Network Rail’s recovery programme to stabilise performance between Reading and London Paddington has been running for a year. It has another year to go. Paul Clifton joins the project leaders to assess progress.

In this article:

Network Rail’s recovery programme to stabilise performance between Reading and London Paddington has been running for a year. It has another year to go. Paul Clifton joins the project leaders to assess progress.

In this article:

- Project Brunel tackled chronic failures on the Reading–Paddington line, improving performance after years of infrastructure neglect.

- Key fixes included vegetation control, drainage repairs, and pigeon-proofing, reducing delays by 21% in one year.

- Long-term success hinges on sustaining changes, better cross-industry collaboration, and restoring passenger trust.

Reading to Paddington services were making national headlines for all the wrong reasons.

In 2023, it was the only route in the country where performance was getting steadily worse. Failures were occurring almost every day. Network Rail admitted it was letting passengers down.

In early 2024, it announced a remedial plan, grandly titled Project Brunel. Money and resources were thrown at the problem.

The first phase was to stabilise falling performance. The second phase was to turn that around and to get more trains running on time, with fewer infrastructure failures.

One year on, in spring 2025, those phases are largely complete. Now the task is to turn that short-term effort into sustained improvement, ensuring that recent gains do not slip back and that “business as usual” is left at a consistently higher level when the project team is disbanded.

RAIL was invited to join that project team, with no questions off-limits.

What had gone so wrong?

When an overhead power line failed in west London on December 7 2023, seven trains were stranded for up to four hours. Some 4,000 passengers climbed down from their trains onto the tracks to walk to the nearest station.

It was the most serious incident in an increasing pattern of passenger woes. In the previous month there had been four broken rails. A request made under the Freedom of Information Act revealed that infrastructure faults between Reading and Paddington disrupted passengers on 361 of the 365 days to November 30 2022.

At the time, RAIL quoted a senior industry source: “These incidents are part of a wider picture of decline on a route supposed to have seen substantial investment for electrification and the Elizabeth line. But actually, it is left with many assets in poor condition.”

The Office of Rail and Road launched an investigation. Soon afterwards, the regional director for Network Rail resigned and left the organisation.

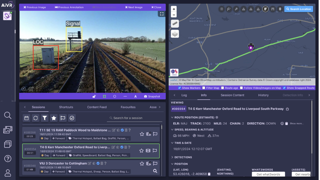

Under new management, the recovery programme was drawn up. The people leading it even have Project Brunel stickers on their laptops, as RAIL found when invited to join them at Reading.

They uncovered no single reason why performance had continued to fall, relative to the rest of the country.

However, since the launch of Elizabeth line services in 2022, the corridor has become the busiest stretch of overhead line power in the UK.

Track use has increased by 17%. And, critically, the total weight of trains on the track has increased by more than one-third. Equipment has been working harder and wearing out faster.

The railway has been transformed - the enormous success of the Elizabeth line means this is now a metro-style, high-frequency route. That’s in addition to the long-distance Great Western services that have fully recovered from COVID. Plus the Heathrow Express. Plus an increasing amount of heavy freight.

“Brunel gives us a chance to draw back from the day-to-day work to take a deep dive into the issues,” says Senior Programme Manager Anna Scannell.

“We’ve been looking at what we can fix now, but a lot of the work is trend analysis, collecting data.”

Programme Manager Andy Jackson adds: “We looked for what was missing, what the people out on the track every night could not see.

“We identified the ‘bleeders’ of performance. And the biggest bleeder was trips of the OLE [overhead line equipment]. The main cause was vegetation touching the wire, especially during windy conditions.

“We took each individual incident and gave it a priority order. Priority 1 was to fix something right now. Priority 2 was something we needed to do only after that, so we didn’t just go out and cut everything willy-nilly.

“That led to a remarkable drop in OLE trips, and that contributed to a big step-up in overall performance.”

How did Network Rail reach the point where the busiest stretch of overhead power in the country was being so severely damaged by such an obvious and well-understood problem?

“We had a long-term programme to clear vegetation back to eight metres from the wires,” Jackson defends.

“But COVID got in the way. For a long time, we could not have groups of people working together. And it doesn’t take long for vegetation to grow - it can be a metre at least in the summer season. And the line is getting busier, so getting more time on track was also becoming more difficult.”

Scannell adds: “Access is always a major issue for us. We needed additional time. We have taken an hour extra each night.

“That might not sound a lot, but it makes a big difference. We’ve taken out the last trains of the evening, and obviously that’s difficult if trains have been running late during the day. But we’ve been working with Great Western Railway, the Elizabeth line and Heathrow Express.”

“And we’ve had quite a few problems with pigeons,” adds Jackson.

What? Pigeons are seriously a major factor in poor performance on the Great Western?

“Yes. We found they were a significant cause of delay. This was my biggest surprise.

“Pigeons nest under bridges. As the train goes past with its pantograph, they get on top of the wire and form an earth to the bridge. That knocks the power out.

“We have done some targeted pest control, and it has made a huge difference. It’s a serious topic. We looked at why there were so many power trips at Ladbroke Grove. And it was an infestation of birds.”

Track circuit failures had previously been an almost daily occurrence. The circuits identify when a train is in a particular section of track.

“The axle counters weren’t coming off the rail, but they were becoming just loose enough to cause what we call ‘system drift’,” says Jackson.

“We had 777 individual assets, and we have changed them all. The last few are being done now.

“We now have a system that detects system drift and alerts the maintenance team before it becomes a fault. It’s a new system, the first in the country, and it means we can identify what has failed before we get to site, so we are there for a shorter time. It has been hugely successful.”

Improving performance

“We have reduced delay minutes by 125,000 year-on-year,” says Programme Director Karl Winstanley.

“That is a 21% reduction. I’d say that is a vast performance improvement. That’s the headline, against a much busier railway.”

Lee Joyce, who leads on track and drainage for Project Brunel, explains: “The railway saw a lot of change in a short amount of time - COVID, the Elizabeth Line coming on. We lost Red Zone access [working on track with trains running].

“And we have a 38% increase in tonnage on the tracks. If you do 38% more miles in your own car, it would need more servicing, wouldn’t it? Very broadly, 38% heavier equates to 38% shorter lifespan of the tracks. Our colleagues had not planned for that to happen.

“We have now done a lot of drainage work. The greatest problem was in the first three miles out of Paddington. The drainage system is old - Victorian in part - and we uncovered things that happened in British Rail’s time that had been lost to history.

“Realignments where drainage was covered over, for instance, which still existed but could not be accessed for maintenance, and for which there was no written record. It was detective work on the ground to work it all out. Our teams out doing maintenance would not have been looking to see whether a drain had been designed correctly.

“And some overhead line masts have gone through some of those drainage channels. That was done 15 or 20 years ago. So, we’ve had to take a holistic approach to sorting it.”

A particular problem is what track engineers call “wet beds”. Water becomes trapped in track ballast and drains more slowly than it should - or not at all.

Jackson explains: “Water and contaminated sludge is trapped in the gravel, and eventually leads to the gravel having to be replaced. It gets to a point where you have a wet paste, which you have to dig out.”

The project has required a larger number of maintenance workers.

“We’ve had a bit of a challenge there,” says Joyce.

“A lot of the work is not 9 to 5. A lot is at night. There has been quite a recruitment drive, but we are there or thereabouts now.

“And we have implemented sandpit training.”

I beg your pardon? You’ve put recruits in a sandpit, like children at a primary school?

“That’s exactly how we describe it. That’s what it’s meant to reflect - getting new people in and trained safely. Rather than getting them out on site straight away to learn on the tools, we now have dedicated areas off track with things like points set up, where we can get competence up quicker.”

Business as usual

“Part of the Brunel longer-term will be to see how that changes with climate,” says Joyce.

“We haven’t got to that stage yet. There’s a lot of work to map interlinked drainage systems. We have to map the flow capacity of every catch pit, including ones that are missing or were covered over in British Rail days.

“We need to work out how suitable that drainage system is for changing times. We have to look at resolving these systemic design issues.”

The Project Brunel team is not large - most members were sitting round the meeting room table in Reading, with space to spare. Ten people, in all, although each has what they call “dotted lines” to the contractors carrying out remedial work.

“We are now into the ‘Sustain’ phase, which means moving from the recovery work we have done into becoming business as usual. We have to keep that up for the long term,” says Winstanley.

Jackson adds: “We are taking out failure points. It’s about making what we’ve done so far a culture change, to bake in the improvements.

“For example, we brought forward a five-year programme of inspections of the overhead line equipment.

“Hook-and-eye linkages, weights, isolation switches. And line guards, which is what we use to stop chafing in high winds. They won’t necessarily foul when they do that, but over a period of years it reduces the life of the kit, so we are putting in more line guards to increase the life of that piece of infrastructure.”

What will success look like?

“Sustaining what we have achieved so far, and improving rather than declining,” replies Joyce.

“Some is about the metrics,” adds Winstanley. “Some is about perceptions. We want people to feel the service is more reliable on the route.”

Joyce suggests that “at a small level, Project Brunel is almost a precursor to how Great British Railways will work”.

He explains: “We are building better and stronger relationships. It is all about the train operators working with us to create the space where this work can be done. We are all doing what is best for the system, rather than for one part of the system.”

Jackson adds: “What sticks out for me is that everyone wants the same thing. We’ve had to look above our own specific disciplines and look at it as a system.

“I’m from signalling, Lee is from track. The maintainers want to do a better job, the train companies want more reliability. There has been no opposition to what we are all doing.”

A passenger perspective

“The real problem is that the level of delay some weeks is unacceptable, and shows little sign of improvement,” commuter Jason Stuart tells RAIL.

Stuart lives outside Newbury. He commutes from the Berkshire town two or three days a week to Canary Wharf, where he works in finance.

“It is great that we have seen so much money spent electrifying the line to Newbury, new trains, and a station upgrade that could not have been better.

“The one thing we really wanted was more trains on time. Far too often that is not the case. Typically, delays are between 15 to 30 minutes, with some trains cancelled.

“It always seems to be points, signals and track defects. The daily Travelcard costs £87.40, with parking at the station another £7.50. For 40 minutes each way to Paddington and another 20 minutes on the Elizabeth line.

“It really isn’t good enough for how much we pay.”

Steve Smith, of the Bedwyn Trains Passenger Group, notes: “We are delighted the industry is taking the problems seriously, but any promise of ‘things will get better’ is met with scepticism.

“The passenger focus is for trains to be on time with seats available. There is still room for improvement. The evening direct trains to Bedwyn are running at 40% on time. The morning trains are better, but there are still regular cancellations.

“When Project Brunel was announced, we did email our members. But things quickly get forgotten and any cancellation or delay is met with cynicism.”

A train operator perspective

“If these 35 miles of infrastructure aren’t run effectively, the ripple effects are felt by customers as far afield as Swansea, Bristol, Penzance and Worcestershire,” says GWR spokesman Dan Panes.

“We’ve given Network Rail extensive additional access to the infrastructure to allow them to focus on these critical improvements. While this has had some impact on our customers, it underscores just how crucial reliability is, and we are now starting to see the benefits.

“The work on axle counters and overhead line resilience has been particularly notable, but what we’re really seeing is an increased level of detail in planning and execution that wasn’t always the case before.

“That said, improvements always need to happen faster and on a greater scale. While we’re seeing positive early signs… passengers want the railway fixed today.”

For a full version of this article with more images and data, Subscribe today and never miss an issue of RAIL. With a Print + Digital subscription, you’ll get each issue delivered to your door for FREE (UK only). Plus, enjoy an exclusive monthly e-newsletter from the Editor, rewards, discounts and prizes, AND full access to the latest and previous issues via the app.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.