Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

Lewis Cubitt’s Italianate terminus for the Great Northern Railway at King’s Cross is a true gateway to rail services.

Four operators - two franchised and two open access (Virgin Trains East Coast, Great Northern, Hull Trains and Grand Central) - run from the station, and there are proposals for a third open access service to join them. They sally forth on just four tracks, dipping sharply in Gasworks Tunnel to run under Regent’s Canal before lines from Canal Tunnels merge in from the left, to be followed a little later by Moorgate lines coming from the right.

Both junctions add more trains to the route (those from Canal Tunnels from 2018), making the line busy with many trains. This congestion has prompted major improvements in the past - notably in the 1950s, when British Rail quadrupled the line through Hadley Wood, ten miles north of King’s Cross. More recently, Network Rail has added capacity between Finsbury Park and Alexandra Palace to create three passenger lines in each direction. Two then diverge at ‘Ally Pally’ to leave four on the East Coast Main Line itself.

But BR’s work left a two-mile section through Welwyn North as double-track and that provides the major constraint on the southern section of the route today. In the past there has been talk of quadrupling this section, but no current proposals are on the table. Such a project would be very expensive, and will very likely draw complaints about spoilt views of and from the magnificent Welwyn viaduct.

NR describes the Welwyn section as a bottleneck that limits services to 18 trains per hour. But back in 2010 it reckoned it was not worth adding extra tracks, saying: “The four-tracking of the Welwyn viaduct is not expected to resolve capacity constraints on the southern end of the route. Four-tracking would allow trains calling at Welwyn North to use the slow lines, providing an approximate two to three trains per hour increase in fast line capacity.”

Such a constraint could be tolerated, were it not for the pressure from the line’s current and prospective operators for more paths in which to run more services.

Thameslink is set to expand as a result of a £6.5 billion project to boost the number of north-south trains running through London, with Great Northern trains to Peterborough and Cambridge being added to today’s Bedford-Brighton service. This is a government project, with ministers providing much of the money and shaping the service they expect in return.

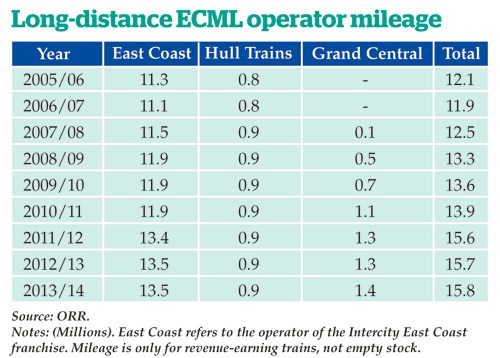

Stagecoach and Virgin took over long-distance ECML operations earlier this year (branded as Virgin Trains East Coast), promising government £3.3bn over the life of the franchise. This commitment is predicated on increasing the number of trains running, with new destinations being added to the route map.

The East Coast Main Line is the only long-distance route upon which open access has taken hold. Hull Trains was the pioneer, starting in 2000, and it now runs six return services a day. Majority owned by FirstGroup, it’s driving forward an overhead wiring scheme to Hull so that it can run electric trains in place of today’s Class 180 diesels.

Coming slightly later was Grand Central, which began a Sunderland-London service in 2007 and then added West Yorkshire trains to Bradford from 2010. Owned by Germany’s DB, GC and its sister company Alliance now want to expand its Yorkshire services and run hourly fast trains to Edinburgh, likely using Class 390 Pendolino electric multiple units (as Virgin uses on West Coast services from Euston).

FirstGroup also wants to run five daily London-Edinburgh trains, to compete with the air market - calling at Stevenage (for Luton and Stansted Airport custom) and Morpeth (for Newcastle Airport).

When the ambitions of all these operators are rolled together (see panel), this, bluntly, is more than the line can cope with, according to studies conducted by Network Rail.

Broadly, there is demand for nine or ten long-distance, high-speed (LDHS) paths per hour, but capacity for only eight. In these terms, the two to three extra paths that in 2010 NR said Welwyn quadrupling would provide appear sufficient, even though NR dismissed this option as inadequate.

It is rail regulator the Office of Rail and Road that must choose between them. But it faces a very difficult task. Open access operators are popular with passengers and score well in passenger surveys. They often offer direct services to destinations not served (or not served well) by franchised operators.

On the other hand, ORR must also consider the financial position of ministers and VTEC’s £3.3bn is hard to ignore in this context. ORR runs prospective open access bids through a test that determines whether those bids are ‘primarily abstractive’ - in other words, do they simply take too much money from existing services and passengers, rather than generating genuinely new custom to rail. Hence the emphasis placed on the air market by the two Edinburgh bids.

And while other services may run to stations not currently served by direct London trains, they could still be abstractive on a section of the ECML itself. For instance, London-Yorkshire could take revenue on the leg from the capital to Doncaster.

The ability of open access operators to run is enshrined in the legislation that privatised British Rail back in the 1990s. It provides for licences to be granted to non-franchised passenger operators, and allows them to enter into track access contracts with Network Rail if approved by the regulator. Open access operators are charged marginal access rates on the basis that they only incur marginal costs for Network Rail.

This works if there is spare capacity lying unused. The fact that perhaps another half dozen daily trains run does not add much to NR’s costs - they add little in the way of track wear and tear, and signallers and other staff are being paid for anyway.

But the difficulty comes if major upgrades have to be provided to create new capacity. When that happens, it cannot be considered that open access operators are using marginal capacity.

The ECML has already had a series of improvements delivered over the past few years (flyovers at Hitchin and Doncaster, new platforms at Peterborough, layout changes at York and the Finsbury Park work mentioned earlier).

But with capacity still tight, there is more to come, paid for from NR’s East Coast Connectivity Fund. This fund is £247 million over the five years of Control Period 5 (2014-19). Meanwhile, the company’s income from all open access passenger operators (which also includes Heathrow Express) in 2013/14 was just £24m.

It’s always difficult to split the money that government provides to subsidise non-commercial franchised services and the money that it provides directly to NR down to line and route level. However, ORR provides an annual financial report that attempts to shine some light on this complex world of railway financing. The latest report covers 2013/14, and shows that government provides just over a quarter of the total revenue for UK rail.

Delving into the figures for East Coast (VTEC’s predecessor) shows that EC’s share of NR’s government grant was £194m, while EC paid government £217m in premium payments. On this basis, there was a £23m surplus on government money. (EC also paid NR £117m in access charges in 2013/14).

In cash terms, the forthcoming improvements tip EC figures into annual deficit, but the improvements are enduring and are added to NR’s Regulatory Asset Base, on which the company is allowed to earn a return over a considerably longer period. But whichever accounting treatment is used, NR’s open access annual income of £24m (albeit it will rise if more services run) compares badly with the Government’s £3.3bn premium over eight years (which starts at £212m in 2015/16 and rises to £645m in 2022/23).

The presence of such substantial sums of money skews the argument in favour of the Government’s franchisee and away from services that have a demonstrably popular passenger record. Research also suggests that the presence of competition on the ECML route has kept franchised fares in check, boosting the benefits that open access provides but also blunting the return that government could (and expects to) generate.

North of Newcastle

And it’s not just the London end of the line that generates tricky capacity decisions. The ECML north from Newcastle is twin-track. In its December 2014 capacity report, Network Rail was only confident in suggesting that there were three hourly paths available to long-distance services, and suggested a split between two London trains and one from elsewhere - either a CrossCountry (XC) or an inter-regional service, which could have originated from a trans-Pennine corridor.

With VTEC having already staked a claim to two London services, this might have raised a difficult decision for the third path. Some clarity of the Government’s intentions come with its tender document for TransPennine Express, which makes no mention of TPE services extending north of Newcastle.

With First and Alliance in the mix, ORR faces a decision over giving all capacity north of Newcastle to trains serving London, and thus cutting XC from Scotland. This should be possible with through ticketing, even with Advance Purchase tickets, allowing passengers to change from XC at Newcastle onto other trains. However, this flies in the face of passenger preferences to change as few times as possible.

That said, East Coast’s 2011 Eureka timetable rewrite introduced a similar concept. For many passengers travelling between stations north and south of York, it enforced a change at York for connecting services to and from intermediate ECML stations such as Newark, Retford and Grantham, allowing Anglo-Scottish trains to run non-stop between York and London. The ‘stopper’ simply ran between London and York, in a construct that could apply to XC services if they were to be cut back at York or Newcastle.

Introducing more open access could also break into the clockface timetables that have been grasped by railway companies in recent years and which are likely to continue to be pushed. However, it might well be worth terminating a few XC services at York or Newcastle to allow one of Alliance’s fast London-Edinburgh trains to run. But how do you decide?!

This is a matter of weighing one set of passenger benefits against another. Speed is valued, but railway operators seem to favour clockface, perhaps for their operational ease - although given the increase in advance purchase tickets, the concept is becoming less relevant for passengers because these tickets tie their holders to specific trains.

That increase is striking. According to the Rail Delivery Group, there was a 9.6% increase in ‘AP’ tickets in 2014, rising from 55.8 million journeys in 2013 to 61.1 million in 2014. Revenue has risen from £0.1bn in 2002 to £1.1bn in 2012. What’s less clear is the extent to which operators have discounted tickets to fill clockface trains running at times when they might not be commercially viable. In other words, using a path because it’s there, rather than because it’s needed.

That would suggest that if other services bring a more commercial prospect, then they should take priority, even at the expense of another operator’s clockface service. Perhaps the fast nine-coach London-Edinburgh filled with those transferring from air generates more revenue than a four-coach service filled with £10 fares. Clearly that example is extremely simplified and exaggerated, but it serves to make a concentrated point.

It also serves to show the degree of second-guessing that goes on in a railway that is neither public nor private. The private operator will make its plans based on revenue predictions to justify whether or not to run trains, but Britain now has a system whereby the ORR has to decide between competing plans from commercial operators and from those running the service the Government wants and thinks it has paid for. ORR referees a railway game, while the real competition comes from cars, coaches and planes.

Clockface timetables are a dated concept in an age of better access to information, particularly via mobile phones. It’s easier now just to check when the next train to your station runs and then catch it, rather than remembering that they run at twenty to and twenty past each hour. The concept of clockface is being implemented just as it becomes obsolete from a passenger perspective.

That said, the concept remains useful for railway companies, particularly as lines become more congested. Their predictable nature is easier to work with and they work well with ‘flighting’ (the concept of setting trains off a few minutes apart depending on stopping pattern - the train with the most stops being last in the flight).

In maximising capacity, timetables drag trains down towards the speed of the slowest, because that’s how you accommodate more services. It works against the fast train that tempts passengers away from aeroplanes and thus grows the rail market, because that fast train absorbs so much route capacity.

In many ways, it’s the timetable equivalent of First Great Western having to cram as many airline seats as possible into its HSTs to satisfy government’s demands for commuters east of Didcot. That the same trains must also serve West Country holiday traffic, with families who would like to be around a table of four, is lost in the capacity argument.

Another downside of clockface services is that they can tie several routes together, making changes in one hard to implement without ripples affecting another. The difficulty of those changes becomes much harder as lines become more congested, which partially defeats the reason for clockface in the first place. Pity the timetabler trying to put the last line into a clockface - what works at one end of a line might be completely out-of-sync at the other.

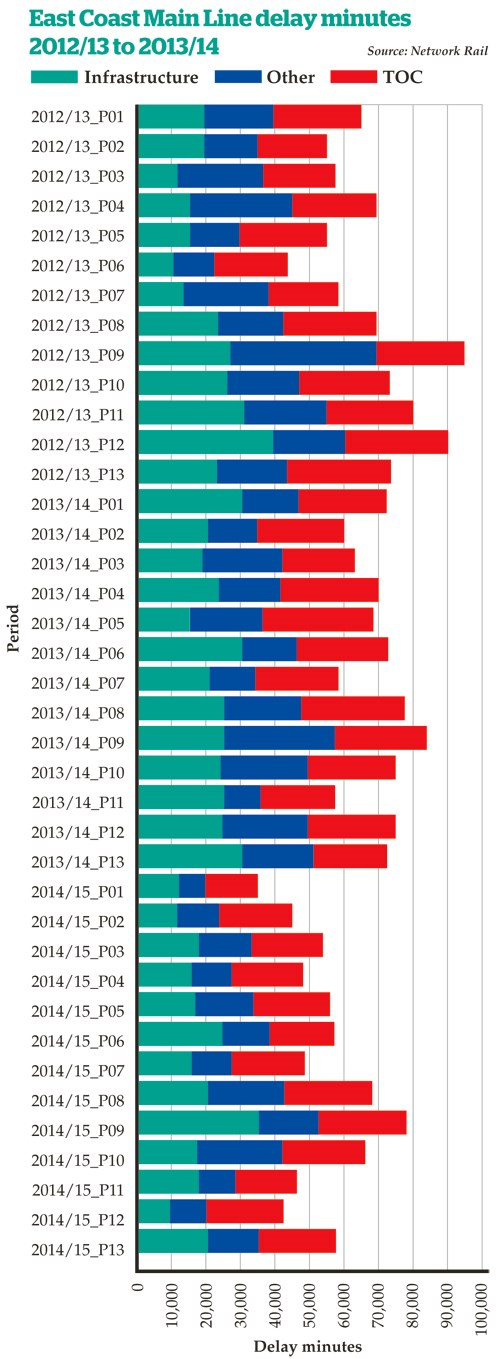

A busy clockface timetable also demands a reliable railway, both track and trains. In this regard, the ECML does not have a good record. For many years, it’s been on or around the bottom of the performance league table, although recent performance has been improving.

Adding more trains generally results in yet poorer performance. That’s certainly the picture that has emerged following the addition of a fifth trans-Pennine path in May 2014 - NR found that right-time performance fell by a thumping 17%.

The massive reorganisation of West Coast Main Line services associated with Virgin’s very high frequency timetable in 2008 led to a 15% fall in right-time running. An exception can be found on the ECML, where May 2011’s Eureka timetable resulted in a 1.5% increase.

Network Rail collects a vast amount of performance information for the route, classifying delays according to their cause. Some cause particular peaks - overhead line equipment tends to cause major delays when it collapses (up to 9,000 minutes in some periods), but this doesn’t often happen. In contrast, technical fleet (train) faults have caused at least 8,500 minutes in all but a couple of periods over the past two years.

Both are on declining trends, contributing to the overall increase in punctuality across the route. Both points and track circuit failures are also falling. On the other hand, signal failures are rising (an average of 1,000 minutes delay per period over the last year).

One rising trend that is expected to continue is that of passenger numbers, which have already doubled since privatisation. With Britain’s population expected to keep growing, rail numbers should keep increasing, even if the sector fails to win any increase in market share from air and roads.

In 2009, NR reckoned the increase over 2007-2036 would be between 34% and 78%, depending on the direction the country moved. Updated work in 2013 put the 2012-2023 rise between London and Leeds at 14%-48%, to Newcastle 12%-58%, and Edinburgh 14%-43%.

The response to these predictions has been to provide more rail capacity, hence the CP4 and CP5 programmes. Yet for the provision of roads this ‘predict and provide’ model has been discredited after many years of faithful application by governments, because it simply responded to demand rather than trying to shape it for the country’s benefit.

Predict and provide can be justified if its application makes Britain a better place (not the easiest thing to measure). Taking rail as a greener transport option than road or air, providing more rail capacity in order to make UK transport greener overall could be a valid policy.

The increase in passenger numbers since privatisation has been coupled with an increase in rail’s market share since then, from a low of around 5% to nearer 8% today, perhaps justifying predict and provide.

However, in its 2012 High Level Output Specification for 2014-2019, the Department for Transport makes no mention of increasing modal share. There is no mission to cut short-haul air with fast journeys of the sort proposed by Alliance and FirstGroup. Instead, it calls on the rail industry to deliver “dynamic, sustainable transport that drives economic growth and competitiveness” while reducing costs by £3.5bn, to make it “more financially sustainable and lessening the burden on farepayers and taxpayers”.

It does specify an increase in capacity for freight and franchised passenger services. It also directs that up to £240m be spent to improve the East Coast Main Line.

That’s very close to unjustified predict and provide.

Peer review: Michael Holden

Peer review: Michael Holden

Chief Executive, Directly Operated Railways

Philip Haigh has neatly summed up this Gordian knot, which has been metaphorically trussed up with a pretty pink ribbon and deposited on ORR’s doorstep.

Let’s start with the infrastructure enhancement schemes, of which there are still too few to enable the route to be properly developed. The Werrington flyunder is a critical next step, proposed for CP5 but not yet committed. This would enable grade separated access for freight trains bound for the GN/GE Joint Line (which has recently been upgraded at significant cost), thus enabling more paths for fast trains between Peterborough and Doncaster.

But there are a number of other flat junctions on the route that also restrict capacity and act as timetabling and performance hot spots - the flat crossing at Newark prevents a proper service operating between Lincoln and Nottingham; at Doncaster itself, where trains cross on the flat to and from the Thorne line and the West Riding; and Skelton Junction, north of York. All these need grade-separated junctions to unlock desperately-needed capacity.

The currently abandoned Leamside route needs re-opening to unblock capacity between Darlington and Newcastle. North of Newcastle, there is a need for shorter headway signalling and improved overtaking facilities. Finally, Portobello Junction, east of Edinburgh, needs rebuilding as a double junction.

Then there is the use of capacity that government can control through franchise specification. At the south end of the route, a 125mph higher-capacity commuter service ought to be specified to service Huntingdon to Newark, with extensions to Spalding and Lincoln (with associated electrification);. Thameslink trains should turn round at Huntingdon with a reinstated dive-under. And Thameslink peak trains running north of Welwyn Garden City should all be specified at 12 cars, to optimise use of capacity. So franchise re-specification could make much more effective use of capacity over the Fens and through the two-track Welwyn section.

Taken together, these schemes would provide enough capacity on the whole route to operate all the existing franchise and open access applications and retain a CrossCountry service hourly to Scotland - but require another billion or two of (recoverable) investment and perhaps ten years to build.

Until such time as all this might be achieved, how should ORR determine the existing applications in its in-tray? The answer: with the greatest of difficulty and in the expectation of legal challenge whichever way it jumps!

This goes to the heart of the railway legal structure set up to enable privatisation. Open access is enshrined in the 1993 Railways Act, but the harsh reality is that it is really in conflict with the franchised system, at least in respect of long-distance services. Network planning is really difficult on a railway where there is no financial level playing field. Open access players pay only their marginal costs on the network, whereas franchisees contribute towards the fixed costs, as does government through the network grant. It is time that this is unpicked, otherwise this problem will recur and worsen.

Cutting the Gordian knot will require bold action by ORR to plump for one side of this argument or the other. I hope we don’t get an unworkable compromise outcome. Longer term, the solution is more investment in capacity and structural reform of capacity planning and charging.

Peer review: Richard McClean

Peer review: Richard McClean

Managing Director, Grand Central

uietly and in the background, the East Coast Main Line has progressively and incrementally enhanced its capacity and capability year after year. The next chapter of the ECML story is about to start - and what a great story it is, with the prospect of the fastest ever Anglo-Scottish services, fleets of new trains, more direct services to London from more regional centres, and a massive upgrade to the commuter services into London. Just what the Northern Powerhouse needs.

At the heart of this success story has been the dramatic and continued growth in the number of passengers attracted by the high level of customer service and good value offered by the inter-city operators.

It is right that capacity on the route should be expanded to allow this good news story to continue, rather than to see it choked off just at the moment when rail is able to take a good shot at the last major domestic inter-city market that hasn’t been transferred from air to rail.

In this context, there are two separate debates:

- Which service proposal delivers the best product to that key market - a ‘more of the same’ option, or one that raises the bar to the point where rail is the natural option for Anglo-Scottish travel, just as it is now for Yorkshire and the North East?

- Is it better to serve these highly commercial markets through state-sponsored monopolies, or by opening up the opportunity for passengers to have a real choice between operators?

Network Rail’s capacity study shows how it is possible to develop strong timetables that maximise the benefits from the investments made on the route, balancing the requirements of different service types and the needs of different end users.

We shouldn’t be too surprised at that, as it has been happening for years. We have operated mixed traffic routes with everything from 60mph freight trains through intense suburban service patterns to long-distance high speed trains. Despite suggestions to the contrary, it has not been necessary that all the trains are painted the same colour, or are subject to the rigours of a single “guiding mind”.

Of course, there is the real question as to how the commercial services running on the network pay a suitable contribution to the total costs of the infrastructure they use. There is no doubt that they should, and efficient ways of achieving this can be found through looking at how access charges are structured or the establishment of direct levies on commercial operators.

However, it is also clear that using a process that was designed to subsidise socially necessary services that can’t cover their own costs through direct revenue is highly inefficient, places massive risk with the taxpayer, and deprives passengers the palpable benefits of real choice in the services they can use.

The ECML has the capacity to provide the best service ever offered to passengers, and it has a host of world-class operators queuing up with innovative service plans that will blow the socks of passengers. It would be a crying shame if the internal bureaucracy of the rail industry got in the way of unlocking all of this!

Peer review: Councillor Chris Steward

Peer review: Councillor Chris Steward

Chairman, Consortium of East Coast Main Line Authorities

Philip Haigh succinctly sets out the challenge facing the Office of Rail and Road in deciding how to utilise capacity of the East Coast Main Line to best effect. At the Consortium of East Coast Main Line Authorities (ECMA), we think the ECML’s economic potential should be a key consideration in its decision-making.

Our research (The Prospectus for Investment in the East Coast Main Line) into the economic impact of improving services along the ECML shows a potential GDP benefit of £5 billion. (ECMA defines the ECML more broadly than just London to Edinburgh in its national economic role - we are also concerned about the connectivity of places such as Aberdeen, Bradford, Grimsby, Hull, Inverness, Leeds, Lincoln, Middlesbrough and Perth.)

This figure rises by a further £4bn when HS2 services run to York, the North East and Scotland. Consequently, businesses require a more reliable railway service with faster journey times, greater infrastructure resilience and improved connectivity between locations.

We know that the economies along the ECML contribute over £300bn to the UK’s GVA each year. These economies contain industries that are of various types, sizes and propensities to travel. Growth centres are located along the whole route, in fields such as finance and business, life sciences and biotechnology, tourism, oil and gas, and advanced and applied manufacturing. Business leaders say they need better links along the ECML to release the potential of these centres, statements that have been underpinned by our analysis of the potential agglomeration and labour market benefits.

From the evidence, we have developed a set of conditional outputs that (if fully met) will generate significant potential economic benefits. We have deliberately asked the rail industry how best to achieve these outputs, rather than merely coming up with our own schemes, and we are contributing to the imminent Network Rail East Coast Route Study.

The outputs are based on having a reliable and resilient infrastructure, and are as follows:

- Eight long-distance high speed trains per hour each way to London by 2019, with a ninth train per hour to Cambridge from the north.

- Through HS2 services beyond York.

- Journey time improvements along the whole ECML, including internal journeys in Scotland. More direct services serving London from places off the core East Coast Main Line (for example, the Virgin Trains East Coast bid for trains between Middlesbrough and London).

- Better connectivity from places near London (for example, Stevenage) with other places on the ECML.

- A more professional, office environment on each train, including continuous free WiFi, good mobile phone reception and sufficient seat capacity.

- Each station of a quality to actively encourage people to travel by train and enable it to be the “gateway” reflecting the economy and community that it serves.

- Gauge enhancement to ensure that freight trains can carry W12 size containers to and from key ports and strategic rail freight interchanges.

- Additional line capacity to allow more, longer, freight trains to run efficiently without detriment to passenger trains.

Philip writes of the need to justify investment, and that the sum currently being invested in the East Coast Main Line is close to being unjustified.

My view is that the strategic case for economic growth along the ECML exists and that the investment is needed to help realise it. Indeed, my view is that the development of solutions by the rail industry may well mean that more funding is needed to secure the conditions for the stronger economic growth.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.