With this year’s ‘Railway 200’ celebrations now upon us, Dr Joseph Brennan looks at the remnants from the original 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway that we can still see today.

The Stockton & Darlington Railway, as described in London Mechanic’s Magazine in the October 17 1829 edition, is a railway “on which steam-power was for the first time employed to propel passengers as well as goods, and with a degree of success which began to open the eyes of the public to advantages of which they had not even dreamt”.

It’s a statement demonstrating that even before the close of the decade during which it opened, the S&DR was already being celebrated as the start of the railways as we now know it.

Little wonder, therefore, that so much excitement (and preparation) has accompanied the lead-up to the S&DR’s bicentenary in 2025 (the line having opened on September 27 1825).

Over the coming months, RAIL will carry various heritage stories. It makes sense that the first - less than a year out from the milestone celebrated as 200 years of the railways - takes stock of the surviving S&DR structures connected with that 1825 opening. Some are still in active use on the modern network.

It ‘makes sense’ because the celebration, restoration and preservation of these survivors is a project that has been in the works for a number of years.

And perhaps the best example surrounds the structure most famous along the original line: Skerne bridge - mighty masonry that is synonymous with the S&DR’s opening day.

Skerne bridge

In 2021, Historic England (HE) gave the bridge the top Grade 1 designation. It joined an exclusive club of just seven Grade 1 Listed railway bridges in England.

Skerne Bridge had been designated as a Scheduled Monument in 1970, although given it remains in regular railway use, protection as a listed structure was deemed more appropriate.

In fact, it is believed to be the oldest railway bridge in the world that is still in its original use.

Designed and completed in less than eight months by Ignatius Bonomi, it is the architect’s most famous work and has come, over its history, to embody the momentous achievement of the S&DR.

Though recognised as a Grade 1 gem during this present decade, Skerne has been in the British consciousness for some time. It appeared on the £5 note (Series E, in circulation 1993-2003), as well as in many artistic works commemorating the railway’s opening.

Interestingly, most artists depicting the bridge show it with elegantly curving wing walls - for example, John Dobbin’s famous 1870s commemorative painting Opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway.

However, these were an 1829 strengthening addition made under the direction of John Carter, who had been appointed Inspector of Masonry for the railway in 1824.

As it was first conceived, the line expected to transport around 10,000 tons of coal per year. But by mid-1828 it was carrying more than five times this amount, most of it passing over this bridge - a testament to the line’s success.

These wing walls strengthened the embankments that were showing signs of potential failure at the time, and the main line was upgraded to double track in the early 1830s.

Later in the 1800s (probably around the time of the S&DR’s merger with North Eastern Railway in 1863), a new bridge was added to the northern side of the original bridge, bringing an additional three lines, and Carter’s wing walls were covered with new walls made of rock-faced stone. It is believed that Carter’s originals remain buried under the enlarged embankment.

The added bridge was removed in the second half of the 20th century, its piers remaining today.

Skerne stands as a powerful symbol - its story of sensitive strengthening and expansion while staying true to an original ethos evokes the spirit that the S&DR inspired across Britain.

Our survey here is a selective one, spanning some of the highlights and guided by recent listings and ongoing initiatives to get these remarkable survivors ready to celebrate their big two-zero-zero this year.

Legacy of the S&DR

A bigger-picture example of the preparation for the S&DR’s bicentenary was its selection in 2017 as one of HE’s Heritage Action Zones (HAZs) - beginning in 2018 and running for five years.

HAZs entail HE working with partners to bring new life to England’s great heritage sites, unlocking their potential.

The Friends of the Stockton & Darlington Railway, formed in 2013, provided the impetus for S&DR’s selection as a HAZ, and since 2017 there has been increased protection and restoration of some of S&DR’s greatest assets.

But why exactly is the S&DR so significant?

As David Knight explains in a 2021 HE report, it was not its use of a new technology or mode of traction.

The S&DR was not the first railway to be constructed following an Act of Parliament. That was the Middleton Railway in Leeds in 1758.

Nor was it the first to use malleable (wrought) iron rails. Coalbrookdale had been using these for horse-drawn railways since at least the 1760s, with these carrying steam locomotives by 1802.

It was not the first public railway authorised (there was one in Surrey in 1803), nor the first authorised to carry passengers (there was one in Swansea in 1807).

It was also not the first to use a steam locomotive to pull passengers (Euston Square had done this in 1808, admittedly for entertainment purposes only), with the Middleton Railway becoming the first sustained commercial steam railway by 1812.

Instead, Knight writes: “The importance of the S&DR lies in the fact that in 1825 it brought all of these developments together, offering the world’s first steam-locomotive public railway service.”

George Stephenson was S&DR’s Chief Engineer and became known as ‘the Father of the Railways’.

Much credit is also owed to Timothy Hackworth, the S&DR’s Superintendent of Locomotives, the railway’s resident engineer, and who (like Stephenson) was active in promoting information about the railway to an international community of engineers and railway promoters, helping to ensure its influence. Therer are lessons here even today.

Hackworth also made improvements and alterations to locomotives and to the ‘inclines’ of the line, which is our setting-off point.

On the coal trail

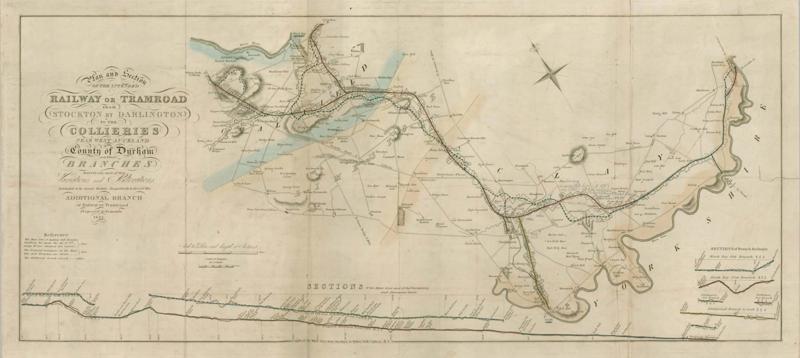

Witton Park Colliery in Durham was the western terminus of the 1825 S&DR line (for our purposes, and as delineated by HE, a line running Witton Park to Stockton-on-Tees).

Although famous for the line’s use of steam locomotives, originally these were only used from Shildon eastwards, before the opening of the Shildon tunnel in 1842 changed this.

To the west of Shildon the line included two inclined planes, used to traverse the Etherley and Brusselton ridges and linked by a short, level section that used horse traction to cross the Gaunless river valley. The S&DR utilised and expanded technologies of various colliery railways and wagonways around Tyneside, in this regard.

In 2023, a number of S&DR sites and structures received expanded protection, with some being listed for the first time.

The inclines at Etherley and Brusselton were among those to benefit, designated as scheduled monuments - but also to appear as new entries on HE’s Heritage at Risk Register 2023. The designation protects standing, earthwork and buried remains at the sites.

Etherley Incline was reached first from Witton Park, with some heritage survivors at the site including well-preserved, substantial earthworks and boundary walls that give insight into how the incline was arranged.

Of the two inclines, Etherley has more original remains to explore, much of which had previously been scheduled (in 1976, along with a length of the incline at Brusselton).

After being hauled by horse-drawn wagon, coal made its way up the incline by a stationary steam engine.

A highlight at Etherley that has also had protection for some time is the 1825 engine pond - it’s included in the scheduling of the incline, but was also listed in its own right in 1987, at Grade 2.

This circular pond is around eight metres (26ft) across and constructed with rubble and sandstone walls. It still holds water today, being fed by a stream from the west. It provided water for the stationary steam engine that powered the incline.

‘Etherley Engine’ comprised an engine house to the south-east of the pond (it has been lost), as well as an engineman’s house that reportedly survived into the 1980s before being demolished.

There was a second circular pond at the site, of which a depression remains, while the remains of the boundary wall are also visible.

The engine pond at Etherley is a rare surviving stone structure on the northern section of the S&DR. Further stone remains can be found in the abutments for where horse-drawn coal wagons crossed the River Gaunless in West Auckland. These abutments were for a bridge of great significance, and an arena where Stephenson can take the title of a real pioneer.

Gaunless Bridge

Gaunless Bridge was completed in 1823 as purportedly the world’s first iron railway bridge (the 1793 Pont y Cafnau tramway bridge in Wales is cited by some as the first).

A fourth span was added in 1824, and on opening it carried horse-drawn coal wagons.

The bridge continued in use until 1901, when it could no longer take the loads of increasingly heavy coal wagons.

The iron bridge itself was dismantled with care in 1901 and preserved - a recognition of its significance. It was later rebuilt and played a role in an exhibition celebrating S&DR’s 100-year milestone. It then moved to York, nad was displayed in the North Eastern Railway’s museum and then the National Railway Museum.

At the NRM, it was located in the car park with no display board to indicate its importance. This was redressed in 2020, when it was announced that the bridge would go on permanent display at Locomotion in Shildon. It is now open to the public as a “star object” of the museum after undergoing restoration.

During the conservation process, the original colours of the bridge came to light, and it was repainted early in 2024 in a striking green and white.

It is right that this iron bridge should be preserved, for here Stephenson took a truly innovative approach.

Near this site, conventional stone-arched bridges can be found crossing two small becks (the Oakley Cross and then the Hummer Beck).

These structures are well-preserved, 1825-aligned survivors, and all are included in a 2023 Scheduled Monument taking in the remains of the 1825 line running along the River Gaunless.

The scheduling also includes a sample section of the 1856 Tunnel branch. This branch was more heavily engineered than the 1825 line, showing the rapid development of the railways after the opening of the S&DR into what we would recognise today.

These are all great survivors, but for me it is Gaunless bridge that is the most special.

Stephenson was in new railway terrain with this structure. It was the germ of an idea that would inspire his son Robert and a close rival (and friend) of his son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, for other iron icons in the Grade 1 club - namely, Robert’s 1849 Tubular bridge in Conwy (listed by Cadw) and Brunel’s 1859 Royal Albert Bridge.

Interestingly, Stephenson had planned to use a wrought and cast-iron arch to span the river Skerne, but it was the S&DR’s board that stopped him - not confident that this technologically cutting-edge approach would be successful.

As impressive as Skerne bridge is, I can’t help but wonder what might have been had Stephenson been permitted to take that leap, and how it might have reshaped the S&DR in the popular imagination.

Just think of the great failed experiment in cast-iron of Thomas Bouch’s first Tay bridge, an 1879 catastrophe that led to another top-tier icon - the steel splendour (and strength) of the 1890 Forth Bridge (a Category-A structure).

Even Stephenson’s son, Robert, came close to reputational ruin when the weaknesses of cast-iron were shown in the collapse of his Dee bridge in 1847.

As for those Gaunless bridge abutments … these are within the scheduling and remain in situ, although they have suffered somewhat at the altar of anti-social behaviour. In fact, they have been named on HE’s Heritage at Risk Register owing to their deteriorating condition.

But their future looks bright, following the announcement last year that HE has awarded Durham County Council £161,000 to repair and revitalise the remains, and to install a new bridge deck that will form part of the new 26-mile Stockton and Darlington Railway Walking and Cycling route.

Brusselton Incline

At the second incline, stone sleepers used on the S&DR are a highlight, with the Brusselton Incline Group having exposed the stone blocks in 2014 by clearing surrounding vegetation.

But it’s the ‘Old Engine Houses’ 1-4 at Brusselton Engine that are most important.

These examples of local vernacular construction constitute the best-surviving group of S&DR buildings dating to the 1820s (remembering that the 1820s and 1830s was the period when the railway was most influential, with Brusselton receiving visitors from around the world.)

Listed at Grade 2, Number 1 was workers’ accommodation, 2 was the engine house, and 3 and 4 were accommodation for the engine man and fireman/blacksmith operating the engine.

The workers’ accommodation is significant as perhaps the earliest surviving purpose-built railway workers’ housing in the world.

But visitors will likely enjoy the engine house most, as it retains direct evidence of its original use as the engine house that powered the Brusselton inclines, (1825-31), as engineered by Stephenson and modified by Hackworth.

You can see this evidence of original use in the outline of a tall arched opening in the north wall of the building. The engine was originally fed from two circular ponds, although these were subsequently replaced by a large, square reservoir.

On the modern passenger trail

Originally, the railway entered Shildon from the west via the Brusselton Incline, with Shildon being the start of the original 1825 steam-hauled railway.

After a journey by horse- and steam-powered incline, it was here that passenger and goods wagons were hitched to No. 1, 0-4-0 Locomotion, for a journey by steam to Stockton.

‘New Shildon’ became a railway mecca, starting with the opening of Shildon Works in 1825 (later becoming the Wagon Works). The Shildon Wagon Works operated from 1825 to 1984, but development over the years removed any trace of the railway as it existed prior to 1831.

Even Locomotion, now on proud display in the Shildon museum of the same name, was extensively rebuilt over the years.

In fact, a report commissioned by the National Railway Museum and released on the 2023 anniversary of the Stockton & Darlington Railway Act finds that the steam engine on display today does not contain identifiable parts dating to 1825, although the boiler barrel dates from 1827 and was originally from sister locomotive Diligence.

What we see today dates from 1856-57, being the fourth incarnation that is reminiscent of its 1825 appearance, as the report’s researchers Dr Michael Bailey and Peter Davidson reveal.

Even the famous name itself is a work of reinvention. The locomotive was originally called Active and only received its number in 1827 and that famous name in the summer of 1833, when it likely received its cast nameplates (the ones we see today are later additions).

There are, however, original 1825 structures that remarkably are still in use on the modern network.

Skerne bridge may be the pièce de resistance, as its 2021 Grade 1 listing attests. But there are other gems with original elements carrying trains today, some of which have benefited from more recent recognition and protection as part of gathering momentum for a year of celebrations.

Culvert and Accommodation Bridge

Although little survives east of Shildon that is original to 1825 (construction of the Shildon Sidings removed 1825 traces), as we near Darlington we find two original features on the live line in the parish of Coatham Mundeville.

Stephenson’s trademark approach to railway engineering would be hugely influential to the spread of the railways and the formation of a viable network, well-engineered and including stretches still serving us today.

His approach was to engineer rail routes as straight and as level as possible, despite the added expense of embankments and cuttings (with their attendant bridges and culverts) that was necessary to achieve this.

Stephenson’s straight-and-level route realigned an original, rather circuitous, version planned by George Overton and authorised by an 1821 Act of Parliament.

This necessitated a second Act of Parliament that was passed in 1823, authorising Stephenson’s straighter route - a route that included the crossing of Dene Beck and Myers Flat.

It’s at Dene Beck where we find our first original feature of significance - a culvert in the embankment carrying the beck under the railway, located 260 metres north-north-west of where the railway crosses the A1.

Despite being more modest structures, culverts are rich sources for early railway lines, with many on extant sections of the S&DR likely to be original features.

This stream culvert is of coursed and ashlar sandstone, and a good example of Georgian masonry construction that is characteristic of the early railway.

Think of it as a bridge in miniature. In fact, that is how it is described by the listing authority, as “similar in design to the slightly more elaborate accommodation bridge about 60 metres to the south and the larger bridge over the Hummer Beck south of West Auckland, both of which are also thought to be original structures of 1825 line”. Such proximity creates ‘group value’ between these two structures.

The bridge south is a railway underbridge that spans a farm track.

The 1821 and 1823 Acts of Parliament granted the S&DR powers to compulsorily purchase the land required to build its railway, but also placed several obligations on the company. One of these was to provide bridges not only for public roads, but also for landowners whose land was divided by cuttings or embankments.

Known as accommodation or occupation bridges, these structures were an underestimated company expense that placed considerable strain on finances before the railway opened in 1825.

This now-listed example provides access through the railway embankment, likely for Stanley Farm.

The fine detailing of S&DR bridges probably didn’t help the ‘bottom line’, as this one was of smoothly dressed ashlar stonework, the semi-circular arch of voussoirs with a roll-moulded stringcourse arch ring.

It matched other bridges along the line and created a consistent ‘railway style’ - something that was highly influential. (For those interested, the aesthetic demands of landowners on the railways that cut through their lands led to some very fine bridges and tunnels, especially in the case of stately homes - as explored in RAIL 956.)

The culvert and accommodation bridge near Dene Beck on the live line between Shildon and Darlington were listed in their own rights at Grade 2 last year.

Whether or not a building or other built structure is listed is determined by a set of benchmark principles and by a process of inspection and consultation, including in the case of the live line with the owner Network Rail.

Having original elements, even to a line as foundational as S&DR’s 1825 version is not necessarily a guarantee of listing.

Myers Flat

A second accommodation bridge on the live line between Shildon and Darlington, located at Myers Flat, has also undergone recent listing consideration.

As part of the consultation, Network Rail responded that the Myers Flat bridge is timetabled for major refurbishment in 2026-27, and that the current deck is a replacement (dating to 1943).

Compared with the bridge and culvert that were listed, the bridge at Myers Flat is the most altered.

The advice report does acknowledge historical interest with the bridge, including that its 1833 widening contributes to its interest as “a marker of the early success of the railway”.

Yet the loss of its original masonry arch counted against it. Had there been a 19th century wrought-iron trough girder replacement, rather than the rather common and ‘utilitarian’ 20th century reinforced-concrete deck we see today, it may have made the benchmark for a Grade 2 listing - given its reuse of original curved masonry abutments built for the 1825 opening.

Alas, it did not, and the surviving masonry abutments were deemed not to compensate for the loss of its original arch. It will be interesting to see whether the abutments survive NR’s timetabled refurbishment of the bridge.

Perhaps, the process of its consideration for listing will engender a spirit of conservation when it is refurbished. As the report on it notes, it “does retain some early fabric” of “George Stephenson’s pioneering engineering to cross Myers Flat”.

Its location adjacent to the ruins of Coatham Grange/Myers Flat farm make it an attractive place to visit. Those interested should plan that visit soon.

Gathering steam for 200

The recent suite of listing and restoration efforts of structures original to the 1825 S&DR line is of vital importance and should continue.

But we need to remember that despite living in an era where a preservation-minded ethos for our industrial heritage is gaining momentum, more can always be done.

For example, not far from the culvert and accommodation bridge now protected at Grade 2, near Heighington station, we have the Hitachi Newton Aycliffe train building facility that opened in 2015.

The remains (stonework abutments, likely) of an accommodation overbridge original to the 1825 railway were demolished in around 2014 as part of the Hitachi track improvements. It had crossed the railway south of Moordale Park.

In his 2021 report for HE, David Knight describes this loss as illustrative of “the potential issues with preserving original features on the working parts of the railway line”.

It is worth noting that Hitachi is listed on the same report as a member of the S&DR Heritage Board - a board that secured the railway’s candidacy for HE’s 2017 round of HAZs.

In the vicinity of the lost remains of an accommodation overbridge, immediately inside the boundary fence on the west side of the live railway line, is an S&DR boundary stone. First listed at Grade 2 in 2022, it is believed to have been placed before the opening of the line in 1825.

As we approach the bicentenary, it is yet another example of how efforts are being made to safeguard S&DR heritage for centuries to come, even those relics located within the boundaries of our modern, live network.

This tour has been a selective one. There are many more traces of the original S&DR with us today, as well as important structures that came in its near wake.

But our final stop comes, rightly, at the end of the 1825 line… yet not as you might think.

The route ended at a series of wharfs along the river close to the town. What we would associate with a railway terminus came later.

Inns built by the S&DR along the line would serve as its earliest proto-railway stations, such as one in Darlington that was listed at Grade 2 in 2023. Located on High Northgate, it trades as The Railway Tavern and is a little later than most of our stops (built 1826-27). The S&DR inn at Stockton is on Bridge Road, dates from 1826 and is listed at 2*.

In the pure ‘in-service-for-the-1825-opening’ sense, it’s the walling remains of a coal depot built for the railway’s opening that form our Stockton great survivor.

This walling was listed at Grade 2 in 2023. Further out, earthworks and associated features of the 1825 line within Preston Park in Preston-on-Tees were also designated as a Scheduled Monument in 2023.

The coal depot walling extends south-west from the Grade 2* Listed former S&DR weigh house (also the first permanent building constructed by the railway for its Stockton terminus).

Modelled on the typical toll houses built for turnpike roads (including domestic accommodation), the weigh house has enjoyed protection for some time (being first listed in the 1950s).

The weigh house was key to the company’s income generation through its goods traffic - far more significant than passenger services in the early years. It was here that S&DR’s first rail was ceremoniously laid on May 23 1822 - testament to the site’s importance to the company.

Interestingly, this building was famously mis-identified during centenary celebrations, when in 1925 a plaque unveiled by the Duke of York erroneously claimed: “Here in 1825 the Stockton and Darlington Railway company booked the first passenger thus marking an epoch in the history of mankind.”

In fact, the weigh house was not completed until six months after the first passengers had travelled on the railway. And it is not thought to have been used as a booking office in the 1820s, although it may have been employed as one for a time after 1833.

The plaque was lost, then reinstalled at the site by its operator the Bridge House Mission in 2018, according to a BBC report.

For this story, we have followed the original 1825 line from Witton Park to Stockton-on-Tees, marvelling at just some of the remaining structures and with a focus on recent preservation efforts. This includes heritage along stretches of live line.

That some of these traces from 1825 still serve us in a practical capacity after 200 years is nothing short of remarkable.

In the words of Knight: “Such was the legacy of the S&DR and George Stephenson’s engineering, that much of the original line and infrastructure remains in use today. It set a precedent that would change the world.”

A year-long celebration as part of Railway 200 (railway200.co.uk) has now formally begun.

In March, ‘S&DR200’ gets under way, running for nine months (sdr200.co.uk).

Three local authorities with the S&DR within their boundaries (Darlington Borough Council, Durham County Council, and Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council) are also running initiatives, and there will be many more besides these.

Keep an eye on RAIL over the coming months for an update on heritage preservation efforts and a look at some of the initiatives being run, as well as news of the celebrations themselves.

About the author: Contributing writer Dr Joseph Brennan is an award-nominated author of historical fiction with a penchant for Victorian-era rail.

For a full version of this article with more images, Subscribe today and never miss an issue of RAIL. With a Print + Digital subscription, you’ll get each issue delivered to your door for FREE (UK only). Plus, enjoy an exclusive monthly e-newsletter from the Editor, rewards, discounts and prizes, AND full access to the latest and previous issues via the app.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.