Ministers appear to have backed the latest open access deal guaranteeing private operation within a nationalised railway. Peter Plisner analyses the latest news and the state of play.

In this article:

Ministers appear to have backed the latest open access deal guaranteeing private operation within a nationalised railway. Peter Plisner analyses the latest news and the state of play.

In this article:

- The UK government is renationalising South Western Railway in May 2025 while supporting open access private train operations.

- Open access operators, like FirstGroup, are expanding services despite challenges.

- Labour's rail reforms aim to maintain open access under stricter oversight, blending nationalisation with private sector competition.

At the beginning of December, just five days into her new job following the departure of Louise Haigh, new Transport Secretary Heidi Alexander announced that in May 2025 South Western Railway would be the next privately run operating company to be renationalised.

As part of the announcement, she spoke of private companies presiding over a “broken railway”.

Regardless of your view on whether or not the railway is broken, the expectation during the election was that the railway would be brought under public ownership to fix it.

Legislation to enable that to happen gained Royal Assent in December, and other franchises - including c2c and Greater Anglia - will also be brought under what is now being called ‘DfT Operator’ during 2025.

Previously known as DfT OLR Holdings Limited (DOHL), it is already running four previously franchised operations - LNER, Northern, Southeastern and TransPennine Express.

Yet just two days after Alexander’s announcement, the government gave the strongest indication yet that private operation within the railways is set to continue long after renationalisation.

On Friday December 6, Alexander and Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer attended an event at Hitachi’s Newton Aycliffe train building factory.

The company was celebrating after securing a £500 million order from Angel Trains for 14 Class 800 units.

The new rolling stock will enable FirstGroup to significantly expand its open access portfolio, being used on its latest route from London to Carmarthen (acquired from Grand Union) and on existing Hull Trains operations.

Some have already questioned why the Prime Minister was at the factory for the announcement. After all, this was a private train leasing company announcing a deal with a private train builder on behalf of a private train operator.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves took to social media, stating that: “Labour is protecting jobs, supporting industrial heartlands and boosting rail services. We made a promise to the workforce of the Newton Aycliffe factory - and today we have delivered on that promise.”

Responding to enquiries on government involvement in the deal, HM Treasury stated that it was a Department for Transport matter.

The DfT, in turn, directed callers to a press release on the 10 Downing Street website, headlined with the words “Government helps deliver a train-building deal that will give Hitachi’s Newton Aycliffe site a future.”

Later in the release, it was suggested that: “The Government has delivered meaningful engagement, a stable economy, and a proper strategy for rail, which has created the right atmosphere for this deal to happen.”

It went on to say: “It proves the pipeline for orders is strong, with a number of operators in the market for new trains providing contract opportunities for all UK rolling stock manufacturers.”

Clearly, government involvement in the deal was minimal, and some have seen the appearance of the Prime Minister and the publicity that accompanied the visit as blatant political opportunism.

Nevertheless, the event appears to show that ministers are happy to associate themselves with private train operators.

That has led some rail observers to conclude that even before the full scale of the reforms being planned have been published, open access operations on a nationalised railway appear to be here to stay - and that (initially at least) the “pipeline for orders” mentioned by the Prime Minister is most likely to come via private train operators.

So, if open access is here to stay, then the next big question is: how will that sit within the nationalised railways?

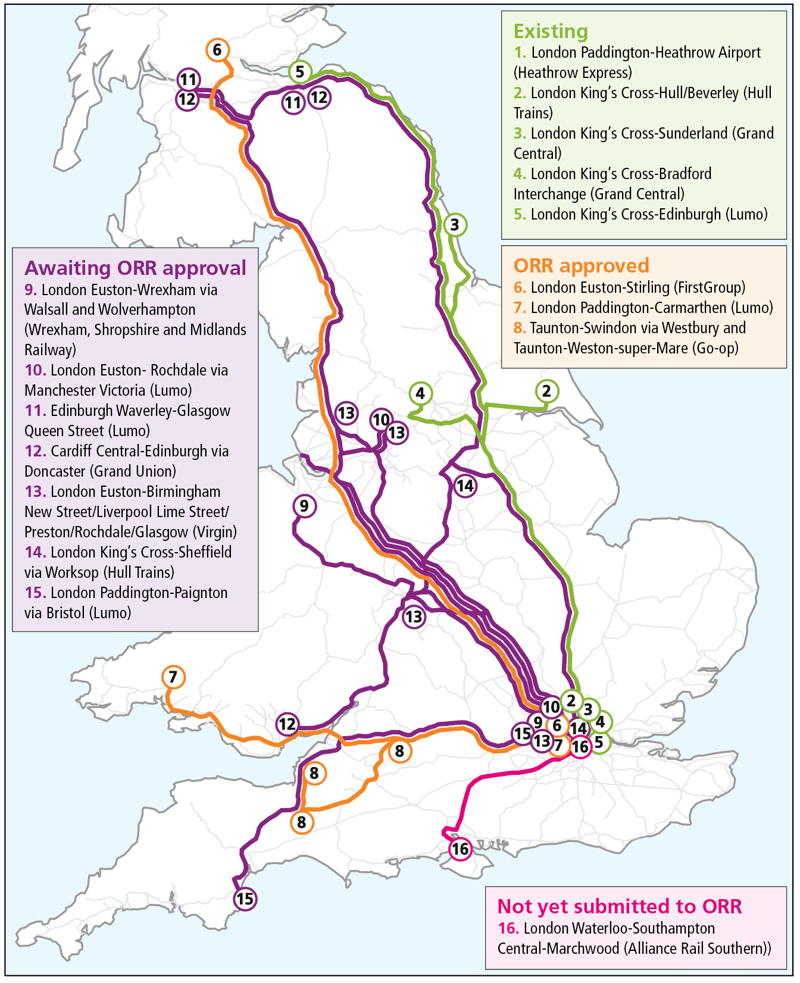

FirstGroup has made no secret of the fact that it wants to expand its open access offering. It has now acquired rights to run from both Stirling to London and Carmarthen to London.

Both services are likely to run under its Lumo brand. But Lumo itself is expanding, with applications to run from Paignton to London via Bristol, from Rochdale to London via Manchester, and between Glasgow and Edinburgh. Its Hull Trains service to London has also applied to run from Sheffield via Worksop to the capital.

Indeed, should these applications be successful, the company has committed to a further order of Class 800s, worth a further £460m.

FirstGroup Chief Executive Officer Graham Sutherland said: “We know that growth and innovation are key for the future of the railway sector, and we are committed to working with government and all our partners to provide competitive, sustainable and improved services.

“Successful open access services can provide new connections, add capacity, support local businesses and suppliers, secure jobs, and help to drive social mobility and future economic growth.”

There are currently a record number of open access applications waiting for approval by the Office of Rail and Road (ORR).

For FirstGroup and others, you do have to ask the question: what’s in it for them?

Unlike under the previous franchised railway, open access operators take all of the revenue risk when it comes to ticket sales, and receive no subsidy from the government to run services.

But it’s clear that some (if not all) open access operations do abstract passengers - and therefore revenue - from existing services.

Although ORR rules do allow for a certain amount of abstraction, that will affect what will be government-run renationalised and therefore taxpayer-funded services.

Indeed, ORR’s own assessment of abstraction on the Carmarthen-London service suggests a figure (after track access charges) of £17.6m - predominantly coming from Great Western Railway services.

Current ORR guidance requires that a ‘Not Primarily Abstractive’ (NPA) test is the key criterion used to evaluate this trade-off.

The guidance states that the NPA “informs whether new revenue expected to be generated is sufficient to compensate for the impact on the Secretary of State’s funds” - in effect, taxpayers’ money.

It further states: “Our policy is to reject applications that generate less than £0.3 of new revenue for each £1 of net revenue loss to taxpayers. Conversely, passing this test at a level above £0.3 is a necessary, but not sufficient, criterion for approval, as we must consider all factors and ORR duties together.”

In addition to the NPA test, ORR guidance also sets out that it may decide to decline an open access application if it is deemed that the absolute level of revenue abstraction is too great.

Companies such as FirstGroup have been at pains to point out (quite rightly) that when introducing a new service, they grow the market for everyone.

FirstGroup’s Managing Director of Rail, Steve Montgomery, speaking recently on the Green Signals Podcast, said: “We don’t have any concerns about doing a proper study on abstraction and making sure that it is new business that we’re going to bring to the railway.

“You meet the criteria - one in three, and all these different things. There is now new evidence from Lumo, which has made people look at things differently. There is no doubt about that. And I think the ORR would say that as well - that the abstraction test of old is something that they would maybe look at in a different light now, by what they’ve seen from different operators that are now doing open access.”

Part of the abstraction argument takes in what is referred to as ORCATS (Operational Research Computerised Allocation of Tickets).

It’s effectively a legacy from the old British Rail days, when it was used for real-time seat reservations and revenue sharing on tickets between different train operators.

Some consider that the system, which is still in operation, is past its sell-by date. However, its continued existence is helping to boost the coffers of open access operators, by providing what some consider is a government subsidy by the back door.

Twice a year, when timetable changes are introduced, the ORCATS system calculates the probability of passengers travelling on particular train services.

The system is run by Rail Settlement Plan, and uses base revenue forecasts for different days of the week and different nodal points across the network, and on most (but not all) ticket types, and for peak and off-peak services. It is there to share out the revenue between routes where there’s more than one operator.

Under British Rail, ORCATS worked fine because (effectively) it acted as a money-go-round between different government-funded train services.

Even under privatisation, it helped to balance things up where services needed subsidy from the government.

But when it comes to open access, the ORCATS system effectively gives that same money to the private operators.

ORCATS does its calculations using only the timetable. It doesn’t take into account how many carriages or seats there are on a particular service. This means that a train operator running a five-car train gets the same share of the ticket revenue on a route where another operator might be running a ten-car train.

Ian Yeowart, one of the most prolific exponents of open access, says issues over abstraction and ORCATS are old arguments.

Back in 2006, he won open access rights for his company Grand Central to run from Sunderland to London’s King’s Cross. He says: “There is 25 years of evidence. On the one route where there is real head-to-head competition, which is Lumo between Edinburgh and London, the entire market has grown, so LNER actually carries more passengers than it did before Lumo arrived. That’s not a coincidence, is it? Everywhere else in the world where competition arrives, the market gets better.”

If not monitored carefully, the system is clearly open to abuse, and has led in the past to what some have referred to as an ‘ORCATS raid’, where it’s assumed that a new service is only being operated to win a share of the revenue.

The ORCATS system helps to ensure inter-available ticketing between services, including where tickets are marked ‘any permitted route’ or where passengers are making journeys that require interchanges.

ORCATS doesn’t cover Advance tickets, which are only valid with one train operator. That means an open access operator can sell most of its seats on Advance tickets and keep all the money it makes from selling those tickets, while still getting a share of revenue regardless of whether there are any seats available for passengers with an ‘any operator’ ticket.

Currently, franchised operators are required by law to provide a certain level of unbooked seats on each train. Although manual counts of passengers and tickets can be made, it’s expensive and time-consuming, and very rarely done.

In addition, under current arrangements post-COVID, operators are no longer taking the revenue risk, so there’s little incentive to check the revenue share both now and perhaps also in the future under nationalisation.

It’s not known how many manual counts have been carried out, but it’s thought that the number is low. Ultimately, any decisions would depend on how much revenue was at risk and whether it represents value for money to do it.

ORCATS is an unbelievably complicated system which is not designed for a modern railway. Those who know the system point out that it effectively guarantees a certain level of revenue to an open access operator before it has even sold any tickets.

Labour’s Plan for Fixing the Railways document, published in April 2024, said it would simplify the ticketing system and drive innovation across the network, replacing the current multitude of platforms and a myriad of fares, discounts and ticket types, and maximising passenger growth.

It also said it would ensure that ticketing innovations such as automatic compensation, digital pay-as-you-go, and digital season ticketing are rolled out across the whole network.

Any move to a tap and go system on the railways would rely heavily on some kind of ORCATS system, so it can’t be totally phased out.

But the antiquated system does need a revamp. And, if so, will it have an impact on the revenue currently being received by open access operators now and in the future?

Whether or not you agree with the argument that abstraction and ORCATS provides a back door subsidy, for the time being at least, it’s clearly factored into business cases. And it could be argued that it enhances the viability of a proposed service.

But Ian Yeowart maintains that ORCATS is ‘yesterday’s news’. He says: “The vast majority of tickets sold now are operator-specific and train-specific. So that operator gets 100% of that revenue and doesn’t share it with anybody. ORCATS sharing just isn’t happening any longer.

“When we started all this 25 years ago, there were no such things as operator-specific Advance purchase tickets, and that is virtually the entire ticket sales now. I know very few people, unless you’re on a local service and local services are different, who turn up on the train and just buy an open return.”

What Yeowart says is certainly the case in France, where open access thrives. There, different operators sell only their own tickets, and keep all of the revenue.

From Lyon to Paris, TGV trains (operated by SNCF), regular SNCF services and Italian company Trenitalia all compete on the same route. If you buy a ticket with Trenitalia, you won’t be able to use any of the other services. There’s no inter-available ticketing, but on a specific route such as this is it needed?

On the subject of open access, Labour’s Fixing the Railways document also stated that the ORR will continue to make approval decisions on open access applications on the basis of an updated framework and guidance issued by the Secretary of State.

The DfT appears to confirm this stance, suggesting that where open access adds value and capacity to the network, operators will be able to continue to compete to improve the offer to passengers. It has promised to set out details in due course.

Yeowart says: “It is still a challenge to get any approval because the regulator remains independent - and will remain independent (we understand), going forward. So, we’re still going to have all these hurdles to overcome.”

But following the Prime Minister’s backing of the FirstGroup train deal with Hitachi, and the possibility of a further big order should First win more open access rights, it seems as if the scope for major changes will be limited - particularly if future similar deals are to be struck.

Despite the rail reforms that are coming over the horizon, open access and private train operations, in a cash-strapped renationalised railway, appear to be not only here to stay, but positively encouraged.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.