In our latest extract from Bradley’s Railway Guide: A Journey Through Two Centuries of British Railway History 1825-2025, we look at how salvaging the railway‘s unwanted metal was essential to Britain’s war effort. And how the practice has evolved into today's recycling.

The past: 1941

In our latest extract from Bradley’s Railway Guide: A Journey Through Two Centuries of British Railway History 1825-2025, we look at how salvaging the railway‘s unwanted metal was essential to Britain’s war effort. And how the practice has evolved into today's recycling.

The past: 1941

The advertisement sections of the wartime railway press were dominated by full-page notices placed by ‘British Railways’.

The name may seem anachronistic, coming several years before the main companies were nationalised under the same title by the post-war Labour government.

In fact, the Big Four had adopted this umbrella term in the 1930s, using it especially in promotional contexts such as exhibition trade stands. In wartime, the label acquired additional force as the companies came under effective state control.

Salvage - most of which would now be termed recycling - was central to the war effort from the outset.

Britain’s railways, heavily dependent on ferrous and non-ferrous metals for so many aspects of their work, were an obvious source. Linesides throughout the country were scoured for reusable metal, especially old rails and their cast-iron supports.

On the London, Midland & Scottish Railway the campaign to recover materials was initiated in April 1940 by the company’s president Lord Stamp, who lost his life in a direct hit on his home the following year. In the capital, the LMS provided specially adapted vans, attached to ordinary trains, to collect salvaged materials from its stations and depots.

In 1941, British Railways placed an advert in the press commending an unnamed railway foreman who had collected 500 tons of salvage in just eight weeks.

Newspaper reports allow him to be identified as D. Wright of the LMS’s Vauxhall district in Birmingham. According to the Birmingham Daily Gazette (June 27 1940), Wright’s 500 tons of salvage included “old tin cans, metal stoppers from bottles, tobacco tins, and any old paraphernalia he could lay hands on”.

To inspire further efforts, the company offered three prizes of dartboards to those of its railway messrooms who could gather the most scrap metal in a month, to be judged in proportion to the number of men on the books at each.

In August 1944 it was announced that the railways had collectively recovered a million tons of salvage, comprising metal, paper, textiles, rope, twine and rubber.

Some 1,621,704 bottles were also salvaged, as well as 3,880,000 razor blades, for which public collecting points were provided at railway stations.

The proceeds from selling the donated blades, which fetched around five shillings per thousand, went to armed forces benevolent funds.

Larger items retrieved for the furnaces included the railways’ share of the many ornamental railings that were stripped from the frontages of buildings up and down the country, and a few historic locomotives that had been set aside for preservation, such as No. 4 Ryde, a little Isle of Wight Railway 2-4-0T of 1864 - to the enduring regret of enthusiasts.

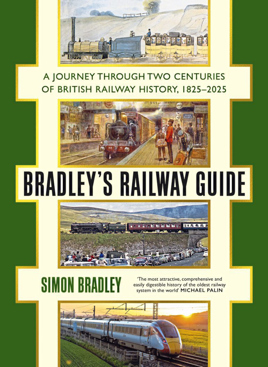

Reproduced with permission from Bradley’s Railway Guide: A journey through two centuries of British railway history, 1825-2025 by Simon Bradley (Profile Books, £30).

The Present

Richard Foster looks at how metals continue to be recycled, but questions whether the cycle itself needs to be updatedThe railway has always been good at reusing obsolete materials, with that ability being emphasised by the extreme conditions of war in 1941.

The need for metal to make armaments generated unprecedented demand for reusing scrap material. Enthusiasts might bemoan the loss of Isle of Wight Railway 2-4-0T Ryde, preserved by the Southern Railway, but we must be thankful that many similar priceless relics didn’t go the same way.

Recycling, quite rightly, has taken on greater prominence in the 21st century.

But what counts as recycling? Is it as simple as picking up pieces of scrap metal from the lineside to go into a skip? Or it could be offering a redundant signal box to a preservation society so that it can be reused?

Collecting redundant items doesn’t mean that they have to go into a skip. The London Transport Museum has recognised that people like collecting surplus equipment (relics, if you will), and has made selling bits of withdrawn trains or turning them into furniture or accessories a lucrative sideline.

BR, of course, used to have Collector’s Corner - an emporium chock full of relics that it thought people might want to buy. While the quality of its offerings tailed off towards the end of its life, there is clearly a market for a 21st century equivalent, if the prices for items such as signal arms on eBay are anything to go by.

But recycling covers much more than this. The Great Western Railway had recycling down to a fine art. In the wake of the 1923 Grouping, it carefully assessed which locomotives of the hundreds that it inherited were capable of further use, and then made a plan to overhaul and reuse them. This kept seemingly obsolete locomotives going for decades after their contemporaries.

Today’s operators have inherited this spirit. GB Railfreight’s Class 69s and ‘73/9s’ are perfect examples of machines whose futures were uncertain, but which after a thorough rebuild will continue to serve the railway for years to come.

They’re not the only examples, of course. One could also point to Vivarail’s D-Train or Class 57 as well.

Carl Waring, from consultancy Frazer-Nash, explained the theory of the circular economy to delegates at 2024’s UK Light Rail Conference.

He said that our current economy is geared towards taking raw materials from the earth, manufacturing something like a new train, and then throwing it away at the end of its life. To replace that train, the cycle continues, stripping more raw materials from the earth.

The circular economy, Waring explained, looks to continually renew products by promoting manufacturers not to make products that eventually become obsolete, while promoting interchangeability, standardisation and interoperability.

If you make something last longer by continuing to manufacture parts so that they’re always available, Waring proposes, you halve its carbon footprint.

But how often, he asks, is this considered? Does a train manufacturer, for example, design its vehicles so that they can be upgraded over and over again?

Alstom spent £117 million transforming the Class 390 ‘Pendolino’ fleet (completed in 2024). But how much might have been saved had that refurbishment programme been ‘designed in’ when they were originally built nearly 25 years ago?

Maybe it’s time for the railway to consider taking recycling to the next level…

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.