Stuart Porter revisits requirements for HS2, to examine how to make optimum use of train paths.

In this article:

Stuart Porter revisits requirements for HS2, to examine how to make optimum use of train paths.

In this article:

- HS2's future could improve if costs are controlled and services adapt to new rail market conditions.

- Splitting double-length trains may increase revenue, reduce Birmingham journey times, and improve passenger convenience.

- Eight platforms at Euston are ideal for HS2’s future, but six could work with WCML platform access.

Recent assessments of HS2 are too gloomy, if costs are brought under control and HS2 introduces practical and frugal tweaks to improve its business case and reflect the changed rail market.

The East Coast Main Line is reportedly doing well, while the West Coast Main Line is in the doldrums. I am therefore not surprised that Rail Minister Lord Hendy said in mid-December: “The first job is to fix the HS2 we’re building now, know how long it’s going to take, how much it’s going to cost, and integrate it with a national railway network.”

To me, that means: fix HS2 and the associated WCML infrastructure, and then eventually consult on a long-term integrated vision for HS2 and key aspects of the HS2 service specification. Hopefully, the integration work will solve the WCML capacity issues arising from Phase 1, including Weaver Junction.

What is surprising is the interpretation (by some) of Lord Hendy’s reply to Lord Berkeley’s Commons Written Question as implying that HS2 Euston might be limited to six platforms in perpetuity. I don’t share that interpretation as, just before a parliamentary break, replies are often ‘straight bat’ comments rather than nuanced.

Six platforms and future access to four WCML platforms would be a better outcome, as William Barter argued in a letter in RAIL 1024. That could allow for HS2 services going beyond Birmingham and Manchester, and reduce the notorious Euston platform dash by providing 35-minute turnarounds.

But it requires passive provision for adjustments to WCML (or HS2) track levels in their parallel Euston throats, and the third crossover tunnel which was in HS2’s Hybrid Bill plans.

Planning of HS2 Phase 1 was rushed, with costly decisions taken after the plans were finalised, rather than as part of finalising them. Any Phase 2 needs to be nailed down first to avoid repeating the same mistakes.

This seems to accord with other comments that “HS2-light has been mothballed [by] government officials UNTIL [my emphasis] Phase 1 to build a high-speed railway between London Euston and Birmingham has been delivered”.

As a transport economist planner who commuted on the Midland Main Line for 12 years, I have experienced the now permanent scheduling constraints which arose when St Pancras lost two MML platforms to accommodate Eurostar.

I have set out below my long- and short-term vision for HS2 to complement my RAIL 1023 comments, which advocated a way forward for the former eastern arm communities in the 2050s, should passenger growth return.

Key opportunities

Opportunities to generate extra revenue arise, now that a scaled-back HS2 has spare train paths. For example, some of HS2’s planned double-length trains could be split, making half of them quicker at prime times.

Such a strategy can cost-effectively increase frequencies to Lancashire and reduce journey times to Birmingham Curzon Street by up to ten minutes compared with HS2’s plan.

It would allow Birmingham Interchange services to serve a wider range of destinations, rather than being an annoying suburban call on the Birmingham Curzon Street services.

Eventually such services require at least eight Euston platforms for HS2’s use - but can manage with six if two are required as temporary access to over-station development.

Testing those ideas with both fast and semi-fast shuttles to Birmingham and Manchester at prime times (three minutes apart) could even eventually allow some shuttles to head further north (see panel, page 52). All the extra services could be demand-dependent.

These ultimate alternative commercial specifications, which fully separate HS2’s planned Liverpool and Preston services (to save passengers time and create space for Birmingham Interchange passengers), are intended to show a range of possibilities while meeting HS2’s design parameters for headways and tunnel ventilation. All the extra services could be demand-dependent.

If the Curzon Street throat can handle extra movements, these ultimate alternatives should have sufficient passenger capacity for some Euston services to progressively serve Manchester, Derby and beyond by reversing at Curzon Street.

The latter could be ten minutes quicker than Midland Main Line’s aspirations (and more crucially 50 minutes quicker to/from Heathrow and points west).

Those Derby extensions can be dependent on passenger growth returning to historic levels, justifying subsequent extra rolling stock and track upgrades (as outlined in RAIL 1023).

If, on the other hand, the Curzon Street and Euston throats cannot handle enough extra movements, some services could take at least four minutes longer to divide/join at Birmingham Interchange etc.

The illustration in the panel, with departures to Leeds and beyond, would serve Heathrow and points west well and capture the Heathrow extra saving (discussed above) for a wide range of destinations.

It would also provide welcome relief services during disruption on the ECML, using 16 or 17 of HS2’s planned 18tph line capacity, if passenger demand justifies everything.

Step-by-step service build-up would minimise risk, limit operating costs, and allow other tweaks if reliable capacity is more limited than predicted. It would optimise revenue, passenger capacity, and their experience.

Reliability

The reliability implications of that intensive use would need to be confirmed by incremental operational experience and/or probed by experts.

HS2’s design parameters are that every ten minutes, three trains would be scheduled at three-minute intervals.

Tunnel ventilation spacing and design speeds have been chosen to meet those parameters. They leave one-minute recovery time every ten minutes and imply any single late-running train probably delays three other on-time services by one minute.

Reliability is also affected by responses to incidents and disruption during planned maintenance.

As some Old Oak Common provisional ideas could eventually require weekend works, it would be prudent for electrical installations to allow single-tunnel operations of shuttle services.

Four flighted trains per hour could provide a usable shuttle service to Old Oak and Birmingham Interchange of 64 coaches per hour in each direction for onward connections.

Similarly, low-speed battery-powered fallback arrangements to bypass any electrically dead sections are worth considering, if they are not already part of the design. Introducing each improvement incrementally and provisionally should also contribute to long-term reliability.

If sufficient platforms cannot be provided at Euston, one could perhaps accept occasional delays by deliberately holding back some arrivals to create a virtual spare platform during unexpected platform blockages.

It would, however, be better to free some WCML platforms.

For example, if passenger growth is extreme the high-frequency London Northwestern Railway Milton Keynes-Euston service could be diverted below Euston to Gabriel’s Wharf, with entrances via Waterloo East and Temple stations.

Serving Waterloo was the original intention for Crossrail 2. Any such tunnel could be shared by suburban King’s Cross services to increase its platform capacity - with open access operations moved to King’s Cross suburban platforms.

That drastic example could be required if all the current open access applications are successful.

For example, Virgin Trains would like to be allocated the empty train paths currently not needed by Avanti, and one could speculate that might result in WCML services being ultimately divided between HS2 and Virgin Trains with publicly supported services only being provided by the equivalent of London Northwestern Railway.

Beyond Birmingham

HS2’s eastern arm plans improved capacity to London and speeds to Leeds and Heathrow as well as points west to/from the ECML. Those Heathrow benefits exceeded central London savings by 40 minutes and are still achievable by extending HS2 services beyond Birmingham or Manchester. That differential applies equally to MML and WCML locations.

Extensions beyond Manchester would be easiest, but capacity on that route is limited even with double-length platforms at Manchester and Old Oak extra services.

Thus, it would be better to eventually plan to spread the load and to take advantage of potential passenger capacity to run double-length services to Curzon Street, part of which then reverse there. Extending either requires the reallocation of most Birmingham Interchange calls away from the Birmingham Curzon Street services.

Ultimately, such services could serve Derby and beyond ten minutes quicker than the MML’s aspirations. The necessary rolling stock orders could be provisional and timed to optimise that relief, in the light of MML passenger growth and HS2 experience (RAIL 1023).

Meanwhile, a fast electric (MML or HS2) train every 15 minutes ex-Derby to Sheffield, Leeds and beyond seems feasible, and could be introduced early north of Sheffield by extending MML services to Leeds and co-ordinating timetables.

The whole package would avoid the increasing unreliability caused by Thameslink trains crossing the MML lines, although some local services might need to use the Barrow Hill Goods Line to avoid overloading Dore to Sheffield.

Old Oak

If more Birmingham shuttles need relieving, their relief services could start from one of the central platforms at Old Oak and still use the empty spare paths ex-Euston.

As extensive use of those central platforms could require passive provision for Old Oak tunnelled sidings, it would be prudent to establish a range of possibilities.

Most potential passive provision for such sidings need limited tunnel throat widening and the retention of the Atlas Road service tunnel.

If sidings are justified, the possibility of extending them to Camden Road and HS1 stations in the 2070s could also be considered. That should maintain HS2’s environmental ambitions by diverting and enhancing the planned Camden High Line linear park.

Conclusion

Avanti’s West Coast Partnership was supposed to review and comment to the Department for Transport and others on HS2’s “illustrative Phase 1 and Phase 2 timetables”, but that is rightly not yet seen as a priority. I hope this article fills that short-term gap by producing alternative ‘illustrative’ commercial aspirations.

The maximum aspirations envisage some absolute peak relief services starting or ending at Old Oak (initially to maintain eight-coach operation for longer).

Doing that would lessen the threat of overloaded services at Old Oak, which 25% of HS2 forecast passengers prefer as their interchange rather than Euston.

Any such paired services could be seamlessly recombined at quieter times of day, or during some driver shortages.

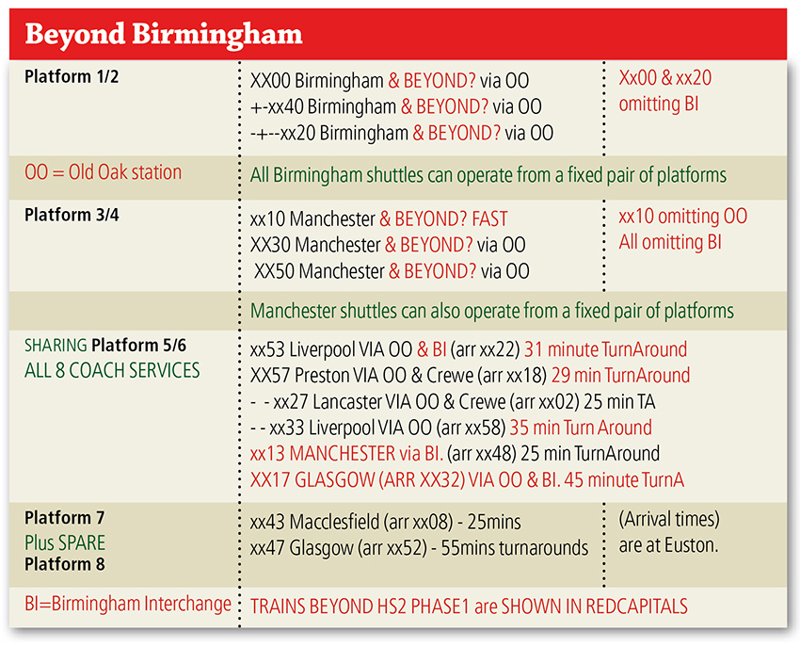

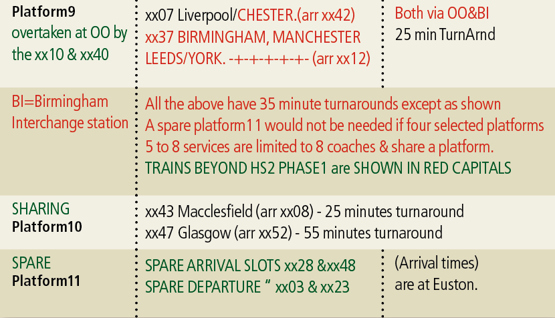

Now that ministers say the primary focus is the completion of HS2 Phase 1 between London and Birmingham “at the lowest reasonable cost”, the following would be an initial eight-platform ideal.

It speeds up both Manchester and Birmingham shuttles by adding two extra services and withdrawing most Birmingham Interchange calls on the Birmingham Curzon Street services.

Services beyond Birmingham should include Glasgow and Leeds via Stoke and Manchester, replacing WCML and trans-Pennine services.

Platform sharing could be reduced by extra platforms, or delaying the introduction of 35-minute turnarounds, which is needed for fixed pairs of shuttle platforms and reducing the Euston platform rush.

Delaying that might not be needed if the spare platform is only needed infrequently. In that case, one could retime the Platform 7 services to replace the Platform 5/6 red services and plan for the Manchester and Birmingham shuttles to be held for seven minutes at Old Oak whenever a spare platform is needed.

That would create a virtual spare while the other services use the other Up Old Oak platform.

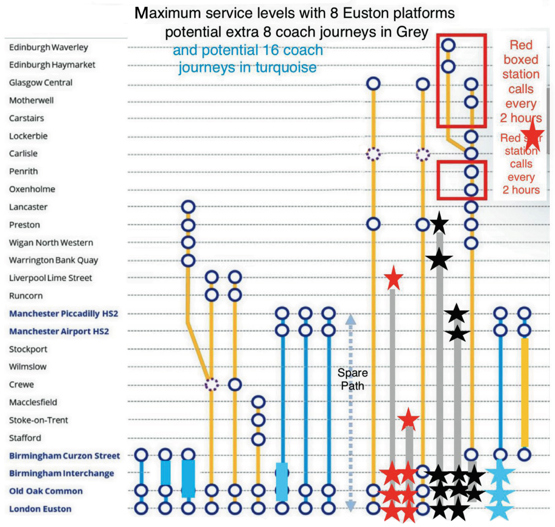

HS2 Western Arm Phase 2 illustrative timetable

HS2’s ‘illustrative timetable’ (belowt) has been annotated to show an optimistic eventual ambition. That potential alternative commercial specification can fit onto ten HS2 Euston platforms, or eight with platform sharing.

The optional extra eight-coach journeys are shown in grey and are designed to provide better connectivity to Birmingham Interchange and to allow faster journeys to Birmingham Curzon Street.

Early phases of that alternative could even manage with six or seven platforms at Euston. But ultimately it would be preferable if there were ten HS2 Euston platforms to avoid platform sharing (with two trains sharing some platforms at the same time), and to provide extended turnarounds for more longer-distance services.

If sufficient platforms are available at HS2 Euston, the Glasgow services could potentially serve Edinburgh as originally intended by dividing at Preston or Carlisle, and eight-coach services could be longer.

A slight variant is shown in the provisional platform allocation chart (below). It allows for services going beyond Birmingham and Manchester, and provides 35-minute turnarounds (except as shown) to help reduce the notorious Euston platform dash.

That ten-minute increase in turnarounds (compared with HS2’s plans) allows the key shuttles to be concentrated on paired platforms (instead of three rotating platforms), but does require some platform sharing or 10 +1 spare HS2 Euston platforms. Other variants are possible. Services beyond HS2’s illustrative Phase 1 are shown in red capitals.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.