Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

Sir David Higgins’ Rebalancing Britain report, presented in October, was another big milestone in the journey of HS2, following his earlier HS2 Plus report in March.

A year has passed since the former Network Rail chief executive - and mastermind of the Olympic Games construction programme - took on a role that some say had his name on it all along.

Has Higgins’ appointment changed anything fundamental about the way HS2 is perceived, or is it simply building on the way that HS2 is starting to be perceived by politicians, stakeholders and all the people needed to make it work?

Arguably, one of the most influential people at the centre of these conversations is HS2 Director of Strategic Communications Tom Kelly - another person who might have been naturally predisposed towards such a role.

To say he is simply a PR man would be an enormous underestimation of Kelly, a one-time chief spokesman for none other than former Prime Minister Tony Blair, with a background in major infrastructure projects from a similar role at Network Rail as well as for the construction of Heathrow Terminal 5.

For someone so close to the corridors of power, Kelly, a one-time journalist for both the Belfast Telegraph and the BBC, and Director of Communications at the Northern Ireland Office, cuts a friendly figure. And having supported Prime Minister Tony Blair during the Northern Ireland peace process, he’s more than used to dealing with difficult, complex negotiations involving challenging characters in pursuit of a grand aim.

The late Reverend Dr Ian Paisley once implied that Kelly made Machiavelli “look like a rank amateur”, after plans for an unprecedented PR offensive to secure a Yes vote in the referendum on the Belfast agreement back in 1998 became public. He accused Kelly of attempting to manipulate public opinion. The answer as to whether or not that is true probably lies somewhere within the National Archives, but history nevertheless points to a relatively peaceful existence in Northern Ireland in the past 15 years.

After that came the initially shaky but now well established Terminal 5, then a slicker and more confident Network Rail six months into the latest five-year plan to rebuild Britain’s railway. Bring on the next challenge… HS2.

“If I look back over the last year, I think it has been a process of explaining better from our point of view why HS2 is necessary,” he says.

“But also explaining better what the price is of not doing HS2, both in terms of capacity and connectivity. And more widely than that the North-South divide, and the balance within the British economy.

“From our point of view, I hope last year has also been about listening better to the views of those on the ground. One of the joys for me personally has been travelling up and down the country listening to the views of local representatives, whether politicians or business people, about the impact for good - and, in some cases, for not so good - of HS2, and trying to respond.

“I hope the two reports, HS2 Plus and Rebalancing Britain, reflect that.”

Nevertheless, there remains a well-organised, articulate and well-funded opposition to HS2 in some quarters. Does Kelly sense a shift from those who seek outright political opposition, and who practice outright political opposition, to those who are now simply seeking mitigation and measures put in place by HS2 to enhance its impact upon the community? MPs, local councils, campaign groups and others have all made their position clear.

“First and foremost, I don’t in any way object to people raising questions about HS2, because I think that process of challenge - and us having to respond to that challenge - has actually made the project better over the past year. And whether I like it or not, that process will continue all the way through the project, because that is the nature of big strategic projects such as this.

“Of course, there will be people for whom HS2 will have an impact on their personal lives; their daily lives. For them it is difficult to see beyond that, and I accept that.

“And we have to treat those people fairly, with respect, and respond accordingly. We cannot in any way be dismissive, either of those individuals or of the wider debate, when people say this will cost an awful lot of money, take an awful lot of commitment from the country over a prolonged period, and ask is it worth it?”

While the second and third readings of the High Speed Rail Bill, which when passed will provide the powers to build Phase 1 of HS2, were afforded a healthy majority, the politics of HS2 remain sensitive. The project is far from home and dry. What has Kelly picked up, in HS2’s dealings with politicians and key stakeholders, about the way HS2 is perceived by parliamentarians? Has Kelly sensed a shift in the past year?

Of the second reading and debate in the House of Commons, he says it “genuinely was a privilege to sit through that, because it was a proper debate, in which MPs on all sides of the house were expressing their views both as constituency MPs, but also as national representatives”.

Indeed, everyone who mattered to the project from a decision-making perspective was present in the House of Commons, either in the chamber itself or the public gallery.

“Whether they were speaking for or against HS2, I thought that was a genuine exchange of views. I thought it was a really important debate and it was important we had that debate at that stage. The result was resounding support for the project, and obviously I think that has helped to add momentum.”

Kelly clearly feels there is no room for any sense of exceptional superiority, despite that achievement. “That overall majority I do not take for granted, or will ever take for granted. We have to keep working to keep all sides of HS2 supportive, and that means we have to keep explaining to people why it’s necessary.

Real and positive change

“I think, however, the other development we’ve seen in the last year is local government leaders and local enterprise partnerships have begun to realise that HS2 can deliver real and positive change to their areas, if they think strategically about it. The key is to think strategically, because the experience of Europe is that if people think strategically about how high-speed rail can benefit their particular area, they get a real multiplier effect.”

Kelly points to localised examples where this happening: “I think you’re beginning to see that - whether it is in Birmingham, where they’ve done a lot of work thinking through how they do Kirkland Street; whether it’s in the East Midlands, where Nottingham and Derby are both collaborating in thinking through how to change; or whether it’s in South Yorkshire, where there may be disagreement between Sheffield and the region, but again people are thinking through how they can use HS2 to regenerate their area.

“Above all, I think in Leeds people are beginning to think through: how do we design the future of Leeds - not only in itself, but also as a hub for that entire area?

“So I think people have begun the process of actually thinking it through - not just HS2 as a standalone project, but HS2 as an integral part of regenerating both the local and national economies. And that’s how it should be.”

But how is HS2, as an organisation, managing the tensions? For example, the debate about whether the station in Sheffield is at Meadowhall (on the outskirts of the city) or in the city centre, particularly if another city is seen to have a more optimum station? There will inevitably be disagreements about where those stations are placed. What is Kelly’s view?

“I think the wrong thing to do would be to pretend that those tensions didn’t exist. Of course they do. And they exist for perfectly understandable and justifiable reasons. People want the best for their community, for their city, for their region. And in South Yorkshire there is undoubtedly a discussion going on between the rest of the region and Sheffield.

“We said in Rebalancing Britain that the incentive is to find balance, but on the whole that Meadowhall - as things stand at the moment - is the better option. You get exactly the same tension between a region and a particular city on the Western side between Stoke and the rest of that region. And on into North Wales, and Liverpool, and so on.”

Many of the big decisions ultimately rest with politicians, and Kelly says: “The important thing is that we are clear about the criteria by which we offer a recommendation, but equally that we’re clear that in the end it is not a decision for us, it is a decision for the Secretary of State. That is the right way it should be, because only a Secretary of State has the electoral mandate to make such an important decision that will influence the future of the particular regions and particular cities.

“And we have to be absolutely transparent about why we make certain recommendations, but that in the end it is a decision for the Secretary of State.”

Kelly returns to the theme of Higgins’ most recent report: “We have to keep putting the case, both in terms of connectivity and capacity, again and again. And we have to justify why such a strategic intervention in the life of the country is worth it.”

The development of major transport networks over the last three centuries, as pointed out in Rebalancing Britain, goes some way to making that strategic argument - with the development of HS2 particularly significant as the Victorians didn’t exactly have a central planning department for the railway.

Says Kelly: “In the 19th century the railway transformed this country. I think that you could argue in the 20th century the network of motorways transformed the country again. I think we’ve now reached the point, with London under severe transport and housing pressure and the challenges that the North and the Midlands face in terms of connectivity in particular, that we need to transform the country again.

“HS2 will not do that on its own, but it can be a catalyst to bring that kind of change. And the irony is that for all the power of social media, for all the digital connectivity that we now have, we’re slowly beginning to realise that in a knowledge economy, meetings matter.

RailReview had offered Kelly the opportunity to talk over the phone - or perhaps through some other remote means, given the possibilities that videoconferencing or Skype offer.

But Kelly replies: “I much prefer to do this face-to-face. The same is important in terms of daily meetings, because in a knowledge economy where Britain has an edge, ideas matter. Ideas flow better face-to-face. But for that to happen, it has to be easy for people to get from one place to another, to collaborate.”

Pre-committee agreements

Looking at those tensions on a more local level, newspaper reports highlighted how HS2 Ltd seeks to deal with specific issues and aspects of the route before they get to the High Speed Rail Select Committee, with engineers turning up to petitioners’ houses to prevent them going all the way to Committee Room 5.

Is this just a sensible way of dealing with things before they get elevated to that committee level? Can the legislative process be made easier by having engineers visiting people’s houses and saying: “look, we’re putting a zebra crossing here”, because it might make things a bit easier further down the line?

Kelly responds: “In the petitioning process there is a normal process of talking to people as we go through the process, and that’s what we’re doing. Now we need to be careful that we talk to people in a respectful way, that they understand the impact it is having on people’s lives.

“My view is that always you should never criticise people for objecting if something’s going to affect their lives, because if we were in the same position we would do exactly the same thing.”

However, Kelly defends the pre-committee agreements that have been struck: “Equally we need to have rational, reasonable discussions with people, and try to reach rational compromises. And that’s the process we’re going through. It’s a difficult process, it’s disruptive for people - I accept that, and we shouldn’t hide from that. But it is part of a normal process, when you’re trying to do a project like this. I don’t think a project has been invented that will not in some way affect someone’s life and that’s the way we have to deal with it.”

Kelly has had an interesting career - his own experience in politicised situations is helping to prepare HS2 Ltd to steer this through Parliament and through public scrutiny from all sorts of quarters. So how does his experience in Northern Ireland in the late 1990s onwards compare with the task he has been entrusted with in 2014?

“I joined the Homeland Office six weeks before the Good Friday agreement. On the morning of the Good Friday agreement, I was very tired because I’d been on my feet for 48 hours without any sleep. Obviously as someone who lives in Northern Ireland I was elated by the agreement, but also slightly depressed because I thought I’d done myself out of a job.”

But the following nine years were to prove that the path to peace was far from a speedy accomplishment for the politicians involved.

“Nine years later, I sat in the gallery at Stormont, the Parliament building in Belfast, alongside the IRA Army Council and leadership of the paramilitaries, watching Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness being sworn in as First and Deputy First Ministers.

“The lesson I took from that is if you’ve embarked on a strategic project - and HS2 is a strategic project - it takes time. It also takes endless discussion and conversation. Not for the sake of it, but to not only explain to people what you’re doing, but also to fine-tune the process so that you actually deliver the best result for people.

“You have to recognise that this is a marathon, not a sprint. The danger is that we think ‘oh, it’s now inevitable that HS2 will be built’. It’s not.”

Any close observers will know that there remains a considerable degree of scrutiny. The House of Commons Transport Select Committee has conducted several inquiries into the case for HS2, while the Lords’ Economic Affairs Committee has been doing the same.

“We know better today both why we’re doing it and how we’re doing it, particularly on the ‘how’ in Phase 1. But we need to keep having that conversation with the nation, with Parliament, with Whitehall, with local representatives, about both why we’re doing it and how we’re doing it.

“If the two reports have done anything, I think they have at least taken steps in that direction - but it’s steps on a very long journey, and we need to keep that going.

“We haven’t built a railway like this for 150 years. There isn’t a manual that you can take down from the top shelf telling you this is how you do it. So we’re working it out as we go along. It is inevitable that is going to involve a lot of discussion, a lot of uncertainty at the beginning as to how you’re going to do it. Our aim is to gradually add certainty to that process.”

He continues: “There wasn’t a manual as to how you did the Northern Ireland peace process. If there had been the equivalent of the Major Projects Authority, it would have given us a ‘red’ right through to the very end, because it wasn’t until the very end that we were able to know with certainty that we could deliver all the measures that were necessary to implement it.

“That doesn’t mean in any way that we should say to whoever’s asking the questions to go away and not bother us - it’s precisely those people we need to keep with us as we do it.”

That was the case with Higgins’ first report, HS2 Plus, where a lot of the content came from conversations with people - some of them supportive, some of them not.

“That’s the nature of a project like this. You have to listen as well as inspire. And we have to listen to the rail industry as well, as part of that. And beyond that, the transport industry. Because HS2 has to be seen as an integral part of an overall strategy for transport.”

That aspiration for an overall transport strategy for the UK came across strongly in the Rebalancing Britain report. Whether or not the Department for Transport had asked Higgins to start laying the building blocks of a coherent transport strategy is unclear, but the language used (and the high-level support from both Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellor George Osborne at the report’s launch in Leeds Civic Hall) seemed to suggest that HS2’s aspirations are far more than simply building a new railway between London, the Midlands and the north of England.

Does Kelly expect the rest of the railway industry, as well as other transport providers and authorities, to pick up that mantle to develop a proper transport strategy, based on what HS2 has suggested and using its framework? Grand aspirations for a Transport for London-style body have been mooted, to tie together the various threads of transport strategy in various Northern towns and cities, bringing the benefits of Oyster card smartcard ticketing and other benefits to George Osborne’s ‘powerhouse’.

“We wouldn’t be so vainglorious as to dictate to anyone else what they should or should not do,” says Kelly. “But I find it hugely encouraging that the Government has accepted the idea of a Transport for the North to mirror (in whatever way) Transport for London - to give focus to discussions about transport in the North.

“I’m delighted that the local authorities in the North have agreed with that concept. I’m delighted to see the conversations which are now taking place among the authorities in the North as a whole.”

In the past, conversations with people looking after their particular interests were much more disparate, but Kelly notes: “Now I think they’re realising the power of speaking with one voice. And in the Midlands you’re beginning to see the same sorts of coalescence. What that means is that you’re not pitting one area against another, you also don’t pit one mode of transport against another.”

In reality, this makes the connectivity improvements that you need using both rail and road easier, given the level of opposition to any new motorways. But what about Higgins’ suggestion that a new six-lane motorway across the Chilterns might be inevitable if HS2 isn’t built? Is Kelly confident, with the Government’s announcement about a new road building programme, that any new road building fits in with HS2’s plans? Do they synchronise?

“I think the important thing is that we are not in any way tribal in the way that we look at either rail or road or whatever, but that we look at it as part of an integrated whole.

Connection improvements

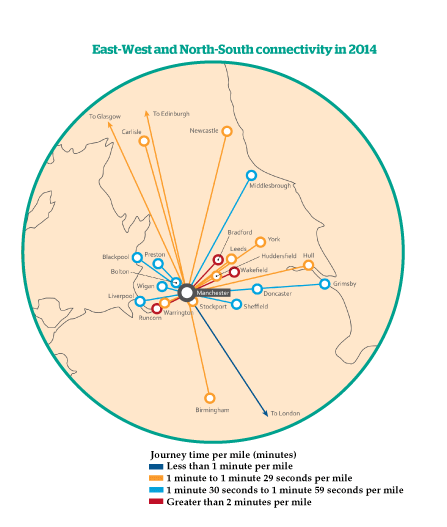

“The important step, that I hope has begun to happen last year, the first question people ask is not what, but why. Why do we need to improve connectivity, why do we need to improve capacity? And once you’ve asked yourself ‘why’, then you can begin to answer the question ‘what’.

“It is great that people are now looking at east-west links as well as north-south. But also in the One North report, it said explicitly that the multiplier effect on the economy of the North would be all the greater if HS2 and the east-west connection improvements were both done, because that would increase connectivity across the North, as well as north-south. It’s not either/or - it’s both. And it’s vital that people understand that.”

All of this new connectivity comes at a price, however, and HS2’s £50 billion budget has been much scrutinised in great detail by some of those committee and media outlets mentioned above.

The costs for Phase 2 perhaps haven’t been as tied down as those for Phase 1 - indeed, there will need to be another Hybrid Bill through Parliament to authorise the powers to build the rest of the ‘Y’ route. So how does Kelly see the budget developing over the next few years? What challenges are there ahead? A General Election looms in just a few months’ time, potentially giving rise to a change in the political weather. What sort of impact does that have on how the project is being planned?

Says Kelly: “The reality is that we live in a time where there are severe budget constraints and there will always be a tension between addressing immediate needs and addressing a strategic need, which is what HS2 is designed to address. That will not go away. We are under no illusion about that, no matter who is elected come May.

“However, I think the important thing that people understand is that doing nothing is not a cost-free option for the country either.”

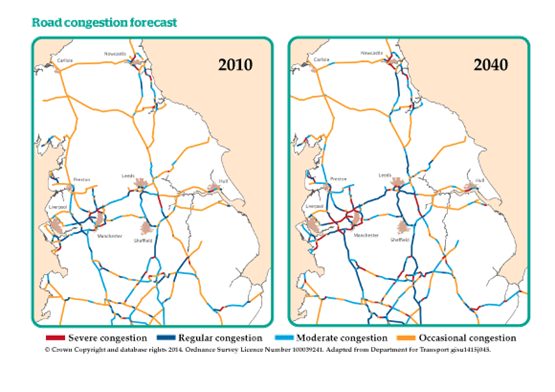

That ‘doing nothing’ means a country that would be ever more congested - with restricted opportunity to travel between London and Birmingham, or Leeds and Manchester, for example.

Phase 2

“Congestion comes at an economic price,” adds Kelly. “So too does isolation and the inability of people to make the most of their talents except by coming to London, where house prices are increasingly unaffordable for young people and where commercial property prices are now the highest in the world. That feeds into prices for domestic consumers as well. So I think people now know, if you like, the price of not doing HS2.”

Even so, that doesn’t mean HS2 is not bound to abide by the budget constraints that it has been set. “Phase 2 is three years behind Phase 1, so you wouldn’t expect it to be at the same degree of development that Phase 1 is at.”

Despite some uncertainties about future cost, there is an advantage in that the later programming of Phase 2 gives HS2 Ltd greater opportunity to learn about construction techniques that could save both cost and time (clearly, the two go hand-in-hand).

“We have to use the time,” says Kelly. “We have to learn how to do this in a way which is cost-effective and time-effective, and the practice in terms of how it’s done globally.”

The experiences of parts of mainland Europe highlight ways in which high-speed railways are built, “which we may be able to learn from”, he adds.

Although some lessons were learned from the building of High Speed 1, the learning required is almost vertiginous in its scale. After all, when Japan first introduced the Shinkansen in 1964, steam trains were still running at King’s Cross and St Pancras.

“The construction industry on the railway has done remarkable things with our railway and continues to do so. When I was at Network Rail, I looked at what they did at King’s Cross, what they did at Reading, and what they did for Scotland.

“I’m lost in admiration in the way that they can do things. But their experience is working on a Victorian railway and making the best of that. The HS2 experience is much more greenfield, therefore the way in which you approach it will inevitably be different.”

‘Business as usual’ is not, suggests Kelly, the way to deliver HS2. He explains: “We have to think our way through, how we do it. And it keeps coming back to my overall view of the project, which is that we have to take it step by step. We have to listen to the construction industry. We have to listen to the experience abroad and we have to learn those lessons.

“I hope there will be developments in the next year - but sitting here today, I wouldn’t predict it. Do I think that if you’d been sitting there this time last year, you would have been able to predict how it would have gone? Would you have been able to predict how local authorities in the North and the Midlands would buy into it like they have? No. So you take it step by step, being very clear what the end objective is.”

For any of this to work, the construction industry needs to engage with the HS2 vision. There’s a lot of pressure to deliver a value for money railway - spending a large amount of public money, but at the same time not a project that’s done on the cheap. Does the construction industry realise just how carefully HS2 needs to spend its money?

“I remember speaking to people on HS2 who interface with the industry, about a week after the Second Reading. They said they detected an immediate change in the attitude of the industry. The industry went from being not necessarily sceptical, but not quite thinking that this was an immediate priority, to suddenly thinking ‘this is going to happen and we need to get involved’.

“I think we’ve seen that level of engagement increase month by month. The two supply chain conferences held in London and Manchester in October - both were sold out.” (Kelly’s press officer Ben Ruse points out that this was a free event - but the rooms were indeed packed).

“The atmosphere at both was of both an industry that was excited and excited in the right way because they were intellectually engaged in it and I think that’s hugely encouraging.”

However, the conversation with the construction industry has “only just begun”, he says. The industry might be engaged, but as any senior figure in the railway and construction industries is only too aware, there is an immediate and pressing issue around the availability of the skilled staff that will be needed.

While the Crossrail project has been making great strides in making sure those skills exist (through initiatives such as the Tunnelling and Underground Construction Academy), and while the High Speed Rail College (located in both Birmingham and Doncaster) is due to open in 2017, is there not still a danger that the companies bidding for HS2 construction contracts won’t have the people they need?

“I think the important thing is that the conversation has begun with the industry now, about the kinds of skills that we’re going to need and about how we supply those skills,” says Kelly.

“I also think it’s vital that we recognise right at the start that to deliver HS2 we are going to have the opportunity to up-skill as a country, and to leave a permanent legacy of a skilled workforce.

“For someone who goes into this project right at the start, there is the potential to spend a large part of their career working on this project and learning skills as they go along. That is why the skills college is so important. That is why it’s so important that we develop skills right along the route, and not just in one locality. That is why it’s important that the skills college is not just based in one locality, but between Birmingham and Doncaster.

Kelly believes it is too early to say how precisely that’s going to turn out, “but I do think the industry gets it”. HS2 Ltd itself did not take the decision as to where the college would be based (this was a matter for the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills), but it was clear that politicians wanted to ensure that both cities enjoyed the benefit.

“I’m delighted to say it was not a matter that HS2 needed to have an opinion on, because in the end it was always going to be a decision that was going to be taken by politicians. It’s a bit like the Secretary of State deciding the final route for Phase 2 - that’s how it should be done in a democracy.”

We have established that the construction industry - and the wider supply chain - is increasingly behind HS2. The support of the wider railway industry is perhaps more complicated, given that it will be some time before train procurement is needed, let alone a recast of the National Rail Timetable in order to fit in with HS2 service patterns. Some of these milestones are still years ahead. So is there a message that they need to hear?

Kelly doesn’t think so: “They’ve heard and they’ve responded, and that message is more that HS2 just becomes another part of the network. The more synergy there is between HS2 and the network the better, because that allows us to maximise the output from the outset. That allows us to get the most out of the strategic advantage that HS2 will bring.

“I spent several very productive years at Network Rail. I understand the day-to-day pressures. I understand the immediate problems that they face. But I also understand that underlying many of those problems is the issue of capacity, which HS2 will help address.

“So again, it’s this tension between the strategic and the immediate. HS2 will demand a lot of commitment, time, energy, money from the industry - but the strategic prize, in my view, is worth it.”

Leaving large organisations and industries aside, it’s striking how some people who have yet to engage with the project do not get what’s in it for them.

Phase 1 might go straight through Warwickshire, but places such as Coventry and other parts of the county will not receive the direct benefits of a station, with only the big cities benefiting from a sparkling city centre terminus. But they will still gain through additional connectivity.

With this in mind, there may be more the railway industry can do, and more industry bodies can do, to illustrate those benefits early on. If it is still too early, isn’t there still a disconnect between people who can see what’s happening way off in the future, but struggle to understand the benefits now. To coin the phraseology that HS2 Ltd uses internally… ‘what’s in it for Bob and Maureen?’

Kelly responds: “I think it’s the same answer to a lot of the public, which is they will only really think about the benefits of HS2 when it is easier for them to actually see what’s in it for them.

“Whether it’s on the route, or whether it’s not quite on the route, I think as an industry we have to work to demonstrate in a practical way what the benefit is. I think that will evolve in time, and will become easier as people begin to see construction taking place, and the day when the potential of the first train comes nearer.

“If you look at, for instance, the current Leeds to Birmingham journey, which takes two hours, that will shrink to one hour. That is in an area that contains some of this country’s most advanced, most high-tech manufacturing.

“The ability of people to travel to use their skills, the ability of families to think that their children can stay in the communities that reared them and get valuable worthwhile jobs for a career, is what will be the end product of HS2.”

Nevertheless, Kelly concedes that those achievements in journey time reduction and the associated benefits are too distant for people to say it is going to be a practical benefit that will happen in their lifetimes. “But that day will come. I am absolutely confident of that. And that is when people will begin to see where benefit lies.

“The industry needs to work together to make sure that that beneficial effect is felt as widely as possible. That is why HS2 cannot be seen as a standalone project, but has to be seen as not just part of the wider rail network, but of the wider transport network. And that’s why we need to think about the strategic.”

The next six months will be crucial. The General Election campaign will undoubtedly throw a spotlight on HS2 - and the impact it will have both locally and nationally.

“General Elections always change the weather, because that’s what they’re intended to do. Therefore, whoever is in Government, I have no doubt that we will once again have to explain why HS2 is necessary and demonstrate how we’re going about it in a confident and efficient way. That is right and proper. We will try and do that.”

Kelly is certainly taking nothing for granted: “I think that the moment you take something for granted is the moment in the project that you risk losing it. So we have to keep listening, keep responding, and keep talking to the people up and down this country who have begun to engage and who have begun to think of how they don’t just have to accept the status quo, as things can change.”

It’s a slightly unfair question as Higgins isn’t present to answer it himself, but some recent newspaper reports suggested that if the political support were not forthcoming, Higgins would leave his role. Is that a danger?

“All he was doing in front of the Transport Select Committee was pointing out the factual position on his contract. And - not wanting to sound presumptuous about what a future Secretary of State might decide or not decide - I think that was over-interpreted, if I could be so bold.”

“I think you had other words for it at the time!” Kelly is reminded by Ruse.

“I’m being diplomatic!” replies Kelly.

The point, as Higgins has always said, is that he absolutely needs political support to do this. “A project like this demands consensus, but we should never take that consensus for granted.” So if the political consensus was to disintegrate, would it make any difference who was in the post of HS2 chairman?

“I think that absolute political consensus is absolutely vital. But what’s also vital is that we maintain the understanding of local politicians up and down the country, because HS2 is one of those projects that is in the national interest, but also of very particular local interest. Therefore we have to try and maintain that wide understanding.

“It will not mean that we will have everybody’s support for everything we do. But I hope there will be a general understanding of why we are doing what we are doing and why we’re recommending what we’re recommending, even if people don’t 100% agree with it.”

Liverpool is one example of that understanding, continuing with its ‘20 Miles More’ campaign. So too is Stoke, which came late to the party with a last-ditch attempt to have the route of Phase 2 (on the western arm of the ‘Y’) diverted through the city.

“Both Liverpool and Stoke will benefit from us going further north,” says Kelly. “Would they both like different particular outcomes? Yes. We have to make the right judgement and make the recommendation that the Secretary of State has to decide.

“It is the difference between today and this time last year that is foremost in some people’s minds. This time last year was about particular local concern and then they thought about the overall strategic interest.

“I think people have now begun to accept the strategic interest, while still wanting to look after their local concern. But I think people are prepared to accept that it will benefit the North and the Midlands in a way they hadn’t perhaps expected from last year, while they still work on their particular concerns.”

Was Higgins’ decision to involve Crewe earlier in the programme a game-changer? It could be argued that this was the moment when things began to change in terms of getting the support and wider engagement with the project.

“I think there was a fear that this was a way of getting to Birmingham and then the political impetus behind the project would stop. By saying that we wanted to take it further north sooner, people began to accept that we were serious about the ‘why’.”

Kelly believes this was set out in Rebalancing Britain, with Higgins going back to basics, and asking the question: ‘is the why actually justified?’ It set out looking at the current demand picture, but from the West and East.

“I think people now accept that we recognise that the rail game-changer is reducing the journey times to Leeds and Manchester and the places in between. Incrementally, you cannot do that.”

Talk of closing parts of the West Coast Main Line over Christmas is just palatable - but to have all the main lines closing for essential major engineering works, as more and more demands are placed on the railway, is unthinkable. Engineering works are a massive disruption and not something Network Rail likes doing, but increasingly the network is forced to take such decisions.

“I think that people concentrated on speed - and speed is important - and time. But the third factor is predictability, knowing that if you turn up the train will arrive on time, leave on time, and get you to the place you want to be on time.” This all means that passengers won’t need to employ the ‘just in case’ scenario.

“I went from Hereford to Birmingham International Airport at the weekend,” explains Kelly.

“Train number one, from Worcester to Birmingham, was standing room only. For train number two, I got an earlier train just in case.

“Now, for HS2, that ‘just in case’ has gone. In my case, that will save me a couple of hours. And that worry, that anxiety, isn’t really worth the hassle.”

Kelly relates the current stresses of train travel to his earlier point about the importance of ideas and meetings mattering in a competitive economy: “That’s what will disappear. That’s what will make people more likely to go to a meeting and therefore more likely to contribute to an idea that will change things. That’s what’s important.”

At Leeds Civic Hall in October, Higgins spoke of his visit to Silicon Valley and his realisation that it wasn’t just the cluster of cutting-edge companies that made them meet, but the infrastructure.

“It was the Highway 101, it was the 22 miles that connected, that made it easier for people to socialise, to get together, to think. It’s that connectivity that we have to try and re-create,” he said.

“And that’s why East-West is important, it’s why cross country is important, Rotherham to Derby is important, the Nottingham to Birmingham journey is important. Going further north sooner took us into the connectivity argument, in a way that just going to Birmingham wouldn’t have done.”

Peer review: Jim Steer

Peer review: Jim Steer

Director, Steer Davies Gleave

If we needed reminding why HS2 isn’t like any other rail project, the very presence of Tom Kelly as HS2 Ltd’s Director of Strategic Communications is a pointer. They simply don’t come any more experienced in UK politics and negotiation.

His positions of respect for those affected by the project and recognition of the need to avoid complacency are borne, it would seem, from his years working behind the scenes on the Northern Ireland Peace Process. They are surely to be embraced.

I also liked his insistence on the need to keep up the flow of messages about why HS2 is so needed. Like him, I have found that one of the most effective devices is to invite consideration of what will most likely happen in its absence. As he says, a world without HS2 doesn’t come cost-free - we can all see damaging levels of congestion looming. With ORR reporting a year-on-year 9.4% increase in passengers at Euston, perhaps it is HS2 objectors’ complacency that needs to be challenged?

Listening to Tom Kelly’s take on the last 12 months or so begs the question of how much the shift in attitudes to HS2 is attributable to the appointment of Sir David Higgins. Who else would have had the insight and credibility to call for the creation of Transport for the North in his second report, adding that it should be tasked with producing a transport strategy for the North as a start of an overall national strategy? We have been fortunate to have Sir David as HS2 chairman at this crucial time, when the project and its wider ramifications are still at the ‘shaping’ stage.

The two Higgins reports this year (HS2 Plus and Rebalancing Britain) are, as Tom Kelly says, steps on a very long journey. No doubt - with Tom’s help - they have been run past Ministers before release. I don’t think further reports in the same vein are planned, so the question arises: how will further steps in the planning and delivery of HS2 be way-marked in a like manner, signalling important shifts and gaining renewed (cross-party) political support?

The recent report (Rebalancing Britain) was silent on the question of Euston, for which a review is under way with new senior leadership. Maybe the timing wasn’t right, but this is classic territory for Tom Kelly’s negotiating skills to come into play: dealing with tough budget constraints; with an anxious (if now engaged) local authority; concerns about the risk of years of disruption during the construction stage; the not-to-be-missed opportunity to fashion major surrounding redevelopment; the need somehow to make Euston and St Pancras work together for through passengers between HS1 and HS2; and dealing with the force that is the London Mayor and Transport for London.

Squaring opposing forces needs some Higgins-style strategic thinking. In this case, it also means looking overseas to see how the problem has been solved. There are no suburban trains at the buffer stops of Gare du Nord, just a line-up of high-speed trainsets. To build Euston on time and with disruption minimised, we need to take out as many suburban services as possible and provide them with (better) alternative destinations.

It can be done. We can use the planned Crossrail connection to the West Coast Main Line to achieve a similar outcome. This means services not only from Tring but also from Milton Keynes joining Crossrail, instead of taking up scarce space at Euston. And the Overground trains from Watford need to operate onwards to Camden Road and beyond, rather than add to terminal congestion.

It wouldn’t be too late for a new report on this subject in spring 2015. In fact, by then we’ll also have the outcome of the Davies Commission on Airports, so there is a real need for a southern dose of the new strategic thinking from the Higgins/Kelly team.

Tom notes the power of speaking with one voice, when he observes what’s happened in the North. We’re going to need the same for HS2 in the South, too, soon enough.

Peer review: Christian Wolmar

Peer review: Christian Wolmar

Transport writer and broadcaster

This fascinating interview is as revealing for what is not addressed, as much as for what is.

I was most struck by Tom Kelly’s view of the opposition to HS2. He seems to think that it comes from people who are directly affected by its construction, but he offers no insight into why there is a substantial body of people who (like me) have come out against the scheme when we are not affected by it directly. He does not mention - or seem to know - that there is a significant minority of people within the rail industry who doubt whether HS2 will provide anything like the benefits that its huge cost suggests.

He says nothing, therefore, about the roots of the problem and why the project still faces an uphill task in convincing the wider public.

There is, however, the occasional hint that he does realise why the scheme got into such a mess before his arrival at HS2. He says, tellingly, that the Rebalancing Britain report “went back to basics, and asked the question: is the ‘why’ actually justified?”

Indeed, but surely it was the failure to address that basic issue that lies at the root of doubts about the scheme.

It was first conceived as a sop to the environmentalist wing of the Labour party, when the party was in power and announced its support for the third runway at Heathrow.

Transport Minister Andrew Adonis commissioned a report with the route already predetermined by having to provide a potential connection with Heathrow, rather than starting with a blank piece of paper and asking the more fundamental question: How do we best address Britain’s transport needs?

Kelly also addresses another of the fundamental flaws that the promoters of the scheme are at last trying to address - its connectivity with the rest of the network.

The industry needs to work together to make sure that that beneficial effect is felt as widely as possible. That is why HS2 cannot be seen as a standalone project, but also as not just part of the wider rail network, but of the wider transport network. HS2 has, in fact, seen itself as a standalone project - after all, why is it not melded in with Network Rail, which (in the end) its tracks will have to be? Clearly Kelly is aware that this is a major issue, but it will require more than a bit of clever PR to address it.

Not surprisingly, there is quite a lot of PR gloss in Kelly’s utterings. The most laughable is his delight that the two supply industry conferences were ‘sold out’, which his PR man quickly corrects, saying they were free.

Well, with some £43 billion - possibly much more - available for spending, is it any wonder that a swarm of hungry predators are ready to feast on the HS2 banquet?

The question that has never been answered is very simple: ‘If we had £43bn or so to spend on transport, would this be the best way of doing it? Nothing in this interview suggests that it is.

Peer review: Professor Rod Smith

Peer review: Professor Rod Smith

Former chief scientific adviser to the DfT

There is no doubt that Tom Kelly faces a massive task in informing, educating and changing the public perception of the HS2 project. I hope he is not underestimating the mountain he faces.

I have worried that since the inception of HS2, no overarching plan has been produced. The widespread perception is that of a series of ad hoc decisions that have been made sequentially - a new railway to Birmingham, let’s extend it to the Northern cities, then connect across the Pennines.

But many questions remain: will Scotland ever be connected? If so, it seems essential that the East route is taken, linking the North East and Newcastle.

Why is the western route unpromising? There is no real population concentration north of the Liverpool to Manchester axis, and the terrain is difficult for railways - this was well-known in the middle of the 19th century!

How will the Welsh capital be connected? Will anything happen south of the Thames? What triangulated routes will bring resilience to the eventual nationwide system? How will the new railway help in the development of new cities? How will it contribute to the pressing question of airport capacity? (A good example is Birmingham Airport, which will be nearer in time to London than Heathrow is on the Piccadilly Line).

When the motorway system was conceived (and many years before it was actually built), such a national plan did exist. It would be my number one priority to do the same for the high-speed rail system, and so stimulate public awareness that this is indeed a national project - not just (as many people perceive) a white elephant to cut a few minutes off the journey time to Birmingham.

The capacity that the high-speed rail system will provide is its real selling point - a capacity that will have to deal with a rapidly growing population increasingly frustrated by congestion of the motorway and trunk road network.

How passengers connect to the system needs careful thought. The fringe of the city interchange can provide access without taking passengers on unnecessary journeys to the old city centres.

Above all, it needs to be very clearly communicated that although good transport is an essential contributor to a successful economy, it is not by itself sufficient. Local policy decisions will contribute to the success or failure of the new possibilities provided by the high-speed system.

Stations, pearls in the necklace of the railway, can act as magnets to stimulate economic development or become monuments to folly - it all depends on generating enthusiasms to effectively use the increase in land values that a new stations brings. Local and regional transport systems need to be realigned to act in a complementary way to the new network - the capacity of the new system will not be useful unless it is matched by enhanced and extended local distribution systems.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.