To mark the 80th anniversary of VE Day, Richard Foster presents an overview of how the railway responded to the nation’s First and Second World Wartime needs.

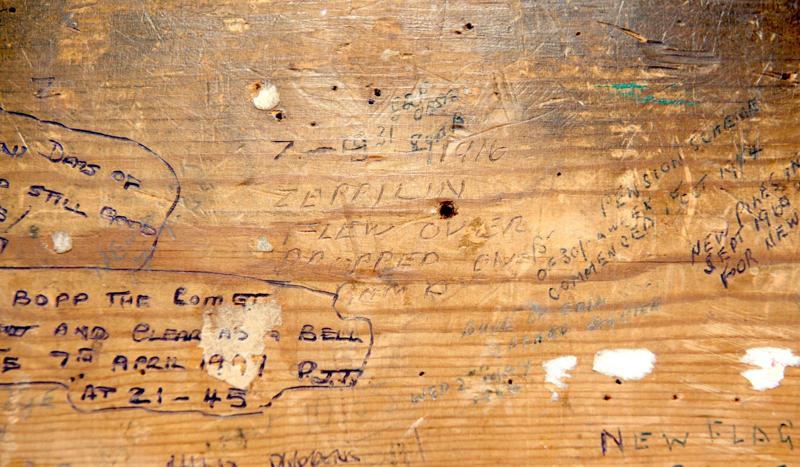

It’s the night of April 15-16 1915. The signalman on duty in Oulton Broad ‘box is so overwhelmed by what he is seeing - bombs falling on the nearby Suffolk coastal town of Lowestoft - that he feels compelled to record it somewhere. So, he scratches it onto the desk that holds the train register.

To mark the 80th anniversary of VE Day, Richard Foster presents an overview of how the railway responded to the nation’s First and Second World Wartime needs.

It’s the night of April 15-16 1915. The signalman on duty in Oulton Broad ‘box is so overwhelmed by what he is seeing - bombs falling on the nearby Suffolk coastal town of Lowestoft - that he feels compelled to record it somewhere. So, he scratches it onto the desk that holds the train register.

It’s often forgotten that the Germans did bomb Britain during the First World War. Just over 100 such raids took place between 1914 and 1918, and 1,414 Britons were killed.

By contrast, the Germans killed 430 Londoners on September 7 1940 alone, and a further 1,436 on the night of May 10-11. In fact, the 1940-1941 Blitz killed some 43,000 people across the country.

This highlights the key difference between how Britain was affected by the two global conflicts that changed the course of history in the 20th century.

The First World War was (the occasional air raid aside) primarily fought on the continent. No different perhaps to the colonial wars that Britain had been fighting.

But the Second World War brought the conflict into people’s back gardens.

Britain’s railway did feel the effects of war. Manpower shortages resulted in some 68,000 women being employed by the railways, while uneconomic stations were closed. Coastal lines were patrolled by armoured trains.

The railways had been nationalised on August 4 1914, the day that Britain declared war on Germany.

Centralised control, which has been planned for since 1912, had to co-ordinate with moving men and materials to ports - particularly the new roll-on-roll-off terminal at Richborough, in Kent.

It had to deal with hospital trains bringing in unprecedented numbers of wounded personnel.

And it had to solve the logistical issues caused by the arrival of US troops in 1918.

But it was placing the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow, in the Orkneys, that caused a particularly acute headache.

Coal from South Wales was moved to Grangemouth on special trains - an operation which at its peak amounted to 109 trains a week.

The Highland Railway, whose main line from Perth to Inverness and beyond was largely single track, also struggled to cope with the demands placed on it by the Royal Navy.

But the railways had to cope… and passengers could no longer expect the same levels of service that they had before 1914.

The infamous Quintinshill disaster of May 22 1915, which killed 200 (many of them servicemen destined for Gallipoli), illustrates the perils of running a railway under wartime conditions.

The Second World War brought many of the same issues, but with some significant curveballs thrown in for good measure - Operation Pied Piper (the evacuation of children), Operation Dynamo (the rescue of the British Expeditionary Force), and Operation Overlord (the Allied Invasion of Europe).

Operation Pied Piper was the largest mass movement of people in the British Isles, and it was the result of developments in air power.

Gone were the flimsy aircraft and airships of 20-or-so years earlier. The Germans had fast, sophisticated aeroplanes. Britain was trying to catch up, but the devastating effect of the Luftwaffe had been witnessed during the Spanish Civil War.

It was anticipated that bombs would start falling as soon as war was declared. Therefore, at 1107 on August 31 1939, with Hitler’s troops massing on the Polish border, ‘Pied Piper’ was put into action.

The children involved viewed this either as an adventure or as the most traumatic event of their young lives. Some described the trains as ‘hellish’. Others were unable to see through the tears.

Trains actually ran on September 1-4, mainly from London but also from towns in the South East and the industrial and ‘port’ cities across the UK.

To give an example of the logistical effort involved, the Great Western Railway arranged for its Down Relief Line from Ealing Broadway to be given over solely to evacuation trains. It provided 50 rakes of 12 coaches - about 40,000 seats.

Railway staff had to deal with other ARP (Air Raid Precautions) initiatives. Station gas lamps were blacked out, footplates were hidden as much as possible, and hoods were fitted to colour signals making them almost impossible for crews to see. Passengers had to deal with stations that lacked running boards, the platform edges being marked by a white line.

Things got worse when the bombs started falling. Trains made tempting targets and had to find refuge at every opportunity - including deep inside the Severn Tunnel.

Some were stopped en route, with passengers evacuated to the nearest shelter… which could have meant some walk.

Railwaymen, with their numbers now bolstered by female employees again, had to carry on. If a town was under attack, trains would be backed up waiting for the all-clear. Firemen would be tasked with topping up the firebox of the lead locomotive and working his way down the convoy, before starting at the head again.

Footplate crews worked long hours, scrounging tools and equipment wherever they could find them, struggling with locomotives that needed maintenance.

Staff were to remain at their posts until bombers were in sight, and then had to find shelter as best they could. Sadly, two railwaymen were killed while hiding in a firebox at Nine Elms, when the locomotive received a direct hit.

The railways were once again under central control, with the Railway Executive Committee having come into force (again) on September 1 1939.

From its newly created offices in the disused Down Street Underground station, the REC not only co-ordinated how the railways would move the 338,000 Allied troops rescued from the northern French beaches, but also the preparation for D-Day - June 6 1944.

Again, as the famous wartime posters asked, passengers and general cargo had to play second fiddle to important materials.

But it’s no exaggeration to say that D-Day and Operation Overlord would not have been successful without Britain’s railway network, with sleepy branch lines such as the Didcot, Newbury & Southampton Railway turned into double-track main lines, sometimes overnight.

Perhaps the lady that GWR fireman Harold Gasson describes in his book, Firing Days, would not have minded sharing the bus with dirty enginemen, travelling to manage locomotives on busy worksites, had she known just what those railwaymen were building… a supply line to deliver Europe from tyranny.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.