Why is HS2 ‘so expensive’, and is it being ‘gold-plated’? Mel Holley investigates.

In this article:

Why is HS2 ‘so expensive’, and is it being ‘gold-plated’? Mel Holley investigates.

In this article:

- HS2 acts as a modern railway bypass, relieving existing rail congestion and delivering long-term infrastructure upgrades.

- Though costly and controversial, HS2 brings extensive community, environmental and highway benefits across its construction route.

- Public objections and modern standards have driven costs, but the legacy includes better roads, safety upgrades and community funding.

What’s in it for me? That’s the war-cry of the modern generation… or is it?

Humans are strange creatures. They want to develop and improve, but only on their terms. They also like stability - in other words, they don’t like change.

Perhaps they live in a housing estate that was green fields until the 1960s. But now that expanded village seems ‘permanent’ and was ‘always there’. Until someone proposes building more houses on adjacent green fields. Then all hell breaks loose.

“How will the local primary school/doctors/road network cope with all the extra people/traffic?” villagers will cry.

Yet, in the not-so recent past, they may well have been campaigning for a bypass (which often leads to more development), or to ‘save’ the school threatened with closure due to falling pupil numbers, or bemoaning that the village’s shops are closing.

The answer is a Section 106 planning obligation - a legally binding quid pro quo that entails the developer paying for something extra in exchange for planning permission, such as a new bus service, improvements to the local road network, or creating a park.

Give it another 30 years, and residents in that new development will adopt the same thinking, and will likely be among those objecting to the next development.

And that’s before we get onto the cases of ‘newbies’ moving into an area and complaining about the sound of church bells.

Or, like the Severn Valley Railway, buying new-build houses overlooking its Bridgnorth workshops and then complaining about the noise - forcing the railway to build an expensive boiler shop, now that their adjacent green fields have been turned into housing.

French novelist Jean-Baptiste Alphonse (1808-90) coined a saying encompassing this: Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose: the more things change, the more they stay the same.

And so it is with HS2.

The arguments are now almost ancient history. People along the route looked at the proposals and called for stations to serve their communities, overlooking the point that a high-speed route is… just that.

Like the local bypasses those residents would have been calling for, HS2 provides relief for traffic. Railway professionals know that if you’re going to build a new railway, it’s obvious that it should be aligned to modern standards (straight) and built for speed.

“Upgrade the existing railway” was another argument. That’s already happened with the Chiltern Line and (as much as is possible) with the West Coast Main Line, which also demonstrated how ruinously expensive and disruptive such works are - as well as failing to deliver the hoped-for benefits.

Recent upgrades to the East Coast Main Line (at a cost of some £4 billion over the past decade) have also yet to realise the capacity benefits that were hoped for. Meanwhile, wrangles continue over which trains should have priority: non-stop expresses, regional links, local ‘stoppers’, or freight?

In reality, an ECML bypass would be a great idea. This has been proposed before - and indeed had the original HS2 plan come to fruition (the leg to Leeds), then this would have released significant capacity on the overloaded southern section of the ECML.

One aspect that has made HS2 more expensive (although it’s not clear exactly how much more) is the decision to engineer it for a higher top speed than other new-build high-speed railways.

This is for a different article, but it’s one of the key arguments that objectors continue to use against the project.

While HS2 makes sense as a name, it’s principally a bypass. When you build a bypass (in road terms) you do it to the latest standards and often future-proof it. This is cheaper in the long run - witness embankments at roundabouts for a future flyover to be added, ‘dead spurs’ for possible other roads, and sight lines on new roads, far in excess of their permitted speed.

But while ‘WCML bypass’ might be more accurate, it never sounded as good as ‘HS2’. And the failed 1997 WCML PUG2 (Passenger UpGrade 2) to deliver 140mph trains casts a long shadow.

Indeed, its failure ultimately led to the very logical HS2 proposal - to build a rail ‘bypass’ which unlocks capacity on the existing ‘classic’ lines, for commuter, regional and freight trains.

“What’s the point of all this, just so people can get to Birmingham a bit quicker?” has been the oft- and still-repeated chant of the anti-HS2 faction, with a slight sneer as to why anybody would even want to go to Birmingham.

But that’s not the point. If you build new, you build to current standards. This is one reason why HS2 is more expensive than at first blush.

Having said that, HS2 Ltd is clear that its current project review is needed, and that some decisions made previously have unnecessarily increased costs. The organisation is not in denial.

But if you think building railways is expensive, just look at the cost (and land take) of new road schemes.

‘Exhibit A’ is the replacement of 1.5 miles of single-carriageway A47 between the A1 and the Castor bypass (on the extreme edge of Peterborough) with a dual carriageway.

Designed pre-COVID, it has almost doubled in price and the now £100 million project will save motorists around five minutes on their morning commute. For this, properties will be demolished, businesses disrupted, and a huge scar put through the landscape.

There have been objections, and as a result of a 2017 consultation many changes have been made to the route (three options were provided originally), in a 2018 design review.

Britain is very democratic. And when it comes to planning, consultation and the ability to object is the name of the game. Before you even start talking about newts and bats, there is the opportunity to object and delay at almost every stage in a project.

Those who don’t want something will use this to the full. It all adds cost and time - as does every redesign after a consultation.

Hence the kickbacks (Section 106 grants). Or in the case of wind farms, other community benefits are provided as ‘sweeteners’.

Like building a new railway, a new road needs to be built to current standards. Bridges will be higher and wider than legacy ones, carriageway and pavements widths are standardised, and so on. It would, of course, be lunacy to build a new road to standards of the past.

HS2 interacts with many roads. And while ‘betterment’ of the local road network isn’t part of the plan, it is one of the many spin-off benefits.

An example is the Fosse Way, south-west of Leamington Spa. It has long been an accident blackspot, and over the years the worst of the crossroads on the Roman-aligned route have been modified. But not all, although Warwickshire County Council had installed additional signage at the worst junctions.

Now, HS2 is doing the job for it.

In one case, a simple crossroads (near where HS2 passes under the Fosse Way) has now become a complex roundabout. Partly to serve an HS2 worksite, it will leave a permanent legacy and benefit.

That will be the case all along the route, with the cost simply wrapped up as part of the civil engineering programme, so we can’t tease it out.

But look at non-HS2 road schemes, and you’ll discover that a ‘basic’ roundabout costs about £2m, and a simple ‘four-legger’ in the region of £4m-£6m. Add in other works, such as a culvert under the site, and it jumps again.

‘Exhibit B’ is the A16/A151 Springfield Roundabout in Spalding (Lincolnshire), opened after 14 months’ work in November 2024.

It cost £8.4m. But when you add in other works such as bridges, you’ll quickly hit £20m (or more). Like railways, road building is not cheap - and that’s before the recent massive price jumps in concrete (20%) and steel (70%) are taken into consideration.

HS2 is only empowered and funded to realign or divert roads on a like-for-like basis, rather than specifically delivering enhancements. However, with these works completed using modern design standards and construction specifications (often not the case for the lengths of the network they replace), there is a key legacy benefit.

Its highways programme is extensive. To help give an indication of scale, on the West Midlands to Warwickshire section of the route, delivered by contractor Balfour Beatty VINCI, there are:

65 new overbridges for highway/Public rights of way (PRoW).

75 new PRoW including bridleways.

More than 100 carriageway realignments/upgrades, including the provision of future-proofing the road network. These include improvements to traffic capacity and accessibility. Examples include the area around Interchange station (Solihull/NEC) and green overbridges, such as at Stoneleigh Road by the National Agricultural and Exhibition Centre (near Kenilworth).

Many of these schemes also include active travel (walking, cycling, horse-riding) provision - a further benefit.

On this section of the route, HS2 is delivering 40 road realignments and 25 new road bridges, leaving it better (in road terms) than before.

Route-wide, HS2 is building more than 500 bridging structures - including over 50 major viaducts. These will stretch for a combined total of nine miles across valleys, rivers, roads and flood plains.

Already, the A41 realignment in Aylesbury is in use. This provides a brand-new stretch of road to modern standards, in contrast to the older worn-out and damaged sections of road.

The A41 (main trunk road into Aylesbury from Bicester) had a notoriously bad junction - an accident black spot. Locally, there were concerns about the speed of vehicles and the risks of turning or crossing the carriageway.

The realignment re-routes the road slightly north of the original road, across an overbridge over HS2, with two new roundabouts that circumvent the junction and accident black spot.

It also incorporates two new roundabouts, enabling drivers using connecting side roads a safer means of joining the A41 without the need to undertake risky (especially at night) cross-carriageway manoeuvres.

Additionally, a new drainage system is designed to accommodate ‘high-intensity events’ factoring in climate change considerations. This will mean less pooling of water on the roads and minimise the risk of flooding.

It also provides a hardened verge for Buckinghamshire council for its maintenance activities.

The original HS2 proposal was similar to HS1 (Folkestone to St Pancras), with cuttings, viaducts and tunnels to traverse the landscape, and access to Euston via tunnels.

Widespread opposition, with strong political support from MPs (mainly in the Chilterns), saw more of HS2 put into tunnels. Not because tunnels were needed from an engineering point of view, but to satisfy objectors. Existing tunnels were lengthened (with shorter cuttings), and more Victorian ‘cut-and-cover’ tunnels added.

The story of Britain’s railways is littered with objections, and that legacy remains.

The reason that King’s Cross, St Pancras, Euston and Marylebone are all on the same alignment is that the Victorian city’s authorities refused permission for them to be south of the Euston Road.

Oxford and Cambridge have their railway stations some distance from the city centre, ‘outside the city walls’, after objections by the city.

As for tunnels, the country is littered with schemes that would have seen the railway in a cutting, had it not been for the landowner’s insistence that a tunnel must be built - or ‘no railway’.

Among the most well-known is the 710-metre Shugborough Tunnel on the WCML Trent Valley section. Running under part of the Shugborough Estate in Colwich (Staffordshire), it was built in 1846 with a castellated western portal, to hide the line at the insistence of landowner Thomas Anson, 1st Earl of Lichfield. Shugborough Tunnel is the largest engineering work on the line.

In total, more than 32 miles of HS2’s 140 miles will be in tunnels. The increase in tunnelling lengths after revisions is:

10.94 miles increase in twin bore Tunnel Boring Machine tunnels (40% more).

1.8 miles increase in twin-cell cut and cover tunnels (40% more).

0.34 miles in single-cell cut and cover tunnels (100% more).

Tunnelling is expensive - even if it’s a now notorious (and much derided) £100m bat tunnel.

In the meantime, construction continues between the West Midlands and London, with HS2 now supporting more than 31,000 jobs.

The positive legacy of HS2 will be around for many years - not only in training and employment (see panel), but also for local communities which benefit from £40m being spent on projects they choose.

Unsurprisingly, new community centres, playing fields, swimming pools and sports facilities head the list of £18.53m of funding so far awarded to 339 Community and Environment Fund (CEF) and Business and Local Economy Fund (BLEF) projects across the route. The full list can be viewed here: https://hs2funds.org.uk/home/projects-funded-by-hs2-funds/

The first grants were awarded in June 2017, and they continue to be made with funds still open for new applications. There are two classes of applications: grants up to £10,000 and those between £10,001 and £74,000.

While some will argue that £40m is a drop in the ocean compared with the total cost of HS2, for those arguing that every last penny should be cut back, who would be brave enough to call a halt to this?

Should that £21.47m that has yet to be awarded be clawed back? No one - not even the harshest critic - thinks so.

Originally the fund was £45m, but the cancellation of Phase 2a (West Midlands to Crewe) means that its £5m grant ‘pot’ has now been withdrawn. However, more than a dozen community projects on this section had already been approved, and most are now complete, despite Phase 2a never getting much further than a few site compounds.

Applications to the funds can be made by any organisation (such as a Scout group or cricket club), with parish councils among the principal applicants (see table).

It is all money that would never have been available, had it not been for HS2. There is much to be thankful for.

Case Study: HS2 green bridge, National Agricultural and Exhibition Centre

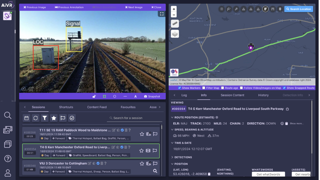

HS2’s green bridge at the National Agricultural and Exhibition Centre, near Kenilworth in Warwickshire, is one of 16 ‘green’ bridges on the project. It also deals with an accident blackspot and traffic congestion problem.

Main construction work is now complete on the Stoneleigh Road structure, which will comprise a dual carriageway and two nature corridors that will give safe passage for wildlife to cross the railway.

It is one of 16 similar green bridges on the HS2 project between London and the West Midlands.

Piling work on the bridge (33 metres long, 42 metres wide) started in October 2023, with 50 people employed at peak construction. The finishing touches are now being made, including installation of 32 parapets (nine tonnes each), following a huge pour of 1,900 cubic metres of concrete to create a deck slab in late 2024.

With the main construction work complete, engineers will begin realigning Stoneleigh Road over the top of the bridge and constructing a new roundabout linking the main entrance of Stoneleigh Business Park.

Hedgerows and vegetation will be planted in nine-metre strips either side of the realigned road to create safe corridors for birds, small animals and insects.

The realignment process and nature corridor landscaping is due for completion in autumn 2025, with traffic then beginning to flow over the bridge.

“What makes Stoneleigh Road bridge special is the addition of valuable green space either side, meaning wildlife can safely pass over the high-speed railway line” says HS2 Ltd Senior Project Manager Vicki Lee,

“Wherever possible, it’s important we integrate green measures and multifunctional design features, creating a railway that blends into the character of the surrounding landscape.”

Skills, education and employment

Like the London Olympics, HS2 will leave a legacy in more than just concrete and steel. It has invested heavily in upskilling, with a focus on creating meaningful employment opportunities for people close to the line of route.

HS2 Ltd has set up skills academies and training centres, with a focus on job types where there are national skills shortages such as tunnelling, piling operatives, and plant machinery operatives.

This investment provides skills for life and will enable people to transition into careers well beyond their time on HS2. The progress so far is very positive:

A commitment to create 2,000 apprenticeship opportunities throughout the lifespan of project. To date, 1,810 people have started an apprenticeship.

Actively strive to support unemployed back to work. HS2 academies have helped people to develop new skills as well as ongoing career and learning opportunities. To date, HS2 has supported 4,824 people who were out of work into new careers.

HS2 runs an annual graduate training scheme, welcoming university graduates every year on a two-year programme, where they rotate across the business to learn about all aspects of HS2’s delivery. So far, 117 people have joined HS2’s graduate training programme. 2025 recruitment opened on March 3, with 31 more placements this time around.

Many HS2 contractors offer summer placements to university students, giving them the opportunity to develop workplace experience. These paid roles have helped to give students a foot in the door and been a big success.

In the 2024 intake, placements were open to candidates studying a broad range of subjects, with opportunities in the following business areas: Civil Engineering (earthworks, tunnels and structures); Quantity Surveying; Design Engineering; Environment and Sustainable Delivery; Business support functions (procurement, IT and finance).

For a full version of this article with more images, Subscribe today and never miss an issue of RAIL. With a Print + Digital subscription, you’ll get each issue delivered to your door for FREE (UK only). Plus, enjoy an exclusive monthly e-newsletter from the Editor, rewards, discounts and prizes, AND full access to the latest and previous issues via the app.

Login to continue reading

Or register with RAIL to keep up-to-date with the latest news, insight and opinion.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.