Are we really getting value for money when building new stations? Mel Holley investigates.

In this article:

Are we really getting value for money when building new stations? Mel Holley investigates.

In this article:

- New station costs vary wildly, often due to public bodies' inexperience, excessive consultancy, and lack of standard designs.

- Projects like Soham and Kenilworth highlight overspending, poor integration, and unmet local aspirations.

- Rolling programmes, experienced leadership, and standardised station designs (as in Scotland) could reduce costs and improve outcomes.

The railway is getting too expensive… and privatisation is at fault. This is a political mantra quoted by those championing nationalisation, yet the costs of a new station vary widely.

But given that, almost without exception, recent new stations have been led by the public sector (generally local authorities), what’s gone wrong?

The answers are complex, but also simple. They also show that you don’t always get what you pay for…

Gold-plated standards

None of the stations that have opened in recent years (and we are concentrating here solely on all-new stations, not rebuilt ones) could claim to be ‘gold-plated’. In many cases they are functional, fit for purpose, and apparently designed to a price.

At least, that’s what you’d expect. From a passenger or operational perspective, there’s no ‘gold-plating’. But delve deeper, and hidden costs start to emerge.

Let’s start at the start point. What does ‘expensive’ look like, and what should be the ‘real’ cost of a new station?

As with any builder asked to quote for a house extension, there will be an intake of breath before you’re told: “It depends.”

RAIL spoke to many people in the course of our investigation - all off-the-record, as no one wished to be quoted. And common themes emerged.

Firstly, it depends what was on the site before. Like all projects, a ‘greenfield’ site is easier to develop as generally it’s reasonable to assume that there won’t be anything ‘nasty’ in the ground - unlike a ‘brownfield’ site that’s previously had structures on it.

Secondly, there’s the caveat about ground conditions (are piles required? Are there flooding issues?) and the usual environmental and planning surveys.

You’d expect that if a council is specifying the station (which they often are), these matters would be seamless. However, this requires a big leap of faith that the transport and planning departments are working closely together.

Thirdly (and here comes the ‘biggie’), it’s a railway project.

While Network Rail continues its focus on cost-control and efficiency, when it’s an ‘outside’ job for another body, contractors will automatically charge ‘full rate’. Or even, we are told, add extra pricing to cover the ‘hassle’ of working for ‘the railway’.

Surely, you’d think, there would be standards?

Indeed there are. Rail regulator the Office of Rail and Road (ORR) controls the specifications for the stations, such as the height and location of a platform relative to the track, and much more. These are all clearly set out in its published documents as Railway Group Standards.

Similarly, NR publishes a suite of strategic documents, two of which cover stations.

These are good starting points, but they come (perhaps) with inherent flaws reflecting that they were drawn up in the Prime Minister Boris Johnson era. In the phrase of the time, the words “world-class railway” are an occasional visitor.

Starting point

Calls for a new railway station tend to come from local communities (‘righting a historic wrong after their station closed’), or in response to new perceived demand from business/residential developments.

How do you work out how big your new station should be?

That’s outside the scope of this article, but note how the rapid and changing growth in London Docklands saw its light railway change considerably from its 1987 opening to the system it has become today.

In terms of stations, some have been rebuilt. Famously, Island Gardens was built, and then closed for a total rebuild before it even opened, because development had overtaken the original design.

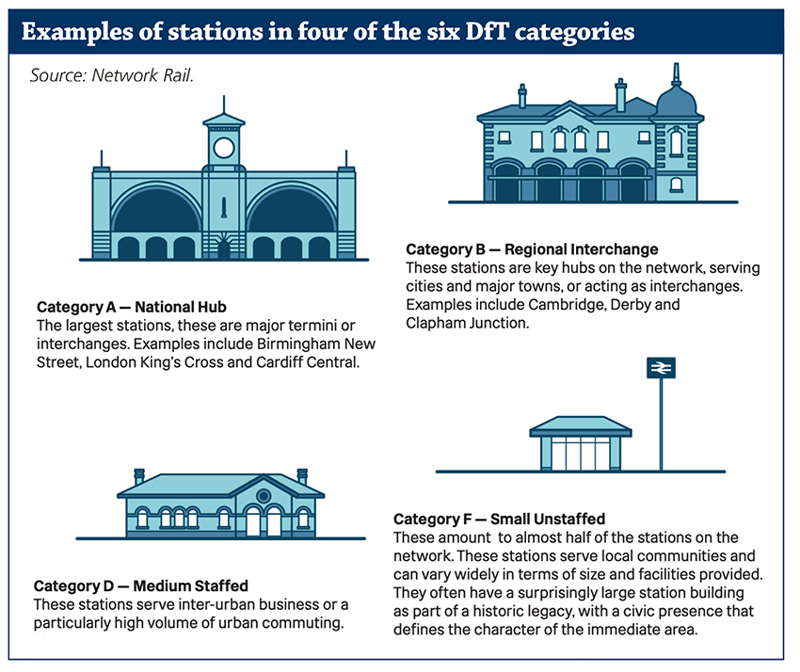

What sort of station you should build might seem obvious. But to guide councils and developers, Network Rail’s Station Capacity Planning design manual sets out the approach.

“It is important to have a consistent approach for sizing stations. This guidance is our baseline for minimum space provision,” writes NR Head of Station Capacity Planning Isabelle Milford, in the document’s foreword.

“But we ask everyone planning and designing stations to aim for an excellent passenger experience across the network. Clearly that sometimes means going beyond the minimum.”

The 107-page document goes on to explain the methods for calculating how much space will be needed for passengers - including in the concourse, waiting areas, stairs, passageways, ticket gates, and so on.

From all this information, formulas enable calculations for how many ticket gates are needed, provision of other services, the level of acceptable volumes of passengers, and ‘crowd dynamics’, in what’s known as Fruin’s Levels of Service.

It’s all good stuff, but unlikely to apply to a small wayside halt (unless it’s next to an events stadium or arena).

Next up is the Station Design Guidance, also from NR’s suite of Design Manuals.

In 108 pages, it offers “high-level guidance aimed at the sponsors, designers and planners of new railway stations”.

It outlines “not just the factors determining physical space within stations, but other components that need to be considered to achieve world-class station design”.

There is no argument that a well-designed station is a good asset, and the guidance is littered with pictures of the jewels in NR’s modernised stations crown - including those inherited from the Victorians, such as York, King’s Cross and Sheffield. Smaller stations, such as the platform canopies at Stamford (Lincolnshire), are also illustrated as an exemplar.

Again, it illustrates ‘best practice’ with a view to making stations attractive as well as functional.

Yet it tends to concentrate on medium to large stations, and doesn’t deal with the issue of small stations - the ones that are most-often proposed and built.

These are the ones that also suffer from the challenges of providing access to platforms, entailing lengthy ramps connected to footbridges.

Some recent station reopenings have been part of wider schemes, and thus it has proved impossible to tease out their costs.

The largest ongoing project of this nature is the Northumberland Line, with a final estimated cost of £298.5 million.

This project involves rebuilding a former freight line and the creation of six new stations. It is a collaboration between Northumberland County Council, the Department for Transport, Network Rail, and the DfT’s Northern Trains.

An initial passenger service started on December 15 2024. Three stations (Ashington, Seaton Delaval and Newsham) have since opened, with Bedlington, Blyth Bebside and Northumberland Park to follow later this year.

On a value-for-money basis, Scotland currently has more feathers in its cap.

The opening of the Levenmouth rail link shows what can be achieved. It’s been a complete strip-out and rebuild of a five-mile former freight line, joining the Fife Circle Line at Thornton North Junction.

Promoted by Fife Council and the South East Scotland Transport Partnership, it was approved by the Scottish government on August 8 2019 and opened on May 29 2024. It delivers two stations and total track renewal (includes 11.8 miles of track) for £116.6m.

At the other end of the scale is Soham (Cambridgeshire), where a single four-car platform, with no passenger facilities, cost a staggering £18.6m.

Despite many questions, no explanation has ever been forthcoming for why that cost was so huge. It does include a footbridge (steps only, no ramps) over the line into a muddy field, allowing an adjacent foot crossing to be closed, but which doesn’t actually serve the station itself - but otherwise that’s it.

By any measure, Soham is Britain’s most expensive platform to date. Funded by Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority (CPCA) and Cambridgeshire County Council, it fulfils a long-requested campaign by locals and is served by the two-hourly Peterborough-Ipswich service run by Greater Anglia.

What do you get?

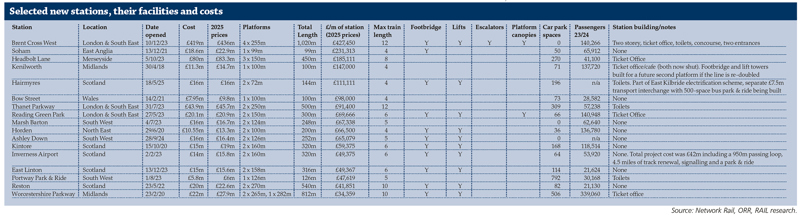

Ignoring major schemes such as the Levenmouth, Northumberland and Crossrail lines, and instead focusing on ‘infill’ schemes, there’s a wide variety of new station costs.

In an attempt to drill down into what the cost should be, the accompanying table (pages 26-27) provides some vital statistics, with prices adjusted for inflation to 2025 numbers.

Given that building platforms is expensive, and that every station must have at least one, this seems like a good yardstick. Therefore, the table is ranked by costs per platform metre, which we’ve created by simple maths, dividing the total cost of the station by the total length of its platforms.

The longer the platform, the more signs, fencing, walling, lighting, drainage and public address systems (and so on) are needed.

There will also be local considerations, although awkward-to-access sites (such as in deep narrow cuttings or on tall embankments) rarely make it through the initial outline business case, owing to the extra civils works.

Clearly, not only has there been real inflation since pre-2019 (when many of the schemes were planned and costed), there has also been some actual price inflation, even when you compare the facilities offered.

Top of the table is Brent Cross West (£427,450 per metre).

This is no modest country halt, this is a full-blown city station with four platforms and capacity to match, so is ‘voided’ from our analysis.

But it is included for comparison, as it’s going to be a handy reference when the equally impressive Cambridge South opens early in 2026. Like Brent Cross West, it won’t have a car park, but it will have four platforms and is currently estimated at £211m - so a bargain, perhaps?

Next up is Soham - at £231,313 per metre, when other similar stations come in at under £100,000 per metre.

If you want ‘basic’, then Portway Park & Ride (near Bristol) is exactly that. A platform, lights, and… a bit of fencing. It comes in at a miserly £47,61 per metre.

Cheaper still, bearing in mind that it has a footbridge and lifts, is Reston, on the East Coast Main Line in Scotland. Once again, it proves that ScotRail’s grip on costs is fierce and that if you want an example of what ‘good’ looks like, it’s Bill Reeve’s railway (Director of Rail at Transport Scotland) that you need to visit.

There is one anomaly: Worcestershire Parkway. This is on a penny-pinching £34,359 per metre, yet it’s almost a ‘full-service’ railway station. It was delivered late and more expensive than the original early (optimistic) proposed budget, but it does seem to be good value.

Perhaps some liquidated damages from the delays have been rolled in, which is why £22m bought so much in 2020? Again, we’ve asked, but answers were not forthcoming.

Just look at its numbers: In 2020 a three-platform station, with ticket office and car parking, was built for £22m. The end of the following year saw £18.6m spent at Soham on a single platform with only a ticket machine and two halves of a bus shelter.

We have to offer an answer to the question: ‘how much should a station cost?’

It’s a crude measure, but taking an average of the ten ‘reasonably priced simple’ stations in the table suggests that for something modest (including the standard footbridge/lifts combination) a new station should be in the region of £62,000 per platform metre (at 2025 prices).

Other outliers

Another station that could be classed (along with Soham) as a ‘political vanity project’ is Kenilworth.

Like Soham, it closed in 1965 when the local passenger service was withdrawn.

In 1976, when the National Exhibition Centre opened, Birmingham International station was built to serve the NEC and the adjacent airport.

From 1977, Birmingham-Banbury-London trains were re-routed from via Solihull (apart from a couple of commuter turns) to the new station on the Coventry line. Envious locals watched as trains zipped through every hour.

A long-running campaign to reopen a station (the original was demolished in the 1980s and the land was sold to a builders’ merchants) finally bore fruit when a grand new design was unveiled.

Planned to have two platforms - anticipating an extension of the Kenilworth loop - residents were expecting to gain an inter-city service.

Politicians did nothing to temper expectations, but the challenges of adding another stop (adding around ten minutes to the already over-tight CrossCountry Voyager schedules) was clearly too much. Instead, the existing Nuneaton-Coventry service was extended to Leamington Spa.

With a building designed to ape the original’s appearance, Kenilworth included a booking office and coffee shop.

Yet of the £11.3m cost, even less of the station was actually delivered. A ‘future-proof’ footbridge and lift-tower shell were built, but the second platform was quietly erased from the plans - yet the budget was untouched.

Even allowing for the compulsory purchase of the station site (at full market rates), and the grand specification, it becomes even more expensive when the second platform loss is factored in.

With Soham and Kenilworth, it appears that a common thread runs through both: who do you engage to deliver it?

Certainly, there’s no suggestion that the construction firms in either case received above-market rates for their work. But if you’re going to build a station, and have never done so, who do you call? The answer is an army of consultants, and the time-clock starts ticking.

While Network Rail is an ‘informed buyer’, in neither case did it lead the project. That was the respective councils, and (to date) both have refused to disclose where the money went.

It’s all the little ‘extras’ in a project that add up - those ‘ancillary costs’. And while consultants can be a good thing, if you don’t know the price of what you should be buying, it’s rather like handing over a blank chequebook.

Worse still, at Kenilworth, in the post-COVID industrial relations debacle, the Nuneaton-Leamington service was the first to be cut owing to train crew shortages.

In January 2021, less than three years after the station opened, all services were suspended by West Midlands Trains (WMT) because of staff shortages.

A reduced service resumed in April 2021, but in December 2021 WMT once again admitted its failure to run services on the Coventry-Leamington and Coventry-Nuneaton lines. Trains were eventually restored from March 2022.

This saw passenger growth stumble and WMT didn’t help either, being ‘lukewarm’ about Kenilworth’s prospects. The result is that the station is now permanently shuttered, with the booking office and coffee shop closed.

> Selected new stations, their facilities and costs (pdf)

Where next?

The answer as to why stations cost so much is not because ‘they just do’. It’s because ‘sometimes they can’.

To misquote Voltaire: “Excellence is the enemy of the good.”

But what we’re not getting with over-priced stations is good. Soham remains Exhibit A in the case for the prosecution.

Councils pushing ‘vanity’ projects seem to be good at over-spending on stations that end up having a poor service because they don’t integrate with the wider network.

For example, there are aspirations for a direct Soham-Cambridge service, but this is pie in the sky given that no such trains pass ‘the door’. This would also require extensive infrastructure elsewhere on the railway, even if there was a proven demand.

Kenilworth (population 22,538) and Soham (population 12,300) might aspire to such things, but aspiration’s first contact with reality is rarely a happy outcome.

Lessons to be learned are that you shouldn’t get a local authority to lead on building a station. They don’t have the expertise and are dependent on third parties who may not always provide best value for money.

A standard set of designs for small and medium stations from Network Rail could bring down costs, rather than starting from scratch every time. It works for McDonalds, which has triumphed in this field, taking a bare site, negotiating planning hurdles, and building its restaurants in double-quick time.

Clearly, Scotland has also shown (as it has on electrification) that having a rolling programme, learning from each project and applying those lessons to the next, is a model that’s well worth following.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.