The following article is featured in RailReview - the new must-read business journal, website and monthly digest for the rail industry https://www.railreview.com

The following article is featured in RailReview - the new must-read business journal, website and monthly digest for the rail industry https://www.railreview.com

A confluence of unique things. Each is small, but they’re seismic together.

That’s Malcolm Brown’s view of rolling stock leasing. His view matters because he’s chief executive of Angel Trains, one of the big three rolling stock leasing companies created at privatisation 20 years ago to take over British Rail’s fleet.

He’s also the owner of the trains that have triggered such an intense interest in this area - the Class 707 electric multiple units being delivered to South West Trains. They’re being delivered but they have no future there, because new operator First MTR, which takes over this summer, has promised a new fleet to replace them.

Brand new trains with no apparent future. A money earner shunted into sidings. Why?

Two reasons. Trains are cheaper today than they were even a couple of years ago. Today an EMU vehicle is around £1.2 million. They used to be £1.5m. Money is as cheap today as it’s been for many years. Put together, it’s cheaper for train operators to lease a brand new train than even one ordered a couple of years ago.

Brown ordered 150 Class 707 vehicles in 2014-15. “They cost significantly more than they would cost today,” he tells RailReview. When First MTR and Stagecoach were bidding for South West last year he reduced the lease price, but it wasn’t enough to secure his new investment a home.

Other factors were at play. The Class 707s are now one of five fleets on SWT’s Windsor routes - the others are Classes 450, 455, 456, 458. All will be replaced by a single type that should be cheaper to run and maintain - not least because they will all be the same, which drives efficiencies in spares holdings and in training for crew and maintenance staff.

The ‘450s’ are protected by government usage guarantees, and will be switched to other routes on which they already run. The other three types have recently been part of an investment project to run ten-car trains.

That project featured extensive and expensive work on the ‘458s’ to increase them from four-car units to five-cars, using Class 460 coaches made redundant from Gatwick Express. Meanwhile, the ‘455s’ had new traction equipment fitted and their DC motors replaced by modern, more efficient AC ones.

Porterbrook paid for this work on the expectation that the units would have continued use with SWT (based in Derby, Porterbrook is another of the three ROSCOs - the third is Eversholt Rail). But the decision by First and MTR to introduce a brand new, uniform fleet of trains (they have not yet revealed the builder or financier) gives Porterbrook Commercial Director Olivier Andre a problem: “We took a view that they would stay on lease until the 2030s, and that was the basis for pricing them. They will be displaced in 2020 and there is no certain home for them.”

Andre and Brown face the same challenge… what to do with their displaced fleets? They’re all third-rail fleets, only suitable at the moment for lines south of London - SWT, Southern and Southeastern. The latter franchise is soon to go to competition to find a new operator. How do they set their price? They need it to be high enough to pay back their investment, but low enough for their stock to be competitive against other owners.

Even then, the bidders might find cheaper funding from someone else, and submit bids that include a large new fleet ordered to replace some or all of today’s Southeastern trains.

A CROWDED MARKET

That’s the situation at Greater Anglia. Abellio’s winning bid will bring 1,043 new vehicles to replace every train now running on the franchise… every single one! The bulk of today’s GA fleet consists of overhead line AC EMUs. Brown’s ‘707s’ are DC EMUs, but could be fitted with pantographs to make them able to work under AC overhead lines. However, he would be putting them into a crowded market that faces a glut of stock. Andre reckons that in theory he could do the same with his ‘458s’, but they’re an older design and it might not be easy (or cheap).

For his ‘455s’, Andre is toying with equipping them with diesel engines to make them a diesel electric multiple unit. This could be a canny move. It builds on the research and design work that’s gone into adding diesel engines to his Class 319 dual-voltage EMU fleet, and takes advantage of a shortage of diesel multiple units (of which more later).

In bringing new trains to Greater Anglia, Abellio is ditching EMUs that date from the 1980s (to no one’s great sorrow), but also trains dating from the 2000s and from this decade. One financier, speaking to RailReview anonymously, described that 2010s fleet (Class 379s) as the canary in the mine that alerted his community to the looming problem with rolling stock leasing. He added that if the ‘379s’ had been the canary, the ‘707s’ were the mine explosion.

Money was the trigger. It’s very hard to find a decent return, as any saver looking at paltry interest rates knows. Bigger investors, such as pension funds, need to find somewhere to earn more money - not least because we’re all living longer and needing pensions for longer. They have often invested in infrastructure because it gives long-term, consistent returns.

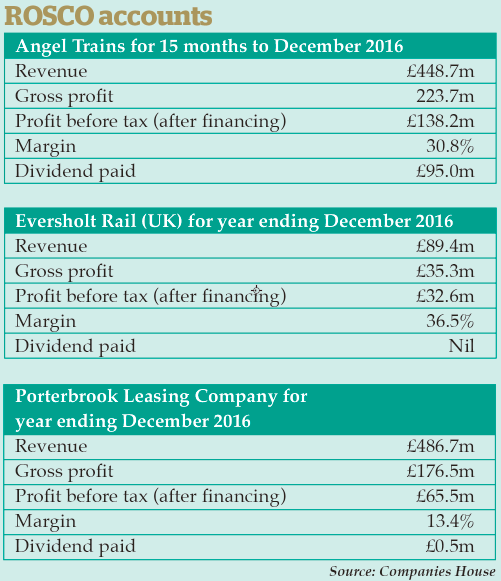

In short, there’s a lot of money looking for an investment home. This money turned its attention to rolling stock. It saw decent returns - the ROSCOs make good money (see panel, page 68) - and a railway that was growing. But, according to the anonymous financier, it overlooked a key point - rolling stock can be discarded in a way that infrastructure usually isn’t.

He explains: “When you buy a fleet, you don’t buy it for 100%, you buy it for 100% plus your interest that’s accrued for two or three years, because you don’t have any income coming in. You have fees with the operator involved in managing the manufacture, or there’s a separate team. There may be separate fees from the operator if it’s involved with getting licences.

“So you get this profile of: here you make a 40% payment and another 40% payment and a 20% payment, and on top of that you have interest accruing, and so you get to about 107% of your asset just as you start coming into service. And then your lease may be three years, it may be four years. Now, at that four-year point you may not have got that 7% down to 100, so you amortise it - and in the early days, people were amortising over 30 years. And then you’d say that at seven years, the fleet’s going to come back and then it’s going to go out again for another seven years, and you look at it over that point of time.”

He continues: “So I just think in operating lease terms. You have a high residual value at year three, year five and year seven. You’re not even going into your 90s yet, so you have to think about the risks involved over the full life to do that.

“Infrastructure is very different. HS1 - that’s infrastructure, that’s going to be there for God knows how many years. It’s long-term, there’s no sort of changes happening to it unless people suddenly decide they’re not going to take the train anymore. It’s a piece of infrastructure that provides them with an annuity over the 30-year period. That’s how they look at it. With operating leases, the asset can come back. What you’re seeing today is your asset coming back.

“You’ve had an infrastructure mindset that never came into our industry at the beginning. We were just a sort of backwater, weirdos in the bank, a bunch of rail guys who are a bit strange but seem to do alright. Where you’ve seen that flip now is where you have advisors, consultants and (most probably) money burning a hole in a pocket because of liquidity and QE , you’ve seen infrastructure funds suddenly going ‘let’s have a look at this market place’. They’ve seen high utilisation over a period of time and gone ‘well, this is just a 30-year asset which is going to be there for 30 years and that’s fine’.”

In essence, he’s arguing that investors have come into the rolling stock market with an infrastructure attitude, and that the return of new ‘707s’ and almost-new ‘379s’ has been a sharp reminder that rolling stock is a much more uncertain market.

Andre comments: “I think things like the ‘707’ making its way into the mainstream media, like the BBC, it will probably make investors think twice about the risks attached to trains. Some people financing new trains have a very slick pitch saying that it’s a risk-free asset because the railway is growing all the time and will need more stock - what’s not to like? It will be great forever. But it’s not exactly that.”

ROSCOs have been talking about ‘residual risk’ ever since privatisation, but no one really believed them because there was no stock sitting in sidings, off-lease. Stock was replaced but the older trains headed for scrap, not store. Many were former BR trains that were long past their sell-by date. Others were displaced by government deciding to ban slam-door Mk 1 trains on safety grounds. This led to a massive fleet replacement programme taking place on SWT, Southern and Southeastern.

RISKS WITH NEW TRAINS

Yet there are risks with bringing new trains into service. There may be problems building them. They may not work properly. Recent deliveries from the likes of Siemens and Bombardier have been reliable (they worked ‘out of the box’), but older hands remember the problems Alstom had with its Classes 175 and 180 DMUs in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

New stock is now on order from CAF and Stadler, both of which have very little experience of the UK railway. That’s not to say their trains will have problems, but there’s no certainty. And that translates into risk.

There’s a risk of problems developing part way through a fleet’s life, as Heathrow Express found recently with cracking in its Class 332s. Andre uses this example to push the advantages of a ROSCO, with its engineers as well as its finance experts.

Then there’s the risk of a fleet not finding a new use when a franchise ends and the new operator has other ideas. Your fleet might not have a life of 30 years, it might just have a life of four sets of seven years. You cannot be sure, and so that’s a risk.

One of the new players in the rolling stock market is Rock Rail. It has netted deals for 150 vehicles to replace Moorgate Class 313s (worth £200m) and 378 inter-city EMU and regional bi-mode vehicles for Greater Anglia (£600m). Rock found funding from several sources, including SL Capital (a long-term infrastructure fund) and pension funds such as Greater Manchester and London.

RailReview approached Rock for an interview in April. When its reply came in mid-May, it was to say that it had no time until July, long after this issue of RailReview went to press.

Despite the concerns expressed by RailReview’s anonymous financial man about risks being ignored by new entrants, Rock’s team has plenty of experience. Founder Mark Swindell worked with Agility Trains on IEP financing, and advised Connex on its procurement and the introduction of Bombardier EMUs to replace slam-door stock. Rock’s team also includes Roger McDonald, whose career includes time as senior vice president of Alstom and managing director of Thames Trains. More recently he worked with DfT on the introduction of new trains to Thameslink.

With this experience, Rock should be very well aware of the risks involved with financing and leasing trains.

Rock’s appearance in the market place - together with Macquarie and its Class 379s, Beacon Rail financing TransPennine Express’ new stock, and Lombard with Caledonian Sleeper’s new coaches - might be a sign that the market is finally becoming a market (a decade ago a Competition Commission inquiry was looming, such was the Government’s dissatisfaction with train leasing).

Together they provide competition for the established ROSCOs. And everyone RailReview spoke to for this article agreed the market was a good idea. There was general agreement that with markets come winners and losers. No one wants to be the loser, but if there’s a true market then it’s inevitable that someone will.

RailReview’s financier comments on Rock founder Mark Swindell’s crowded diary: “He’s a very busy man because he’s done just under £2 billion in business without a cent of income, because he’s building a portfolio and he’s building in the long-term. And it’s backed with pension money, and so he’s really shaken it up. You’ll only find out over time whether that move has been a good move in terms of the pension fund or not. What are the assumptions? That you can increase rents? Because if you can, this market is showing you that you can’t.”

Greater Anglia’s complete fleet replacement and South Western’s substantial replacement may simply reflect a point in time where trains and money are cheap. The key questions surround whether either can become cheaper or more capable.

One customer doubts they will. RailReview spoke to a senior man within a TOC owning group. Speaking anonymously, he reckoned that trains available to order now were lighter, more energy-efficient and easier to maintain than they’d ever been. “The market opportunity for new builds is very attractive - trains are cheaper, cleaner, their doors are faster and they have more space.” He muses: “Will vehicles get another eight tonnes lighter?”

His point is that there has been a step-change in the quality and capability of trains over the past couple of years. “Will the next generation be that much cheaper?” he asks, before adding: “I can’t see finance getting that much cheaper.” In a telling aside, he adds that it was in the leasing companies’ interests to make people worry about rolling stock leasing.

Government sits behind many of the improvements the TOC owner mentioned. It placed large orders for inter-city and commuter trains that encouraged manufacturers such as Hitachi to develop its electro-diesel bi-mode IEP, which (as AT300) has won separate orders as well as the Government’s. Likewise, Bombardier and Siemens developed the next generation of suburban EMUs for Crossrail and Thameslink with their Aventra and Desiro City types respectively.

Government’s action has been expensive, not least with a 27½-year guarantee that Hitachi’s IEP fleets hold. But it has helped bring new money to the market and created stiff competition between manufacturers, the TOC owner says.

The next few franchises may also trigger substantial fleet replacements, but the real test of whether the market has dramatically cut the lifespan of trains will come when Greater Anglia next comes to renewal in 2024. If its new fleet were to be displaced, then there will be shocks all round. But if you take the view of RailReview’s man at the TOC owning group, there’s not likely to be another step-change in cost, quality or finance that will undercut them - unless GA’s new fleet owners, Rock and Angel, decide to push lease rents too high.

HIGHER CHARGES

Rents will rise if the market decides that the lives of trains are shorter. If a fleet were to be amortised over 20 years rather than 30 years, it will need to attract higher charges in order to pay its way and earn a return, unless ROSCOs decide to cut their margins in the face of competition. But pitch rents too high and you increase the chances that your fleet will have a short life.

RailReview’s finance man puts it simply: “Try to persuade a credit committee or a board of directors that you’ve got a 90% residual value that you have to amortise over its whole life, and you’ve come a cropper at the very first hurdle, meaning that it hasn’t even got on lease. People will sit there and go ‘bloody hell’. You’ve woken up a sleeping horde.”

One forthcoming franchise needs at least one new fleet. East Midlands Trains should change in summer 2018, with incumbent Stagecoach competing with First/Trenitalia and Arriva. The winner will need to decide what to do with the franchise’s HSTs - they have not been modified to comply with Persons of Reduced Mobility (PRM) regulations, and so must be withdrawn by 2020. But the 18 months between franchise award and PRM deadline is unlikely to be long enough to order and commission a new fleet, so the HSTs will need to be modified.

As Olivier Andre at Porterbrook explains: “If you want to make them PRM-compliant, you need to spend quite a lot of money per carriage to change the doors to have power-doors put on. You’re not going to spend that sort of money if the trains are only going to be used for one year after 2020.

“In the current market conditions, are we willing to take the risk and invest a lot of money, and take the position that the trains will still be in use in 2025 to reduce the leasing costs? Probably not, so all we do is price it over a much shorter period of time, so the costs will be quite high for the TOC. Or the alternative is that the Department gives us a guarantee that our trains will be used for longer.”

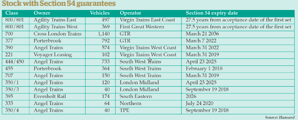

These guarantees are generally known as ‘section 54s’, after the part of the Railway Act 1993 that provides for the Secretary of State to direct train operators to use particular stock (see panel opposite). They reduce the re-leasing risk, and so can provide for lower lease prices at the risk of constraining the market.

If a complex fleet project (such as SWT’s Class 455, 456 and 458 one) comes round again, or compulsory modifications are mandated by Government, then it’s more likely that funders will ask the DfT for section 54 protection.

RailReview’s financing man comments: “Someone will now say ‘well, if you want me to do this, I want a section 54 because I’m just going to get burnt’. So the DfT, to me, are just brewing up a problem. Aggressive franchising bids and aggressive assumptions for funding for long-term assets equals you’re going to have a difficult time.”

Other ROSCOs implemented PRM modifications earlier. Eversholt Rail speculatively modified its Class 315s, even though it knew they would be displaced in London by new Crossrail Class 345s before the PRM deadline.

Eversholt’s Relationship Development Manager Tim Burleigh explains that it did this with an eye on the electrification of the Valley Lines in South Wales. Despite dating from the early 1980s, the ‘315s’ could have provided a cost-effective fleet, helping the overall business case even in the face of cheap trains straight from the factory.

Except that there are no wires being erected in the Valleys anytime soon. Furthermore, DfT’s plans to wire the Midland Main Line and trans-Pennine route have foundered in the mire of Network Rail’s struggling Great Western wiring project.

Will Britain see more electrification? “No,” according to Brown. “Not in my opinion, although no one’s broken cover to say so.”

Eversholt initiated its Renatus rebuild of Class 321s to market them to Greater Anglia bidders. Thirty of the fleet of 110 will be upgraded with air-conditioning, modern traction systems, AC motors and other improvements. The company’s fall-back position for the fleet would have been the lines DfT and Network Rail planned to electrify. Now it’s faced with the prospect of displacement from Greater Anglia and no future home, despite the improvement project.

Instead of cascades of EMUs bringing cost-effective trains to newly electrified lines, East Midlands bidders face the prospect of having to order new diesel trains or bi-mode trains. A new operator should be in place in Wales from autumn 2018, and will be looking for diesels to replace Pacers from 2020. But the market is very tight.

According to Andre: “You don’t really have a choice at the moment. CAF offers a product, Stadler can offer one, but it’s done it in bi-modes at the moment and it’s quite expensive. I think in time, people will have to buy some more - probably bi-modes rather than pure DMUs, because from a financing house point of view it doesn’t make sense to buy something that’s purely diesel. The orders are always quite small, so it’s difficult to get good pricing.”

Reading between the lines, expect such diesels to be expensive, because orders will be small and there’s not much competition. Some DMUs are being displaced, which should ease the market. TPE is casting aside part of its Class 185 fleet, and there should be Class 170s looking for new homes.

How might a DMU shortage affect the market? Or the reverberations from EMU changes?

According to RailReview’s financier: “What will most probably happen is that they will say ‘hold on, I’m losing something over here, I’m going to get you back next time somewhere else’. ‘So you say you want ten diesels, I’ve got ten diesels - the price may have been five, it’s now ten’. ‘Why is it ten? That’s really expensive!’ ‘Well, it’s because that’s now the market price, because our assumption under this lease is that they’re not going to last more than five years because of replacement risk going on’.”

The biggest longer-term factor will be the balance between diesel and electric stock. This depends on what DfT decides to do with electrification. For the past few years, the messages from DfT have pushed electrification as the future. So will there be more wires?

No, says Brown. Yes, says the TOC owner. He admits the DfT wouldn’t want to do more and that NR doesn’t want to do more, but argues that environmental concerns will insist on it. “People’s attitudes to air pollution have changed over the last few years,” he says.

In the motoring world, the Government has turned sharply away from diesels. Secretary of State for Transport Chris Grayling recently warned motorists to think long and hard before buying a diesel car. If that resonates with the public, they will wonder why he’s pushing rail down the diesel road by ditching electrification.

Noting that the Voyager fleet of diesel-electric multiple units is looking for a new owner, Brown said he’d looked at it but didn’t want to buy diesels. But he doesn’t want to buy electric either, because of the uncertainty over wiring. Yet with trains cheaper than ever, and with finance also cheap, now is surely the time to invest.

“I could buy now and wait for the market,” Brown muses. Then he recalls the warning that comes with every TV ad for financial services - the value of your investment may go up or down.

Would you buy stock speculatively, RailReview asks Andre at Porterbrook?

“We will see, again… at the moment, you’d have to be very brave,” he replies.

Andre explains Porterbrook’s last speculative build: “We did a speculative build in 2015 when we bought some ‘387s’ from Bombardier. That gave me sleepless nights because that was really, really speculative - there was no customer. It ended up well because they ended up at Great Western and the size went from 20 to 43, so that was all good.”

Some of those ‘387s’ are now working Great Northern services, and look set to displace Class 365s owned by Eversholt. Overall, there could be very little increase in overall fleet sizes as a result of all these new trains. Yet passengers complain about overcrowding. And there’s a prospect of passengers on busy trains glimpsing others stored in sidings (assuming there’s enough siding space). At face value, this will look crazy, but there’s little track capacity to use surplus stock. And capacity sits firmly with DfT and its subsidiary, Network Rail, rather than with the competitive market for rolling stock.

With NR pleading lack of funds, you’d not want to bet on major increases in capacity on today’s network (future capacity increases will come from projects such as HS2 in the middle of the next decade, together with a new fleet). But here’s a disconnect between network and fleet spending.

“raiding the sweet jar”

RailReview’s finance man notes: “What I don’t understand in this market place is you see Network Rail, which gets £35bn over a five-year period to spend on its infrastructure. It’s overspent it, and people have been told there’s no more for rail - it’s over! But for trains and franchising, under a franchising system - hey, let’s go wild!

“You have 6,000 vehicles being delivered over the next 44 months. That’s a tremendous amount, but I think people are raiding the sweet jar and this will come home to roost. People will want to see a stable market, but I don’t think it’s stable and I don’t think the DfT thinks it’s stable.”

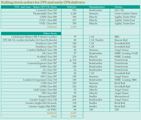

With 13,000 vehicles in today’s UK rail passenger fleet, that 6,000 represents almost half the fleet. Yet Brown reckons the overall increase in size will only be around 2,000 - after spending billions of pounds, the fleet will only increase to 15,000.

That implies around 4,000 vehicles going for scrap. Some should certainly go - they’re old and past their prime. But others still have life, and at any other time would be refurbished, upgraded and given a new lease of life.

Such a flood of new trains looks set to kill the refurbishment market, which worries those RailReview interviewed for this article. They are concerned at the loss of skills and jobs from the market, and the potential loss of the players themselves from Britain - not least because they are also suppliers of new equipment to train builders.

Furthermore, several emphasise that refurbishment can be cheaper in environmental terms than building new, because you generally keep the major components of a train, the body and bogies.

“The DfT is putting more emphasis on sustainability. The carbon impact of refurbishing is quite significantly lower than new-build,” says Eversholt’s Burleigh.

Andre comments: “It is a lot more CO2 intensive to build new than to maintain something that exists. In operation, the new train will use less energy and be lighter, but the big expense in CO2 is when you actually build the train and make the extrusions. That’s not been taken into account by anyone.”

On jobs and skills, Andre continues: “DfT is part of a government which has published an industrial strategy. Having lots and lots of new trains is great from the DfT view of keeping passengers happy, but it has a broader impact on the industrial strategy.

“In times of Brexit, they need to have a very clear industrial strategy that is sustainable in the long-term. Having UK train manufacturing places churning out lots and lots of trains, but then having a cliff because of where do they go next, is not great to sustain jobs, skills and everything else.”

He adds: “If you take people like Wabtec and Knorr Bremse Rail Services, having lots and lots of new trains obviously kills their business pretty drastically, because it’s not viable financially to refurbish trains. But there are jobs attached to these companies - quite a large number of jobs, thousands of jobs.

“These companies also happen to be suppliers of OEM equipment on new trains (Knorr Bremse supplies brakes and doors, for example). But they are not made in the UK at the moment, so if we think that we need to increase the local content of trains then the big bits - the brakes and the doors - need to be made in the UK.

“If the companies that would potentially make them in the UK, like Wabtec and Knorr Bremse, have been killed off because their current market of refurbishment has been killed, then they will leave the UK.

“And there is no way to build the local content if these manufacturers are not here. In a way, keeping them going with the minimum of activity is actually, in the medium and long-term, quite good, because then they will invest in the UK to do new build at the right time and with the right level of local content.”

Recent refurbishments have concentrated on modernising trains introduced by BR. From a passenger’s perspective, the major change has been to fit air-conditioning. But when the trains ordered in the 20 years since privatisation need refurbishment, this will not include air-conditioning because it was fitted from new. Instead they might concentrate on improving computer hardware and software.

Doubtless needed, this sort of improvement will score less well in terms of quality scores in franchises, whereas a brand new train always comes with a quality premium - or at least the perception of it. Having seen new trains arrive elsewhere, how will passengers and stakeholders react when their franchise only receives refurbished carriages?

There’s another aspect to the cost of trains… and that’s maintaining them. Traditionally, railway companies maintained their own trains. Today, it’s common for manufacturers to maintain the stock they built - either directly or under contract from train operators.

Hitachi will be responsible for maintaining the IEPs it is building for East Coast and Great Western services. Siemens maintains the Class 185s that TransPennine Express uses at purpose-built depots in Manchester and York. It has done this since they were introduced a decade ago, so no train operator has any experience of keeping them in traffic.

This poses questions about where the trains will go when TPE hands back part of the fleet to its owner, Eversholt Rail. Can the railway as a whole afford another dedicated depot being built? Or does the new operator do a deal whereby it maintains the trains with Siemens providing technical support and spares?

RailReview’s finance expert has met the maintenance problem before. He explains: “My other big problem was maintenance pricing and the ability of the manufacturer to understand the whole-life cost of his asset.

“Every time we came round to doing a maintenance contract, they put the maintenance up. And you had no choice because you’re the owner, who else is going to do it, and you prefer the OEM because he built it and he should know, and all that good stuff. We’ve always found that if someone’s offering cheap maintenance they may be doing it to begin with, and the price goes up later. This is what you may see with some of the cheaper deals in the market place, and then someone says in 2023 that the rent’s going up and the maintenance is going up.”

So where does that leave rolling stock leasing? It’s no longer the preserve of the big three ROSCOs. New money has come into the market. But that money can leave just as easily, as pension funds switch investments to chase the best return almost as domestic consumers can switch utility companies. They will look to sell for a profit, but there remains a chance that someone will catch a cold if DfT chases short-term headlines over long-term costs.

CERTAINTY INTO ELECTRIFICATION

The DfT needs to inject certainty into electrification plans, by either committing to expansion or ruling it out. It cannot continue to hedge its bets without paying a price in terms of higher charges for rolling stock (which translate into lower premium payments or higher subsidies for franchises).

It will take a few more years before the railway knows whether fleet lives have been cut. Early disposal of Class 707s from South Western catches the headlines, but it looks more like an extreme than a new norm. That’s not to say that future franchises will not replace large parts of their inherited fleets, but it’s hard to see money or trains becoming markedly cheaper than they are today.

The market is approaching a turning point where new orders become more scarce as the pricing effect of cutting the lives of fleets appears in the bottom line of franchise bid projections. Most commentators expect passenger numbers to continue rising, although they argue about the rates of growth. This means that more stock will be needed. That stock will continue to provide a return for investors.

This article can be found in RailReview Q2 2017. If you would like to find out more or subscribe please go to https://www.railreview.com/subscribe

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.