Greg Morse considers the incident at Nuneaton in June 1975 that claimed the lives of six people, and how the industry continues to focus on preventing any repeat.

In this article:

Greg Morse considers the incident at Nuneaton in June 1975 that claimed the lives of six people, and how the industry continues to focus on preventing any repeat.

In this article:

- In 1975, a Glasgow-bound sleeper derailed at Nuneaton after failing to slow for a 20mph speed restriction.

- The key warning board's gas-lit speed indicator had failed, and no prior train crew reported the outage.

- The tragedy led to stronger safety measures, including broader use of AWS, though overspeed incidents still occur today.

You live in London. You have business in Glasgow. Not for you the lure of the domestic flight, with its promise of speed.

Trains are fast enough, and you were impressed last year with that run in one of the new ‘Electric Scots’ (RAIL 1009). Why not take it easy, and get your head down on the move?

You’re still saving money on hotel bills, and can still do some last-minute work preparation on the way.

And so, in fiction, you find yourself at Euston late on a Thursday night. You have a nightcap in the bar and board to wait for the off.

In reality, it is June 5 1975 and the train is the 2330 Euston to Glasgow.

Departure came ‘right time’ that night, with 86242 taking its train of 12 sleeping cars, two brakes and a buffet out of the station and up Camden Bank towards Willesden Junction.

Some 28 minutes later, though, and the ‘86’ developed a fault and came to a stand on the Down Fast just beyond Kings Langley.

In the cab were driver John McKay and his assistant L. W. Norman. Norman had asked to drive. McKay was happy to let him. Yet when the locomotive broke down, it was Norman who went forward to protect the line and McKay who called the signaller.

‘Wait for assistance” was the instruction. So they waited for an hour (answering a toot from the driver of the 2345 Euston-Barrow, which had been routed round the failure), before 86006 arrived from Willesden and was soon hooked on.

By 0058, now into the Friday, they were on the move again, with McKay back at the controls and determined to make up time.

Between Rugby and Nuneaton, the train reached 90mph, but it was still some 66 minutes late as it approached Nuneaton…

Ahead lay a temporary speed restriction of 20mph, imposed while track remodelling work was under way.

McKay was keeping his speed steady at around 80mph. By the time the board marking the start of the restriction came into view, it was too late.

McKay ‘threw out the anchors’, but 86006 derailed almost immediately on a sharply curved section of track laid as part of the remodelling. It took all but the rearmost carriage with it, the train continuing as carriages slewed in and out, striking lineside structures as it went.

The locomotives became divided from the train and each other, with 86006 continuing until it stopped in the six-foot within station limits, and 86242 veering and mounting the platform, before becoming wedged between it and the canopy.

Two sleeping car attendants and two passengers were killed. Two more passengers later died in hospital. Thirty-eight people were injured. It was now 0154.

The signaller and supervisor on duty in Nuneaton ’box saw the scene unfold. They alerted the emergency services immediately.

Within six minutes, the police, fire brigade and ambulance crews had reached the scene. Aid also came from the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service, the Salvation Army, and other local voluntary groups.

Damage to the sleeping cars was so extensive that rescue operations would take several hours - the last casualty was not freed until 0739.

Searches continued among the twisted metal until 1145 on Sunday June 7, when it was finally confirmed that no one else was trapped.

The Railway Inspectorate (RI) launched an investigation, led by Major C. F. Rose, who had been commissioned in the Royal Engineers in 1947, and who would serve in Palestine, Korea and the Laos-Vietnam border at the height of the Vietnam War. Ahead of him lay a stint (from 1982) as the RI’s Chief Inspecting Officer.

His report revealed the full picture, going into great detail about the speed restrictions imposed on the Nuneaton area. They had been in place since midnight on Sunday May 25, during work on the ninth stage of a wider remodelling scheme which had been in progress since the start of the year.

Restrictions such as this were usually passed on to drivers via the Weekly Engineering Notice, a printed document sent to depots, stations, offices and messrooms. They usually appeared on a Tuesday or Wednesday, for distribution on the Thursday. Each member of train crew received their own copy.

On the ground, the restricted section of line was marked by a ‘Speed Indicator’, with black numerals on a white background showing the maximum permitted speed.

The end of the restricted section was marked by a corresponding ‘Termination Indicator’, featuring a black ‘T’ on a white square background. Both of these signs were paraffin-lit.

To give advance warning for trains to start slowing to the mandated speed, a ‘Warning Board’ was erected. Back then, this was a yellow ‘arrow’ pointing to the track, with two white gas-lit ‘bulls-eye’ lamps set in. Above this would be a sign showing the speed limit relating to the coming restriction.

The weekly notice relevant to this case had been issued at Crewe on May 20. The item about Nuneaton specifically confirmed the warning boards for the 20mph restriction to be lit by propane gas for the “reballasting and relaying [of] points and crossings”. The restriction was to be in force “until further notice, unless otherwise specified”.

When interviewed by Rose, Assistant Permanent Way Supervisor (APWS) Batkin, who was in charge of the Nuneaton remodelling, said that he had observed a number of trains passing through the area during the ten days since the speed restriction had been implemented.

He thought some of them exceeded the limit by about 5mph, but noticed “no undue movement” of the temporary track section and thought it would be safe up to 40mph.

The boards had been put out under the direction of APWS Evans. The Warning Boards for the Down Fast had two 42lb gas cylinders. Evans had checked both. They were fully charged, and their seals were unbroken.

The correct procedure was to have both cylinders on, supply being taken automatically from one to the other when the first lost pressure.

But Evans said it had been the local practice to turn one cylinder on only, and for the switch between cylinders to be made manually by the patroller when the gas was judged to be running low.

This method, said Evans, had been adopted since the current design of Warning Board had been brought in (about eight or nine years, by this point). He “knew of no occasion when a lack of gas had led to the lamps on a Warning Board becoming extinguished”.

The patroller - D. Costello - told Rose that in the ten months since he had started working in the Nuneaton area, no one had ever told him to do anything other than use the method Evans had described.

Costello checked all lamps during his usual rounds, which took place on this section of line every Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday.

On Sunday May 25, he topped up the paraffin in the Speed and Termination boards. On Wednesday June 4, he checked the Warning Board on the Down Fast twice. Both times, “the lights were burning well”.

Costello’s immediate superior was Track Chargeman Merrick. At about 1100 on June 5, he was walking along the line to Nuneaton when he too saw that the three lamps on the Down Fast Warning Board were clear and bright.

Like Evans and Costello, Merrick followed the ‘one cylinder’ method, knew of no other, and knew of no case where the lights in a board had gone out due to a lack of gas.

But that is exactly what he and an Inspector found soon after the accident. The mantle of the lamp behind the ‘20’ indication was broken, with only the bottom part still attached to the burner.

One of the two ‘bulls-eye’ lamp mantles had a hole in the top. There was a strong smell of gas and a very faint hissing sound. Merrick turned one of the cylinder valves off and the hissing stopped.

D. E. Morris, Senior Technical Officer at Crewe, had been worried about the use of propane lamps for six or seven years. He knew all the lamps on his patch had the automatic changeover facility. He knew too that the ‘one cylinder method’ was being used on point heating equipment. He had his suspicions about Warning Boards.

Examination revealed that the cylinder connected to the lamps was almost empty, while the other was full. It also found that the changeover valve was in working order and would have functioned as designed if the equipment had been set up correctly.

Between 2223 on June 5 and 0058 the following morning, 15 trains had passed through Nuneaton on the Down Fast.

All observed the speed restriction correctly (“or close to the correct speed”). Six of the crews said the ‘20’ on the Warning Board had been out. Of the other nine, four said it had been bright, four said it had been dim, and one professed not to have noticed. Everyone agreed that both ‘bulls-eye’ lamps were lit, although opinions differed as to their brightness.

This all added up to a situation whereby the ‘20’ had probably been out since about 2230, but the ‘bulls-eyes’ had been giving adequate light until about 0058. This highlighted in turn a failure to follow the Rule Book.

In 1975, Rule T.25.5 stipulated that if a driver saw that any light at a Speed Indicator or Warning Board was out, the signaller needed to be advised. If, on a Warning Board, one ‘bulls-eye’ and the speed lamp were still on, or both ‘bulls-eyes’ and not the Speed Indicator, this could be reported “at the first convenient opportunity”.

None of the drivers who had noticed the ‘20’ being out made such a report.

But between 0059 and the accident, four more trains passed through. The last had been the incident train. The first had been the 2345 Euston-Barrow. Its driver noticed that the ‘20’ was out, but while the two ‘bulls-eyes’ were on, they were “distinctly dimmer than he had seen them on previous nights”.

The driver of the next train, the 2330 Kensington-Stirling Motorail, saw that none of the lamps were lit. But as he had been expecting the restriction, and as he caught a glimpse of the unlit board, he reduced speed and passed through the restriction without incident.

The third train was a Willesden-Runcorn freight. Its driver insisted that all three lamps on the Warning Board had been lit.

Rose pointed out that this contradicted the evidence of the Motorail driver, and suggested that the freight driver had confused the Down Fast Warning Board with the one for the Down Slow.

The freight driver insisted otherwise… until withdrawing his statement after the public hearing, saying that after seeing a green signal some 300 yards before the board, he had been checking in his bag for his handlamp and had missed the board completely. No explanation for his previous insistence was ever given.

When Rose spoke to Driver McKay, he learned that McKay had received the notice of speed restrictions through Nuneaton on Saturday May 24, but did not drive on any of the Down lines between Rugby and the station until the night before the accident.

That night, he had taken the 2300 Euston-Glasgow as far as Crewe. That night, all three lamps on the Down Fast Warning Board had been lit.

McKay observed the restriction correctly and felt the train lurch as it traversed the temporary section of track. It felt, he said, “unusual, but not particularly alarming”.

The following night he took the same train over the same route. He described the locomotive failure, that he then had time to make up, how he kept the controller open.

He saw the illuminated Warning Board on the Down Slow, but nothing on the Down Fast. He told Rose that he realised the restriction on his line must have been lifted. He convinced himself the board must have been removed. He was wrong.

Rose concluded that the light in the Warning Board giving the ‘20’ restriction had gone out “almost certainly due to a failure of the gas mantle”.

However, the other two lamps went out as the gas ran out and the automatic changeover device from the empty canister to a full one had not been activated.

None of the drivers who passed the board after the lights had gone out reported that fact. Had any one of them done so, the matter would have been addressed, and (arguably) the accident would not have occurred.

As for McKay, Rose dismissed the idea that he’d assumed the restriction to have been lifted.

He wrote: “I consider it more likely that, without the positive reminder given by the lights in the Warning Board, Driver McKay momentarily forgot about the speed restriction and only realised his mistake when closely approaching Nuneaton.”

He had been concentrating on driving, on making up time, and so it was “quite possible that […] the presence of the restriction at Nuneaton might have escaped his mind during the vital few minutes”.

It was decided that the problem could be solved by using an Automatic Warning System (AWS) ramp, to warn drivers of the presence of a speed restriction ahead.

This built on the use of AWS to warn of sharp curves with speed restrictions, which had come out of a derailment at Morpeth in 1969.

It seemed the ideal solution, although some felt there was a danger that using AWS ahead of sharp curves, speed restrictions and signals could lead to over-familiarity, and to a situation where a driver might reset the equipment almost subconsciously after receiving a warning.

Doing so without thinking at a ‘yellow’ might lead to the same thing happening at the ‘red’, which could lead to a Signal Passed At Danger (SPAD) and a collision.

Fear of this led Southern Region managers to resist AWS for many years, as they knew that on their busy suburban network the yellow ‘caution’ signal was very likely to lead to another, if one commuter train was closely following another at peak periods.

When the Dartford and London Bridge resignalling schemes were commissioned in the 1980s, however, the Southern found that the new layout allowed traffic to flow more freely, and that drivers were facing a marked reduction in the number of consecutive restrictive aspects.

As a result, AWS was deemed sufficient for Southern conditions after all (albeit with stronger magnets to reach receivers mounted on the underframes of the Region’s electric multiple units, as opposed to the bogies, as elsewhere on the network). Its use therefore continued to spread.

Overspeeding remains a concern for the industry, but could a ‘Nuneaton’ happen today?

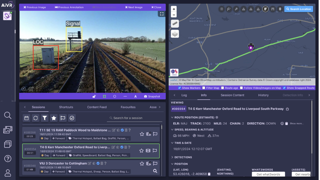

Two recent incidents at Spital Junction in Peterborough, when passenger trains did not slow for a crossover, were investigated by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch (RAIB).

In one, passengers were injured as the train lurched from one line to the other and luggage fell from the overhead racks.

In terms of effect, then, a ‘Nuneaton’ is certainly still possible.

But RAIB has also investigated a number of incidents on plain line during blanket emergency speed restrictions.

With AWS still in use for many, the emphasis is now less on the efficacy of the lighting at warning boards, but the efficacy of the methods for informing drivers about the presence of restrictions imposed to deal with unexpected events such as convective rainfall.

A cross-industry Overspeed Group is seeking to improve speed restriction management, while leading in the use and application of technologies to reduce overspeed risk. It is also aiming to improve overspeed data so that the full risk picture is clarified.

As humans, we always tend to think we know better than our forebears. But the late notice case method is still used today and the lessons of Nuneaton remain: speed restrictions are there for a reason, so they need to be properly announced… and properly adhered to.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.