benefits in a fragmented system - the impression that there was a single set of fares like a national operator would have. It protected the ability - which we still value - of travelling on any train company’s services, not just the one from which you bought your ticket.”

That required a complicated process of lead and secondary operators, with the lead operator setting the prices for all trains. A secondary operator could set prices for tickets valid only on its own trains. If that seemed unfair to the lead operator, it could then introduce fares valid only on its own trains. It was a proliferation of choice.

“This certainly introduced some cheaper fares,” says Hewitson. “But it also complicated the system.”

Take Brighton to London as an example. There were two operators. Six per cent of the revenue went to the ticket retailer, and the rest went into a central pot, divided between the two companies using an algorithm based on the likelihood of which train the passenger would catch. The one that ran the most trains received the bigger cut, irrespective of which train the fare payer used.

If a third company set up, running just one train, it would get a cut of that money, even if no one got on the train.

“In the early days it led to what were called ORCATS (Operational Research Computerised Allocation of Tickets to Services) raids, after the complex system of fare apportioning,” says Hewitson.

“Train companies would try to squeeze one of their services into someone else’s area, to hoover up a share of their income. That drove business patterns - not the most efficient use of the timetables or the genuine demand by passengers. It was all about trying to lock into revenue streams. Whenever you get railway companies thinking more about protecting income than making better use of the timetable, you’re not running the most effective railway.”

ORCATS spurred the growth in Advance fares, for which the train operator receives all the revenue barring the retailer’s cut. Companies saw that they could get merely part of the all-operator fare, or 94% of the cheaper Advance fare.

From a passenger perspective that meant new attractive offers. But it also made flexibility more expensive.

“The result today is that one of the great advantages of the railway is under real threat - the ability to just turn up and go,” says Hewitson.

“People are not going to book a day at the seaside six weeks in advance - they’re going to poke a head out of the window the night before to check the weather. Heading towards more Advance fares changes the nature of rail travel.”

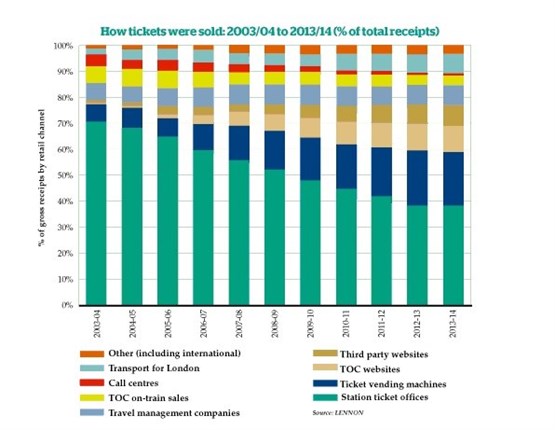

Today, there are varieties of tickets on smartcards, mobile phones, third-party websites, sent by post, or collected from competing operators’ ticket machines at the same station. We have complicated the act of purchase, as well as making the tickets themselves bewildering.

“If you ask people whether they want more choice, they will say yes,” says Hewitson. “If you ask them whether they want a simpler system that is easy to use, they will say yes to that as well. How do you square that circle?”

There are now three generic types of ticket: Anytime, Off-Peak and Advance. Every operator uses the same terminology.

On long-distance travel, the Off-Peak fare is regulated. Peak fares are unregulated. People generally make these journeys relatively seldom - the typical inter-city passenger makes a handful of premeditated journeys a year.

On short-distance travel, the Peak fare is regulated. Off-Peak fares are unregulated. Travellers make shorter journeys relatively often - every day, every week, every month. They often travel at short notice, expecting flexibility in ticketing.

Barry Doe, RAIL’s timetabling and fares expert, says that the current problems stem from the 1993 legislation’s decision to cap Off-Peak fares

“The train operators had to look at ways to improve their Off-Peak opportunity - the lion’s share of their revenue in most cases. So they abolished anything that was cheaper than the standard Off-Peak. But they were all tied into ORCATS. So whatever ticket was sold, each train operator was going to lose some of that revenue. Whatever Virgin took between London and Glasgow, 20% to 30% of it went to East Coast. And vice-versa.

“The only way out of that loss was to offer operator-specific fares. The train operator could offer a lower fare, but from which it could keep the entire revenue.”

Fares overload

The result: between London and Birmingham, there are, incredibly, now around 100 fares. Even on the 30-mile journey between Gatwick Airport and London there are 15 different single fares and this is impossibly confusing for first-time visitors to Britain.

“It doesn’t really offer the public anything useful,” says Doe. “It’s about pushing revenue the way of one particular operator. It’s just playing the system, perfectly legally. Plenty of booking clerks struggle to understand how it works.”

When the wide variety of Advance fares is added, Virgin has about ten different options between any two stations. That’s ten Standard, and ten First. The cheapest fare between London and Manchester is around £10 Single, rising to well over £200.

“If you turn up at a ticket machine, you can get dozens of options, all set out in railway jargon - a big mistake,” says Doe.

“And it isn’t in simple English either. For example, it assumes everyone knows what ‘Route not London’ means. If you did Salisbury to Brighton, would you guess that ‘Route not London’ means you could still do Salisbury to Clapham Junction and down? Of course you wouldn’t.”

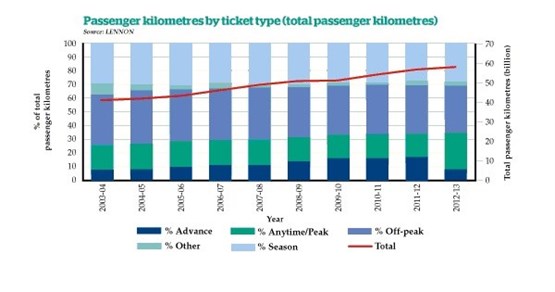

Advance fares make up a small proportion of the total. Most people still either buy season tickets or ‘turn up and go’ - nationally 50% are season tickets, 47% are walk-on fares and 3% are Advance. However, Doe says that on some trains from Euston perhaps half the tickets may be Advance, whereas from Woking to Waterloo there are none at all.

ATOC’s Mapp defends the way the system works: “We’ve actually had a common national fares structure since 2008. We have Advance, Super Off Peak, Off Peak and Anytime on long-distance; Off Peak and Anytime on short-distance. The Advance fares - the operator-specific fares - still conform to a common standard. We have pulled off a difficult balancing act - a consistent fare structure providing some opportunity for operators to set fares specific to their services.”

But is this good for business? Stephen Joseph, executive director of the Campaign for Better Transport, says: “If you are a national business - say the BBC or Sky - and you have offices all over the place, you get treated really badly by the railway. You have to negotiate with individual train operators for individual deals. You’re not given any frequent-user benefits. There are no discounts.

“Major businesses with corporate social responsibility policies want to use rail rather than road. But they find it very difficult. The railway is throwing away good business.”

Adds Doe: “Virgin came along with new Pendolinos - a massive investment - and was unable to put up its Off Peak fares to recoup the money. Off Peak fares must remain for evermore at the 1995 level plus whatever capped increase is permitted each year. Crazy commercially, but those are the rules.

“So with the Off Peak capped, the companies have all pushed up the Single peak fares - the only way they can charge the business account traveller. That’s why we’ve seen a 250% increase since privatisation - even accounting for inflation, that’s a doubling.

“It is a direct result of capping the wrong fares. They should have capped the most expensive fares.”

The result is confounding. The cheapest Advance fare from London to Manchester works out at 6p a mile. In the peak it rises to 87p a mile in Standard, 125p a mile in First.

Weymouth and Taunton are equal distance from London. Weymouth in the peak costs 42p a mile, Taunton is 79p. Yet South West Trains, despite charging almost half the price per mile, offers more frequent services on newer trains.

Meanwhile, the cost of putting petrol in the family car is around 13p a mile. Even adding in all the other motoring costs, for the majority of journeys, going by road is cheaper than a walk-on long-distance rail fare.

“The industry goes at the pace of the slowest,” says Joseph. “To get any change across the network, all the train operators have to sign up for it. Their incentive is always to do operator-specific ticketing because the operator sees more of the revenue. So the incentive is always to preserve - and further complicate - the system. The result is that fairness often plays no part in the pricing structure.

“Only the Government can take a view on this, because only the Government holds the total profit-and-loss account. If you wanted to buy out the system oddities, some operators would lose out. The losers would shout loudly. So nobody picks up on the benefits of simplification driving growth.”

Rip it up and start again?

“There has been no serious attempt to modernise the way fares are levied in this country since the 1980s,” says Jim Steer.

“The system is far behind today’s needs. The complexity acts as a deterrent to using rail. It loses a huge proportion of people and therefore loses revenue.”

Mark Smith, otherwise known as online consultant The Man in Seat 61, says: “The really major fly in the ointment is that Off Peak Returns are only £1 more than the equivalent Single. This idea was inherited from British Rail at a time when it made sense commercially. It is now fossilised by fares regulation. The Off Peak Return is regulated, so it cannot be increased. And the Off Peak Single cannot be decreased without significant revenue loss.”

Doe agrees: “The first thing I’d do is abolish long-distance Returns. We need a structure where a Single is the only fare you can get. Not today’s Singles, but half today’s Returns. So you’d get a cheap early Single, a higher Single in the peak, a lower Single again after 1000. How easy would it be then? You get the fare on the machine relevant to the time of day.”

But here’s the element of surprise… the Association of Train Operating Companies agrees (more or less) with all of that.

Mapp acknowledges: “Reform is a viable option. Potentially having only Single fares on long-distance, allowing passengers to mix and match to suit their own travel needs, is an interesting way forward. It is simpler to understand and provides greater flexibility. On short-distance we are likely to continue with Return for the foreseeable future because there is strong demand.”

Smith gives an example of why the current system confuses passengers. “You make a journey on a Friday, coming back on Sunday. A decision to use an Off Peak on your Sunday night return, because you don’t know exactly what time you will be coming back, not only affects your choice of fare on the Friday outward leg (you might as well pay the extra £1 and get an Off Peak Return), but also your choice of train.

Reform and revenue implications

“You now have to shift your departure to the 1900 train (the first Off Peak departure after the Peak), rather than the 1700 or 1800 you actually wanted, even if cheap Advance fares are available on them. That explains why the 1900 goes out loaded to the gunwales, while the 1700 and 1800 go out with lots of empty seats.

Doe warns: “Reform has huge revenue implications. A Single from Andover to London is only £2 cheaper than the Return Off Peak. Which is obviously daft.

“South West Trains tells me it couldn’t just be half today’s Return, it would have to be slightly higher. But at least then everybody could mix and match. You would simply pay the appropriate fare on the way back. It would be a lot more flexible.”

Steer thinks a zonal structure is worth considering. He recalls the Ken Livingstone-era GLC in London, when London Transport went to a two-zone system.

“This was the birth of the Travelcard,” he says. “Underground and rail, and later bus. The increase in use of public transport was massive. Delivered partly by simplicity and partly by not paying every time you got on and off.”

Mapp is less supportive of the idea, while not dismissing it out of hand: “What Jim suggests is there already in London. It is not a complete solution, but it might make long-distance fares less complex. There is merit in further consideration.

“At the moment we have to offer a through fare from every station to every other station. And the mechanisms we have to do that are quite complicated. Some form of zonal pricing, or hub-and-spoke pricing, might simplify that.”

So if everyone favours scrapping Return fares in favour of Singles only (and we haven’t identified a single dissenter), can it happen?

Doe gives the short answer: “No. The current legislation would prevent it. Ministers want it, but how do you do it? The law enshrines the current practice, capped at today’s levels.”

“The Department for Transport will not relax fares regulation to get rid of this anomaly, as the media would portray it as a sell-out,” believes Smith.

“But if it could be solved, in theory you would get just three choices outbound and three choices back, which could then be clearly and unambiguously displayed online: Anytime, Off-Peak and Advance on each specific train.

“At the moment we are handing passengers a quadratic equation to solve every time they travel. The DfT needs to bite the bullet. It needs to throw some extra subsidy at this.”

“I think the Department for Transport wants change,” suggests PF’s Hewitson. “It did a consultation last year. But if it loses them money the train operators won’t want it, unless the Government underwrites it.”

The DfT declined our interview request. Instead, a spokesman offered a statement: “We recognise passengers are concerned about the cost and complexity of fares. Following a ticketing review in 2013 we set out our vision for simplifying the process. This includes removing the fares flex for 2015. We will also run a trial with a scheme to regulate long-distance Off Peak single tickets, and remove the confusing situation where some single tickets cost nearly as much as return tickets.”

A train operator to conduct the trial during 2015 has been chosen, but at the time of writing has not been announced. ATOC’s Mapp is strongly supportive, but warns: “Ripping up the system is not something you can achieve easily - it means significant change to industry systems and retailing practices, with financial implications for Government.

“But if you are suggesting that some elements of rail pricing that have remained untouched since privatisation now need to be reconsidered, I think we would support that. We would not jump to the conclusion that everything has to be torn up. But if you suggest a more fundamental review is needed, we would not be unsupportive.”

Where would this leave the practice of split ticketing?

“Split ticketing is the elephant in the room,” says Hewitson. “It damages trust in the railway. It shouldn’t be down to the individual to know how the system works to get the best deal.”

Adds Steer: “It is completely pointless. It is a huge loophole caused by a system set by individual operators, which creates massive anomalies. We have to strip it out.”

Doe comments: “If I asked a ticket clerk for the cheapest fare, I’m likely to be offered the cheapest through fare, which may not be the same thing at all. But if I asked for all the different permutations to uncover the genuinely lowest fare, the queue would soon be backing up out of the door.”

Hewitson adds: “The classic one is on the Great Western. If you’re going to Cardiff but you change tickets at Didcot, you can save a lot. Didcot was in the pre-privatisation London & South East area, and ended up with a different pricing structure.

“If you’re in the know you can get a good deal. But how does a business engender trust if its customers are not sure they have been sold the right thing?”

Several websites now specialise in split ticketing. Passengers could use www.splityourticket.co.uk, www.splitmyfare.co.uk, www.faresaver.org, www.splitticketing.com, www.moneysavingexpert.com or download the Ticketysplit app.

“Some of the websites really do work,” says Doe. “But it brings the railway into disrepute. People who understand split ticketing can pay less than people who don’t know how to manipulate the system. It is not fair.

“East Coast tried to iron out split ticketing by using the element of “flex” allowed under the annual increase in capped fares. But now the Government has abolished flex. Passengers rightly saw it as a ruse by train operators to shove up the costs on the most profitable parts of a route. But the side-effect is that it locks in the benefits of split ticketing.”

Mapp explains: “Split ticketing is unique to the British market because of its combination of market pricing and regulation. It exists because of the difference between the way train companies price long and short-distance travel. That would be fine if short-distance tickets only worked on short distance journeys, but because the regulations require them to be inter-available, it creates split ticketing. It is an unintended consequence.

“It has been there since the 1970s. The only reason it has now become more commonly understood is because technology has made it easier for people to calculate split ticket combinations.

“Our view is that it is extremely confusing for customers. We cannot really have a national industry with its fares policy determined by fares anomalies. It has to come back to the common sense approach that fares are set at the level that the market will bear.”

Steer argues that only Government can clear this up. And unless change is imposed, he says, it will never happen.

“The more you take away the right of individual franchises to set fares, the more you diminish their ability to pursue the private sector theme of maximising returns to shareholders. Eliminating the annual flex has put a further constraint on them.

“Operators have all kinds of choices and in the current system they are essential. Change that, and the nature of franchising would take a further nudge towards them becoming concessions instead of franchises. They would be running trains within an agreed fare network.”

In 2013, Transport Scotland changed its ticketing structure to get rid of split ticketing and bought out some of the anomalies. It promised to recompense ScotRail for potential loss of revenue, which enabled it to take away 1,500 of the main splits.

“It comes at a cost - they are sometimes selling a cheaper ticket than before,” says PF’s Hewitson. “But in return it boosted trust and confidence. People don’t like buying a ticket and then finding the person in the next seat has bought the same thing for less.”

Transport Scotland said it meant cheaper fares for 275,000 journeys and that one end-to-end ticket would almost always be at least 50p cheaper than two separate tickets for the same journey.

Launching it, Scottish Transport Minister Keith Brown said: “Passengers had to navigate their way through a database. That’s not what we want. We want a fares system that is quick and easy to use.”

CBT’s Joseph says: “The proof lies in London. When national rail was added to the Oyster card, Transport for London had to make all sorts of guarantees that revenue losses would be underwritten.

“The operators had confidently predicted they would lose money. But national rail saw revenue growth of 8% in a year. Simplifying the system made more people in London want to use public transport.

“That doesn’t get picked up in the DfT appraisal system because it isn’t shaped to recognise network growth benefits. Simple offers to people matter and so far Government has made a complete hash of it.”

Joseph suggests a regional zonal card could make sense in Bristol, where funding for a metro system is now in place, with bulldozers lining up to work. He says it would now be unimaginable to have a city-based regional metro without one.

“I think the rail industry’s current stance is going to be overwhelmed, actually. I think it will just have to do this stuff.”

Could this be part of the ticketing review being carried out by the Office of Rail Regulation? It issued a consultation document in October, with a report due next summer.

Ann Eggington, head of competition and consumer policy, says: “We are trying to establish whether there is sufficient incentive on train operators to collaborate for the benefit of consumers. Or is the governance itself dampening the process, because of the processes attached to them? For example, why do we still have paper tickets, and why do we still have problems with ticket machines?”

Steer is dismissive: “ORR will just tamper with it. The system will get even more complex without tackling the underlying problem. Someone has to admit that the system is broken and order it to be fixed. I don’t see that happening at the moment.

“Politicians have to feel there is sufficient benefit in doing it. But they shy away from it. I can’t understand what is unappealing about it, apart from the effort it will take to achieve.”

How do other countries tackle the walk-on versus pre-booked question?

The ‘go-to’ person for European advice is The Man in Seat 61. Mark Smith runs a website (www.seat61.com) to guide international rail travellers and he knows his onions - a former customer relations manager for train operators, he then went to the Office of the Rail Regulator and then the Strategic Rail Authority, ending up at the Department for Transport running the team regulating fares.

“In the UK we have a more commercially aggressive system. We have cheaper advance fares than other European countries and we have much more expensive full-flex long-distance fares for business travel. The Europeans sat there with big government subsidies and no commercial imperative to increase revenue. They are following in our wake, but they are at least ten years behind us.”

Smith divides European long-distance ticketing systems into two groups: countries that operate a flexible walk-on long-distance system; and countries that operate airline-style booking in which every ticket comes with a seat reservation.

Spain, Italy and France operate like airlines, with every ticket for a single specific train. If you want to travel an hour earlier or later, you have to visit a ticket office to change your reservation.

Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Denmark and the Netherlands operate as the UK does, with open tickets that can be used on any train and with reservation an optional extra.

“The basic ethos with us is that you can get on any train,” says Smith. “We suffer overcrowding because on this system you will always get a mismatch between demand and available seats. You have a lower average load factor on UK trains - 40% - because it’s a walk-up railway.

“Some people say you should be guaranteed a seat on a train. Be careful what you wish for: the only way to do that is to switch to the French or Spanish model where every ticket has a reservation, where you can’t just hop on a later train.

“Virgin and East Coast have invested in airline-style yield management technology. So the reservation system could handle the varying of prices if the change was wanted. But in the UK the fully flexible ticket is seen as a key advantage of travelling by train, and I don’t think we would want to change that.”

Smartcards offer a solution, according to Hewitson at Passenger Focus. “When you click in and click out, the system knows whose train you are on, where and at what time, and sends all the money to that operator,” he says. “That could lead to companies competing for customers on the basis of good service, clean toilets, no rubbish on the seats, or a loyalty reward for regular travellers.”

The evolution of smartcards on the railway is far behind the bus industry… and far behind the expectations of passengers, politicians and operators alike.

“The South East Fast Ticketing Initiative (SEFT) has been so slow,” complains CBT’s Joseph. “The Department has spent years not delivering it. Government doesn’t like taking leads on IT initiatives - its record is pretty terrible.”

SEFT was set up in 2011 with £45 million of Government money, much of which remains unspent. Across most of the capital, commuters still get nothing more than a paper season ticket with a magnetic stripe, which often fails within a few weeks - leaving premium customers queuing slowly at the manual ticket gate, the last to leave the platform.

“Oyster came in because a few key people had a vision and made it happen,” says Hewitson. “Smartcards did not have the same grip, the same dynamic leadership. It was held up by 20 train companies, sitting around a table wondering what to do.

“If you have a ten-year franchise, it takes most of that time to set up a smartcard system and costs a lot. So unless the Government writes it in as a franchise commitment, it’s not going to happen - there simply isn’t enough payback time.”

Passenger Focus thinks national rail travellers will take longer to trust a plastic card system than Tube travellers did with Oyster. If you’re commuting for an hour, will you accept that a simple tap in and tap out has charged the right amount? With Oyster the cost of getting a fare wrong is only a few pounds; on a main line railway it could turn the bank balance red.

Yet smartcards could also bring a range of payments for a part-time commuter - those who travel three days a week could see a real benefit.

“We’ve been talking with Government about flexible part-time ticketing,” says Joseph. “They’ve found this very difficult. We were told there would be smart carnet tickets across the South East. Then some of the train operators objected and the idea has gone backwards. I think the Government would have to compensate train operators, even though we all know smart ticketing will quickly drive more business their way. The Government finds that a hard sell.”

“Smart tickets will also enable Rail Miles,” adds Hewitson. “Air Miles work really well as a reward system. They could lead to a free cup of coffee every so often - this could mark the shift from being a simple utility provider, moving a person from being a passenger to a customer. You can do the occasional freebie if the operator knows who you are, where you travel and how often.”

Steer believes smart ticketing will bring massive savings for the industry. In particular, he points to the ability to get new organisations selling tickets - with fares reform, they would not have to engage with the complexities of the current system.

“The holy grail with smart ticketing is tailoring products to individual customers,” he argues. “They can find the person who wants to travel First Class, paying extra for premium car parking. You could also offer free or deeply discounted travel for people going to job interviews - these things are much easier if you are overlaying them on a simpler fares structure. The social value approach to fares goes hand in hand with a simpler system.

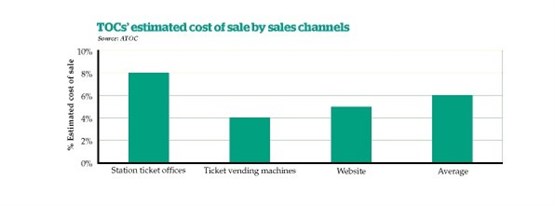

“It needs a Government which will reduce the cost of retailing. We could take 5% out of the cost of running the railway - all the companies want to close ticket offices. But as things stand they can’t. We need to remove a very inefficient and archaic system.”

Go-Ahead Group’s Southern Railway has taken the lead here. Since the autumn, it has been possible to get on a bus in Brighton, then the train to London, onto the Tube, and to finally catch another bus - all on the same piece of plastic. It works from Bognor Regis to Bethnal Green, or from Eastbourne to Ealing Broadway.

For that to happen, 20,000 gates and readers have been updated, led by Cubic Transportation Systems. Riz Wahid, head of retail at Go-Ahead, has worked on the project since 2009.

“KeyGo is the next step: our version of pay-as-you-go. It’s currently working outside London. I’m in discussions with Transport for London to get our version working inside the capital as well.

“As you register your Key, you also register a bank card against your account. So if you tap in at Brighton and tap out at Lewes, we look at the route you’ve travelled, any entitlements you may have, at Singles and Returns, and all the tap data. This enables us to charge for the cheapest journey you made at that time.”

That requires a 100% reliable system that the passenger can trust, and the low take-up of The Key (the smartcard system of which KeyGo is part) suggests it isn’t there yet - currently only 250 customers use KeyGo in Brighton and Crawley. Changing passengers’ habits (Wahid calls it “migrating them over”) is not happening fast.

“I have a team of engagement managers working on it,” he says. “What we don’t have is a price difference between paper and plastic. The fares are the same. We need to make offers that are plastic-only to bring change. That’s something we’re working on with DfT, but it means changing fares regulation.”

“Go-Ahead’s efforts deserves credit, says Joseph. “It put the work in, to make The Key interact with Oyster. Go-Ahead did not strictly have to do that. I’ve been told by National Express that the work done by Go-Ahead greatly eases their task on Essex Thameside. Go-Ahead went through hundreds of iterations to iron out bugs in the system - so others won’t need to.”

Essex Thameside is planning to run its own smartcards, but in principle The Key could work outside the Go-Ahead franchises. Wahid says a franchise extension on Southeastern will include a commitment to extend The Key into Kent. It will also appear on the new Thameslink concession.

“There is no reason why we couldn’t agree with people like Stagecoach for our card to be accepted on their network,” he says. “They would get the same revenue as they would from a paper ticket. So there is no revenue risk to train operators at all.

“We just have to make sure those train companies have a device that works our cards. We had to do the work with TfL to make sure that if a customer turns up at (say) Islington with one of our cards, the staff there have a device that can read it - even if the staff have never seen The Key before.

“Technically that is relatively straightforward. It’s more about the commercial agreements and the training.”

But if others go their own way, such as Essex Thameside, won’t an already absurd variety of fares and ways to pay for them become insufferable? Wahid says he has given SEFT the Go-Ahead technology.

“There’s nothing stopping another operator coming up with its own version, but it would get very difficult, very confusing for the customer if we all have our own versions of the same thing.”

But why use a dedicated charge card? Surely a contactless bank card, which can be read throughout London, can do the same job. One card fits all?

TfL thinks it heralds a likely change in the way millions of Tube users pay for their journeys. But it won’t help children without bank accounts heading to school - there are many people for whom a plastic card such as The Key will remain essential if paper tickets are replaced.

Wahid concludes: “In a few years, I hope we will remove the complexities of customers going to self-service machines every day and remove the queues at ticket offices. We need customers to touch in, touch out, whatever their journey.”

So where does that leave us? More than 713 million passenger journeys were made in the six months to September 2014 - that’s a 3.7% increase on the same period last year, equivalent to more than 140,000 additional passengers a day, according to the Rail Delivery Group. The growth outstrips other European countries, with passenger numbers rising by 62% in the UK between 1997-98 and 2010-11. That compares with 33% in France, 16% in Germany and 6% in the Netherlands.

Does it all really matter?

So the increasing complexity of fares has arguably had no ill effect, despite our ticketing structure being a good deal less easy to understand than that of our European neighbours.

Our travel by train also costs more - from January the annual season ticket is expected to rise on average by 2.5%, which is nearly six times the average rise in wages.

The industry is confident passenger numbers will still grow… and keep on growing for the foreseeable future. Why bother with the costly complication and sheer hassle of developing a different fares structure if the existing one will keep the cash rolling in? There is no incentive to change.

This frankly ludicrous system works. Not efficiently. Not smoothly. Not cheaply.

Split ticketing has no place in a well-organised railway, because it serves no purpose.

A single fare that costs £1 less than a return fare makes no sense in a smartcard future.

And the paper ticket already abolished by airlines is an anachronism. Yet it is likely to continue for many years to come - quaint and perhaps quintessentially British, like wearing tweed in the rain in preference to the latest waterproof fabric.

But what if the fares system could be rebuilt as well? Everybody interviewed for this article thinks it should change. Almost everybody interviewed also thinks it won’t change.

Yet ATOC’s comments here are genuinely new. The train operators themselves are open to the idea of sweeping away the regulated Off Peak Return and having airline-style single-leg journeys instead. The Department for Transport will organise a trial. The barriers to change have not yet been removed, but they are no longer padlocked in place.

Nobody designing a new fares structure would come up with anything close to what we have today. In the fragmented passenger railway, there are 20 different pricing managers inevitably seeking to manipulate the system in 20 different ways. But fares regulation keeps things together - more or less.

But because passenger numbers will continue to grow regardless, there are many reasons not to pick what almost everyone thinks is The Right Thing To Do: tear up the system and start again.

Peer review: Guy Anker

Peer review: Guy Anker

Managing Editor, Moneysavingexpert.com

Trying to understand the complexities of the rail fares system can seem about as easy as trying to understand Einstein’s theory of relativity.

OK, so the rail system may not quite get your head into the same sort of twist as trying to understand the space-time continuum, but Einstein would still have had plenty of material to work his magic on, had he analysed train travel.

The piece de resistance and the master of all counter-logic is split ticketing. But I’ll come onto this and the many other barmy practices later.

Paul Clifton’s article largely hits the nail on the head in the way it goes through the catalogue of complexity that may flummox all but the keenest train-spotter, although I would question whether all the suggestions put forward would really work.

I must point out that I come at this debate from a commuter’s perspective - my job when writing about train travel is trying to find the cheapest way for passengers to purchase a ticket.

But here are the key problems as I see them:

- Split ticketing is quite possibly the most illogical of all ticketing systems.

Put simply, split ticketing shouldn’t work. It makes no sense. And yet it does work on hundreds of routes and the savings can be enormous. We’ve built an app to help people find cheaper tickets this way, as otherwise it can be an arduous trial and error exercise.

Jim Steer suggests that split ticketing should be outlawed. That would be a shame if it meant those who benefit from split ticketing end up paying more, but if it brings simplicity to the market and means that people save overall, it will be beneficial.

- Returns can only cost a few pennies more than singles, but two singles sometimes beat a return

We often tell our users not only to check the price of a return, but also the price of two singles, given that on one trip the first method can win, but on another the second method will triumph. How is this inconsistency helpful?

In the article, Barry Doe suggests a structure whereby singles are the only option, but only singles at half the current return prices (I presume he means where it is currently cheaper to buy a return over two singles).

This would be a wonderful simplification of the system, were it to happen. But I will throw in a note of caution - we’ve seen it in other industries where a new structure is announced and companies agree initially to adopt the lower price, but when the spotlight is no longer on them, they revert to the higher price.

It’s like when airlines first offered reductions for not checking in luggage, as if it were a discount. Now the base fare without luggage is the norm and you pay more to check in luggage.

The risk with trains is operators ‘jimmying’ the system, so where a return is currently cheaper than two singles, the operators double the price of existing singles to make them more expensive than return fares.

- There are so many different fares, it’s difficult to benchmark a good price

I know that if Tesco sells my favourite can of tuna for £1 I’m getting a good deal, but if it’s £2 then I’ll look elsewhere as I know I’m being overcharged. If I buy a train ticket from London to Newcastle, then I’ve no idea what is a good price and what is too expensive, as there are so many possible prices to pay.

I’ve only just learned from reading Paul Clifton’s article that there are 100 fares from London to Birmingham, which is incredible and makes it impossible for a commuter to know if they are getting a good deal much of the time.

I also like the article’s analogy that understanding different fares is like trying to understand how car insurance premiums are calculated.

- You pay the same price for a slow or fast train

If I go to a football match, I expect to pay more for a seat high up on the halfway line than in row one behind the goal, as I get a better experience.

Yet I pay the same price on the fast train from London to Brighton, which gets me there in less than an hour, as I do on the one that stops at what feels like every station in the galaxy and gets me there after the last bus has departed. Surely there should be a discount to get the slower train?

- First Class can cost less than Standard Class

This is rare, but is possible. Even when First Class is only slightly more expensive, it can be cheaper overall to buy it as it can save you having to pay for food or WiFi access on-board.

It’s wonderful for those who benefit from cheap First Class fares, and we always tell people to check the price of First Class, just in case. But it really makes no sense whatsoever.

n People often prefer simplicity over price

We ran a poll on the energy market a couple of years ago, asking our users if simple or cheap tariffs are more important to them.

A decent proportion - 37% - said they’d accept simpler tariffs even if it meant some cheaper deals rise in price.

Let me be clear that I do not want to see already high rail prices (which sometimes cost more than a plane ticket) rise even further. But there is no doubt that people want simplicity in any market.

Peer review: Managing Director of a TOC

Encouragingly, there is broad consensus among different industry parties about the ‘complicated muddle’ that is the current fares system - and (more importantly) about the potential way forward. Disappointingly, however, the quietest voice in the debate belongs to the Department for Transport, the organisation actually with the responsibility and authority to tackle the issues holding back much-needed simplification!

Within the debate it’s important to recognise the varied nature of the markets that rail serves, from high-volume urban services to long-distance inter-urban services. The needs of these markets and their competitive environment are very different, and rail fares need to reflect this to ensure the long-term future of the railway.

One size does not fit all. In reality, there will always be anomalies where these markets interact, and we need to work hard as an industry to ensure that these anomalies are minimised.

The move to market-based pricing from pence per mile pricing led in reality to a reduction in fares on many flows. It recognised the more competitive nature of certain markets – particularly long-distance, where air and road competition exists. Reverting to a pence per mile basis would likely see fares increase.

The point about Advance Purchase (AP) fares being used to manipulate ORCATS is fundamentally misleading. The majority of tickets are sold on flows where one TOC receives the overwhelming majority of revenue from inter-available tickets. The development of AP fares has been used to spread loads more effectively across trains, minimising crowding and offering cheaper fares to passengers travelling at less attractive times.

The article is vague on the difference between operator-specific fares and AP fares. The former are not the same as the latter. AP fares are train-specific, and it is sensible that revenue from those tickets goes to the operator that carries the passengers. Operator-specific fares are often walk-up fares that limit travel to any of the trains of a specific operator.

Barry Doe’s view that operator-specific fares are cheaper but do not offer anything meaningful to the passenger is open to challenge - a cheaper fare is something meaningful, given that the price paid for tickets is one of the biggest issues for passengers in the National Rail Passenger Survey. However, the reduction in price does come with an overall loss in flexibility to the passenger.

The value of flexibility really needs to be considered in more detail. Providing for flexibility comes at significant cost and with a considerable waste of resource. How we balance these two conflicting aims needs careful consideration.

The industry and technology has changed significantly over the past 20 years. But what hasn’t changed in that time is fares regulation, which was set in stone at privatisation and has evolved little since.

So the fundamental question needs to be asked: “What is regulation for?” Until that question is answered, the right path for reform cannot be determined. Frequent government intervention (code for an interminable series of fares and ticketing reviews) has delivered little owing to two primary drivers: political fall-out and financial implications.

Where pressure really needs to be applied is at ministerial level - that is the key obstacle to improvement and change.

Peer review: Tim Shoveller

Peer review: Tim Shoveller

Managing Director, South West Railway

The perception that fares are complex and too expensive has become one of our railway’s key determinants of reputation and trust.

Perhaps this is most acute for potential passengers who may see this as a barrier to ‘trying the train’, or (worse) misunderstand the complexity and believe that the railway is deliberately obscure to satisfy a profit motive. This is not the case, and it is not the way we wish to be perceived.

Paul does a great job in bringing together some key elements of the debate. He highlights why the problem is so very complex, with few solutions that do not have sometimes significant consequences - even if there was political will to support the industry through a very difficult change.

The equally difficult issue of how to respond to passengers who do not comply with the conditions of their ticket adds further emotion and complexity to the position.

So, what to do? Perhaps we need to be clear ourselves about what we want from our fares structure.

While the existing arrangements are not perfect, we can at least understand if any of the alternatives actually result in an overall improvement - or just a lot of pain to move the problem around while creating new issues.

For example, I believe that further evolving the fares structure to ensure that we maximise the capacity of our railway is an essential area of focus - not least to ensure that we offer the best travelling environment to as many passengers as possible.

As making physical interventions to increase capacity become harder and much more expensive (as we complete the ‘easy wins’ to lengthen trains/increase paths), we will have to be much more careful in our use of capacity.

The current arrangements on some of our busiest railways are a rather blunt instrument and do not really manage capacity and yield very well. Contrast this with the more complex position on longer-distance, former Intercity flows, where the huge increase in Advance ticket sales has served to allow a successful degree of yield management while still smoothing capacity peaks.

For long-distance flows, it is not difficult to see how this principle could be taken further so that no passenger on an Intercity train should have to stand (that would be a fantastic achievement). But does the potential loss of flexibility in restricting walk-up tickets have a greater disbenefit than offering every passenger a seat?

As London South East fares tend to be relatively simple, to better support a capacity-focused approach extending yield management to LSE railways would add complexity from the current position. But is this a bad thing?

Further, I think the debate becomes less relevant with the massive development in technology that is under way. We have to stop thinking of a fares structure in an extrapolated Edwardian/1970s model, which relies on a paper ticket without any means of communicating lots of essential information to passengers.

Tomorrow’s tickets will in some form be digital, which I believe creates many opportunities to achieve what we really need: revenue growth in an environment where our passengers feel that they have been able to make well-informed choices.

Peer review: Claire Perry

Peer review: Claire Perry

Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Transport

The UK’s railways are a real success story. More passengers than ever before are taking the train and we are responding to that demand by investing in the biggest rail improvement programme since Victorian times.

From the new Intercity Express trains that will roll out on the East Coast and Great Western routes from 2017, to a transformed franchising programme that this year alone has successfully delivered three major franchises in Essex Thameside, Thameslink and East Coast, passengers are already benefiting from more trains, more services and better journeys. And with more than £38 billion being invested in the network over the next five years, passengers can look forward to even more improvements.

Fares are crucial to funding this transformation of the rail network. But, as more and more people choose to travel by train, I am absolutely determined that we develop a modern, flexible fares system that meets their needs and expectations.

Much has been achieved since we published the conclusions to our Fares and Ticketing Review in 2013. This set out our vision for a modern and customer-focused fares system, and we have already delivered important changes for passengers.

Perhaps the most significant improvement is that, for two years running, we have imposed a real-terms freeze on regulated fares, capping them at RPI+0% for 2014 and 2015.

During 2015, train operating companies will also no longer be able to increase individual fares by up to 2% more than the permitted average increase. By preventing operators from raising fares by excessive amounts, we are protecting passengers from large rises at a time when family incomes are already being squeezed.

We are also rolling out smart ticketing, with the aim that by 2016, passengers in the South East will be able to use tickets on other forms of transport. This will also allow flexible ticketing products to be designed around the needs of the customer - as well as providing a model with the potential to be rolled out across the rest of the UK.

I am also keenly aware that the information given to passengers when they buy tickets from vending machines isn’t always good enough, and that this can prevent them from getting the best value fare for their journey.

I have asked the rail industry to look at this and it is clear to me that they are committed to making real improvements. It is of critical importance - both for passengers and for the reputation of the industry - that passengers are able to confidently select the most appropriate ticket for their journey and are helped to understand the terms for using it.

Work is also under way on possible future improvements. The Department will be running a trial to explore Single Leg Pricing, which could offer passengers increased choice, flexibility and opportunity for savings, while simplifying the confusing scenario of some single tickets costing nearly as much as a return.

Getting the fares and ticketing offer right is integral to our long-term economic plan of delivering a world-class railway.

As new tickets and technologies are developed, I want the Government to be at the forefront of making sure passengers get a great deal every time they travel.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.