Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

Ever since 1846, when Brunel’s 7ft ¼in gauge butted up to Stephenson’s 4ft 8½in railway, the need for standards has been self-evident. Indeed, the railway was among the first examples of technical standards emerging from an industrial revolution. Many would argue it accelerated such a revolution - the railway was, after all, the trigger for standard UK time (first known as Railway Time in 1840).

From such noble heritage it is therefore bizarre that today standards in rail are too often perceived as inhibitors of efficiency and innovation (see Panel 1). So what is myth; what is reality? Most importantly, what should be done in the standards arena to promote a safe and efficient railway?

In my experience, the need for standards is not questioned. However, the role of standards is sometimes confused, and so is a good place to start the debate. From here, outlining the standards landscape, exploring how standards are set (and by whom), and how standards are used (and misused!) informs the discussion. For the experienced this may be well-trodden ground, but for others, including newcomers to the industry (of which I am one of many), it is an essential precursor to debate - especially now that the ground is shifting as Europe introduces a changing landscape.

A good starting point is The Industry Standards Group report prepared in response to the Infrastructure Cost Review for Treasury, chaired by Institution of Civil Engineers past president Peter Hansford.

“A Standard can be defined as an agreed, repeatable way of doing business. It is a published document that contains a technical specification or other precise criteria designed to be used consistently as a rule, guideline or definition. Standards help to make life simpler and to increase the reliability and effectiveness of many goods and services we use.”

The report goes on to note: “Throughout Sir Roy McNulty’s recent rail industry Value for Money review, it seemed that some of the most senior people in industry and government believed that standards exist solely for the purpose of managing safety, and that standards are the sole means by which safety is managed. In practice, safety is only one of the outcomes that standards seek to deliver; and beyond standards, there are many other facets to safety management. Each type of standard exists for a purpose, which is not delivered by other types of standard.”

So, standards are not “safety standards”. Standards are part of a framework that provide a reliable and efficient railway, and allow it to operate as an integrated system (see Panel 2, page 32). The role of standards is for the design, operations and management of the railway system to ensure: compatibility at the interfaces of the railway systems; opening of the market, so that manufacturers can design with confidence; standardisation of particular solutions which reflect good practice (these tend to be generally voluntarily adopted, and are not imposed).

Ensuring that risk from all identified hazards is controlled to an acceptable level is fundamental. But this facet should not mask that at their most basic, standards are economic tools to stop solutions being reinvented in multiple and incompatible ways. If standards are thought of as managing risk, it is important that this is seen holistically - ‘risk’ does not mean safety risk alone, it means the risk of not achieving all business objectives, including cost control and service efficiency.

Many standards are prescriptive, to allow the railway to operate as a system. The hidden benefit here is the need to avoid - literally! - re-inventing the wheel.

Imagine the cost if each organisation had to assess every aspect of compatibility, the associated risk and mitigation and the evidence base to underpin its decisions. Yet standards should only be prescriptive when they need to be for a specific economic or safety reason. This is particularly true for the higher-levels standards such as TSIs, where it is the outcome that should be specified, not how this is achieved.

In the framework for a safe and efficient railway, standards sit alongside other components such as legislation, safety management systems and the competencies of people working on the railway.

The regulatory structure defines the roles and responsibilities of industry entities. Each infrastructure manager and railway undertaking is responsible for its part of the system. The law obliges them to implement necessary risk control measures, where appropriate in co-operation with each other.

So standards are an essential element of this risk control regime. The Office of Rail Regulation monitors and enforces compliance with relevant legislation and company safety management systems. It is the essential role of standards in managing risk that places standards on ORR’s agenda. (Note: RSSB has no role in monitoring compliance with standards).

Also in this legislative environment are the Common Safety Method (CSM) regulations. Application of a standard recognised code of practice is one of the three options that a proposer of change can use to illustrate that an identified risk has been controlled to an acceptable level (the other two are using similar reference systems and explicit risk estimation).

So in this legislative environment, it is critical that a standard can firstly be clearly linked to the risk it helps control. This makes it essential for the standard to be developed using a sound process and a robust evidence base. Secondly, it requires the users of the standard to have the competence to assess if the standard addresses the risk adequately, to apply the standard at the appropriate time and correctly, and to understand what additionally needs to be done to control the risk. This places increasing requirements on the competency frameworks in duty holders.

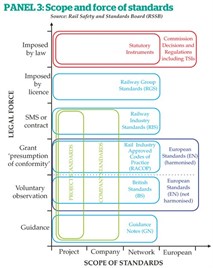

Much of the complexity in standards arises because there are many different types of standard, with differing scope and given force by different means (see Panels 3 and 4). Those with greater scope typically involve interfaces, which is where European and RSSB activity is focused. Where interfaces are not involved, standards are more usually company-specific.

When questioning any standard - whether for clarification, deviation or change - the key questions should always be what does compliance achieve and whose standard is it? These different types of standards themselves create interfaces with the opportunity for conflicting standards.

One significant trigger for change is the introduction of TSIs. From January 1 this year, these now apply across the main line network. Therefore, the work of RSSB has been to align Railway Group Standards with TSIs. This transition has enabled the opportunity to simplify the RGS regime, reducing the number of RGSs from 227 to 112.

RSSB and its members, together with the ORR and DfT, continue to work together to align the requirements of TSIs and the National Technical Rules. This reduces potential confusion and conflict between standards and reduces the potential for unnecessary double assessment of conformity.

The consequence of simplification, reducing standards numbers and a trend towards outcome (rather than prescriptive) standards has seen an increased demand for guidance. Thus Railway Industry Standards (RISs - non-mandatory requirements that can be adopted by companies as their own standard) have been introduced and are increasing in number. Where RISs are used to define good practice, this is positive. However, this should not substitute an organisation’s risk assessment competency or be used to illustrate compliance.

The other focus of the past few years has been the revision of The Rule Book. The Rule Book is unusual among Railway Group Standards in that it contains direct instructions for operational railway staff. While much of the debate around standards concentrates upon asset-based standards, the role of the Rule Book can never be underestimated in not only workforce safety (and the interface with passenger and public safety), but also the efficient operation of the railway.

Individual company standards are also part of the landscape. Inevitably, given the scale of infrastructure, Network Rail standards play a key role. Much work has been done in recent years, both in considering the standard requirements between different types of route and on overall simplification, with Business Critical Rules.

The companies in the UK rail industry have substantial influence on standards - companies set their own standards, decide which Railways Industry Standards (which are not mandatory) to adopt, and directly shape the Railway Group Standards.

For RGS and RIS, RSSB manages a committee for each asset class, comprising industry members across infrastructure managers, train and freight operating companies, ROSCOs, infrastructure contractors and the supply community. The overall strategy for these standards is set by the Industry Standards Co-ordination Committee (ISCC), again with cross-industry representation. The rail industry both defines the standards and the process by which they are set.

The role of RSSB (see Panel 6) is both as expert body and to build the consensus. Experience suggests it is the technical complexity of an issue that is the time-consuming factor, rather than the building of consensus. But consensus is essential, given the role of standards described above in managing efficiency and risk, and for no one part of the system to impose unaccepted requirements on another.

It is true that the main line industry directly shapes its standards. This is also true in Europe (if less apparent). Here, DfT (as the Member State) represents UK rail in negotiations for European standards. However, it is a role directly informed by RSSB, channelling input from members. Each TSI is reviewed by the relevant standards committee or ‘mirror’ group, and a detailed brief prepared.

More than this, RSSB - working with DfT and members - builds allies around the preferred positions. Approximately ten man-years per annum of effort in RSSB is directly attributable to Europe, including representation for work on Euronorms, typically covered by the British Standards Institute (BSI) in other sectors.

Standards may not be perfect. An individual standard is only as good as the expert judgements that have shaped it and the legislation and criteria used as the framework for these judgements. That said, considerable care has been taken in making these judgements, supported wherever possible by evidence.

It is equally true that at any given moment technology, legislative and individual company changes are in progress. Thus there will always be examples of standards that can be revised or improved. The key point is whether examples are isolated or can be generalised to a more fundamental concern.

Let’s consider these in two groups. Firstly, the nature of standards: do standards stifle innovation? Introduce delay? Increase cost? Then secondly, are the framework and processes for making judgements appropriate?

Innovation: Standards do not themselves stifle innovation. Look at the electronics sector - innovation is rapid; product lifecycles are short; new TV sets receive a signal; SD cards and USB storage are compatible. Suppliers innovate because they have to. They operate within the standards they need to (safety and electrical compatibility, for example) and innovate by identifying need and assessing the risks. Standards follow where there is either a benefit or legislation.

This is far from a perfect comparison, but is sufficient to demonstrate that it is not standards themselves that stifle innovation. In rail, the innovation barriers relate more to timeframes and payback, system interoperability, product acceptance processes, and supply chain engagement. What also stifles innovation is buyers specifying too narrowly what they want, rather than defining the problem to be solved.

When standards work at their best they promote innovation by creating a level playing field for suppliers and by specifying the outcome, not the solution. Too often customers fail to work with suppliers, neglect to introduce lean product acceptance processes, and fall back on company standards rather than risk evaluation of new products.

Innovation may be a challenge in rail. The focus and investment of recent years is making good progress, but more has still to be done. Yet standards still do not make it into the top five factors to address for accelerated innovation.

Delay: Do standards introduce delay? Not really. But poor planning does. Addressing standards at the end of a project, not the start, causes both delay and cost. Good planning addresses these factors at the start.

This assumes all project engineers are well informed about standards. If this assumption is incorrect, then RSSB may have a role to play with its members and the professional institutions in raising and sustaining the awareness.

Of course, all the foregoing refers to project delays. ‘Delay’ for the rail professional instantly brings performance to mind. Standards for degraded mode avoid the need for risk assessment, using agreed best practice to resume normal operation, thus saving time and not increasing delay.

However, the performance levels today are far below plan and expectation. Proposals from ATOC, Network Rail, the National Task Force or any quarter would be given a high priority for standard review.

Cost: Standards exist to promote both safety and efficiency. In passing, the considerable benefits of standards should not be ignored. This is not just the safety performance of the railway, but the substantial savings realised by industry in establishing a co-operative approach.

Each duty holder has obligations to assess and manage risk. That some of these obligations can be managed by reference to standards is a significant benefit - both in terms of cost and of the improved outcomes based upon shared knowledge and experience.

The challenge on cost comes from the criticisms cited in Panel 1 - allegations of over-specification for rural routes, standards lagging technology, and risk-averse specification.

In relation to scope, undoubtedly many examples will fall within infrastructure. It can be easier to apply the standard rather than do the work to justify deviation, especially with many competing priorities for the skilled engineering resources that make such judgements. Compliance with an existing standard can be the easier option.

But there are trade-offs, too. Every deviation adds to complexity - different maintenance requirements, perhaps lower interoperability for freight, different equipment requiring competencies and training.

Some costs are self-evident, but many are hidden. Undoubtedly the critique focuses on the transparent costs of specification and installation, and not always the hidden costs of whole life and whole system perspective. Duty holders manage these trade-offs for their own standards, or can seek a deviation from RGS when required.

The Industry Standards Group report noted: “Through the investigation, it quickly became clear that much of the inefficiency was not caused by British, European or other International Standards themselves, but by how these were interpreted by different clients.”

So, for this first group of issues, there is more myth than reality. Standards do not fundamentally stifle innovation, introduce delay or increase cost. In fact, in most cases the reverse is true (provided, of course, that the frameworks and processes are effectively applied).

Framework: When critiquing standards, what lies behind much of the criticism is the suggestion that the wrong judgement has been made by the committee approving the standard - whether at ERA, RSSB or company level.

At RSSB, the requirement to take a holistic approach is built into the committees’ rules for decision-making, balancing risk and economy within the parameters laid down by law. This raises the question: are standards too risk-averse for today’s railway? Do we require crashworthiness in one of Europe’s safest railways?

But some finite risks remain. It has to be for the duty holders to inform judgement based upon evidence and experience, although there is undoubtedly a role for RSSB to provide challenge and thought leadership for system thinking. Where there are potential cost savings, then the industry should not hesitate to raise them. It has to be for those who use the standards to see the opportunity.

Process: The other major critique is that standards review is too slow. With continuing technological change, it is essential that standards keep up to date at all levels.

Nowhere is this more true than new systems (ETCS, for example), but it applies to all standards. It can be faster. Inevitably there is a trade-off (set by the industry) of the frequency of change versus the speed to implement - miss a deadline, and a new standard can be delayed by three months until the next issue arises.

Using modern collaboration tools and new ideas will help. Just as importantly, refreshing the technical skills base that informs the judgements is essential. RSSB can play a key role in all these aspects. A faster review process to issue new standards will always help, but is not the core issue at the heart of standards critique.

The Industry Standards Group report made four recommendations, summarised as:

- 1 Define outcomes, not inputs: Clients should clearly define their performance and output requirements, and structure their specifications and standards to support this objective.

- 2 Enable standard assets, not asset standards: Different standards and specifications (or different interpretations of the same standard) that apply to the same asset class is uneconomic, and can act as a barrier to standardisation.

- 3 Empower industry to challenge and innovate: Clients should seize the opportunity to empower their supply chains in the early stages of projects - especially the procurement phase - by ensuring their requirements are clear, accessible and promote innovation.

- 4 Measure benefits to drive continuous improvement: Client bodies should introduce a requirement in their in-house standards development process to demonstrate clear value for money in introducing new standards.

These remain as true today. As chief executive of RSSB, I am an advocate of standards… an advocate for their role for reliability and efficiency, making a safer railway. It is all too easy to perceive a cost of standards and miss the significant benefits in safety and economy in the system. But I am not an advocate of status quo. RSSB is committed to supporting continuing improvement in the development and application of standards. Much work by RSSB (working with the industry) on alignment and simplification has already been achieved, but much more is planned.

To do this we need the full support of industry. Mention standards, and the eyes glaze over. But as standards impact directly on safety and efficiency, this is neither sustainable nor desirable.

Do standards receive the attention they require in each and every railway undertaking? Are standards on the agenda? Do you know who represents the sectors’ perspective on committees?

While standards are too often seen as an obstacle to efficiency, rather than a tool to achieve both safety and efficiency, they tend not to receive the attention they need. Companies have duties to fulfil and a role to play. Working together, we can ensure standards play their part in making a better railway.

Peer review: Ian Prosser

Director of Railway Safety, ORR

Chris gives a clear view of how the standards regime for the main line railway fits together. To a lay observer it might seem quite complex, with its various layers, but in many ways it reflects the complex world within which the main line railway in this country now operates - ranging from the influence of Europe through to the need for multiple companies to co-operate safely and efficiently to maintain system safety. European interest is focused on opening markets, improving efficiency, and harmonising safety across the sector through standardisation.

I recently heard from some quarters that standards are leading to a gold-plated railway and causing enhancement costs to rise unnecessarily. But when I look at our railway system, as I often do through cab rides and by visiting project and maintenance teams across the network, I see little evidence of what I would call gold-plating - much of our infrastructure still dates from its Victorian origins and comprises very basic component materials!

It is often the need to move to a common standard European gauge to enable interoperability that could drive costs, although this only becomes a factor at major renewal when associated costs can be minimised. More recently, there has been a welcome move to modernise standards to optimise the ‘whole-life’ infrastructure costs - unlike occasions in the past, when things were built to a minimum initial capital cost without consideration of whole-life safety, maintenance, renewal and decommissioning costs. An example is the installation of new electrification equipment that can be maintained both efficiently and in a legally compliant and safe way.

However, I believe further improvements can always be made, and I praise the work Network Rail is doing to simplify and improve its company standards through what it is calling its Business Critical Rules Programme. This will lead not only to improved efficiency, but also improved safety, particularly as it helps to ensure a clearer line of sight between the risk posed and the risk controls codified by standards.

Another myth that exists is that present standards leave little scope for applying competent engineering judgement, or do not take into account different usages of the infrastructure. This is far from the case. For example, track is categorised on the basis of its service capacity usage, and so the commensurate maintenance and inspection regimes used reflect this categorisation.

On innovation, it is interesting to reflect back on the McNulty study, which showed that the industry was perceived as having gone backwards since privatisation. I believe that “standards” do not hold back innovation - they set a reliable and efficient baseline for achieving basic legal compliance, best practice and providing scope for innovation through a positive focus on outcomes and not outputs.

From my own experience in the industry in the past 15 years, I think it has more to do with weaknesses in risk management culture. The industry, with the support of the RSSB and the Regulator, is taking bolder steps to address this via increased DfT funding and the collaboration now being facilitated by RSSB and led by the Technical Strategy Leadership Group. A number of innovative projects are up and running which I am sure are going to drive both the industry’s safety and efficiency.

Peer review: Libor Lochman

Peer review: Libor Lochman

Executive Director, Community of European Railway and Infrastructure Companies

Today’s European railway system, as a compound of inhomogeneous technical networks, has been developing on a national level for more than 170 years and is characterised by a huge variety of technical solutions. This vast complexity has led to a constant and significant cost increase when purchasing new components, or renewing or upgrading them.

So far the various standardisation initiatives, as well as a lack of co-ordination within the rail operating community, have not brought the needed breakthrough in cutting costs. The manufacturers and suppliers are increasing the variety of components within any part of the rail subsystem (such as rolling stock, infrastructure, and control command and signalling systems) being purchased by the rail operating community.

The need for a significant cost reduction is evident in order to keep the competitive capability of railway undertakings and infrastructure managers among others such as keepers and carriers. A radical cost reduction through standardisation is needed, enhanced by a closer co-operation of the rail operating community in the field of procurement.

Rail standardisation is undertaken by various players in Europe. On the one hand, mandatory standardisation (if referred in the TSI) is undertaken by The European Committee for Standardisation (CEN) and the European Committee for electro technical Standardisation (CENELEC). On the other hand, voluntary sector standardisation is elaborated and maintained by the International Union of Railways (UIC) and the Association of the European Rail Industry (UNIFE). Most partners in the sector (for example, railway undertakings, infrastructure managers and suppliers) have been developing standards/functional requirements on company level.

CEN & CENELEC concentrate most of their efforts on one major deliverable - the European Standard (EN). This document shall be given the status of national standard in all CEN member countries, who must also withdraw any conflicting national standards. Besides European Standards, CEN produces other deliverables with specific characteristics and objectives. They are the Technical Specifications (TS), Technical Reports (TR), and Guides and Workshop Agreements (CWA).

A TecRec is a UIC/UNIFE standard of which the primary field of application is the European rolling stock domain and its interfaces with other subsystems.

Pending the publication of a European standard, a TecRec serves as a common comprehensive standard, approved by UIC and UNIFE and therefore recognised as a voluntary sector standard aimed at speeding up the standardisation process - thereby improving the competitiveness of the European railway system.

UIC Rail Standards are elaborated and maintained by the UIC. Known as Leaflets, these are applied (according to their conten) by railway undertakings, infrastructure managers, industry, public works undertakings, and so on.

On company level, railway undertakings, infrastructure man-agers, manufacturers and suppliers elaborate, maintain and use their own set of functional requirements in accordance with their specific business requirements and safety management systems, and which are not covered elsewhere. Some European railway undertakings successfully work together in the EuroSpec consortium, with the aim of providing common voluntary technical specifications - as an explicit set of requirements -for rolling stock components.

On a company basis, the work will continue to draft and maintain basic functional requirements for any component of the railway system. This set of basic functional requirements is the major input for their call for tender. Preferably, the companies decide to agree more and more on a common set of functional requirements. The major focus is again on the call for tender.

As a long-term-perspective, a European Rail Standardisation Council (comprising all sector associations) should be established to recommend drafting Technical Recommendations to accelerate the standardisation at European level.

The Technical Recommendation will describe a minimum set of functional requirements on which the sector can agree. These will already be drafted in the format of the EN.

Standardisation is a mean to maximise compatibility, interoperability, safety, repeatability and quality. The approach is needed to significantly reduce costs in the railway sector. Using standards and a harmonised set of requirements in the rail operating community’s procurement process will increase the reliability of products, simplify the tender process in time and cost (as a result of fewer variations in requirements between tenders), and lead to standardised products and cost reduction due to harmonisation of train operators’ requirements.

Standards are not to be seen as an obstacle to efficiency, but more as a tool to achieve both safety and efficiency. With the community working together, having reliable and cost-efficient products available (that are both safe and easily maintainable at the same time) can be achieved.

Peer review: Scott Steedman

Peer review: Scott Steedman

Director of Standards,

British Standards Institution

Chris Fenton makes a strong case for the better use of standards to strengthen capacity for innovation in the rail sector.

BSI, as the UK National Standards Body, is responsible for supporting UK industry interests in the development and maintenance of all national, European and international standards published directly by BSI or on behalf of the European and international standards organisations.

We work in close partnership with RSSB in the development of the rail and rail-related standards produced by those organisations. Another key part of our role is to increase the awareness and understanding of standards and (in this context) how they are used to accelerate innovation across business and industry.

As a measure of scale, BSI manages around 7,000 live standards projects across the breadth of business and industry. Around 95% of our work is on European and international standards. We publish around 2,500 documents every year but we also withdraw around 1,000 standards that are no longer required by the market or which would be in conflict with new European or international standards. Maintaining a coherent set of standards for business and industry is a substantial task, but vital to underpin the competiveness of the UK economy.

Over the decades, the perception of standards as specification and even as quasi-regulation has grown, particularly in the UK. This is unfortunate, as economic studies consistently demonstrate the importance of standards in delivering innovation and productivity growth. In essence, standards are simply a consensus of ‘what good looks like’, created by experts and other stakeholders to serve a purpose. That purpose or outcome is too often overlooked, and the real value of standards as an enabler of change is lost.

At BSI, we see standards as an undervalued and underused resource to support business and industry to deliver performance improvement in a rapidly changing global marketplace. We recognise three categories of consensus standards: standards that define technical matters, related to better products; standards that describe management systems, related to better processes; and standards that set out business principles, related to business potential.

Every corporate strategy should incorporate a statement on how the organisation will use standards to address these three dimensions. It should recognise the importance of a coherent and consistent approach to the use of this knowledge in delivering its products and services in an innovative environment - with good governance, strong leadership and a motivated and well-trained workforce. Rail is a multi-disciplinary environment where businesses operate within a tough regulatory framework. Safety, quality and cost-effectiveness is uppermost in the minds of the public and government. Creating a landscape that can stimulate innovation in such an environment is particularly challenging. Voluntary standards, developed and maintained with full stakeholder engagement and open public consultation, provide one means to build trust and confidence in new approaches, whether these are addressing technical, management or behavioural challenges. To see standards simply as an obligation to satisfy safety or quality requirements is to overlook their potential as a tool for the whole community.

Over the past few years, there has been growing interest in whether the consensus building process that underpins the making of our industry standards could also be used to agree ‘what good looks like’ in the area of organisational values and principles. Human resource experts describe the gap between the commitment that people make to their organisation because they have to meet their targets, and the effort that they could put in if they were delivering their full potential, as ‘discretionary performance’. This is the difference between what an organisation is achieving and what it could achieve, if it adopted better guidance on the vital elements of good governance, leadership, motivation, innovation and risk management.

Today, BSI sees a new generation of standards emerging and unlocking the potential of business and industry to move to a new, higher level of performance. The new generation of business standards is aimed at driving performance at an enterprise level, highly relevant to the delivery of a safe, reliable rail system.

It is time to see standards for what they are, and what they were created to be – positive drivers of change.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.