Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Read the peer reviews for this feature.

Download the graphs for this feature.

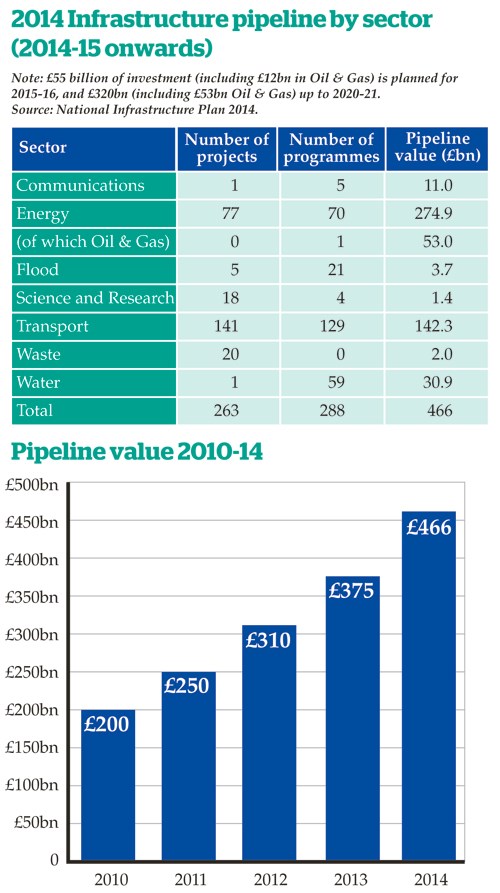

The first National Infrastructure Plan (NIP) was published in October 2010, setting out projects costing £200 billion over five years in energy, transport, digital communications, flood management, water and waste, and intellectual capital.

It specified a “new hierarchy for infrastructure investment, prioritising the maintenance and smarter use of assets, followed by targeted action to tackle network stress points and network development and, finally, delivering transformational, large-scale projects that are part of a clear, long-term strategy”. This article focuses on the rail component and looks at its relation to other modes.

The rail projects listed ranged from HS2 and Crossrail to the new southern entrance to Leeds station and resignalling schemes for Newport and Cardiff. Inevitably, the rail project list changes only slightly between reports, given the long planning and construction times associated with major projects. However, each report provides an update on progress.

The Government’s process for planning investment in the railway is enshrined in the Railways Act 2005. Every five years, starting with the High Level Output Specification (HLOS) of 2007, the Secretary of State for Transport publishes a statement in which he or she specifies the outputs they want to buy from the railways and the funds to be made available (the SoFA) to fund these outputs.

The HLOS sets out specimen schemes, many drawn from Network Rail’s Initial Industry Plan, which have the capability of delivering the specified outputs within the funding provided. The Office of Rail and Road has the role of verifying this before Network Rail is committed (through the Periodic Review of access charges) to delivering these outputs - these include specified levels of performance, safety and crowding, various projects such as electrification, and meeting efficiency and funding targets.

By the 2011 NIP, the cost of more than 500 projects set out in “a pipeline” had risen to over £250bn, with two-thirds of them to be privately funded in 2011-15. Some may have raised eyebrows when they saw in the March 2012 update the inclusion as a separate item of the Southern franchise agreement with Bombardier for 130 new carriages - the first item of rolling stock investment to appear in the NIP, but not normally classified as infrastructure.

The increase in the average annual infrastructure investment had risen to £33bn for 2010-12 from the £29bn average for 2005-10, driven by increased spend in the energy and transport sectors.

The 2012 ‘pipeline’ contained 550 projects valued at about £310bn, including £320 million for the Northern Hub, a ring-fenced £200m in the HLOS for the Strategic Freight Network, and a new line approaching Heathrow from Slough. The largest announcement was the July 2012 £4.5bn contract between the Department for Transport and Agility Trains for 596 IEP trains and maintenance depots.

The March 2013 update reported the decision to extend electrification beyond Cardiff to Swansea and to include the Valleys network. By the 2013 NIP, the annual average spend had risen to £45bn with a total value up to £375bn, and for the first time the NIP set out the specific rationale for each of the top 40 priority investments. These included the benefits that would accrue from HS2, line capacity improvements and electrification schemes.

The 2013 NIP also made mention for the first time of the regulatory framework for the development and testing of driverless cars. It also recognised that transport and energy had the lion’s share of the plan (schemes in those sectors accounted for £340bn of the £375bn total).

Completed projects

Performance targets also found their way into the 2013 NIP, with a Public Performance Measure target for 2019 of 92.5% of trains arriving on time, and a maximum of 2.2% of trains cancelled or arriving 30 minutes later than advertised.

Another introduction to the 2013 NIP was a changed methodology of measuring improvements in efficiency. From a baseline of 100 in 2005, changes in performance were calculated using a range of inputs such as service quality and reliability, asset condition, efficiency and safety (increased scores are improvements). The only drop related to overcrowding (a high-class problem, as former EWS chief Ed Burkhardt might have said), while some measures recorded dramatic improvements. Asset condition rose to 221, and train frequency to 157.

By 2014, the NIP could record completion of the new concourse at King’s Cross refurbishment as well as more than 400 other station improvements, 90% of tunnelling on Crossrail completed, and Royal Assent for the High Speed Rail Preparation Act. New announcements included a new station at Chesterton (near Cambridge), examination of alternative routes to the vulnerable section of railway through Dawlish, and support for the recommendations of the ‘Norwich in 90’ task force.

NIP 14 also set out the Government’s longer-term approach to infrastructure, with a 2018 completion date for Phase 1 of Crossrail, backing for HS3, and recognition of the need for greater co-ordination between HS2 and NR’s network improvements. Various short electrification schemes for CP6 (2019-24) were listed as being under consideration, such as Leeds-Harrogate-York and Sheffield-Doncaster.

Some projected milestones of the early reports now look optimistic. In 2011, it was confidently expected that electric services would operate to Bristol, Oxford and Newbury in 2016 and to Cardiff in 2017. The dates for the predominantly civil engineering Reading upgrade and King’s Cross station improvements were met, but schemes involving masts and wires look very different.

By the 2014 NIP, no date was given in future delivery milestones for any of the current electrification schemes apart from the start of Crossrail services in 2018.

The skills requirements for the DfT’s Damascene conversion to electrification in 2008-09 were grossly underestimated - and lack of human resources are now being blamed for slipping schedules. This seems surprising, given that the dearth of suitable skills should have been obvious - almost no electrification schemes had been carried out since 1986 and warnings had been made after completion of the East Coast Main Line wiring about the potential loss of skills in the industry unless the Government devised a rolling programme of electrification. They were ignored by the Thatcher government of the day.

The opening in autumn 2015 of the National Training Academy for Rail in Northampton will help to address the shortfall, but clearly the numbers of trainees on NR’s engineering apprenticeship programme, which began in 2005, have not been enough. Looking further ahead, the National College for High Speed Rail, divided between Doncaster and Birmingham, should also improve training numbers. Just as well given that the average age of engineers is currently 55 and 55,000 retirements are in prospect.

Len Porter, former chief executive of the Rail Safety and Standards Board, believes that civil engineering imperatives caused by ageing structures and a continued inadequate understanding of their physical condition will continue to distract NR from NIP upgrades.

Coupled with more extreme weather, landslips such as those at Tebay, New Cumnock, Tulloch and Harbury will become more common and require costly interventions to maintain resilience. The sea wall at Dawlish is naturally an extreme example, but based on previous climate-change models it had not been expected to become a serious problem until mid-century!

The National Policy Statement for National Networks (NPS), published in December 2014, recognised that work to tackle congestion will have to be augmented by measures to adapt to climate change and extreme weather events.

Building information modelling

Porter believes it is vital for NR to follow HS2’s lead in adopting Building Information Modelling requirements so as to gain a clear view of maintenance requirements, citing examples of problems through poor knowledge even of drainage channels. Equally, there is a perception that money is wasted in replacing assets that could have been improved or should have been kept in good order by effective low-cost maintenance.

Better asset knowledge and management reduces costs.

CP5 did set out requirements for modern asset management systems, which will be in place in CP6. Says Porter: “You can’t take cost out and improve performance if you don’t have the asset data and information management systems to populate the risk model.”

However, the Council for Science and Technology (CST) report on A National Infrastructure for the 21st Century observes “market-driven and efficiency-led approaches may not place sufficient value on resilience”.

Back in 2010, in the first paragraph of the first National Infrastructure Plan, it was recognised that the different infrastructure strands should not be treated in isolation. “Ensuring these networks are integrated and resilient is vital,” it advocated.

Yet since the Prescott era at the DfT, the word ‘integration’ has seldom been heard (although it makes a welcome reappearance in the NPS).

For decades, the Swiss have demonstrated with admirable intelligence and thoroughness that the only way to reduce car use is by dovetailing all the elements of non-car journeys - on foot, bicycle, bus, tram and train. Significant improvements have been made in Britain to ease the transition between modes, but we are still a long way from it being axiomatic that the railway station should be the destination of good cycle paths and served by most bus routes - naturally made much more difficult to achieve by bus deregulation.

Where NIPs do cite examples of “systemic linkages”, they are usually in terms of such obvious and uncontroversial synergies as using the Channel Tunnel to lay an electrical interconnector to the Continent.

Much more challenging from a planning point of view are the trade-offs between infrastructure and areas such as health and education. We know that air pollution contributes to around 30,000 deaths a year, with an estimated cost to Britain of £20bn. We know that diesel engines emit four times the nitrogen dioxide and 22 times the number of particulates as petrol equivalents. We know that children who have walked or cycled to school perform better than those who didn’t, and that childhood levels of obesity are a time bomb for the NHS.

Attempts to assess the cost benefits behind reducing the burden on the NHS - as a result of having a healthier, less obese population have been made by The Transport Appraisal and Strategic Modelling Division of the DfT. Maddison, Pearce et al in The True Costs of Road Pollution put the cost of air pollution from road transport at £19.7 billion. Yet we make only hesitant steps to effect significant change.

Modal change was cited in the first NIP as an object of a high-speed network, which “would make rail increasingly the mode of choice for inter-city journeys” and encourage “a large proportion of domestic airline travel on these routes to the train”.

No corresponding target has ever been set for urban journeys. In the case of London, abolition of the Western Extension charging zone in 2010 by Mayor Boris Johnson turned the clock back, and contributed to the city breaching EU pollution limits on 36 occasions by April 20 the following year.

Air quality plans

Five years later and on April 29 2015 the Supreme Court ruled that the Government had failed “to secure compliance in certain zones with the limits for nitrogen dioxide levels set by European Union law”, and ordered the Government to submit new air quality plans to the European Commission no later than December 31 2015. This relates to 38 out of 43 air-quality monitoring zones across Britain where limits are breached. Analysis by King’s College London ranks Oxford Street as one of the most heavily polluted streets on Earth for nitrogen dioxide.

Moreover, in May 2015 the Airports Commission unexpectedly re-opened its public consultation on expanding airport capacity in the South East, to focus on air quality. There is little doubt that air quality will play a greater part in prioritising transport investment - the difficulty comes in factoring it into the Government’s commitment to prioritise “capital spending on transport projects which can offer high economic returns when compared to investment projects in other sectors”.

The recent NPS acknowledges that rail freight produces 70% less CO2 than road freight, up to 15 times lower nitrous oxide emissions, and almost 90% lower PM10 emissions, while each freight train (depending on its load) can remove between 43 and 77 HGVs from the road. Yet no action is taken to complement the NIP projects by addressing the subsidies that are effectively given to road freight through paying for less than half the costs it imposes (RailReview Q4-2014). The Government has shied away from the lorry road user charging schemes operated in Germany, Switzerland and other European countries.

However, the large amount of space in the NPS devoted to the benefits of and “compelling need” for a network of strategic rail freight interchanges (SRFIs) suggests that they might make an appearance in future NIP pipelines.

Currently the third phase of Daventry International Rail Freight Terminal is the only terminal scheme. A higher priority for SRFIs would reflect the predicted changes in rail freight, which has experienced a slow decline in solid fuels over the 2011-13 time frame, but a 12% compound annual growth in domestic intermodal traffic and 5% intermodal traffic with ports.

The latest NIP purports to address the need for a long-term plan, and to counter previous “fragmented and reactive” developments. The first report stated that projects would be “part of a clear, long-term strategy”.

The performance measurements since 2013 did introduce categories that would be part of an overarching policy, but what the NIP does not provide (and arguably it is outside its remit) is a clear sense of direction that would allow it to escape accusations of continuing “fragmented and reactive” developments.

The exceptional lead times for the largest projects makes it very hard to anticipate what the world of transport will look like when they open - HS2 in 2026 and 2033, for example.

And the anticipated reduction in the demand for travel as a result of developments in IT, teleconferencing and email never occurred - quite the contrary, in fact. In much the same way as climate change is accelerating the urgency of civil engineering works to maintain resilience, so technical progress is condensing societal changes into much shorter time frames.

When the 2009 Council for Science and Technology report on A National Infrastructure for the 21st Century called for a vision that looked forward to 2050, it was blissfully unaware of the impact that some “disruptive technologies” would have on transport in just six years. In Britain, Uber may be upsetting black-cab drivers more than urban rail balance sheets, but in France, car sharing through BlaBlaCar is eroding SNCF’s long-distance traffic. This highlights the difficulty of forecasting transport developments and requirements ten years hence, let alone 35.

The only part of the UK planning strategically across all infrastructure to 2050 is London. Already the third most densely populated European country, and with recurrent annual net immigration totals of over 300,000, the UK needs to be able to identify where the extra five and a half to six million extra households (by 2031) are going to go, and what must be provided to make that possible. The Armitt Review of 2013 voiced a similar concern - “that successive governments have failed to set strategic priorities for infrastructure based on clear projections of future needs”.

Devolution of powers may make it more difficult to obtain the nationwide support that major projects require. In a devolution of powers to a Northern Powerhouse, would its urban areas grow evenly, or would some flourish at the expense of others? Following the first post-election speech given by Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne on building the Northern Powerhouse, there was some resentment that Manchester was perceived as top dog.

As Tom Worsley, Visiting Fellow in Transport Policy at Leeds University, points out, we lack understanding of the economics of place, to help us anticipate where the spatial distribution of economic activity is going to be. Land-use planning is a primary driver of transport demand, so should we be putting in place policies to influence it?

There are innumerable instances of poor co-ordination to achieve desirable outcomes - car factories and monumental distribution centres built without rail connection, or the underestimation of long-term transport needs for the Docklands, which entailed rebuilding the Docklands Light Railway at higher cost than the original construction.

Devolved decision-making also increases the difficulty of balancing local and national interests. It would be hard to defend the decision to build the Cambridge Guided Busway instead of re-opening the St Ives branch, which could have provided a strategic route for trains to Stansted off the East Coast Main Line at Huntingdon. The £180m cost of construction (originally £64m), coupled with the £30m-200m reconstruction estimates of the currently closed busway, makes the rail option look a badly missed opportunity.

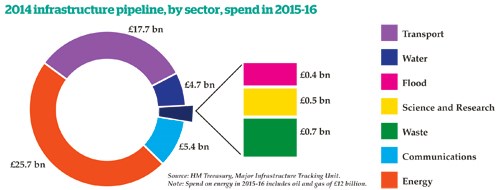

One can only applaud the Government’s levels of investment in the railway, albeit to make good decades of underinvestment that resulted in (for example) the proportion of electrified lines in Britain falling substantially below most other European countries. In the latest NIP, transport projects account for £142.3bn out of £466bn, exceeded only by energy (£274.9bn).

Electricity consumption

It’s energy supply that worries Len Porter. Transport is the largest single consumer of electricity and currently that is almost entirely used by Network Rail. At the very time that we have the largest electrification programme for decades (if not ever), there is the simultaneous prospect of the electric road vehicle becoming a significant user.

Since the Government relies on the private sector to provide energy, it generally keeps out of the planning of capacity. The independent regulator sets certain requirements as a condition of approving the prices charged to consumers, such as reliability of supplies, and leaves it to the generators to decide how to meet these requirements.

The success of the NIP will take decades to evaluate. If an overriding objective of transport policy is (as the NIP states) “to promote lower-carbon transport choices”, then that will be a fundamental measure. As will its impact on Britain’s low level of productivity, which the Policy Exchange report Delivering a 21st Century Infrastructure for Britain partly ascribes to weak infrastructure.

The National Policy Statement for National Networks forecast that by 2030 road traffic would increase by 30%, rail journeys by 40%, and rail freight by 100%.

One challenge that is never likely to disappear is how to resolve the currently irreconcilable objectives of improved services with a lower carbon footprint.

Peer review: Ian Prosser

Peer review: Ian Prosser

Director of Railway Safety, ORR

The article and the infrastructure report both highlight the extensive proposals to enhance the existing network, with transformational mega-projects such as Crossrail and High Speed 2.

It is very heartening for me to see the railway not just continuously improving its health and safety, but also developing and growing to take some big leaps into the 21st century through transformational projects - such as at King’s Cross, which is now completed.

However, while the railway gears up for enhancements, electrification and the large-scale projects, all of which are great news for the travelling public, I believe the critical issue is ensuring that the duty holders fully consider and secure ‘safety by design’ benefits at the very very early stages - in a complete and full sense, and not just bare minimum compliance with the requirements of the new Construction and Design Management (CDM) Regulations 2015.

I believe this will not only improve safety operation, such as in the case of stations safety design, it can also have a positive impact on cost reduction and the passenger experience.

This is not about “gold plating” - quite the reverse, in fact. This also includes the need to maintain the systems on an ongoing basis, as well as managing whole-life costs.

I am always struck by the example of the Shinkansen in Japan. This was designed as a complete system with safety uppermost in everyone’s mind right from the start, including managing future maintenance needs. So it has signalling systems that protect trains completely, enabling it to operate lightweight trains and minimise infrastructure and maintenance costs. The outcome is a railway that for 50 years has had a zero passenger fatality record (a performance that everyone else around the world aspires to) and high customer satisfaction and growth levels.

This has been achieved by looking at how the passenger is treated - from how they get to the station (including cross-model transport system integration) to how they are then treated in the station, to ensure not just safety, but also consistently great customer experience. Stations’ people flow and capacity are proactively optimised, minimising the number of platforms required, and hence capital costs. Key potential safety concerns, such as the platform train interface, are managed effectively.

In some of the industry projects, such as electrification, we as the regulator have seen a lack of ‘safety by design’ thinking at the very front end. Disappointingly, in some cases, it has been necessary for us to enforce, to try and ensure legal requirements have been met. Often these are at the basic, rather than the excellent level demonstrated by the likes of the Japanese.

So although it is very pleasing to see sustained strategic investment in Britain’s railways following decades of under-investment in areas such as electrification, it is very important that as an industry we make the very best of the opportunity to provide cost-effective developments that improve safety, efficiency and customer satisfaction. The way of achieving this is through ‘safety by design’.

Peer review: Malcolm Taylor

Peer review: Malcolm Taylor

Head of Technical Information, Crossrail

As an Engineer, the National Infrastructure Plans have

always made good reading for me. Several industry trends have emerged since the first plan in 2010, most notably the development of the Information Economy and the concepts for a digital Britain.

The strategic and political difficulties of choosing and planning major infrastructure were highlighted by the 2013 Armitt Review. Where the need for significant investment in infrastructure is identified, there will always be big planning and implementation issues to resolve. But once decided, we then have to ensure that what is wanted can be effectively delivered. That’s where the concepts of a digital-built Britain and BIM (Building Information Modelling) can help in improving efficiencies and reducing construction costs.

The Government Construction Strategy (2011) had a series of objectives, including the need to deliver a structured sector capability to “derive significant improvements in cost value and carbon performance through the use of open shareable asset information”. And so the world of BIM was born, which recognised the benefits to be gained from using advances on computer systems and developed new delivery processes to maximise those gains.

In the planning and design stages, the use of 3D BIM models help the owners and designers to work together and test them in the computer before they are built. In construction, the 3D models can be used for ensuring things fit together and are built in the right way. As construction moves into testing and commissioning, yet more BIM information is collected about the assets in data models. All of this information then gets used by the operators and maintainers.

The maintainers include more real-time information from remote condition monitoring sensors that tells them about how their assets are performing. The operator adds more real-time information about trains and passengers to tell them how their service is performing. So it’s all about information becoming a valuable resource, and treating it as such.

BIM has been identified as a significant contributor to the savings of £804 million in construction costs in 2013/14 that were recently announced by the Cabinet Office. It often seems to be thought of only as advanced 3D modelling, whereas the concepts actually apply to all types of information and data, and use information technology to redefine and optimise business processes. Key elements to BIM are creating a Common Data Environment (CDE) as a single source of truth for data (collecting only the data you need to collect - not whatever you can), and creating a

collaborative environment where you can share data between relevant parties.

It works. The emerging technologies and systems can indeed transform a construction project or engineering company from the inside out, but only if you make the effort to understand how it improves your project/business operating model, rather than just thinking of it as a change to some data management processes.

And it makes a difference - in Crossrail, we use 3D modelling extensively. But we also simplified our IT software applications by (for example) using workflows in a relational database for document management and contract administration. This eliminated the need for two expensive software applications and helped create (part of) our CDE for managing the project. This CDE will then be handed over to the future operator/maintainer.

Standing back for a moment - the more infrastructure we provide, the more we need to maintain. So when you consider that for typical infrastructure capital expenditure is often only 20%-40% of its whole life cost, it can be argued that it is more important to get value for money in operations and maintenance than in construction. The maintenance market in the UK is some £100 billion, so the more improvements we can make to this, the more money we will have to spend on new or replacement infrastructure.

So, where does the world of operations and maintenance fit in to the National Infrastructure Plan and the digital-built Britain BIM Level 3 Strategic Plan? It doesn’t - the emphasis is all on new build and construction.

We should be addressing this now. The reason? The whole life cost benefits of going digital and of working in a BIM environment are significant - they will reduce maintenance costs, freeing up money that is being soaked up by legacy systems and old-fashioned ways of working.

BIM concepts need to be pushed into the world of operations and maintenance with the same degree of vigour as they have been in design and construction, to generate these benefits.

Will this happen? Unlikely, as most BIM proponents are tucked up nicely working in consultancy and construction. So it will end up with the businesses needing to make this happen if it wants to.

No one has ever really defined what the BIM 2016 Government mandate really means in practice. But some of the signs are good: Network Rail is making significant progress towards creating a digital railway, but what that actually means in terms of asset management is yet to fully materialise. Transport for London’s rail businesses are seeking to rationalise their suite of separate asset management systems, and are looking at how the concepts of a CDE might work with the aim of realising the benefits of a single system.

Why is all of this important? Moving into the Information Economy with BIM processes, the digital railway describes a modern, best practice railway that uses integrated common data systems, real-time information systems and knowledge to enable everyone interested to make the best decisions possible in making it all work. From customers selecting a train and operators managing the service, through to programme teams and infrastructure managers selecting, installing and managing assets, and finance teams securing appropriate funding to renew assets, a digital railway provides real-time, actionable knowledge from a single shared source, to consistently inform decision-makers.

Traditionally, railways have used an analogue approach with multiple and disparate sources of data, often managed via paper-based or electronic representations of paper, with manual or unconnected electronic processes. This leads to duplication and divergence in data sets, onerous and inefficient management processes and ill-informed decision making, generally leading to waste and further costs.

Digital railways rely on advanced computing and data storage solutions, which are commonplace in today’s business environment. Modern technologies take advantage of information mobility and modelling simulations, using asset information intelligently to deliver a responsive and effective service.

If we look at the benefits achieved by other organisations through the use of more integrated data systems and a collaborative management process, we can offer evidence of significant benefits. For example, after a disastrous fire, SSB in Switzerland went digital and delivered a 20% reduction in unit maintenance costs, identification and repair of more than 50% of issues before they affected service, thereby reducing delays by 33 hours per month. McNulty (DfT, Realising the Potential of UK Rail) also cited Network Rail’s ORBIS programme, Scottish Power and Ausgrid as other organisations who have achieved or were proposing big savings in operational expenditure through improved data and information management.

Taking a fresh look at the way we currently tackle asset management systems and processes is not a comfortable or easy issue for asset managers, as it challenges many traditional practices and customs, yet it is absolutely necessary. Just because we’ve done things in the past with simple spreadsheets and 2D drawings does not mean that it’s the best way to do it now.

So the infrastructure world has a number of choices. Carry on constructing new projects as best we can and then maintain them in legacy systems? Start trying to understand the world of BIM Level 3? Or simply recognise there are significant cost benefits to improving the way we currently manage our existing infrastructure?

The highways sector has begun to recognise the maintenance benefits in using BIM technologies and processes, and it’s important we do so in rail. Investment in this area will ultimately help fund more renewals and new infrastructure itself, as well as delivering improved reliability and customer service.

Peer review: Philippa Edmunds

Peer review: Philippa Edmunds

Freight on Rail Manager, Campaign for Better Transport

Anthony Lambert makes cogent arguments for long-term strategic infrastructure planning and the need for integration across modes in government planning. I would like to discuss these themes further, through a freight lens.

Rail freight can be overlooked, even though the Rail Delivery Group showed that it is worth £1.6 billion per annum to the UK economy. Therefore, I believe that a National Freight Strategy could set a framework and inform the devolution debate.

The Government’s process for planning and funding invest-ment in the railways has allowed the rail freight industry to make the case for key infrastructure enhancements as part of the Strategic Rail Freight Network vision. The £545 million that the Government invested on the Strategic Rail Freight Network in 2009-2014 included key gauge upgrades on the port routes - rail’s market share out of Southampton port increased from 29% to 36% within a year of completion of the gauge upgrade, demonstrating that targeted rail freight upgrades work (Financial analysis: £70.7m project having a Net Present value of £376m).

During the current Control Period (2014-2019), in recognition of the importance of the economic, safety and environmental benefits of rail freight, £254m has been allocated to the Strategic Rail Freight Network for key capacity upgrades.

A series of key projects, including the much-needed capacity enhancements out of the ports of Felixstowe and Southampton, as well as Great Western gauge upgrades, are agreed priorities. However, due to a combination of projects running seriously over budget and a shortage of engineering expertise, there are serious delays. Consequently, some of these crucial works may not be carried out in this timescale, jeopardising the projects as funding is not automatically carried over into the next period.

These upgrades are needed to cater for the existing and forecasted growth. Consumer rail freight has grown by 30% since 2006/07, and is now almost a third of traffic and is forecast at 16% annual growth. Construction traffic grew by 17% in 2013/14 and maintained these high volumes last year, showing its potential to service this expanding sector.

By 2034, this consumer traffic will have quadrupled, providing existing market conditions are maintained and the terminals that are needed are built. More freight capacity is needed, as well as the ability to cater for longer, heavier and faster trains, and so Network Rail is undertaking commodity studies to try to strengthen protection of these strategic rail freight paths.

The strengthening of the case for Strategic Rail Freight Inter-changes in last December’s National Networks National Policy Statement was welcome, as forecasted volumes cannot be realised without more road/rail transfer points. These Strategic Rail Freight Interchanges, funded by the private sector, offer potential for considerable local and regional economic regeneration. The Daventry Strategic Rail Freight Interchange, where Tesco has a terminal, already employs 5,000 people - and this will increase to 9,000 when the latest expansion is completed.

The rail freight industry also needs long-term certainty, so the industry and its customers are pressing for track access charges to be set by the Office of Rail and Road for a ten-year period, rather than the current five-year period.

The new monitoring of Highways England by ORR is important, as there is a lack of integration of government planning and scrutiny across the different modes. The ORR must be able to compare rail and road costs, which is important because rail has to compete with road on price, even though there is not a level playing field.

Government figures show that HGVs receive a £6.5bn in subsidy each year (RailReview Q4-2014). What this means is that HGVs are paying less than a third of the very real costs they actually impose on society in terms of road congestion, collisions, road damage and pollution. It is therefore hard for rail to compete, as it receives ten times less subsidy than HGVs. If rail is to play its full role in the logistics industry, the Government needs to support rail freight accordingly.

This is where the Government missed an opportunity for a fairer lorry charging system, when it introduced the time-based system last year. A comprehensive distance-based lorry road user charging system could have charged HGVs for their actual impact on the network in terms of congestion, track costs and pollution, encouraging more efficient and sustainable use of HGVs as well as charging foreign lorries appropriately.

A growing number of countries have replaced their time-based systems with km-charging systems on motorways, including Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Portugal. This has increased efficiency in road transport through increased load factors and fewer empty trips, and decreased the average distance travelled per tonne. In Germany, four years after the Maut (toll) system was introduced in 2005, empty lorries were reduced by 11% - previously empty running had been at similar levels to the current 28% in the UK.

ORR’s new role could also improve cross-modal planning. A glaring fault in the Highways Agency road-based studies was that they did not take account of any of the parallel rail routes when analysing the corridors from either Southampton or Felixstowe to the West Midlands… even though rail handles almost a third of the freight traffic out of both ports. Without proper corridor analysis, there is a danger that the latest and planned upgrades to the Strategic Rail Freight Network will not be taken into account in Government planning, which could result in a false picture of demand on the strategic road network.

Freight on Rail will be pressing the Government to support key capital investments on the network in the Comprehensive Spending Review, so that rail freight can continue to offer a reliable competitive service that benefits the economy and society.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.