Download the graphs for this feature.

In a privatised rail industry whose first 20 years has frequently been hobbled and compromised by a chronic lack of effective leadership, I had to smile wryly recently when a prominent private sector chief said he was “concerned by the growing number of leadership bodies”.

At the annual Atkins company drinks ‘ bash’ at the St Pancras Grand, recently departed Rail MD Douglas McCormick was addressing his couple of hundred guests when he voiced his concerns about (but without actually naming) the Rail Delivery Group and the rather newer Rail Supply Group.

He was clearly concerned about a long period of no effective industry leadership being followed by the arrival of the RDG and RSG. He could, of course, also have added the new bodies currently emerging at the Department for Transport - the Office of Rail Passenger Services, the Rail Executive and the Franchise Advisory Panel.

Maybe we shouldn’t raise an eyebrow at this sudden desire for control - it’s long overdue that the railway should have a ‘guiding mind’ other than the Department for Transport.

And this leadership vacuum has gone on from the earliest years. I have been asking “who speaks for the railway?” in RAIL Comments for more than a decade now - especially in the chaotic and febrile aftermath of a fatal accident, or latterly with regard to fare increases, structural issues or costs.

The industry’s lack of leadership led to industry commentators (including myself, Philip Haigh, Christian Wolmar and Roger Ford) frequently being sought out to explain and interpret a confusing or controversial development, by an always curious, invariably persistent and frequently downright hostile wider media. Ironically, it was former Railtrack Chief Executive Gerald Corbett who summed up the inevitable outcome of the industry’s failure here: “If you don’t set the agenda,” he said to me, “then some other ****** will!”

I believe that many of the industry’s ongoing reputational problems (especially around fares) were triggered by this lamentable lack of leadership, and then made worse by a condescending PR approach that treated the media and its readers/viewers like fools. The industry has paid a heavy price, for example, for its head-in-the-sand refusal to amend its ‘kick-me’ annual fare increase approach, in particular.

To use the now discredited ‘flex’ system to ruthlessly jack up fares on busy routes while leaving lightly used routes alone, in order to stay within the required average, was always cynically manipulative.

What was worse was the Association of Train Operating Companies’ ludicrous claim that it “didn’t know” what the maximum fare increases were. Even my schoolboy maths knows that if you know the average, you must have started with the highest and lowest fares.

ATOC clearly believed that if it persisted with this ludicrous PR policy for long enough, then passengers would come to regard the annual January hike with the same weary, accepting resignation that council tax increases are regarded each year. That will never happen, and it was foolish to ever believe it would. Meanwhile, the reputational damage has been immense. Thank goodness that in the pre-election politicking, the ‘flex’ that led to this was abolished.

Can RDG put this reputational damage right with regard to fares?

Let’s take a moment to remind ourselves of how we got to where we are. RDG emerged post-McNulty, with a focus on what this report saw (rightly) as excessive unit costs. RDG comprises Network Rail, the principal passenger franchise owning groups, and representatives from the larger freight companies. RDG is self-created, with self-appointed members, has no formal accountability to anyone, for anything, and at the outset it chose to exclude the massive supply industry from its top table.

RDG is uncomfortable (and can be prickly) with descriptions like this. But it’s nonetheless true, and is important given that it claims to ‘speak for’ and ‘represent’ the entire industry. Contractors and suppliers are represented in second-tier RDG structures and workgroups, but are not members of the top table.

At first this caused massive discontent among those who believed themselves to be excluded from a leadership body for an industry in which they have very long-term interests, but which was about to be led (as they saw it) by short-term franchise holders of insufficient experience and questionable ability and credibility.

One high-profile early critic effectively summed up this view: “If this was the aviation industry, you would not have an organisation speaking for the whole industry which consisted entirely of airlines - including some relatively tiny companies. You’d want Boeing and Airbus in there alongside BA, Ryanair and Flybe. Otherwise it would be a nonsense.”

Others who saw themselves as ‘left out’ were, behind the scenes, spitting blood about the RDG’s selective approach to membership, with its focus on (as it was put to me) “here-today-gone-tomorrow passenger operators”, to the exclusion of massive companies with billions of pounds, euros and dollars committed for maybe the next 30 years.

One particular critic - a very large global multi-national with major UK interests - was especially blunt: “Why the hell should National Express, with a single, tiny TOC on the north bank of the Thames, have a full seat and voice at the top table, while we are restricted and relegated to an obscure back-room working group?”

I wrote several RAIL Comment pieces sympathising with this view, especially in view of RDG’s near-total silence during the darkest days of the HS2 debate in the summer and autumn of 2013.

How, I asked back then, could a body that boasted of its representative leadership credentials banish the industry’s most committed, involved and long-term players to the dressing room while failing to support (or even comment in detail on, for several months) what will be Europe’s biggest civil engineering project - building HS2? You cannot ‘talk the talk’ without ‘walking the walk’, and at that time RDG was consistently failing the credibility test.

Not for the first time, my phone and email in-tray buzzed with confidential messages of support for a view that seemed to command significant agreement in private but a good deal of tight-lipped frustration in public.

In dealings with the DfT, I sensed a similar unspoken frustration, and was beamed the message that they had made clear to RDG that the suppliers must not be thus excluded. Even though it was all done by raised eyebrow and implication (in true Sir Humphrey style), the message was clear.

Any criticism of this situation was routinely, if politely, dismissed by RDG and those around it. But behind the scenes, things were happening. There had been a skittish early spell, when it was undoubtedly difficult to keep all the key players even in the room, let along talking to each other. And RAIL was discreetly urged to ‘lay off’, in order to give Tim O’Toole a chance to bring the nervous factions together more permanently.

Let’s not forget the weeks and months after the West Coast franchise fiasco. Having Virgin and FirstGroup sitting across the RDG table from each other as full members of a relatively small leadership group must have been challenging for everyone.

There followed a period when former DB Schenker Rail (UK) Planning Director Graham Smith acted as Director General (a one-man, full-time staff) - a period during which it was also reported that RDG had launched a very serious bid to take over the Rail Safety & Standards Board (RSSB). The intention was to give RDG an executive and back-office staff to give its role and presence solid credibility, but this did not come to pass, and eventually RDG won its full-time staff, presence and critical mass by merger with the Association of Train Operating Companies.

Meanwhile, the Rail Supply Group (RSG) was born, to better represent supply chain interests to government (and RDG!).

Overnight, it seemed, the high-profile angst and dissatisfaction gave way to a joint love-in and charm offensive. Supplier critics who once sought to highlight RDG’s unrepresentative nature were suddenly full of praise. All talk was now of integrated, complementary effort, teamwork and partnership. The critical companies of a few weeks before were now love-bombing me with messages of support for RDG. It was extraordinary.

After two and a half years as chairman, the clubbable and effective Tim O’Toole, whose considerable business and interpersonal skills had prevented RDG melting down into a talking-shop group merely serving their own business interests, had given way to Stagecoach Chief Executive Martin Griffiths, who took RDG’s top job.

At the time, I knew Griffiths only by reputation (effective, driven, successful, unflinching), and so asked for an on-the-record interview to find out where RDG (and RSG, come to that) was going. This was immediately agreed to, and was followed up by a dinner invitation with not only Griffiths, but also RSG Industry Co-Chairman Terence Watson (Alstom’s UK president and transport managing director), accompanied for good measure by RDG Director General Michael Roberts, who still runs ATOC as its Director General but who is now frequently the voice and face of RDG’s media output.

I therefore approached this interview with considerable scepticism. On the one hand, I support 100% the notion, aims and reality of the RDG - it just seems to me to have misfired from the outset, leading to disappointing outcomes and limited impact. It’s to RDG’s credit, given the strength of my criticism, that its officers were so relentlessly welcoming, cheery and (on the face of it) open.

In Round One of our on-the-record encounter, we met at ATOC’s rather swish tower block offices in the City of London. Martin Griffiths was throughout friendly, jovial and refreshingly ready to answer any question, so we started with a simple one.

What is RDG actually for?

“The Rail Delivery Group was a response to Sir Roy McNulty’s review of the efficiency of the rail industry - but we are going beyond that now,” he replies.

“RDG is about strategic leadership, and for me its greatest strength is that for the first time we have the chief executives of train operating companies, freight companies and our partners at Network Rail sitting together discussing the major issues affecting the railways today, and thinking about how we deal with the positive challenges that we have over the next 20 years.”

Industry-wide solutions

That’s great in outline - but specifically?

He answers: “How do we actually take the railway forward and accommodate the growth that I think we will get - and what does that mean for capacity, rolling stock strategy and efficiency?”

“Some of that the private operators will have their own views on, and some of that will be in the domain of bidding and what you can do as an individual company. But a lot of those issues are industry-wide, and so we need to find industry-wide solutions.

“For years we have had this adversarial relationship with Network Rail, about whose fault was it, but the passengers really don’t care. Their issue is: ‘why was my train late and what are you going to do about it?’ Unless we are prepared to find the best answers, we are not going to make any progress.”

But surely this has been obvious for years? The silo thinking he’s talking about has been highlighted by commentators from the first days of the newly privatised railway in the mid-1990s.

Griffiths does not disagree, which, he says, explains RDG’s search for the executive basis it found in its marriage with ATOC. He claims that the operating community has matured, and that there is now a real desire for partnership and collaboration (not least with Network Rail) on those areas of genuine industry-wide interest.

“We just didn’t have a structure,” he explains. “That’s why last November we decided to put together a strategic leadership organisation with an executive capability that can allow us to more aggressively pursue some of the things on our agenda.

“So we merged with the existing ATOC team, seconded some Network Rail staff, and created that executive structure under Michael Roberts as the director general.

“For the first time we felt we had real firepower, and although we still have a way to go on the journey, we need to think through exactly the role that we play. We need to highlight what we bring, and work in partnership with whatever government we have. One of my goals as we approach the next General Election is to see how we do that in the short term, while more importantly making that relationship work for the industry in the longer term.”

Griffiths is honest about efficiencies. He is, for example,cautiously optimistic that Network Rail will deliver as planned in Control Period 5, and that the 20% efficiency savings promised to the Transport Select Committee by then NR Chief Executive Sir David Higgins and then RDG Chairman Tim O’Toole will probably be delivered. And he candidly concedes that some potentially major savings highlighted by McNulty are theoretically possible, but practically unlikely in today’s political context.

“The passenger train and freight operating companies continue to strive to be as efficient as we can,” he says carefully. “But I’ll be honest, Nigel, there are areas like Driver Only Operation in which yes, theoretically you could say there are efficiencies - but in terms of the wider industry and industrial relations, they are not necessarily deliverable.”

At least that’s an honest answer, even if the missing words are “…until the Government gives us the required support and air cover”.

Because he’s right. There ARE very significant efficiencies to be had, although the sotto voce instructions to TOCs from government has thus far been: “Do what you like, but don’t have a strike.”

This is one area where Whitehall plays a frankly sneaky game. It often criticises TOCs in public for not pursuing savings, or for perceived rip-off fares, while behind the scenes either denying the air cover needed to pursue DOO or (as regards fares) playing a key role in driving fares up and then keeping quiet while TOCs take the rap.

To be taken really seriously, RDG needs to go further than Griffiths’ rather coded language. But of course, no one wants to ‘bite the hand that feeds’ by criticising DfT. I welcome Griffiths’ small steps and appreciate the tightrope he walks - but RDG needs much sharper teeth if it is to be what he clearly wants it to be, in my opinion.

In Griffiths’ own oft-repeated words, RDG has “a long way to go”, so we’ll continue to watch and wish him well in this endeavour. He is especially pleased with more non-contentious work done by RDG (and led by Tim O’Toole) on asset management and supply chain management. He believes RDG has gone way beyond what it was believed was possible here.

I ask about RDG’s credibility and authority, given its non-statutory, self-appointed nature and its accountability to no one. The answer is urbane, but I’ve touched a nerve.

“I think you’re unfair to say it’s self-appointed,” Griffiths answers. “It was a leadership group that came together - was asked to come together by the Government and by DfT. The then Secretary of State said we needed to see how the industry could respond to the growth and efficiency agenda, and also provide the right leadership.”

Unsurprisingly, given my scepticism and Comment page criticisms of the past few months, Griffiths heads off what he believes will be my next question.

Suppliers are represented

“I’ve heard the challenge about why some of the supply chain and ROSCOs are not in RDG. But at the end of the day, in any organisation and in any industry, that doesn’t mean that these people aren’t important, or involved,” he explains.

“But if I had everybody who wanted to be on the RDG around the table we would fill Wembley Stadium, we’ve had so many knocks on the door!”

I counter that if this was aviation, any similar Delivery Group would most likely tell only half the story via membership of Ryanair, easyJet and Flybe - you would also want Boeing and Airbus. Surely, including suppliers would deflect the accountability argument and enhance RDG’s credibility?

Griffiths is having none of it!

“Just to be clear,” he counters. “Suppliers ARE represented, in a number of RDG’s work and sub-groups, and their role is very important. That’s working well, and the other thing that we encourage - and I’ve been speaking to Alstom’s (and the RSG’s) Terence Watson about this - we now have a clear working relationship with them, so RSG will come and regularly update RDG on what they’re doing and their priorities.

“Equally, my colleague Tim Shoveller is on that Rail Supply Group and is my alternate on the RDG, so we have full interaction there.”

This duplication still strikes me as odd - and expensive - to a private sector that normally avoids excessive costs like the plague. I remind Griffiths that I was sought out and lobbied by big suppliers who were, frankly, spitting blood about exclusion from RDG. Isn’t RSG’s very existence proof of my point?

“I can’t speak for them - I can only tell you about the very constructive dialogue I’ve had with someone like Terence - and he didn’t run out and form the RSG because he wasn’t on RDG,” says Griffiths. (Which is an interesting answer to a specific question I didn’t even ask!)

“It wasn’t like that. His strategic agenda for RSG was to say we are punching way below our weight here. He is rightly saying that while some of the companies involved are not UK companies, they do operate here, have big workforces, and should have a bigger voice.

“I think that RSG’s formation was more a response to some of their internal issues, rather than their supposed exclusion from the leadership of the industry. I think we work very hard to make sure that they ARE included - but you just cannot have everybody around the big, wooden table.”

TOC representation

I don’t disagree, but point out that prioritising isn’t difficult, in this instance. There’s plenty of TOC representation at RDG - but is it right that National Express, for example, with its one very small Essex Thameside operation, should occupy a full seat at that table while the giant multi-national Alstom, for example, or Siemens, which has billions of euros of ‘skin in the game’ for maybe the next 30 years or so, is excluded? It just doesn’t bear logical scrutiny.

“And they are very important, I’m not belittling them or their contribution at all,” replies Griffiths.

“We have a good relationship, and in terms of some of the specific work loops like rolling stock…”

My repeated question as to why not have them at the top table merely elicits the repeated answer that the table isn’t big enough.

Griffiths isn’t giving a millimetre: “It doesn’t mean the relationship isn’t important, and it doesn’t mean that we don’t want to leverage off their skills and their knowledge at the right time.

“You’re using the opportunity to say National Express has a small franchise. Interestingly it has had that franchise confirmed and renewed, and it is going to be bidding for more. National Express, over the long term, has been an important player in UK Rail.”

He continues: “You could argue for better or for worse, but we think it’s been working, and we have to make sure that it is an inclusive group while recognising that at the end of the day you just can’t have everybody. We think we have a good structure for leading the industry, going forward.”

It’s certainly true that since the formation of RSG, the cacophony of supplier anger about RDG has receded. But I have to ask the obvious question: will RSG and RDG merge? Evolve into a single organisation?

“There is certainly no plan for that at this point in time,” says Griffiths. “What we want to do is work together for the benefit of the industry and all its stakeholders.”

We move on. I ask how a group of competing TOC owners, all with clear legal and corporate responsibilities to put their shareholders’ interests first at all times, can collaborate fully or effectively in the way we all want to see. Given that we’ve established that membership does not comprehensively represent the industry as a whole, can we be sure that corporate rivalries and individual responsibilities will not hamstring real progress on matters that affect everyone - especially those denied membership?

I mention that the atmosphere around that famous table must have been thick with tension between Virgin and First, during the West Coast franchise debacle. Given what they were saying about each other in public, how could they collaborate effectively in private?

“You’re right,” says Griffiths. “There will be times when different groups will have their own commercial interests to think about, protect, look after - whatever way you want to phrase it. But generally, in my experience - and I have been there largely from the very beginning - I think I’ve been at every meeting, and what’s discussed behind closed doors stays behind closed doors.

“But I think I can be very honest and say that largely we’ve had only positive discussions. We recognise that sometimes we have to deal with our own commercial interests, but when we are here we are sitting trying to represent the rail industry and do the right thing for the industry as a whole.

“Even out of the awful West Coast procurement came some real positives, and I would never have thought that was possible! I was tasked to investigate how the industry could respond to the challenge of the Brown review. We wanted a collective response through RDG and, as you say, at that time things were sore.

“FirstGroup and Virgin both felt very aggrieved about the franchising process - but RDG was at the forefront of an industry submission to Richard Brown’s review, and I was actually very proud of that. For me that was one of the first big tests of our ability to put our personal positions to one side, and come together and say ‘if we don’t fix this we might not have an industry, because we really can’t afford not to have a procurement process that is not fit for purpose’.

“Everybody came together and participated in it, and I think the industry takes great credit for that.”

High Speed 2

I ask how his claims about RDG’s industry leadership dovetail with its silence over a very long period about HS2, which will be Europe’s biggest infrastructure project? Long before RDG’s birth, ATOC was extremely lukewarm (if not indifferent) about HS2, which it clearly regarded more as a competitor for government funds.

“We will look to try and address that. I hope you will have seen a stronger approach through a number of different publications, articles and reviews. When it’s appropriate for the RDG to speak we WILL speak. We will have a voice on these issues, and I think that’s important.”

Although there’s no mention of RDG on the wall in ATOC’s reception, there’s no mistaking the bigger presence and increased momentum to its activities since the ATOC merger. Does RDG now have the critical mass needed to make a difference (alongside a solid PR policy), and the courage to pursue it?

“It has helped that we now have Michael and his team to help put a day-to-day support structure in place,” he agrees.

“There was no doubt that was a challenge over the previous 18 months. I have a lot of time for Graham Smith, who was a kind of one-man band supporting Tim, but that was never sustainable. Now we have the full effect of the ATOC resource behind us. That makes a huge difference in our ability to really be on top of issues.”

Is it correct that RDG made an attempt to merge with or even take over RSSB, in its search for critical mass and credibility?

“Whether you call them takeovers… mergers… for me there is still a debate to be had, and it is still ongoing about the whole industry structure. The one thing I said at the very beginning here on RDG is ‘if all we do is form another talking shop, and we don’t start to streamline the structures and decision-making, then we have failed’.

“If we were to put the industry structure on that whiteboard behind you, with all the different overlaps, I think we’d agree that you would not run a normal company or corporate structure or any other body like that.

The industry is still sub-optimal, so we’re working closely to try and cut out some of the duplication. If you’re showing leadership that’s what you need to do. I think we’ve made some progress, but we are nowhere near finished.

“So here’s my RSSB feedback to your question, because I haven’t answered it very well: you can’t lead the industry if you don’t have an oversight of safety - you just don’t. So whether that responsibility comes through the Network Rail side of RDG or whatever, it is important that RDG is sighted on RSSB’s plan, work and process, because RSSB is so critical.”

So there was a discussion about taking over RSSB?

“There is an ongoing discussion about how we best interact with RSSB,” he replies, which still doesn’t answer my question. “It would be misleading to say that it was a merger or a takeover - but how do we make sure we are each sighted on what we are doing?

“That discussion has started with RSSB Chief Executive Chris Fenton. Mark Carne, from RDG’s point of view, is a sort of sponsor for RSSB, and that works well, I think.

“Mark is totally focused on safety - particularly workplace safety - and that’s good because that underpins everything else in the rail group. We must continue to get that right.”

Having got his feet firmly under the table at RDG, how does Griffiths see its current state of development? Is he happy with its rate of progress?

“It’s only six or seven months since I took over, but it seems a lot longer than that! And yes, I am happy with progress,” he says.

“I actually feel that there’s an awful lot going on not only in terms of the areas that we are looking at - technology, people, asset management, stations, franchising - but also in terms of the more public things that we have been getting involved with. This includes HS2, our ability to speak to both current and potential policy makers.”

This is a crucial area of work that the industry as a whole has not done well since privatisation. Indeed, this is one job (research and development is another) that the unified British Rail did especially well - and much better than the privatised railway to date.

Its ‘This is the Age of the Train’ TV campaign entered the public consciousness so deeply that it even sparked a me-too derivative promotional ads campaign among Britain’s steam and heritage sector, under the heading ‘This is the Aged Train’ and featuring one of the Bluebell Railway’s steam locomotives. And while we look back in horror at Jimmy Savile now, at the time the series of TV ads he fronted were powerful and effective in marketing the railway as a whole.

Since privatisation, fragmented agendas, budgets and strategies have meant no overall voice for the railway in either promotional or PR terms, so I welcome and applaud RDG’s attempts to raise the level of understanding about railways. A series of press releases giving context and wider understanding is long overdue, and (I believe) crucial in the long-term task of increasing awareness about our railways.

Does Griffiths see RDG’s job as speaking to policy makers or the public?

“Both,” he answers, without hesitation. “Clearly we have a job to do to respond to the public, and make them aware of what’s going on and respond to their needs.

“But yes, it is crucial we speak to policy makers both current and potential. We need to make sure that if politicians want to change or tamper with the industry structure, I would feel that I had failed if we didn’t give them the right information, facts and evidence - rather than rhetoric or hearsay - to inform their thinking and decisions.

“So the KPMG report did a great job highlighting growth and perspectives. That has now been updated, and it publicises some superb statistics about UK rail and what is does for the country.

“In my view, we shouldn’t really spend our time in narrow debates about, for example, whether we should have state bidders for franchises. There are much bigger challenges for the railway in the next 20 years, and that’s really where politicians should be focusing.

“Where do we want our railway to be in 20 years? Can we meet our growth aspirations? What does that mean for capacity? What does that mean for our rolling stock strategy? Frankly, compared with those really massive issues, whether or not we have a small state-owned entity bidding for franchises isn’t relevant (in my view) to finding answers to these much more fundamental challenges. Yes, they are certainly opportunities, but they are also challenges which we need to rise to.”

Well, he would say that, wouldn’t he? But Griffiths’ argument is underpinned with a logical and coherent argument.

As a private sector player, he is used to risk. And he knows a franchise bid can cost up to £10 million with a one-in-four/five chance of winning. Provided the playing field is level, he’ll take losses on the chin - but he believes that a state bidder tilts the playing field and exposes the taxpayer to risks and costs that rail privatisation was supposed to pass elsewhere.

I also venture the view that the West Coast franchise farce pushes you towards the view that the state just wouldn’t be that good at franchise bidding? This clearly strikes a resonant chord.

“That’s an interesting comment,” he says with a wry smile. “I’m just about old enough to remember that Transport for London did precisely this when the bus companies were privatised. It decided that, even though it had all the contestability and bidding in the bus market it needed, it would keep an operator. So, a state-owned operator placed bids for contracts, but it lasted only about 18 months before being abandoned - they didn’t win anything, and couldn’t justify themselves in the market relative to the private sector. So I just think for me, it’s a route that we just don’t need to go down - and I very much hope we don’t.”

His view is that, notwithstanding the West Coast collapse, we have a model that works, and that now the franchise procurement procedures have been so robustly fixed by Interim Franchising Director Pete Wilkinson (now Director of Franchised Passenger Services), we should get moving with confidence.

The interregnum caused by the West Coast collapse has cost at least two years, and we have seen no fewer than seven Direct Awards - effectively extensions of existing franchises. These have secured improvements for passengers and kept the ship afloat, but the franchising behemoth that was becalmed by West Coast really needs to start rolling again with confidence, he says. RDG and its members will continue to lobby and inform governments (whoever is in power, he says), and they will deal with whatever regime emerges.

“That’s the way the world is,” he shrugs.

Privateer fat cats

On that subject, how does he intend to deal with the public perception (fuelled relentlessly by the unions, in pursuit of their state ownership agenda) that the industry is run by uncaring, arrogant privateer fat cats who make excessive profits from rip-off fares and put absolutely nothing back?

“You’re right, we really are up against it here,” he acknowledges. “We have to keep communicating the positive story about what the industry is actually delivering. To the average man on the street, the real misconception - which is just wrong - is of high fares, high profits, and greedy capitalists…

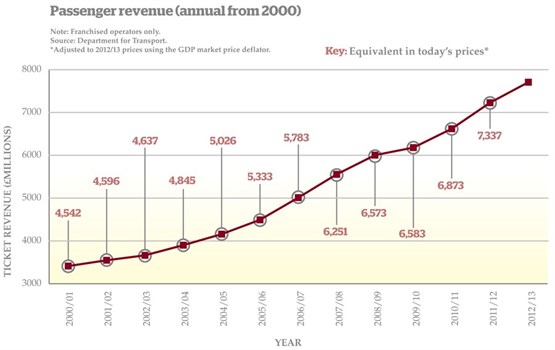

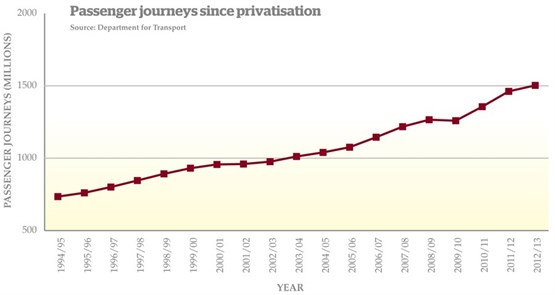

“Actually it isn’t like that at all. There has been £3.5 billion of additional revenue in UK rail since 1986/87, and 94% of that growth has come from increased passenger volume. A very small amount has come from fares.

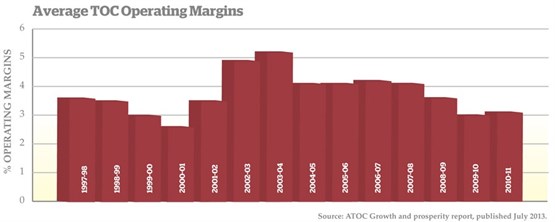

“Profits (and we do need to make profits, actually!) over the last few years have gone up 2%-3%, and in real terms profits are less today than what they were in 1986/87. And to be honest, I don’t think we make enough profit for the risk management time that we put in.”

Stagecoach is known for its very tough financial philosophy and approach. If that’s true and you’re unhappy with the margins, why is the company still here in railways?

“Because I still think from a shareholder point of view it’s a good industry, and now with the right structure, and so we can make a sensible return despite it being a very different business from the bus business.”

So relatively low returns are OK because they are stable over a long period?

“Yes, it’s steady. And in absolute terms it’s still a decent number, which justifies the management time we put into it.”

We return to fares, because Griffiths is clearly sore at what he believes are wrong impressions about TOCs. And he’s bullish on justifying some First Class fares.

“Yes - some fares relatively have gone up, but there are also plenty of great discounted fares now. But here’s another argument. The Germans and French have subsidised their First Class and business fares for years and years - but I believe that we shouldn’t do that.

“If a businessman wants to walk up ‘on the day’ to travel and go First Class on my train to Manchester, and it costs him £370 - so what? We shouldn’t subsidise that. If a well-heeled businessman wants to pay high fares for on-the-day travel, then we should not have a problem with that.

“What’s important is that with a bit of forward planning and thinking, if someone wants to go off-peak or plans their journey well, they can get a huge discount. That’s the model I aspire to, and I have no problem with that.”

But what if this means a creeping threat, and the eventual end of the affordable walk-on railway?

“I don’t think that will happen.”

I recall an early morning CrossCountry peak trip from York to Derby on a Friday - standing all the way on an overcrowded train, with multiple en route reservations of seats. It was a horrible journey.

“Certainly, there are challenges around capacity,” he agrees. “I accept that, and we are a victim of our own success in that sense. So how do we make the railway fit for the growth that is going to come over the next 20/30 years?

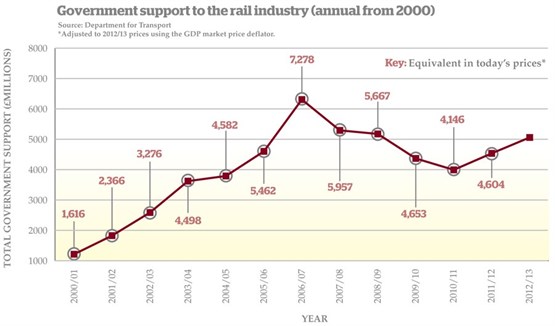

“But go back to the man on the street, which is the challenge. Ten or so years ago the Labour government made the call to change the funding of the railway, and it was probably the right call.”

I passionately disagree that going from a 50/50 share with the taxpayer to 75/25 was most certainly not ‘the right call’, with its inherent implication that those who do not use trains derive no benefit from the railway. That is arrant nonsense.

“Well, it’s been successful in the sense of changing the financial economics of the funding of the railway,” counters Griffiths. “But I do take your point regarding some individual passenger journeys. But while that was what they set out to do, we could reverse that tomorrow, Nigel!”

50/50 fares split

Really? Would RDG oppose Government policy, and campaign on that to go back to the 50/50 fares split with the taxpayer?

“You do build sustainable transport businesses on low fares.”

So that’s a yes, then?

“Absolutely! Yes, it’s a ‘yes’ - although it comes with a ‘but’ too,” he says. “And the but is this: if you take the Stagecoach business model over a long, long period, it’s all about volume, low fares, more demand, investment.

“The challenge we have is if fares come down in real terms, which we all want to see, then what does that mean for funding? Then there’s the capacity question. We have a fixed amount of capacity, and if we drive further volume growth - which you would hope you would get with lower fares - we would increase overcrowding. That can make the passenger experience even more difficult.”

But surely all the angst we’ve gone through over the past 20 years will have been pointless if all we do is price people off the railway?

“I don’t think we are pricing people off,” he comes back quickly. “We are not pricing people off because we are still getting phenomenal growth - but at some point we have to meet that growth with new capacity.

“Take South West Trains. I am hugely excited about the potential opportunity to increase Waterloo capacity by about 30%, but I need to persuade government to do it. I need to persuade government that there is a business case to go and do it. I’m working on it, and it’s the kind of challenge that we have to deal with.”

Griffiths is sanguine about the decision that was taken to move to 75/25 in ticket support - and points out that in the South East this means that 80% of the railway is now funded by the customer, not the taxpayer.

“That’s been a huge shift,” he says.

Two-tier Britain

But what about the North of England? They’ve all the fare increases but none of the new trains, and a small fraction of the infrastructure investment we’ve seen in the South? Are we heading for a two-tier Britain? And is he happy with that?

“I agree - we don’t want a two-tier. Equally, I’ve always again been very honest that London is the economic heart of the country, and our challenges around rolling stock and infrastructure are significant because we are running around a Victorian railway a lot, and that’s not sustainable either.

“But let’s stick with fares a moment. Existing contracts can be changed and new contracts can certainly be made on a basis of lower fares, but it gives us a big funding challenge, and that’s where politicians can’t pick and choose. You’ve got to look at this holistically, you’ve got to look at fares, you’ve got to look at demand, you’ve got to look at capacity, and we have to make sure the railway is sufficiently joined up.”

I press him harder on the idea of campaigning hard for things that the Government doesn’t like and will not welcome. In conversations with key senior executives, I pick up a lot of disenchantment, opposition and even anger about how Northern is being handled. All of them regard the DfT as wrong, and wrong-headed about the North - but dare not say so for fear of ‘biting the hand that feeds’. Will RDG campaign with equal vigour on matters that the DfT will not like (such as this), where there’s a common view that managers dare not speak publicly about? Surely this is the acid test for RDG?

“RDG isn’t going to shy away from difficult discussions with government about north-south funding, or pricing - we are very much up for those discussions. Government will ultimately be receptive or not to some of those things.”

Forgive how I put this, but will RDG have the balls to make the case, when that case is not welcomed by the DfT?

“Yes, if the case is right we WILL make that case.”

So, to sum up, you are going to be a CBI that’s totally supportive of the Government when it does the right thing, but a total thorn in their side if you believe it’s not?

“RDG is very focused on doing the right thing for the industry in the long term, and if that means there are some difficulties to be had with Government then we will not avoid those difficulties,” he says.

Does he believe that the new franchises such as Essex Thameside really do represent genuine transfer of non-GDP risk to the private sector? It was surely the case before that no such risk transfer was apparent? This prompts a frown.

“No, I don’t like saying that because I think there WAS absolute risk transfer from Day One of privatisation. We’ve had different models, and I really do think that over the last ten years the cap and collar revenue support model hasn’t been good for government or private operator.

“We need to move on from that, I agree - but there has definitely been proper risk transfer. If you look at these big revenue bids now, you have to think very, very hard about an eight- to ten-year contract in terms of what cost risk you’re assuming and what revenue risk you’re going to take. You then have to back it up with a lot of capital, and this goes back to my point about how a state bidder could do this.

“Take East Coast, for example. Dependent on the bids, you could be at risk for £150m-£200m of capital if it was to go wrong. No, we don’t want the market to fail, but that’s not to say we don’t expect the market to fail from time to time - because if it doesn’t fail, then it’s not a market!

“I think we have reset the equilibrium now, and the contracts are much better for both sides,” he explains.

“Government will get a better price and so should take macro-economic risk on these types of railways, and so should incentivise the private sector and hold it accountable for what it bids - but don’t hold us accountable for what happens in the economy, or GDP or central employment, over which we have no influence. Government is much better to sit with that risk - but everything else in the franchise? Yes, absolutely, the private sector should bear that risk.”

So where do you want RDG to be in two years… in five years? How do you want it to be seen? What do you want the impression to be when you mention its name in conversation?

“I hope it will be associated with leadership of the industry - that’s what we set out to do and I think we can do that,” he says.

“I think we are now starting to do that. But it has to be a partnership. We cannot lead without taking account of where Government is - its priorities, its challenges…. we have to be able to work with and respond to where they are at any point in time. And the DfT is looking for us to come up with solutions - they are crying out for us to take the industry forward.”

That requires trust though, doesn’t it?

“Yes, it does - but I think that trust has been rebuilt.”

And how will RDG work with the DfT’s new rail directorate - because that’s supposed to be, again, a similar leadership organisation?

Working together

“I think that will be the conduit to make sure that we are working together. And ‘together’ is the key. We can lead - but only in partnership with the DfT,” Griffiths explains.

“We are never going to shoulder the ultimate decision-making because railways are too important politically. The Secretary of State ultimately is always going to say: ‘I’m accountable, it’s my job,’ so the buck stops there.

“When you drag all the decisions back into the middle of the department, which is what I think has happened over a long period of time, it isn’t as successful because you need specialist knowledge.

“If you asked everybody around the RDG table, I bet they would all say they wanted a separate agency. Our worry was that we didn’t want that separate agency to take ages to come, which would mean yet further delay in getting franchising re-established. As matters stand, the Department seems to have been able to keep going with its programme, while also putting in place the building blocks for a separate agency.”

In Griffiths’ view, abolition of the Strategic Rail Authority and absorption of its role into the DfT was a major mistake, and that while political sensitivities mean Government will also be heavily involved, much more of an arm’s length feel to rail management is needed.

He is of the view that the West Coast meltdown made even the DfT agree with this, having had its fingers burned so badly. He looks back now and is clearly frustrated at how difficult Government and industry have made things for each other in running the railways and planning their growing future.

“God knows how many times somebody has announced that we are going to have a rail review, or we are to tinker with this or do that. None of that helps. You want stability in any industry, you want the right policy, the right regulation. And if you have the right structure then you can go forward.”

So is that RDG’s job?

“Absolutely. We need to work to try and give the industry that stability, to capitalise on all the positive things that it has done over the last 20 years. Then figure how we can repeat that - and more - going forward.”

And with that we part company. A couple of weeks later I dine as planned with Griffiths, Roberts and Watson in an enjoyable and clear demonstration of peace and harmony between RSG and RDG. They clearly do ‘get on’ and obviously are working together in the name of good all round. That‘s reassuring to see.

But you cannot airbrush history: RSG was born from the fury of the suppliers at being left out of RDG, and its midwife was (as I see it) a DfT which made very clear to RDG that it wanted the supply chain involved, and that they’d jolly well better go and find a way to make this happen if they wanted a balanced and constructive dialogue. I certainly did not imagine the supply chain fury at their exclusion from RDG, all of which suddenly evaporated with the formation of RSG and the embracing thereof by RDG.

In due course, it’s blindingly obvious that RSG and RDG should become RDSG, and maybe this will happen first in day to day work, and then more formally with a merger of the organisations themselves. Frankly, as long as the big constructive conversation takes place, it doesn’t concern me overmuch. It’s the outcome that matters. I wish them all well.

Certainly, Griffiths and Watson are a highly impressive pair, and Alstom and Stagecoach are to be congratulated for proving the naysayers wrong and allowing their expensive top executives to work for a wider industrial benefit and not narrow strictly shareholder interests. Long may that continue - and spread as a principle to other companies.

RDG has therefore made great strides, but its output remains patchy and inconsistent. Ironically, it is at its best when not much is happening and it tackles the long overdue educational aspect of PR that the industry has woefully neglected to its very great cost.

I hope it develops this aspect of its operations significantly and rapidly. This was clearly understood by the public relations departments of the pre-war ‘Big Four’ companies of the last private railway era, and it is a skill we need to re-embrace quickly and deeply. It could play a key role in drawing the sting from frequently critical media coverage.

And while I absolutely believe the gutsy Griffiths when he says he has the cojones to take on Government when necessary, the organisation beneath him needs to catch up and do likewise.

Fare increases

As this new journal prepared for press, the Government capped fare increases at RPI rather than RPI+1%, and new Rail Minister Claire Perry played to the crowd and cosied up to Labour traditionalists in a predictable and rather boring statement that South Eastern commuters deserved the much better deal she was “determined” to provide, and that the evil of overcrowding should end and that TOCs would be made to do better. We’ve heard all this playing to the gallery before.

And what did RDG say in its press release?

It “welcomed” the “good news” for passengers on fares, but failed to hammer home that the higher increase the Government had scrapped was its own policy, not that of the TOCs. The press release failed to mention the Government’s abolition of the flex mechanism that TOCs had so cynically abused over the past few years, and likewise steered clear of pointing out that overcrowding was a direct result of strict Government control of how many carriages the TOCs can have.

It would seem there’s still some way to go before RDG really does come across as a fearless CBI-style body. But let’s not to be too chippy… it’s early days yet, and Griffiths has only been in the post a half year or so. He’s making progress - slowly.

Change always comes too slowly, however, usually when it’s most needed. Griffiths must keep the pressure on and make sure that the changes he’s driving continue to come steadily, if not rapidly.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.