Paul Clifton canvasses the opinion of rail leaders on SWR’s past, present and future to understand how the nationalisation of South Western Railway will affect services and the passenger experience.

In this article:

Paul Clifton canvasses the opinion of rail leaders on SWR’s past, present and future to understand how the nationalisation of South Western Railway will affect services and the passenger experience.

In this article:

- South Western Railway was renationalised on May 25, ending nearly 30 years of private control amid mixed expectations.

- Critics warn of continued service issues under public control, citing poor leadership, infrastructure problems, and outdated rolling stock.

- Labour promises reform through Great British Railways, but experts doubt significant change without long-term leadership and investment.

South Western Railway was renationalised in the early hours of Sunday May 25, ending more than 29 years under private control.

Owned since 2017 by First MTR, it is the first train operator to transfer from the private sector under the Labour government, which last November passed legislation to bring most passenger services back under public control.

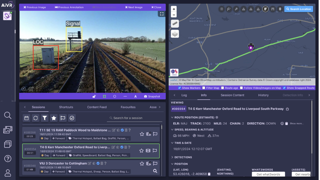

Transport Secretary Heidi Alexander highlighted the 0614 from London Waterloo to Shepperton as the first renationalised train, a Class 701 Arterio sporting stickers announcing: “Great British Railways - Coming Soon.”

SWR staff confirmed the first two services were halted due to overnight engineering work. The 0227 from Guildford was cancelled, and the 0536 from Woking was replaced by a bus. Cue BBC headlines about “the first nationalised train is a bus”.

SWR’s predecessor, Stagecoach’s South West Trains, had run the first privatised scheduled service on February 4 1996.

Alexander proclaimed “a new dawn for our railways”. She had visited SWR’s Bournemouth depot the previous Thursday, telling staff and a few selected journalists: “We are waving goodbye to 30 years of inefficiency and passenger frustration.

“We will sweep away decades of waste,” she promised, telling workers it was “a generational opportunity to fix our broken railways”.

She then thanked the workers for a “marvellous job” applying new logos to the train.

However, former leaders of what used to be Britain’s largest and most profitable passenger franchise warned that passengers would notice little change beyond a few fresh stickers on the sides of carriages.

They suggested there would be no improvements to services, with civil servants at the Department for Transport continuing to ‘micro-manage’ train operators - at least until Great British Railways takes control around 2027.

SWR is now part of the Department for Transport Train Operator (DFTO), headed by Chief Executive Robin Gisby, who has also become chairman of SWR.

Lawrence Bowman becomes managing director. Bowman was previously Network Rail’s Anglia route director. Before that he had roles at West Midlands Trains and East Midlands Trains.

All 5,600 staff have transferred to the public sector, retaining their existing pay and working conditions.

DFTO now has 18,500 staff and runs around a quarter of all passenger services. c2c is due to join on July 20, and Greater Anglia on October 12.

At the Bournemouth photo opportunity to unveil the new logo, Alexander stated: “Passengers will notice a fundamental cultural reset, with operators having to earn the right to wear the Great British Railways badge.”

Asked what that meant, Rail Minister Lord Peter Hendy told RAIL: “If we indulged in a massive rebranding process, then we would be putting a brand new name on something that wasn’t palpably different.

“We now have both punctuality and cancellation standards that are the same for the operations and infrastructure. They need to meet those standards on a consistent basis to prove to people that GBR is a better service.”

The government announcement stated that it “kicks off a total reset of the railways to improve performance and win back public trust”, although train operators already have to meet specific performance targets as part of their contracts.

“Yes, they have always had standards,” Hendy conceded.

“But some companies haven’t met them, notably due to a persistent shortage of drivers. But the primary thing discussed when standards aren’t met is whose contractual problem that is, and not the remedy for customers. This will be very different.”

It was not made clear what penalty there would be for failing to meet the standards, what the alternative to carrying a GBR logo would be following nationalisation, or why the “Coming Soon” logo was a necessary part of what the government called “a watershed moment”.

The SWR challenge

“There’s a bit to do with the South Western,” Lord Hendy told RAIL.

Himself a daily commuter on SWR’s suburban services, he said: “It is, frankly, not perfect at the moment. Punctuality is not bad. Cancellations are too high. They have a shortage of drivers. They have to get the new trains into service, because many have been sitting around for years.”

Ninety Class 701 Arterio trains were ordered in 2017, for delivery from 2019. But the first didn’t carry passengers until January 2024, and so far only up to seven ten-car trains are used each day, with most held in storage.

In April, in an attempt to get more of the fleet into service over the next two years, SWR announced that guards would close train doors at stations, despite Arterios being designed for driver-only operation.

Between 2017 and 2020, the RMT union had held 74 days of strike action over the role of guards on the new trains. Now the company conceded that drivers still faced “some specific challenges” in viewing along the train “under all light conditions” at a number of stations.

The intention is still to have drivers opening and closing the doors, but no date has been given. Most of the 750 main line drivers who will work the new rolling stock have yet to complete their two-week conversion course.

Hendy told RAIL: “If you’re a short-term franchise, you don’t necessarily think of the long-term health of the railway. Things are put off for the next people to deal with. Even on the South Western, franchise changeovers have not gone smoothly.”

He warned: “We will have to pay particular attention to cost, because it is too high. The bottom line is the net cost to the taxpayer and the best possible service to passengers. For the first time in 30 years, somebody will be in charge of both the operations and infrastructure, and be held accountable for the whole way the South Western will be run. That’s a really important moment.”

A senior industry source set out the scale of that challenge, telling RAIL: “Managing directors are fed up with micro-management. They are completely neutralised by civil servants, and have no freedom to decide anything. The leadership need some headroom, as at Southeastern and LNER, which are doing well.

“There are poor relations with the unions. There’s a lot of mistrust between the operator and the DfT, and between the DfT and the Treasury.

“They will have to sort the Arterios, some of which require repairs due to degradation before they’ve carried a passenger. Sort the union relationship. Run longer trains.

“Then have the first timetable recast since Andrew Haines did it more than 20 years ago, when he ran SWT, because the pattern of passenger demand is different now. There needs to be less Sunday engineering work, moving it to be less disruptive.

“And the diesel Class 159s will have to be replaced with battery trains and discontinuous overhead wires to Exeter.”

First Group reflects

First Group has celebrated “hundreds of millions of pounds” of improvements over the eight years it has held the SWR business.

They include a new depot at Feltham and a £70 million refurbishment of the Desiro fleet. It said that the rollout of the Arterio fleet had been “slower than expected” due to factors beyond its control.

First Rail Managing Director Steve Montgomery said: “Passengers have been at the forefront of service improvements throughout our stewardship of these important routes. Right up until the final weeks we have continued to innovate, with a new fast WiFi service being rolled out.

“Above all, I would like to say thanks to our SWR colleagues for their hard work and dedication to our customers.”

Passenger perspective

“Many care less about who runs the trains, and more about seeing real, tangible improvements,” says Jeremy Varns, campaign co-ordinator of passenger group SWR Watch.

“The government is sure to take credit for every new Arterio rolled out. Yet these were scheduled to enter service in 2019 and most problems are not attributable to the previous operator.

“Other fundamentals need urgent attention. Fares must become more affordable, and timetables need reviewing. At the very least, service levels should match those achieved before the pandemic.

“Delays caused by signal and track failures are a persistent frustration. Real investment in infrastructure is essential.

“Without meaningful reform and financial backing to deliver a railway passengers can rely on, Labour risks losing support for its renationalisation agenda.”

SWR perspective

What did Waterloo’s privatised railway achieve?

“This single franchise encapsulates all the highs and lows of the entire privatisation era,” says Sir Michael Holden, who in 1994 was operations manager of what was then the South West division of Network SouthEast.

“It started with the buccaneering bus bandits. They thought British Rail was inherently inefficient, and that they could strip out costs wholesale.

“They got a nasty shock with the train drivers. I had a train crew strategy, but I was told I didn’t know what I was talking about. They paid off hundreds, then realised they were needed after all.”

“Privatisation happened at the right time,” counters Graham Eccles, who joined South West Trains not long after privatisation, as managing director and later chairman.

“Railways grew because the economy was good. GDP was going up. Central London employment was going up. That timing was entirely by accident - John Major simply wanted to get rid of the railway.

“Everybody was happy,” he tells RAIL. “Stagecoach was making shed loads of money. The government was creaming money from the franchises - every time they went to market, they came back with better value for the Treasury.

“We had a very reliable service. The staff loved it - they were getting decent pay rises. Because the companies were profitable, they were investing in their staff, in training, in making their jobs more fulfilling.

“Yes, we had two or three years at South West Trains of sorting out the trade unions. But once we reached equilibrium, we never lost another day to disputes at Stagecoach. That was very important.

“With Stagecoach, you know exactly where you stood. They were in it to make money. But they did that by delivering a quality product. When I left, South West Trains was making £1m clear profit a week. It was a fantastically successful business.”

Others would point to money being taken out of the railway by shareholders.

Holden agrees this was a golden era of privatisation, driving performance and growth: “Mk 1 stock had to be replaced. And that revealed just how little understood the whole traction and power supply issue was at the time. I would argue not much has changed in the intervening 25 years, because we’ve still got power problems on the East Coast Main Line today.

“I was running Railtrack Southern by then. All three train operators had ordered replacement train fleets, but the power supply was incapable of running them. Nobody had factored that into the planning or funded the work, so it all had to be done in a hurry by the Strategic Rail Authority.”

SWT was by far the biggest rail franchise, with annual revenue above £1bn, operating without subsidy and paying a large premium to government. But in recent years, the reputation of services from Waterloo has declined significantly. What went wrong?

“The Treasury screwed the price harder, so people were making less money,” says Eccles.

“That reduced the ability to invest in the business. And the one thing we all learned with COVID in 2020 was that a privatised railway, with no assets or balance sheet behind it, would go bust in 24 hours when the country locked down. That was the nail in the private sector’s coffin.

“The lesson to draw: privatisation is great when the economy is great. When the economy is not great, it is in real trouble.”

Holden agrees: “The franchising system became too complicated for its own good.

“In 2017, the franchise went to First and MTR. The incumbent, Stagecoach, knew too much about power supply, timetable capacity and pension risk, and refused to accept the terms. The challenger knew too little, and won with an undeliverable bid.

“The wholesale fleet replacement relied on revised methods of work. British Rail had tried to introduce Driver Only Operation on the South Western suburban lines in the 1980s and failed, because the drivers’ union ASLEF was against it and found lots of safety objections.

“That is exactly what is happening again today with the Arterios. History is repeating itself. Lessons have not been learned.”

Can renationalisation make things better for passengers?

“It can. But it requires a change of attitude,” warns Eccles.

“It’s been all about reducing subsidy. The future has to be about reducing net subsidy, which is not the same thing at all. It’s about growing the business. To do that, you need to look back to the days of the privatised railway, when it was reliable, it was comfortable, on time, and trains ran on Saturdays and Sundays.”

“The pandemic brought close government control over the decision-making, and not for the better,” says Holden.

“We’ve seen aversion to risk and over-zealous focus on cost control without regard for revenue, and a short-term focus that has led to some strange decisions on train leasing costs.”

It was reported in April that renationalisation of SWR would cost £50m more in each of the next five years in increased train leasing costs, because the DfT would only commit to five-year leases from Angel Trains, Porterbrook and Rock Rail. Labour’s General Election manifesto had promised that nationalisation could be achieved “without costing taxpayers a penny”.

“All of those things have been bad for the whole passenger experience, and for growth,” says Holden.

“The long-delayed transition to Great British Railways has been overtaken by nationalisation of the franchises. In my opinion, it is most unlikely that anything material is going to improve for the foreseeable future. It might even get worse.”

Eccles agrees: “I don’t think there will be much change for now. There is no executive leadership in the railway industry. Yes, there is Sir Andrew Haines at Network Rail, but the Department for Transport are neither business-oriented nor people-oriented in terms of customers. They will run the railway to reduce the subsidy.

“I don’t think anything will change until they appoint a chief executive and chairman of GBR - people who will be there for the next five years in each job, who will take the railway by the scruff of the neck and drive it forward. Without that happening, I cannot see the catalyst for improving the performance of the railway.”

Holden expands: “We have some experience of franchises that have been put into the public sector. LNER has prospered. But Northern and TransPennine Express have had a torrid time. And for the time being, we are going to swap one set of government micro-managers for another set of micro-managers, often with the same people calling the shots.

“Renationalising won’t make it better until you do things differently. SWR was effectively already nationalised.”

For a full version of this article with more images and data, Subscribe today and never miss an issue of RAIL. With a Print + Digital subscription, you’ll get each issue delivered to your door for FREE (UK only). Plus, enjoy an exclusive monthly e-newsletter from the Editor, rewards, discounts and prizes, AND full access to the latest and previous issues via the app.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.