Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature here.

You wouldn’t expect a possession overrun to result in a blue light emergency response. But that’s precisely what happened at Clapham Junction in the early days of the Network Rail-South West Trains ‘Alliance’.

No track workers were injured. But four ambulances were called for passengers aboard delayed and disrupted trains during the Monday morning overrun near Twickenham. And, of course, more delays accrued from the time it took paramedics to reach the stricken passengers and treat them.

Alliance Managing Director Tim Shoveller recounts this tale to show how incidents on one part of a railway can affect another.

“When Network Rail talks about a possession overrun it would think about the safety of the people on the site, quite rightly, not wanting them to put them under pressure to get the possession done quickly. I completely applaud that.

“But we also have to understand that when a possession overruns the consequence is not just about the workforce, the consequence is also about the passengers who collapse because their trains are so overcrowded.”

Shoveller had started this story by talking about the costs involved, before developing his argument to show how his railway now reacts differently because the track and train operator are joined together.

A Monday morning overrun is clearly visible in the takings from ticket machines and booking offices. In this case, they dropped £300,000, he recalls.

“We were able to see the consequence of that possession overrun as a railway,” he tells RailReview.

“And what that meant was, yep, there was the Schedule 8 cost to the Route (which is shared with SWT), and there was a loss in revenue that was equivalent to £300,000 because people didn’t - couldn’t - travel. The two to three-hour overrun took out the Monday morning peak. So Schedule 8, which was equivalent to £300,000 funnily enough, and £300,000 from people - it’s the equivalent of £600,000, as well as huge disruption.”

He continues: “If you join the whole thing together you get a different view of safety. The point is that it’s not one thing or another. You take a different view on what the costs are. Those types of event are unaffordable. So at a time when McNulty was perhaps saying there was too much contingency, perhaps we should say: ‘no, no, no, no. On this railway - perhaps not a typical railway in terms of volumes or revenue - it’s not right’.

“I’d do anything to avoid a £600,000 possession overrun. And I’d do an awful lot to avoid taking four passengers to hospital because the train was so overcrowded. And of course, when a passenger faints on a train, it delays the service. So at the very time when the railway is already broken, you create a yet greater dislocation of service.”

A crowded network

When the Alliance was launched in 2012, it was very clear about what it wanted to achieve. According to its press release: “It is aiming to cut delays for passengers, provide better customer service, deliver more effective management of disruption, and improve the efficiency of the railway through more collaborative working and better decision-making.”

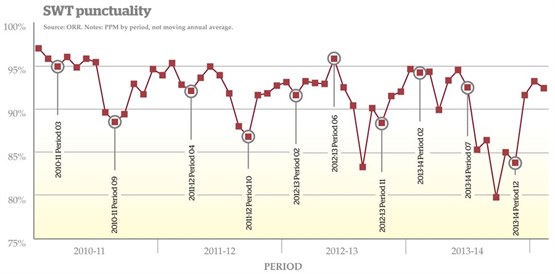

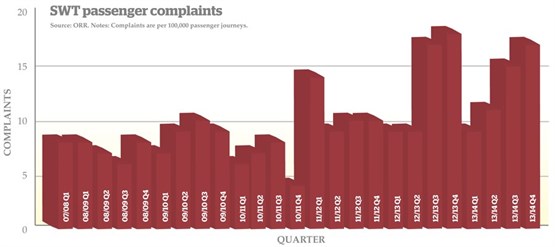

On those measures, it’s failed. Performance has dipped, passenger complaints for South West Trains have risen, and National Passenger Survey satisfaction scores have fallen. But is this the whole story?

Shoveller does not duck the statistics, but says: “Is the Alliance working? Absolutely, yes! Define what working means. Have we saved hundreds of millions of pounds? Is train performance better than it’s ever been? No. Did we ever think that was likely? Er, no. But nevertheless, that’s the common expectation.”

Reminded of the words of the press release, he continues: “Is it better than it would have been? Absolutely! No one disagrees with that. Is it better than it could have been? Bloody right! How could it not have been? There’s a counter-factual argument to say ‘why would it be worse then?’

“When we talk about all the initiatives that have been delivered, and doing a lot of what I would call the basics - getting a lot of the basics right, which to a degree weren’t as in place as they should have been - how could any of those things have made performance worse? So I have absolutely no doubt, and we can prove on instance-by-instance basis that performance is better that it would have been. Absolutely no doubt.”

He sharply counters accusations of failure, and rejects suggestions that his railway should be divided. He argues: “The performance deterioration started 18 months before the Alliance started. If you take out last winter (and it’s crazy to include last winter because it was the worst winter in 200 years, and there’s been nothing like it in my railway career) and replace it with an average of the last five years (and we’ve had some bad winters) you get a very different perspective on life. We have to keep a context. It was in trouble before we started.

“For the amount of effort and energy we’ve put into this, the easiest thing to do would be to say: ‘yes, you’re right, this hasn’t worked, let’s break it up’. No one has yet been able to give me any idea of why that would make it better. Everything we’ve done is about working together and solving the true root-cause of the problem. If we go back to how we used to be, then by very definition we’d have to undo many of the initiatives that we’ve now done.”

Some of the numbers implict in the Alliance are staggering. Waterloo station handles around 95 million passengers a year. The Up Fast line approaching the station handles 24 trains per hour in the peak. Passenger revenue is £1 billion a year. By 1100 each morning, SWT has run nearly 440 trains, with Waterloo handling all but a score of them.

This is a railway that’s ‘running hot’. It’s also a railway that’s almost paralysed by its own success. Shoveller accepts this description, and contends that there’s a forecast for the rest of Britain’s network: “It’s an advance warning of what’s going to happen over the rest of the country. I’ve done 23 years on the railway. I’ve done all sorts of jobs and worked in all sorts of wonderful places. I started here as a guard in Guildford. I have never ever seen anything like this in terms of the level of crowding, the level of complexity.

“The whole country is getting busier. A lot of the things we are seeing - the explosion in sub-threshold delay, the inability to renew the assets as fast as they need to be - those things will become common elsewhere.” That’s quite a prophesy.

He’s reminded that since SWT peak performance in 2011, passenger figures have grown 10%, and he exclaims: “That’s during a recession… on a railway that was already busting! I used to work 12-car trains into Waterloo as a guard. They were 12-car VEPs. Now they are 12-car Desiros. But they are still 12-cars, and they were full as 12-car VEPs. We run 24 trains per hour on the Up Fast alone in the morning peak. That’s what Thameslink will only do after £5 billion and cab signalling.”

He asks why the trains are still only as long today as they were during his time as a guard 23 years ago. Why has one of the most valuable railways in the country seen no strategic capacity interventions?

A suggestion that it’s just too difficult has Shoveller almost leaping from his chair: “Got it! Absolutely right! I love talking to you. You’re halfway there! I tell you, there’s lots of other people in the railway who ask why is that.

“Politicians will say ‘it’s because it’s a Labour government’ or ‘it’s a Tory government’. ‘It’s because it’s too difficult’. There was a scheme in CP4 to extend Platforms 1-4 at Waterloo and introduce ten-car operation on the suburban lines. It was agreed by all parties before the Alliance concluded that it was too difficult - the consequence of extending the platforms at Waterloo would have been that the trains would have required to run out of five platforms not four, because the switches and crossings that would be removed would have meant that the layout was less efficient.

“You can’t get the same reoccupation times because you then have to go further out to cross, and you lose capacity. You won’t find anything else anywhere that operates at this level of intensity with these constraints.”

At the heart of the problem lies the classic tension between track and train operators. One wants to run trains, the other wants to maintain track. They can’t be done at the same time. As Shoveller puts it: “At the start there was this mutual suspicion around the organisation. People in NR genuinely felt that they couldn’t deliver the reliability they wanted for the railway because the TOC wouldn’t give them the access they needed. And the TOC genuinely felt it couldn’t run the service it wanted to because the railway wasn’t reliable.

“When you then break it down, unfortunately it wasn’t the case that you can have a simple solution where the answer clearly is ‘do that’ and ‘ding’ - everyone’s really happy. Because, actually, both parties were right. There isn’t enough access to do the work we need to do. I can say that because I’m responsible for granting access. I have an ‘access wand’, as I describe it from time to time.

He recounts how he told his train planners that they could no longer refuse requests for access. They could either grant requests, or refer them upwards to the executive team for a decision.

However, he admits that waving his ‘access wand’ did not solve the problem. Even with access, time remained challenging. Taking electrical isolations of the third rail eats into access time, maybe cutting an hour’s working time from a four-hour possession.

Money was pushed towards this problem, but the team also looked at how they might extend their four-hour windows. The easy option might have been to take out the last train of the night, the 0105 from Waterloo. But this is often a 12-car train, and it’s often full and standing. “You can’t put that number of people on buses,” Shoveller remarks. He’s right. But the problem remains.

Even if that train didn’t run, or if it ran a diesel, the problem remains. As Shoveller notes: “What about the empty stocks that arrive into Waterloo up until about 0100 and berth in Waterloo overnight? Where do they go? Wimbledon is full. Guildford’s full. Woking’s full. Basingstoke’s full. They have to come to Waterloo. So we then understood that it wasn’t this simple thing of cancelling a few trains to solve this problem and make four hours into six hours.

“The thing is so constrained that Waterloo is actually an enormous carriage-servicing base overnight. If the empty stock can’t get in from Epsom and other locations, where do they go? Because there’s nowhere else to take them, and then there’s the train crew to get in.”

“Perhaps we haven’t built as many carriage sidings as we should have done. Perhaps we never understood that we needed carriage sidings. Was it the case that we couldn’t be bothered to build carriage sidings? No, it wasn’t. Was it the case that we didn’t understand that that was our root cause of a big problem? Yes, it was. So, we’re building lots of carriage sidings. Does that save us money now? No. Does that help the train service tonight? No. Does that mean that we can start putting the right measures in place for the future? Absolutely!”

Shoveller paints a picture of years of neglect. Perhaps not deliberate neglect, but neglect all the same. And fixing this backlog is neither easy nor quick, as Railtrack, the Strategic Rail Authority and Network Rail all subsequently discovered with the West Coast Main Line over a decade ago.

Waterloo does not have easy alternatives, as the WCML had, with trains able to divert into St Pancras instead of Euston or take different routes into Manchester. The South Western terminus might be able to take First Great Western’s HSTs diverted from Paddington, to allow Reading to be rebuilt, but we’re not going to see third-rail Class 444 Desiros resting on the blocks in Brunel’s trainshed.

Track renewals

In any discussion about the Alliance, it doesn’t take long before the subject of Waterloo starts to dominate.

It’s already been the subject of an aborted attempt to improve capacity by making Platforms 1-4 longer. And the cancellation of this project came with a sting in its tail, because it had also been planned to renew ageing track in the platforms. This was not done, but because Shoveller sits over a combined SWT-NR organisation, he was able to see the renewals work done by his maintenance teams last Christmas.

The ability to knit both sides together has brought other benefits. Alliance Operations Director Mark Steward says that 34 ballast trains ran last year with SWT drivers that would otherwise have been cancelled. SWT drivers also crew MPVs that work railhead treatment trains (RHTTs) in the autumn. Crewing MPVs means the Alliance can conduct and control light maintenance work such as recovery of scrap rail.

Other projects have gained from both sides working together for their combined financial benefit.

Shoveller lists key points work at Guildford and Southampton. At both places, it proved difficult to find sufficient access for the work. It was also difficult to find rail cranes suitable for the work, because they were in demand elsewhere. The solution that Shoveller’s team found was to close both station car parks and use them as construction bases.

He says: “We enabled work that wouldn’t previously have happened, because I could look at it from a TOC perspective and say ‘well, even though this is going to inconvenience my passengers, there’s nothing more inconvenient than having unreliable switches and crossings at places like Guildford and Southampton’.

“The Guildford example wasn’t so much for SWT passengers, it was to allow the Southern ten-car programme to be completed. So the Alliance, even though it’s very much concentrated on SWT and NR, in the Guildford example did that work and inconvenienced SWT passengers by closing the car park (and train crew, by the way, because we closed the train crew car park - that’s really radical, and has real logistical issues, where do you park at three o’clock in the morning?) for the benefit of the Southern train-lengthening programme.”

Ageing track remains a worsening problem across Shoveller’s patch, so much so that in summer 2013 the route between Overton and Salisbury (on the diesel route to Exeter) had speed restrictions placed on it to reduce the risk of buckling, even under moderate temperatures.

Shoveller takes up the story: “I didn’t see track like that when I was at West Coast or East Midlands, so why are we in this position? There’s a long and complicated view of why, but ‘we are where we are’. So, for the first time and with the fantastic support of NR’s high-output team, we brought in the High Output Renewals Train - it’s never worked on the Southern Region before, at all, ever. It wasn’t even gauge-cleared, because it can’t work on the third rail. But Overton to Whitchurch isn’t third rail, so - a hop, skip and a jump - let’s put it to work.

“With the fantastic support of that team we used it, and we broke a huge number of records both in terms of output and efficiency, because we built the train plan around the renewals train. This allowed us to do some quite radical things with the service, but what it meant was some 53km of track, that last year had heat-related speed restrictions on it, and caused delays to all of our passengers, has this year been replaced.

“There’s no way we could ever have done that with conventional methods. If you’d just taken a conventional approach between a TOC and a Route, you would never have done it. Because, as much as anything, had the case been made, I’m sure any TOC would have acted reasonably, but I’m not sure we would have understood the root-cause of the problem.

“Again, funnily enough, it comes back to car parks. One of the key things to making the machine efficient, apart from rebuilding the train plan, was in identifying what some of the key risks to the programme were. One of the key things was making sure that the people working the train had somewhere to park their cars. Without that, we’d have lost productivity and we’d have lost jobs. As it was, the thing operated perfectly. It’s out again doing ballast cleaning with that bit of track, and it is breaking all sorts of records.”

Now he leans forward across the table: “I have to tell you this is a bit of a game, because what I really want is the high-output train to do the third rail.”

This, he argues, will be a game-changer. But it’s not without challenges. Third rail sleepers are longer than normal, because they need to carry that extra rail. Then there are all the hefty cables that link sections of conductor rail. And impedance bonds. All must be removed before track renewal work and replaced afterwards.

The Alliance has spent £200,000 modifying the train to cope with longer sleepers. But it acknowledges there are still problems with all the track cables and this has still to be worked on.

“Somebody has to come in and take them off and then put them back before trains can run again. Unless we coast,that is, which I’m still working on,” says Shoveller. That’s an interesting possibility. It’s been done by Virgin with 25kV OLE, but never on the third rail.

So, the result? “In week 29 we’re going to do the first high-output track renewal with third rail as an experiment near Shawford. And once we’ve done that, later on this year we’re going to replace five miles of track in each direction at Wool, which is from the 1950s, it’s life-expired, and it has a speed restriction on it. We’re going to replace it efficiently overnight, using the machine.

“That’s a really, really big step, because once we can do that I can get to grips with some of the backlog of renewals at places like Woking and the main lines to Basingstoke, where a lot of the track was relaid in the mid-1960s for Bournemouth electrification and now needs to be done again - both track and the ballast.

“This allows us to do it in an efficient way. Because, frankly, closing the railway for 27 hours and doing a couple of hundred yards on a Sunday with JCBs is crap, isn’t it? This has to be done overnight and until we have the high-output train we can’t do it overnight. This at last gives us that opportunity.”

Reducing delays

Shoveller shifts to a different topic… delays. More precisely,

‘sub-threshold’ delays. He reckons it is the most important thing he’s learned since heading the Alliance and it’s something he feels that is important across the whole railway industry.

He ropes Finance Director Andy West into the story: “Andy’s been finance director since SWT was created, and he was here under British Rail. He desegregated Network SouthEast and has just put it back together again financially. He’s learned things about this business he didn’t know. He never knew that about 60%-70% of all our delay is never recorded because it’s sub-threshold. It’s below the contractual regime. He didn’t know that.

“For all these years people have been talking about business cases that was just about delays generated of three minutes or above. Well, the vast majority of the delay that we have never actually generates a Schedule 8 financial issue. And yet how often do you hear the regulator talking about sub-threshold delays? How often do TOCs and NR talk about sub-threshold delay?”

Shoveller reacts sharply to a suggestion that these delays might not matter: “My God! They matter more than anything else! In some respects they’re more important than the threshold delays, because if we have 7,000 minutes of sub-threshold delays, and let’s say I’ve got 2,000 minutes of recorded delay that we analyse to death and argue about whether it’s a Network Rail delay or an SWT delay, below we still have 7,000 minutes of delay that I don’t know who it belongs to!

“Those delays occur every day, so actually if we’re not managing those delays how can we expect the train service to run properly?

“The principle of sub-threshold is hugely important to the industry. It’s more important than we’ve previously understood and recognised. So that’s a learning. We didn’t know that. The people in the Route and the people in the TOC did not know that. There’s no contractual regime that applies to it. There’s no money that applies to it. It isn’t that no one cared, it’s just that it wasn’t a priority.

“So what we’ve been able to do is understand - and it’s a bigger issue for us than it is for many TOCs, and that is very clearly because of the fact that our railway is at the leading edge of overcrowding and capacity challenges.

“Inevitably the more passengers we carry, the more sub-threshold delay matters. The more we put in lifts, the more prams and buggies get on the trains, the more delays we’ll get because, actually, it’s still an effort to get from the platform onto the train. You can get to the platform OK, but if you don’t make it easier to get on the train because there are no ramps, then we haven’t thought that all the way through. We’ve thought ‘great, we want to do lifts on platforms’, but how do you get onto the train? How do you do that at a place like Clapham Junction?”

Once more in his stride, he continues: “Because we can then see the factual issues, we can then take actions and measures that we would never otherwise have been able to do. Not least because with the financials in the Alliance aligned, then it doesn’t matter who creates the delay, it costs me money. Even if there’s no Schedule 8 regime against it, it still costs me money because it’s passenger inconvenience.

“So you don’t think of it in terms of what’s the regulatory issue

or what’s the contractual issue, because actually the issue is the bloody revenue. Our revenue this year is nearly a billion pounds. If I’ve got a lot of delays, I’m not growing that revenue. Or the revenue is constrained because of the train service.

“So it matters less what the regime says or what the contracts say, because the revenue is the true indicator of success.”

Shoveller has opened a wider debate here. A large part of the railway’s regulatory regime is in place to act as a proxy for a market, or to counter a view that a railway is a monopoly supplier.

However, he argues: “The regimes are there to act as a proxy for the market where no true market exists, but we have a true market and it’s called a billion pounds worth of passengers. We can see very clearly when we do well and when we don’t. When we have a problem in the morning peak, then we don’t just think about the Schedule 8, we also think about how much money that didn’t come to our ticket offices.”

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.